Andy Warhol is one of the most ubiquitous artists of all time, and Andy Warhol – From A to B and Back Again shows us why. The Whitney Museum’s sprawling exhibition is the first Warhol retrospective in the U.S. in nearly 30 years. It includes over 300 of the multidisciplinary artist’s works, from his iconic Elvis portrait to the lesser-known drawings he made while working as a commercial illustrator in the 50s.

What makes Warhol’s work so timeless is its unfaltering relevancy. Exploring fame, glamour, and mass media, sex, politics, and tragedy, the late artist tapped into all aspects of American culture. As a child of immigrants, Warhol was endlessly influenced by his role of both insider and outsider, particularly when it came to filmmaking. From the early 60s until his death in 1987, Warhol created hundreds of films — silent, black-and-white, shorts, and feature-length — exploring everything from interpersonal relationships to our celebrity obsession.

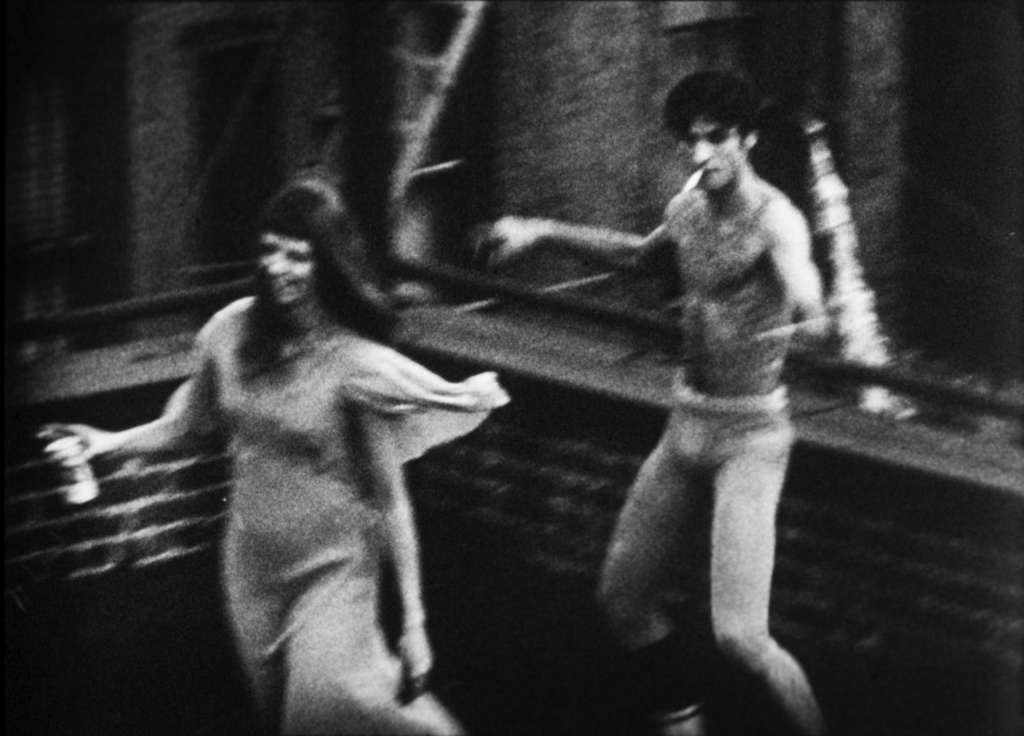

Dance & Movement

Warhol’s obsession with dance and movement of the body went far beyond his Dance Diagram illustrations, appearing in his film work as well. Warhol’s passion took root during his early college years, when he discovered dance clubs. He greatly admired professional dancers and choreographers, often using them as subjects in his films. Some of Warhol’s avant-garde dance collaborators through the years included Lucinda Childs, Freddy Herko, and Yvonne Rainer. In Warhol’s Jill and Freddy Dancing (1963) the American Ballet Theater School–trained Herko dances on a rooftop in the Lower East Side with Jill Johnston, one of the Village Voice critics.

Interpersonal Relationships

To the public, it may have seemed as if Warhol had no close personal relationships. However, quite the opposite was true. In some of the silent films Warhol shot on a hand-held Bolex camera, the viewer is granted an up-close look at some of his closest friends and collaborators — many who were fellow NYC artists, dancers, and poets. One of his dearest friends was his assistant Ronnie Cutrone, an SVA student who began coming to The Factory when he was still in high school. The pair’s close relationship is highlighted in a Factory Diary installment titled Andy Warhol & Ronnie Cutrone Fingerpaint, Pat Types, Rush Hour at Subway (1974). Other films, such as Haircut (1963) series and Sleep (1964), were inspired by intimate acts such as cutting a friend’s hair or watching someone in bed. Warhol watched (and filmed) his friend John Giorno for five hours and 20 minutes.

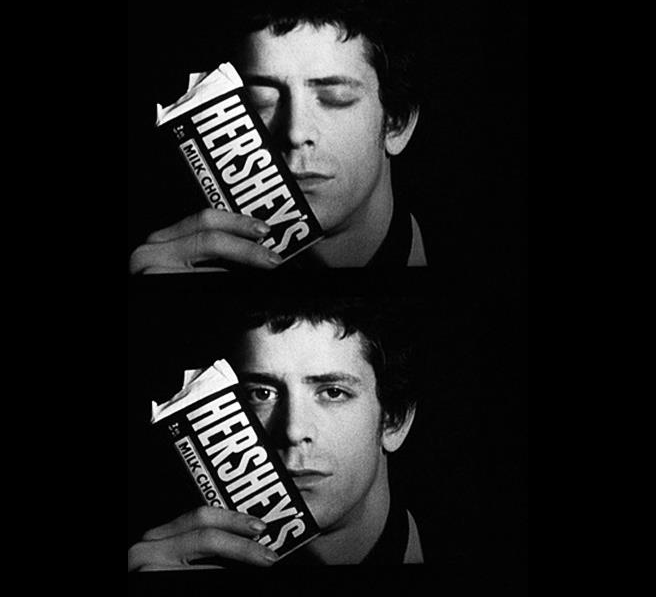

Television and Media

Influenced by his job as a commercial illustrator in the 50s, Warhol became progressively interested in how advertising and television shape our behavior. One Warhol series that touched on this topic was Screen Tests, a collection of over 400 silent black-and-white films that the artist made in the mid-60s. Many featured stars of the downtown NYC scene, such as Lou Reed, Nico, and Jane Holzer, interacting with products such as a bottle of Coca-Cola or a Hershey’s bar. A scene from Jorgen Leth’s 66 Scenes of America titled Andy Warhol Eating a Hamburger (1982) stars Warhol himself eating a fast-food hamburger. Warhol asks the question — does the viewer’s focus rest on the product being sold, or the star selling it.

Hollywood and Glamour

Warhol’s obsession with Hollywood was no secret — his large collection of movie star portraits included everyone from Marilyn Monroe to Marlon Brando to Ingrid Bergman. This infatuation started early — when Warhol was a young child he would collect scrapbooks full of celebrity photographs he’d sent away for. As he got older, this celebrity obsession spilled into his films, allowing him to examine the nuanced themes of glamour, desire, fame, and gender portrayal. Warhol’s fascination with Hollywood made its way into his work in more subtle ways as well. His 1965 film Poor Little Rich Girl, starring Edie Sedgwick, was named after the famous 1936 Shirley Temple movie.

Portraits of Personalities

Throughout Warhol’s career, he connected with a countless number of people from all walks of life. His cohorts ranged from artists and gallerists to famous athletes and movie stars, many of them also becoming his art subjects. From fly-on-the-wall footage of David Bowie’s days spent at The Factory, to Bob Dylan’s Screen Test (1965), Warhol’s films immortalize countless icons, all with a familiarity that feels increasingly rare.

Warhol on Politics

Although Warhol publicly claimed he had no interest in politics during the government turmoil that marked the 60s, his work shows us otherwise. From the portraits of Jacqueline Kennedy produced shortly after her husband’s assassination, to Since (1966), a film in which Factory members reenact JFK’s untimely death, Warhol’s work was undoubtedly influenced by politics and the media’s perception of national tragedy. Warhol’s complex relationship with politics of the 60s makes you wonder how the politics (and celebrity politicians) of today would have informed his work, especially in a world driven by social media and the quest for 15 minutes of fame.

Music as Muse

Throughout Warhol’s career he collaborated with countless upcoming and established musicians of that time — including, notably, designing album covers for The Rolling Stones and Aretha Franklin. He even briefly managed The Velvet Underground, and eventually tried his hand at directing music videos, or at least one music video — for The Cars’ “Hello Again” off the band’s 1984 album Heartbeat City. Warhol also appears in the video, naturally, though his screen time is more limited in the censored version that played on MTV. Who knows where this career trajectory would have taken him if he didn’t pass away only three years later?

Queer Performativity, 1965 – on

The Factory was not just a place of artistic creation but a space where everyone could be themselves — embodying, exploring, and performing their queerness openly. The space also served as the backdrop for many of Warhol’s films. In Vinyl (1965 ), S&M fantasies take centerstage in an adaptation of A Clockwork Orange; and in Camp (1965), friends of The Factory hold their own queer variety program, complete with a drag performance from Factory regular Mario Montez and a dance number by legend Paul Swan. Warhol’s 1964 film Couch — starring Allen Ginsberg, Jane Holzer, Jack Kerouac, and Peter Orlovksy, amongst others — depicts the many sexual encounters that took place on The Factory’s iconic red couch. The result was a feature-length film that was completely pornographic in nature. When the cameras were rolling, nothing was off-limits.

Andy Warhol’s TV, 1985-1987

Later on in his career, Warhol created Andy Warhol Television, which aired on MTV from 1985 to 1987. The talk show, hosted by Warhol himself, provided an intimate look at some of the most influential icons of that time. One episode shows Debbie Harry in conversation at The New School, discussing how rising rents were affecting NYC club culture, while another depicts a chat between Kenny Scharf and Keith Haring at Scharf’s NYC apartment.