It’s easy, with hindsight, to see how we all became so enamoured with the idea of ‘heritage’: that loosely-defined, reductive term that came to encompass any brand either exemplifying or drawing on the tenets of traditional clothing and manufacturing. The explosion of interest in utilitarian garb and ‘Made In England’ seals of approval around the turn of the decade coincided with a global financial crash the likes of which we could barely have conceived of. Ours is an a-historical generation “increasingly preoccupied with the future” (as Tony Blair’s favourite sociologist Anthony Giddens put it in 1998), but as the projections and pre-suppositions of the markets burned to the ground around us, the tangible grounding of history – our oft-overlooked heritage, in other words – became very appealing indeed. Coupled with the explosion of readily-available information in the internet age, the discourse of mainstream fashion increasingly began to encompass topics that were previously the reserve of niche Japanese subcultures and fusty old men at flea-markets. We became obsessive about the provenance and weight of our raw denim; everybody with half an eye on the Sunday supplements could tell you about the tangible qualities of the Vibram sole on the bottom of their Red Wing boots.

Inevitably of course, the appeal of ‘heritage’ soured, something that has been the subject of numerous think pieces within the marketing sector and beyond over the last twelve months. The second you could walk into Topman and buy facile approximations of a US-made work boot with none of the actual rugged qualities, things began to feel increasingly empty again. For a trend that was rooted in the materials and production methods of the early twentieth century, the mass-homogenisation of the fast fashion world was always doomed to eat it alive. The bubble burst and with that, if you are to believe some of the more sensationalist reporting around the issue, ‘heritage’ was dead.

“It is blindingly obvious just how much things had been watered down,” says John Alexander Skelton, whose MA collection recently won the prestigious L’Oreal Prize and follow up is being presented during Frieze by pioneering boutique Hostem, the stockist he has chosen to work with exclusively. John sees ‘heritage’ – ever the loaded term – purely as “fraudulent marketing.” This is despite the fact that many aspects of his work invite the label. Based in London, John is an outspoken export of the Northern working classes, and it is evident from his words just how much the post-industrial, post-Thatcher backdrop of his childhood has caused him to look back further to more halcyon days of UK manufacturing. Indeed, he is committed to autonomously producing entirely within the British Isles, using traditional fabrics and manufacturing methods. What then is it that places John in a different to league to, say, The Real McCoys, a key Japanese brand of the ‘heritage’ trend that focused entirely on meticulous reproductions of utilitarian clothing from the same period John draws on? Perhaps it is John’s firm assertion, backed up by the striking pieces he brings to life, that he thinks of himself unequivocally as a ‘fashion designer.’ It is a term that was almost something of a dirty world at the height of the heritage craze. “I think [fashion designer] is a very misunderstood term and one that involves many cliches. The way that I understand it, it’s about a constant journey… it’s about creative modernity.” Where the heritage trend was in some respects about both looking backwards and standing still, designers like John appear to be introducing a narrative dimension; lending newfound forward propulsion to their old-world inspirations. Rarely is it acknowledged that within these traditional spheres, the focus on functional clothing actually resulted at the time in truly innovative design and manufacturing. By drawing on ‘heritage’ markers in the way that John and his contemporaries do, they are breathing new life into them – in a way that is impervious to the death-throes of fleeting trends.

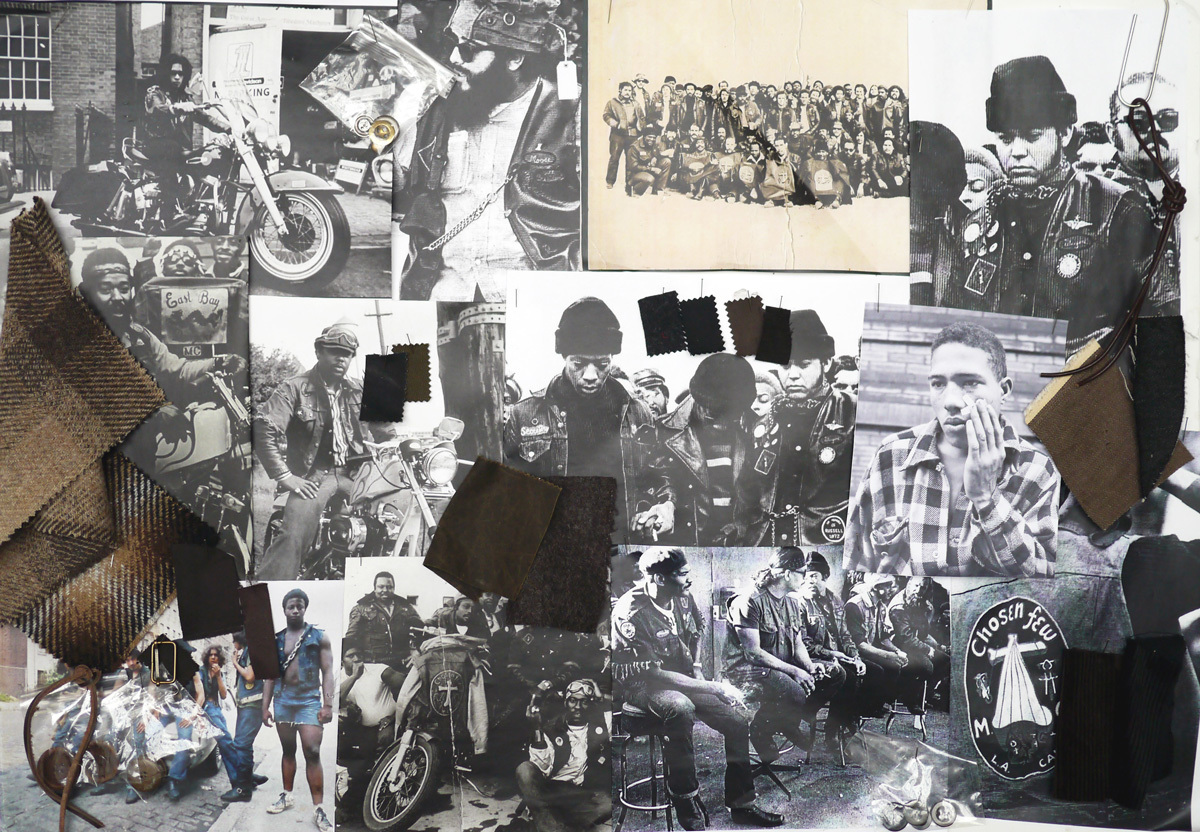

This also holds true for Nicholas Daley who is, like John, a graduate of the St. Martins MA programme and now stocked in Hostem (his brand also has a strong presence in renowned Japanese store International Gallery Beams). When discussing his influences, he immediately jumps to Yohji Yamamoto, who along with Rei Kawakubo remains synonymous with the Japanese avant-garde. A fashion designer through and through. Where Yamamoto’s silhouettes might admittedly and frequently draw on the old-timey subject matter of his favourite photographer August Sander, they do so in an inherently detached manner. Nicholas summons much more intimate iconography: the diaspora-driven musicians tied to his Caribbean ancestry; the proud Scottish tweediness from his mother’s side of the family. “It’s important [for my work] to explore aspects of my personal heritage and then understand how this partakes in a wider cultural conversation,” says Nicholas. “Multiculturalism is innate within my own identity and within the British identity too.” Whilst these reference points might inevitably call to mind the recent LVMH Prize-winning work of Grace Wales Bonner, there is perhaps a closer affinity to Nigel Cabourn, an elder statesman of vintage-inspired design who Nicholas also cites as a major influence.

“I feel more like a person who just loves history and in particular famous events from British history [than I do a designer],” says Nigel from Tokyo, where he is currently entrenched in one of his many global research trips in advance of upcoming collections. Positioning himself as he does, it could also be said that his deceptively progressive work is often unfairly viewed in the same light as straight repro brands such as the aforementioned Real McCoy’s. However designers such as Nicholas (and even select retailers such as LN-CC, who in their original incarnation were great champions of Cabourn within a high-fashion/luxury arena) took notice of the way Nigel injects personal design quirks into his meticulously assembled pieces. “I’m inspired by vintage pieces but I use that inspiration to create new, individual styles,” he says.

Again, all of this points to personal narratives and high-concept thematic elements more readily associated with the fashion world becoming intrinsically tied to notions of heritage. By levelling the playing field in this respect, designers like Nicholas and John free themselves from the shackles of easy categorisation, whilst at the same time avoiding the superficial outcomes that so many brands have fallen victim to when trying to incorporate superficial heritage elements. “I think about origins and histories in terms of how they can be activated through modern design,” says Nicholas. Likewise for John: “the only traditional elements that retain a value for me [are the ones that] I can incorporate into my own work whilst still taking it to a new and modern place.”

As Nicholas points out consumers are better educated than ever before – “the power of the internet has really informed people of the smaller, niche subcultures out there.” For all the negative connotations that the ‘heritage’ trend might currently possess, it was perhaps integral for preparing customers for this new generation of provocative designers (who of course themselves spent their formative years amidst its commercial dominance). Now though, designers like Nicholas and John seem liberated: boldly revelling in the perfect storm of creativity they have conjured. Forward-facing design instincts fused to old-world quality craftsmanship in a way that stretches far beyond the tropes of an appealing marketing campaign. Just as we were in 2008 when the bottom fell out of the banks, it feels like we’re again entering unprecedentedly uncertain times socio-politically. Designers that bridge the personal and the cultural, who fuse a globally informed mindset to preciously localised industries, who refuse to accept that our golden age exists only in the past… Designers like that, they feel more relevant than ever.

Credits

Text James Darton