On September 15, 1983, a 25-year-old graffiti artist named Michael Stewart was beaten into a coma by New York police after tagging a wall at First Avenue subway station. He died 13 days later, his cause of death listed as cardiac arrest. It’s a story that is still all too depressingly familiar 33 years later — the police claimed Stewart had become violent, struggled with officers, and ran into the street. Stewart was beaten unconscious before dying of his injuries. All eleven officers involved in the incident were later acquitted by an all-white jury.

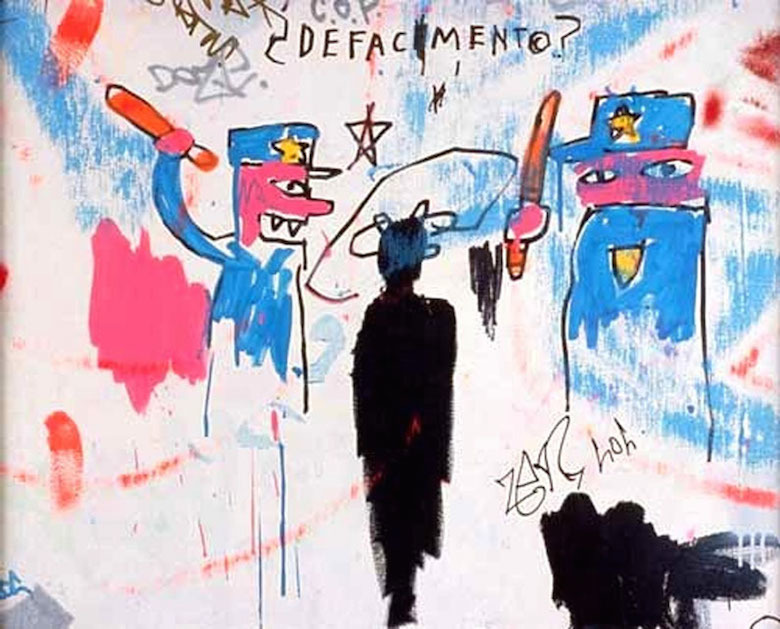

Stewart’s treatment while in police custody and the ensuing trials sparked debate concerning police brutality and the responsibilities of arresting officials in handling suspects. Another young, black artist affected by the event was Jean-Michel Basquiat, who went to his good friend Keith Haring’s studio in the East Village and painted Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) on the wall. Haring kept it above his bed until his death in 1990.

Hoping to increase awareness of the painting itself and the continued political importance of Basquiat’s work, New York-based writer and activist Chaédria LaBouvier has created a multimedia project exploring Defacement, Basquiat, and police brutality. The debut of the project and scholarship was at Williams College in Massachusetts, where a talk was held. The painting is the subject of programming — which LaBouvier also curated — while it’s on view at the Williams College Museum of Art.

This work is personal for LaBouvier. Her own brother, Clinton Allen, was killed by Dallas police while unarmed in March 2013; and after his case was no-billed by the Grand Jury, she and her mother co-founded Mothers Against Police Brutality to support other families who have lost children to police brutality. I spoke to her about the importance of the project, Basquiat’s legacy, and how his work ties into the conversations we’re having about police and black and brown bodies more than three decades after Stewart’s death.

How did you get into Basquiat?

My parents were early collectors of his work before he got super famous; we had three Basquiat drawings above the couch. My mom really stressed to me that Basquiat was black, that he was a black man in the art world, and that art is something that was open to me. In that sense, Basquiat is someone that’s always been there in a way, and when it was time for college, I went to Williams College in Massachusetts. When I got there, I knew I wanted to study Basquiat because I had grown up around him, so to speak. I started researching him when I was 19, a time before things like Google and YouTube were available. I would skip class in my sophomore year to go spend the weekend in New York and hang out in bars in St. Mark’s and in the Lower East Side looking for people that knew him, and eventually found old friends of his. I’d meet someone and they’d give me someone else’s number who’d introduce me to someone else — I met a lot of people that way and they taught me a lot about him. When I was talking to these people about him, one of the paintings that would come up a lot was Defacement — it’s not a famous painting because it’s been in private collections for pretty much its entire existence, but it was a painting that always came up. I’d seen it in books but never in person and I didn’t know who owned it. It wasn’t until the internet became a bigger thing and I could Google it and find out about Michael Stewart that I understood the deeper levels to it.

Can you explain your project and the inspiration behind it?

This painting is not just socially relevant but also has a lot to contribute to Basquiat’s body of work and how we look at it. I think there are important issues of identity and politics that we don’t look at enough, at least academically, so the point of the project is to provide a foundational level of scholarship for this painting. It was really important to me that this wasn’t in an ivory tower, or ensconced in a museum where it’s not always accessible to people. It’s about creating a scholarship, creating a discourse, putting Basquiat in that discourse about police brutality, and creating a digital and accessible place for the research to exist and for that to happen.

How did the project come about?

I was invited back to Williams College because of the work I was doing with activism and police brutality with Mothers Against Police Brutality (MAPB). Williams was like, ‘we need to have a conversation about police brutality in this privileged space and you’re the most qualified to do that’ — I think it’s safe to say I was one of the first writers for a mainstream women’s magazines in the States to write about the issue — so that’s how that happened. The talk went really well and I did some workshops, and they asked me to come back if I wanted to do anything else. At the time, I was also working at the Now’s The Time Basquiat retrospective in Toronto, which is when I actually saw Defacement in real life for the first time, and I was like, ‘this is amazing, I wanna do a talk on Basquiat and Defacement.’ I collaborated with [Williams] and created the project and was able to secure the painting as well which I never expected initially. It’s very difficult to have something new to say about Basquiat, and with the project at Williams not only did we have something new to say but we had something really relevant to say about a national issue with one of the most popular artists of our time.

What conversations do you hope to inspire with this project and what kind of discourse do you hope will come out of it?

I hope that it gives people an entry point into looking at police brutality in a new way. I think sometimes people have fatigue because it feels like this is happening all the time and you can’t keep up with the names, but I think it’s important to look at the fact that this was happening in 1983, and that Basquiat was talking about this. In a way I think it’s a gift, he’s giving us his thoughts on this conversation that we’re having; and I think that given how popular he is, I think it’s important to engage with his actual work and engage with his politics which I don’t think people do enough of.

So the discourse that I hope that we have is that we better engage with his work and his politics, and that remember Michael Stewart who is at the heart of all of this — this is someone who started a very contemporary conversation about police brutality in NYC, and he’s been largely forgotten. I hope this conversation brings him to the forefront where I think he should be. In terms of police brutality, we need to change what we value, and when I say ‘we’ I mean white people. What this comes down to is police brutality as a symptom of white supremacy — we’re having these issues because white police officers believe that they have the right to kill unarmed black and brown people, and society indemnifies them from that and gives them a free pass. That structure was set up by white people, for white people, for the preservation of whiteness, and we really need to contemplate what that means and why we have that. People of color have been saying police brutality has been an issue forever, but it’s only when white people feel that it’s an issue that these things matter which is really unfortunate. Since it’s set up that way, we really need to demand more from whites, and white people need to demand more from themselves, because we are literally dying from a very complacent and mediocre level of compassion.

How would you describe Defacement as a painting?

It’s a painting about the loss of a life, the loss of Michael Stewart’s life, and what that meant. Basquiat has a very ennobling way of looking at blackness — he doesn’t look at black trauma without this term that I coined called the ‘exit routes of majesty’. What I mean by that is that these ‘exit routes’ that he employed allowed him to look at the traumatic aspects of blackness with an ennobling safety mat. When it gets too painful, there’s a way out into majesty and royalty which are two of his favorite subjects. I think that Defacement is really important because it’s one of the few times that Basquiat allows himself to look at blackness without any of those crutches, and I think that’s really important to mediate on. So to answer your question, I think Defacement is about a 22-year-old who is on this incredibly fast ascent to the top of the art world and yet he is becoming aware of the limits of assimilation and the limits of that success when you have a black body. I think he’s really struggling with the juxtaposition of this unparalleled success and this money and this access, but yet understanding that Michael Stewart could have been him too, and what that says about the limits of progress, the limits of assimilation, and the vulnerability of a black body.

You chose to have the painting displayed in the reading room at Williams College rather than in a traditional gallery space. What was your thought process behind the placement?

The painting has always been in intimate environments and I think it’s more fitting — it was drawn on Keith Haring’s wall in his apartment and he had it cut out and put in a gilded rococo frame that was over his bed until he died. After that it was given to a collector — Nina Clemente, who was Francesco Clemente’s daughter. Keith and her had a very special bond and I think he got it so right to leave it to her. It was on the wall of the loft she grew up in for many years, and then it was in storage. We wanted people to feel this painting, and I think when it’s on a museum wall people would approach it a bit more clinically. I think the placement makes a potentially very volatile piece more welcoming; keeping it in an intimate environment was our way of including Keith Haring in this history and in the project too, I think we owe him a lot.

Credits

Text Niloufar Haidari