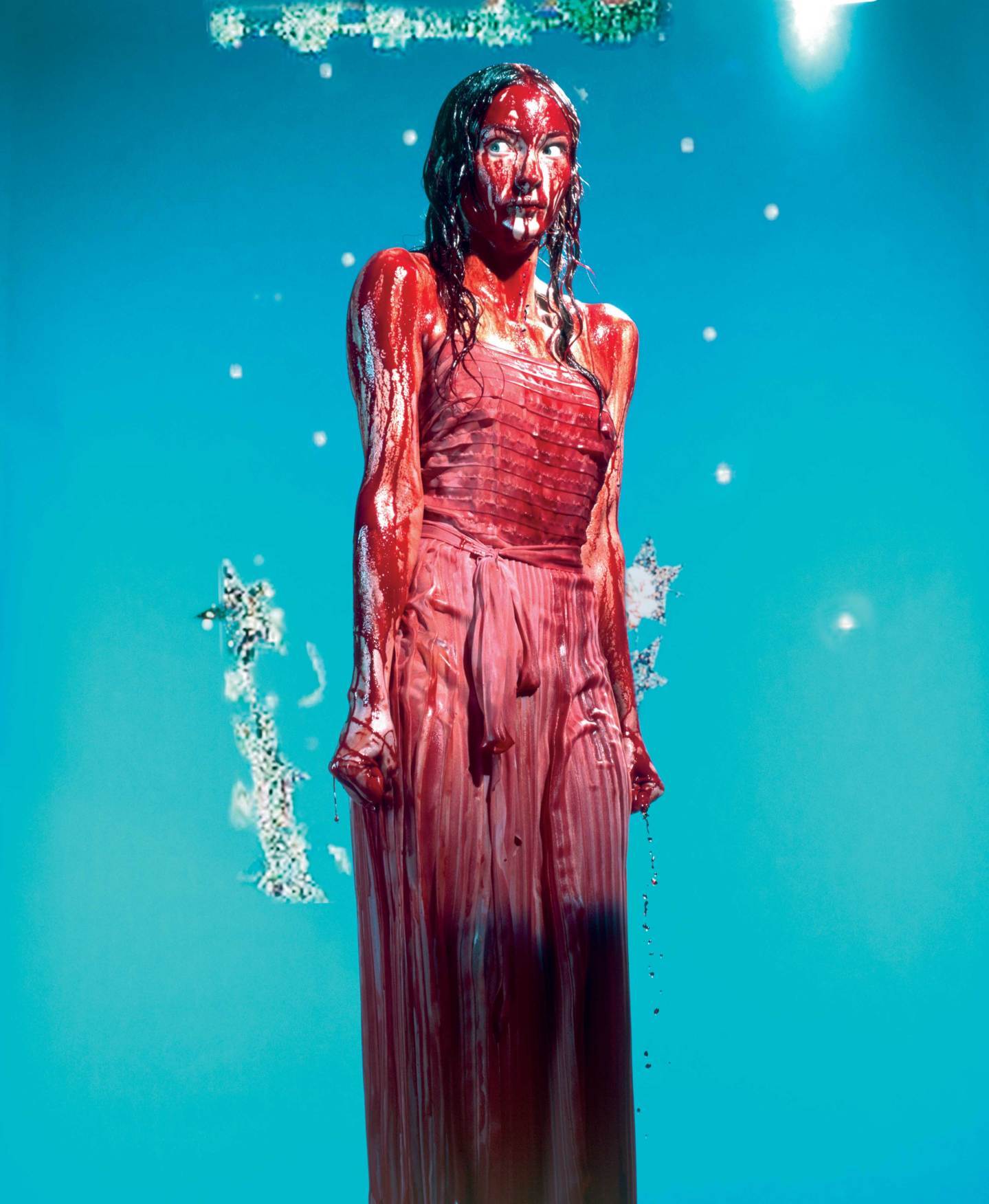

Welcome to the horror show – contrary, existential, furtive, Gothic, hedonistic, romantic and often very, very violent. Today’s nihilistic cultural landscape shows black on the outside for reasons that are now far more complex than merely feeling black on the inside. Suddenly, everything’s just hard: attitudes, beats, drugs, fashion, images, politics, sex, times. Restless and angry, feeling disrespected outside their own friendship groups and by those in authority, this is a cultural moment where the young and challenging are going for broke, in a manic phase of peer-to-peer exchange that might look messy around the edges but has a coruscating idealism at its centre. If this is hardcore, it’s time to settle the score.

Horror – the cataloguing of violent experience – is one of the most uncomfortable mirrors society holds up to itself, because the way a culture deals with death, loss and terror – horror’s components – magnifies its anxieties and fears utterly. It’s hard not to look at today’s world through blood-reddened eyes as a result.

In an insecure, polarised world where disaffected expression is portrayed as a public order problem and dealt with accordingly, incidents such as those above are the thin end of a wedge encompassing spring’s Paris youth employment demos or Los Angeles’ migrant marches, never mind anything to do with peaceful protest against global warfare.

We’ve done this before, back in Cold War days, when state-led paranoia and the threat of mutually assured destruction inspired a generation of conscientious objectors to present their visions of dystopia and post-Apocalypse in a Big Bang of urgent late 20th century artistry, comment and display. In the here and now, it’s possible to be hauled before police and questioned under the Terrorism Act for merely playing punk rock, as a 24-year old British Asian man detained for playing London Calling on his iPod found to his cost earlier this year.

In an insecure, polarised world where disaffected expression is portrayed as a public order problem and dealt with accordingly, incidents such as those above are the thin end of a wedge encompassing spring’s Paris youth employment demos or Los Angeles’ migrant marches, never mind anything to do with peaceful protest against global warfare. Unsurprisingly, the response from the young or disaffected is a hall-of-mirrors of blood and guts, more often directed inward than not: the heroin, crack and crystal methamphetamine destroying the marginalised and sidelined across the US and Europe; the phenomenon of ‘bug chasing’, where gay men seek out HIV+ partners; body modification, tattoos and scarification as conceptualised self-harm, beautiful to those who see elegance in cigarette butts and bruises, fairy tales revisited and sick-twisted into decadent tableaux straight from the original brothers Grimm.

Youth cultures historically contain a reactive element where opposition to an overbearing parent culture creates both agents and an agenda for cultural change. Rebellion is a healthy and necessary part of this process. Any follower of the style press knows this energy has fuelled every great subculture or movement since teenagers were invented, from CND to KLF, Teddy boys to grime, the Situationists, to punk, disco to rave – and these ‘cults’ are nearly always perceived as a threat to public order until they can be sold on as commercially viable. Ideas reach the assembly-line in record time; originality is in the eye of the beholder with the biggest wallet or best lawyers – those who internalised or parodied that art/commerce conflict by dressing up swashbuckler style found their look appropriated faster than you could say ‘Avast, ye landlubbers! Here be Primark’.

Although Larkin’s Law of Parenting still applies, even when our parents are supposed to be listening to Arctic Monkeys and bidding for old-skool trainers on eBay, what’s different about today is the impact of global commerce and relative subjectivity on even the most microcosmic situations. This means that traditional moral markers of God, leader or country are constantly shifting in impact and importance depending on your age, sex, or location: it is possible to Google your way to almost anything, be it musical knowledge that isn’t yours (yet) to a cheap holiday in someone else’s belief system, misery or hypocrisy in a matter of seconds, or to find a hero in your own country described as a terrorist in another.

The amorality of the world as a whole doesn’t offer much comfort to anyone looking for neat definitions of ‘good’ and ‘evil’. Artists such as Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jenny Holzer and Larry Clark don’t lose sight of this when questioned by those who self-identify as having ‘traditional’ moral values. Whose traditions?

Visually, the gore on the evening news is virtually interchangeable with both itself and scenes of destruction in films and war games; in Douglas Coupland’s novel JPod, one character focuses on the faux-gore of gaming as “a place to park my evil.” This blase attitude towards violence indicates its pervasiveness rather than a wish to be violent; the same novel anecdotally mentions teenaged joy-riders killed because “video-game physics” doesn’t work on real stolen cars. Counterintuitive thinking like this is redolent of Freakonomics and the writing of Malcolm Gladwell, new staples of the refusenik’s reading list, eagerly discussed by the technorati in the same breath as copy-left technology and peer-to-peer networking.

Visually, the gore on the evening news is virtually interchangeable with both itself and scenes of destruction in films and war games

There is something monumentally Hogarthian about the early 21st century: news of vast corruption of institutions emerges daily, to resigned shrugs, while modern-day celebrity scandals straight out of The Rake’s Progress provide ample distraction to a public convinced by good, solid evidence that there’s one rule for the elite and another for everyone else. Hogarth’s smoky, haunting visions of London in the early 18th century, driven by corruption and filth at every level, are a relevant reference point whenever politicians turn even uglier and the brightest stars are mad, bad and dangerous to know. Visitors to the Tate’s Gothic exhibition will also know that movement’s initial basis in post-revolutionary or satire rather than a fetishisation of Royal widowhood; both have become changed and charged by the skuzzy swoon of the newest Romantic movement and its retrogressive fans. Still searching for Albion? Look no further.

Internet communities are a well of sardonicism and irony, springing from an unwillingness to take any corporate or government statement at face value. In the corridors of power, reality is something the powerless must live with. When challenged by The New York Times to justify the Bush administration’s decision-making, one (unidentified but senior) White House aide quipped, “That’s not the way the world really works anymore… We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And when you’re studying that reality – judiciously, as you will – we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors… and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

Amongst the fearless, whether their expression centers on art, display, or making noise, horror isn’t about screaming in the dark any more. It’s about the suspense that’s killing us. Left in limbo from one day to the next over how much control – or self-control – is possible in such a hostile environment, mini-battles over individual physical and mental terrain are merely responses to the age of chaos in which we live, fight-or-flight conundrums written on bodies and minds, haunted by ghosts from the past and cultural doppelgangers. Whatever you decide to do, just keep moving forward unbloodied and don’t… look… behind… you.

Credits

Text Suzy Corrigan

Photography Nick Knight

Styling Gareth Pugh

Hair Peter Gray using Aveda

Make-up Alex Box using M.A.C.

Styling assistance MyQue Boyd-Kidd

Hair assistance K-Kay

Light Kinetic

Retouching Rob at Epilogueimaging.com Special thanks to Park Royal Studio

Model Felicity at Storm

Felicity wears vintage dress from Beyond Retro

[From The Horror Issue, i-D No. 267, June/July 2006]