Approaching source material as culturally significant and revered as Jennie Livingston’s seminal 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning seems like a crazy thing to do for your debut novel — but for 28-year-old Joseph Cassara it kind of happened by accident. “I didn’t think that I was writing a novel,” he says. “It was just a short story and some writing exercises that fused fictional characters with people from the actual documentary.”

Drawing particular inspiration from the House of Xtravaganza, the first house from the New York ballroom scene comprised of Latinx individuals, Joseph says that, as he continued to write, he realised he had an emotional and psychic connection to the still active group.

“I’m Puerto Rican and Italian and I grew up in New Jersey, so I wondered if I had been born 15 or 20 years earlier, whether that was the community I would have sought out when I felt angry,” he says. He describes how he felt robbed, as a young gay person, when a “generation of thinkers and intellectuals and artists” all died during the HIV/AIDs crisis. “When I watched Paris Is Burning, I saw them captured in their youth,” he continues. “I knew that they were no longer around, but I got to see them being free in their bodies and relating with each other and that really spoke to me.”

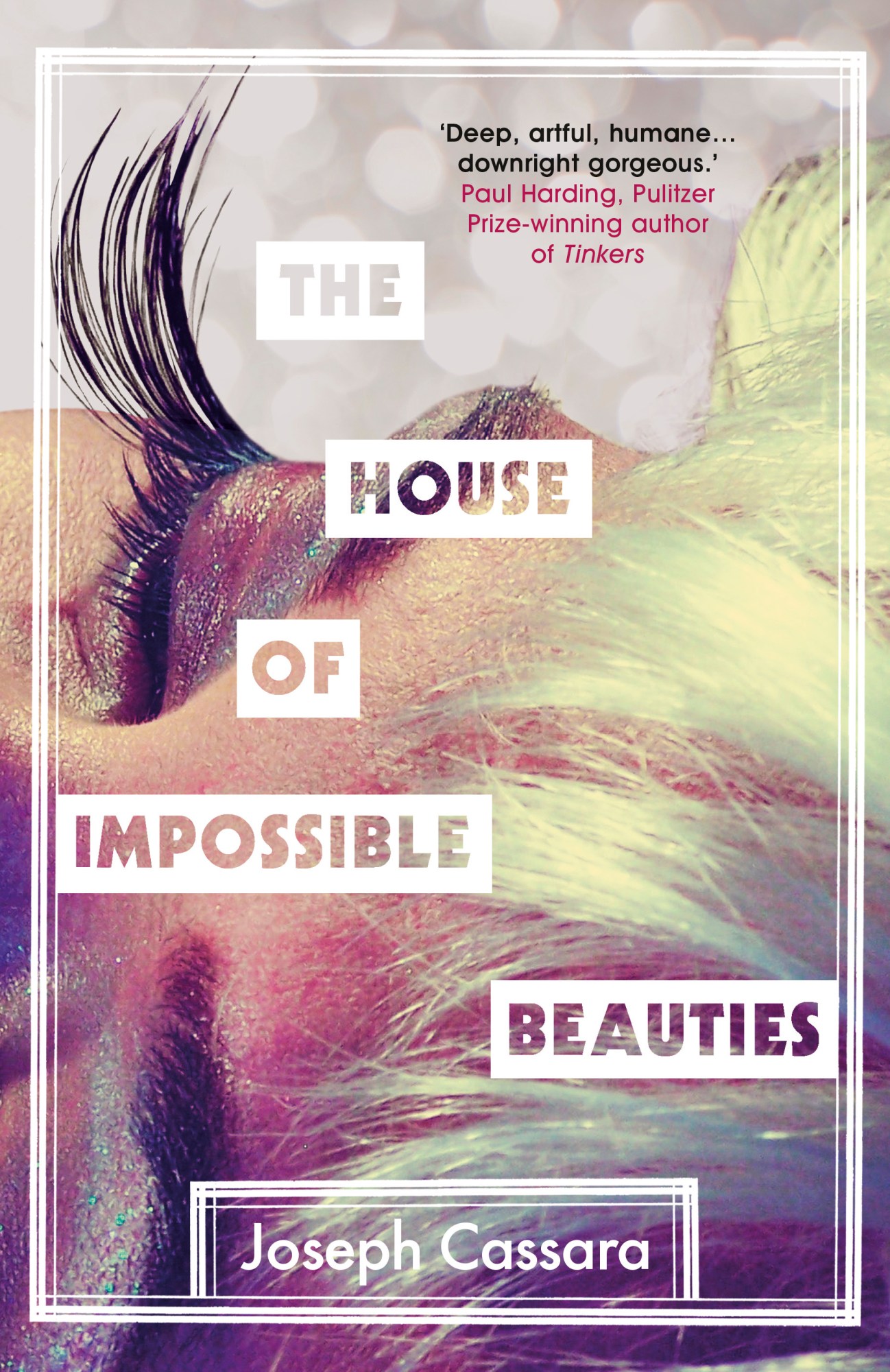

It’s this that sets the framework for Joseph’s novel The House of Impossible Beauties. The book, set during the 80s and early 90s, follows a fictionalised story of how Angel/Angie and Hector formed the House of Xtravaganza. The novel features a whole host of familiar characters, including drag queen Dorian Corey, who appears like a prophet to divulge wisdom, and transgender performer and aspiring model Venus, who joined the Xtravaganzas in 1983. A surprisingly domestic novel, we follow this proxy family as they navigate love, life and death. We caught up the author to talk about the complexities of bringing these characters back to life, gender identity and the role of the queer author.

When you were working on the novel, what kind of research did you do?

I created a folder on my laptop and I threw everything I could into it. There were a lot of images that I found, not just from the documentary but also from the time period. It was such a visual and colourful period, so I looked at what the Christopher Street Pier looked like, what the outfits looked like, what the subway and graffiti looked like.

Then there were also oral accounts of people telling their stories. There is a scene in the novel where Hector goes to [legendary nightclub] Paradise Garage, and in order to write that scene I had to read about what it was like to actually experience Paradise Garage. That’s where I learned, for example, that there was no bar where they sold drinks. There was just table with a punch bowl. It’s such a real detail, but imagine if I had written that scene and they’d gone and bought a G&T at a bar. So I had to incorporate these really small details, and then whenever I found gaps in history that’s when I’d have to use imagination to fill things in.

It must have been hard because that period and that social group aren’t very well documented.

There was so little information about Hector, for example. I knew when he was born, I knew when he died, and I knew that he was a very good dancer. So what I imagined was, what would this man who started this house, had dreams of being a dancer and was in love with Angie [Xtravaganza] look like if I were to put it into a narrative? His entire chapter where I imagined his past is all fictional, but my goal was for it to feel emotionally true. I was reminded of Ann Patchett’s quote, ‘None of this happened and all of it is true’.

The balls do feature in the novel, but there aren’t lots of scenes set in them. Why is that?

I didn’t want the reader to become numb to those details. I feel like the novel really is concerned with their inner lives, their relationships with each other and how they live at home. I was trying to draw upon the tropes of the American family novel — which is usually about white, upper-middle class families living in suburbia who are unhappy for whatever reason.

“[When writing] I was reminded of Ann Patchett’s quote, ‘None of this happened and all of it is true’.”

The novel approaches gender identity with such nuance and it isn’t how we would discuss gender now. Why did you present it in that way?

It would be totally anachronistic if I applied a 2018 lens to people who were living in the late 70s and early 80s. I hoped that there would be a shift across the novel from the beginning of where there’s focus on the body and genitalia and what it means to be trapped in a body that you don’t feel like belongs to you in terms of your gender identity. As the book unfolds, the focus changes as the characters mature. I also tried to focus on pronoun shifts, which happens more often at the beginning of the book. There’s the scene in the first chapter where Angel is arguing with her mother in the kitchen and she takes off her dress and puts on her boy drag and the pronoun shifts back to ‘he’. Then, when she’s talking to her brother Miguel, it shifts back to ‘she’. It was fun to play with the language and how that can indicate things to the reader about what is happening in the emotional terrain of the novel.

Being 28, you didn’t live through the HIV crisis. What was it like writing about it without that real life context?

I find the 80s and 90s to be this fascinating period because it’s still close enough in recent history where we feel a connection to it, even if we didn’t live through it, but it’s not far enough in the past to feel really distant. So I wonder whether the fact that I didn’t live through it gave me some kind of emotional distance. I had an older cousin who died in, I think, 1984 and he had HIV. He was closeted and the family refused to acknowledge that he had contracted the virus from another man. They said he got an infection from his orthodontic braces. They found a funeral home that would take his body and they wrapped it in a black plastic bag and hermetically sealed the coffin. Those details were on my mind as I was writing, but I wonder how I would have approached this novel if I had actually known that cousin and experienced his death.

One thing I’m really interested in is what role queer authors play in documenting queer pasts. Where do you stand on this?

I’m really interested in resurrecting the stories and bringing them back into the contemporary consciousness by imagining some of the gaps we have and turning them into a fictional narrative. I’m even doing that with my next novel. I’m just always angry when I read some stories and things seem to have been erased because people who document history have their own goals and their own biases. So, when I go back and I see things that aren’t there that should be there, my goal is — and I think queer writers and artists should do this — to use what we know about what it means to be queer today in a society that is not queer, and try to deeply imagine the holes that are there. That way we can spark a discussion in our community about these stories.

Joseph Cassara’s The House of Impossible Beauties is out now. You can catch him in conversation with Shon Faye, along with a screening of Paris is Burning, in London on 13 March. Tickets are available here .