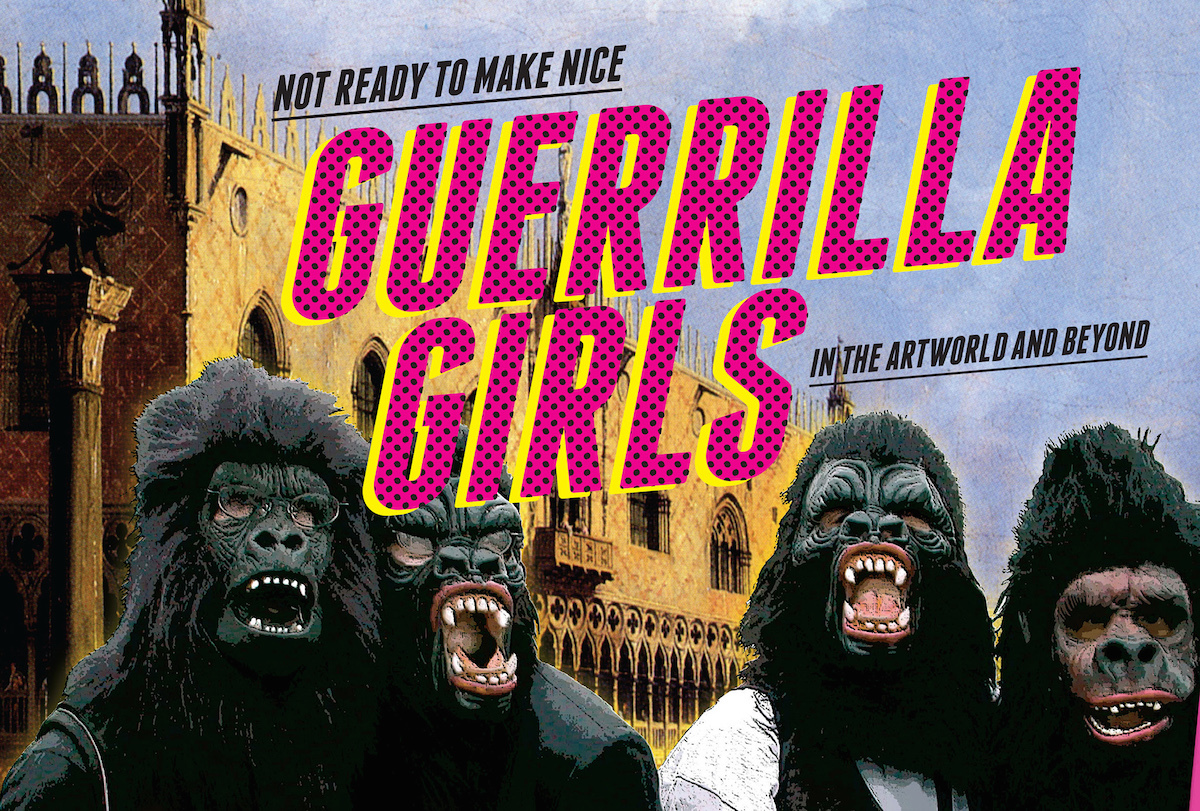

It’s been 30 years since New York art collective Guerrilla Girls roared onto the scene with their unique brand of activism, bringing into focus the gender and racial inequality in the art world. Wearing gorilla masks, the seven women, who went by the aliases of late women artists, plastered the streets with posters highlighting depressing statistics – their messages were humourous, accurate and impossible to ignore. At the time, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) was holding an exhibition titled An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture, which claimed to represent the most important contemporary artists. The show featured 169 artists – only 13 were female and even fewer were artists of colour. Three decades later, more than their legacy lives on – the group still wear the masks, unconvinced that their work is complete.

Are they right? Despite the vast improvements women have made in the industry – in most industries – since 1985, the numbers would indicate yes. For their June issue, ARTnews focussed solely on women in the arts. Breaking down the statistics, Maura Reilly found that between 2007 and 2014, of all the solo exhibitions at MoMA only 20 per cent of them were by women artists. In the UK, Tate Modern did not fare much better – women only represented 25 per cent of the pie, and despite making gains in 2009, women artists make up just one third of the roster at this year’s Venice Biennale.

You need only look at auction results for quick insight into the pay gaps between male and female artists – a Jeff Koons work sells for US$58.4 million, while the highest price paid for a work by a living woman artist, a Yayoi Kusama painting, was US$7.1 million. To determine “the world’s 100 greatest artists”, German publication Manager Magazin’s annual list Kunstkompass (‘Art Compass’) considers how frequently an artist exhibits, their press coverage and the median price of their work. Last year, just 17 were women. (Watch Girls actor and artist Jemima Kirke lay it all out in this clip for Tate).

In the vein of the Guerilla Girls, Melbourne artist Elvis Richardson keeps track of the gender divide in the Australian arts scene via her blog CoUNTess. “I mean things have obviously changed over the years. There are more women represented in commercial galleries, in collections and museums, but it rarely gets over 30 to 40 per cent,” says Richardson, who points out that 70 per cent of art school graduates are women. “Fifteen years out of art school and you kind of ask yourself: ‘how come my male peers seem to be doing so much better than my female peers?'” Richardson thinks it is important for galleries to hold all-women exhibitions – seeing it as a necessity, rather than tokenistic. It’s an opportunity, she says, for women to be a part of the narrative and assert their influence in contemporary art practice.

Art is subjective, sure, but the argument that an artist’s gender is irrelevant, that the quality of art is based on merit alone, just doesn’t hold true. If curators are exhibiting fewer women artists, if galleries are representing fewer women artists, if collectors are buying fewer women artists, if the press is reviewing fewer women artists – how can we deem what is significant when the full diversity of work is not being seen? In the same edition of ARTnews, artist Chitra Ganesh makes a great point: “I read an interesting article about the ‘unrecognised woman artist’ which points to how prevalent this narrative is: it says ‘she is unrecognised,’ not ‘we didn’t recognise her,’ and so evades naming the structures that produce this lack of recognition.”

How more opportunities can be created for women seems obvious; increase the number of women power players – the curators, the collectors, the dealers. And today there are more women than ever holding senior positions at galleries, giving hope that we will continue to see further advances in diversity. Still, art is big business and it is the elite, which is overwhelmingly made up of wealthy white men, who decide what has market value. Even with women directors at the helm, commercial galleries will be inclined to represent the artists who bring in the bigger buck, who more often than not are men.

Which is why the Guerrilla Girls, Pussy Galore, CounTess, Sleepover Club and other feminist activists who continue to crunch the numbers are so important. A name and shame game is sometimes what it takes to initiate change. “People like to have the perception that art is based on merit and quality – and that’s the playing field everyone is on,” says Richardson. “No one really wants to have the numbers in their face and to have to consider ‘oh, isn’t it odd that so many people with merit are men?”

Related: Melbourne Collective Sleepover Club address inequality in the art world.

Credits

Text Jean Kemshal-Bell