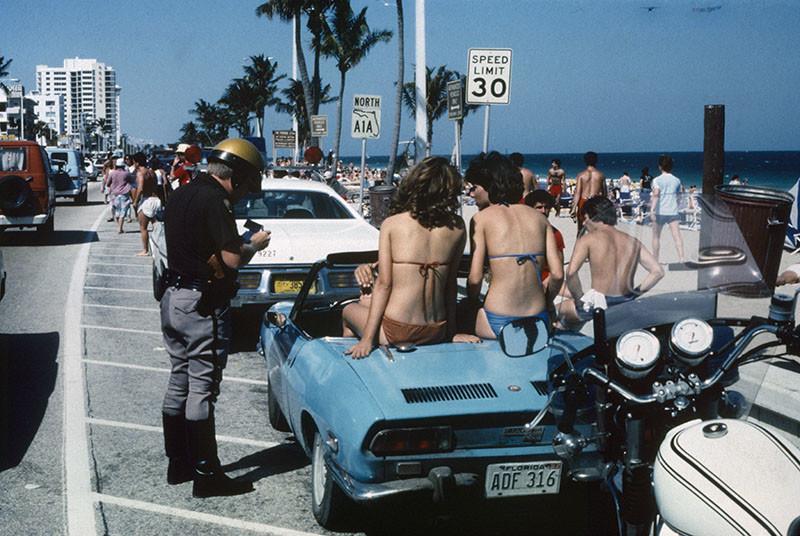

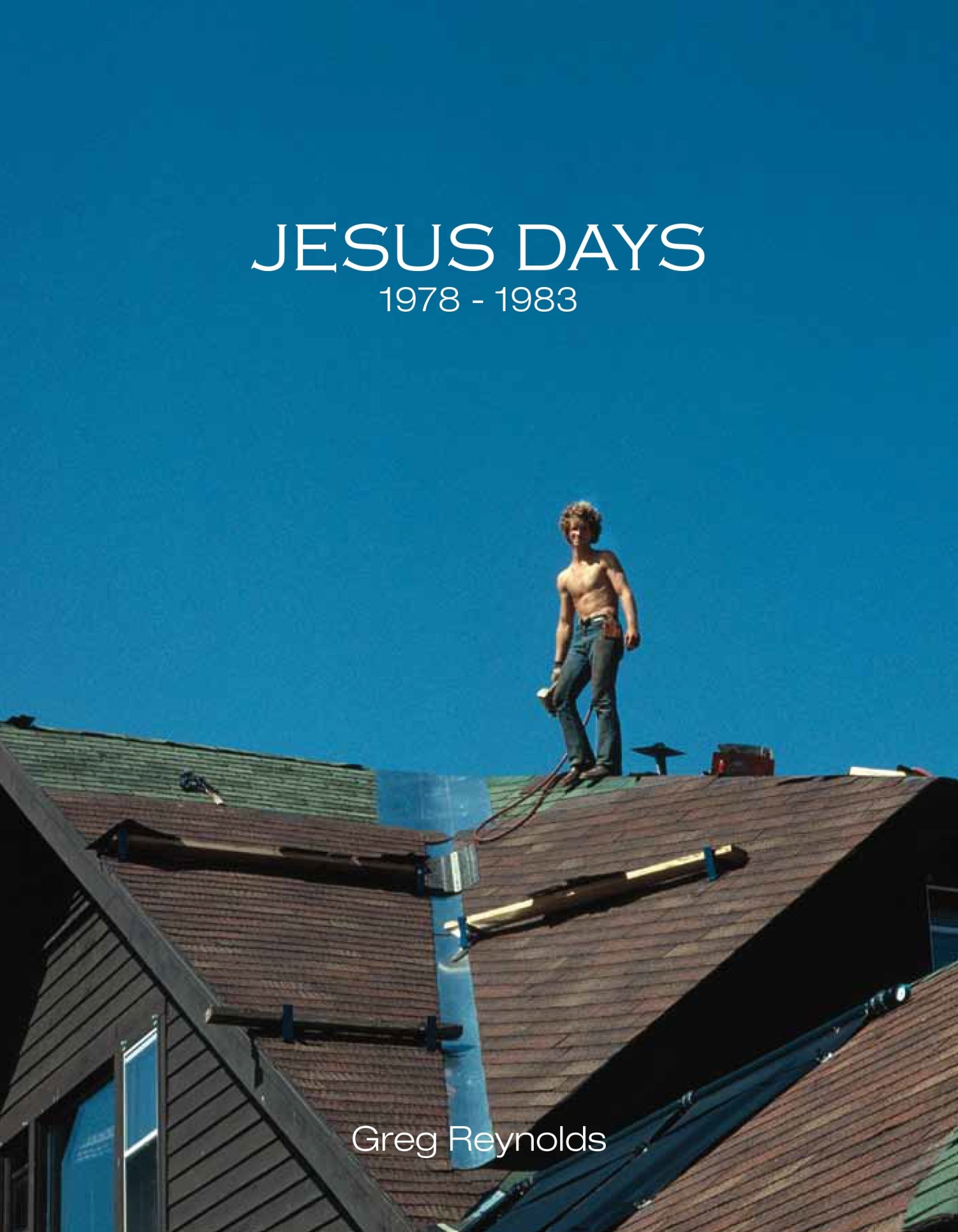

In the late 70s and early 80s, Greg Reynolds was an evangelical youth minister with the Intervarsity Christian Fellowship. He led Bible studies and prayer groups, travelled abroad for missionary work, and even preached to spring breakers on Florida beaches. But Greg was also struggling with his homosexuality. In 83, he came out, left evangelism behind, moved to New York to study at Columbia, and became a photographer. Twenty five years later, Greg rediscovered the first images he shot during his days in the Fellowship and published them as a book, Jesus Days: 1978-1983. His sunsoaked personal portraits aren’t merely momentos, but honest documentation of life in Southern evangelical America. On the heels of his recent book talk at Printed Matter, we caught up with Greg to find out more.

Tell us about your upbringing.

I was born in the 50s and grew up in the 60s and 70s in Kentucky, where religion and evangelism were very much a part of my world. I was raised Baptist and became a part of an interdenominational evangelical ministry in college. There were student movements that saw the college campus as a microcosm of the educated world and sought to make this space their mission for Christ. In many ways, it seemed more liberal than my Southern Baptist roots. As I finished college, I went on to work with the Intervarsity Christian Fellowship as a youth minister for a total of eight years. We were really sincere about what we believed — that our message was going to make a difference in people’s lives and the world. But at the same time, I was dealing with being gay and not being out, which forced me to examine my faith and myself.

When did you first become interested in photography?

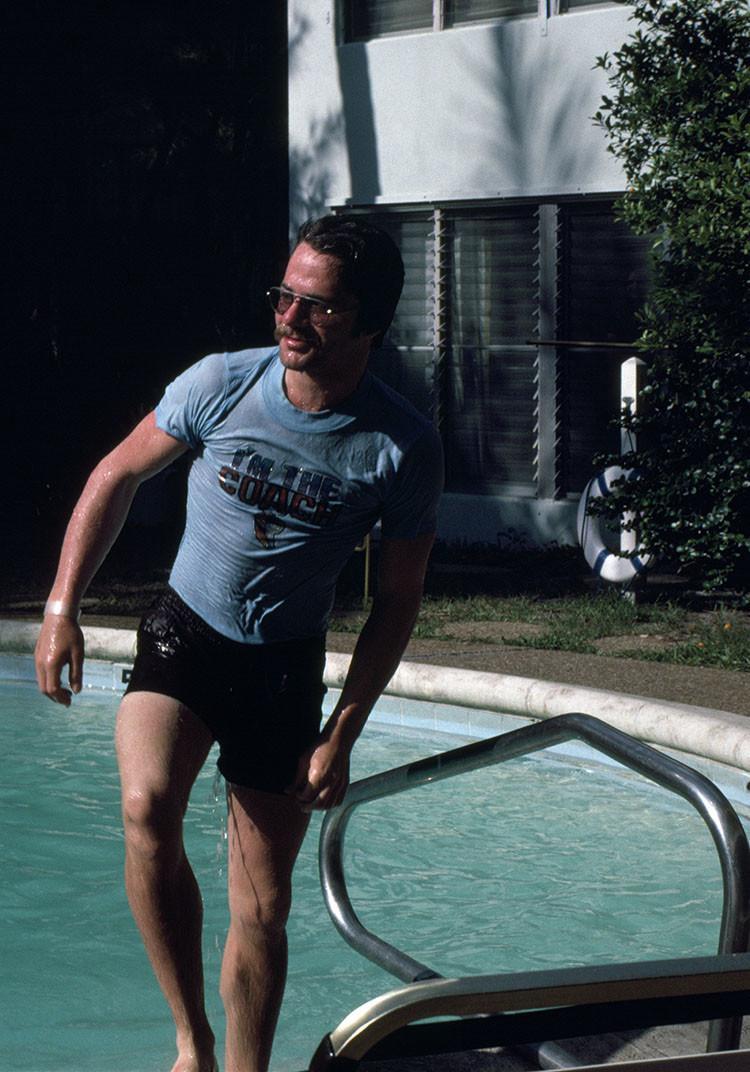

I received a 35mm camera for my birthday from another youth minister in 78. I had always had taken art classes in school, but I didn’t know any photographers and I wasn’t a part of a world where arts were the focus. So at that time, my intention was to do nothing more than make pictures that I liked. There was no pressure to do or become anything, but it became a passion for me.

Did you ever come in contact with other gay men during your missionary work?

It’s kind of strange: I would talk to people in such a way that I would acknowledge that I was having these feelings too, but that God was helping me to overcome them. I never quite believed that, but I wanted to believe it. I wanted to believe that I myself would be healed from these feelings. I had a girlfriend and tried to make that kind of relationship work, but I was pretty lost. I was trying to find my own path in a place where I wasn’t meeting other gay people who could advise me or say it’s okay. And at the time, you could be in a relationship and weren’t pressured or expected to have sex until you were married. So as a Christian and a gay man who couldn’t act on my sexual desire, it was very ‘safe’ environment for me. But that safety also made it scary to leave.

What motivated you to come out?

My last two years with the organization were the worst of my own personal conflict, but I was meeting with a Christian therapist who was really quite liberal and open and just wanted me to find who I was. I worked so hard for so long to be straight, and I came to realize that I either had to sublimate who I was or be who I was. Within that environment, I could never be a gay person. The only course that I could take was to leave. I was admitted to Columbia University’s graduate film program and moved to New York in 83.

When I came out, it was like stepping out of a memory. I went from a Southern environment where almost everybody was Christian to being around people who had no connection to that at all. In 83 and 84, things were changing politically and the AIDS crisis was becoming more known about. It was a scary time to come out. But looking back, coming out at that moment might have might have been the difference between being alive and not being alive today.

What motivated you to publish the images?

The project really began when I found boxes of slides and started looking at them after 25 years. So much distance made it feel like I was exploring a different person’s life, stepping behind my eyes and seeing what I saw. Because I had this distance, I could reexamine that life. I think my gaze now is a conscious gaze; there’s more intent. But when I look back at these pictures, they feel clean and fresh–kind of innocent.

What have you learned from this experience?

Even in the years following coming out, I never was 100% sure I made the right decision–there was always a feeling of guilt. In some ways, it’s given me a way of confronting the past and getting closer to it. I feel I’ve come away with closure. Some friends have told me that when I talked about that period in my life, I always seemed to be embarrassed about it. I’m not embarrassed anymore.

Jesus Days, 1978-1983 was published by Bywater Brothers Editions and is available from Artbook/DAP

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Greg Reynolds