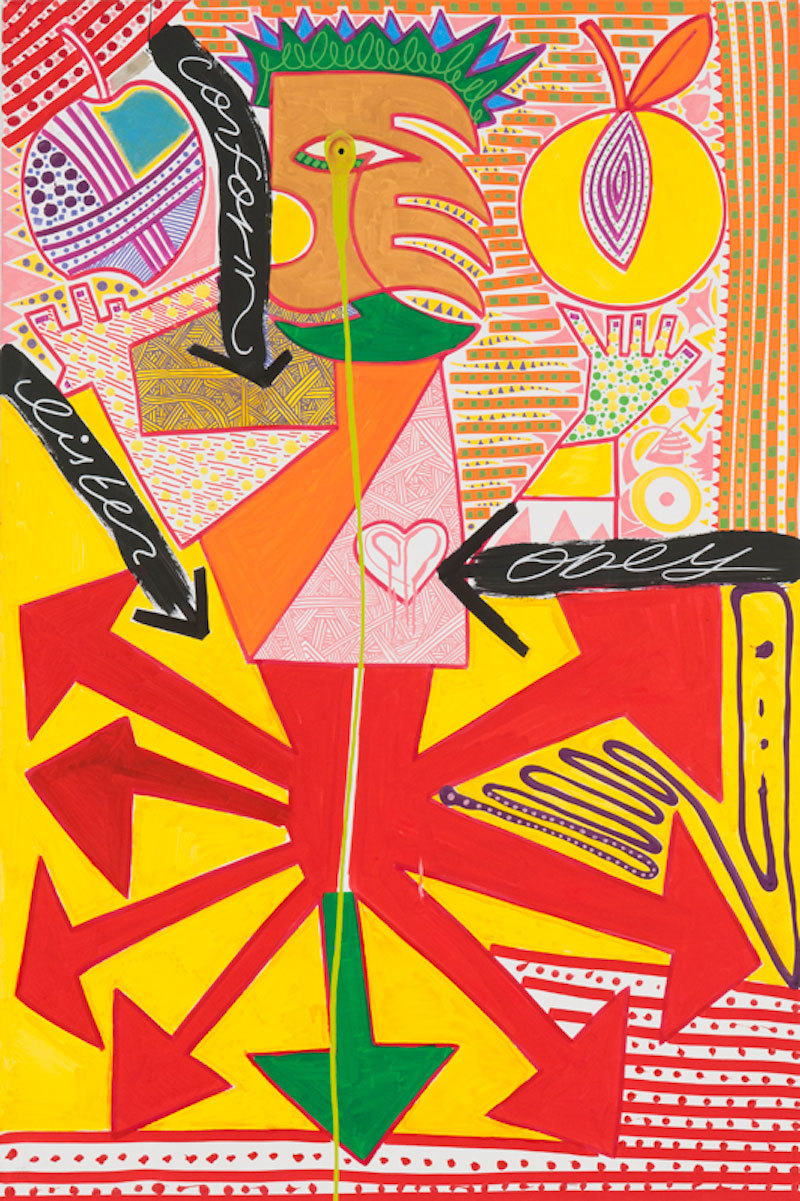

Google the name Abdullah Qandeel and an immediate picture begins to form. A 27-year-old classic enfant terrible, showy, undeniably talented — a Saudi Arabian playboy artist cavorting with Instagram models and power players across Europe’s luxury playgrounds. In and out of the news for his two arrests in the UK and the US for painting all over the five-star hotel suites he tends to stay in. He bailed on our first scheduled interview because of a hangover. As with all things though, the caricature is too simple a stereotype to last for too long. After spending a few hours talking with Abdullah in Jeddah via Skype, a different character emerges. Qandeel is also an artist doggedly committed to his craft; ambitious, politically conscious, a culturally progressive citizen of his country. He has ridden the kicks, jibes and the laughter of his peers and his own (extremely wealthy and successful) family in one of the toughest places in the world to come out as an artist. Last month he was officially Commended by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia — his nation’s highest arts honour. He’s having trouble finding a wife. He could be Jeddah’s answer to Charles Bukowski. In any sense though, Qandeel has come a long way from when even his best friend advised him to “stop making scratches on walls and getting yourself arrested.” For your information, he’s extremely proud of both.

When did you first get into art? Who inspired you as a painter in your own right?

As far back as I can remember, I always liked drawings. At school I loved the fact that you had an instrument – a pencil – to make interesting patterns. The ability to make something outside of your own mind that other people could see.

I made my first real piece called Divorce after my parents divorced when I was about 20. I decided to move to New York about two years later. I got invited to a party thrown by a guy called David Barokas called the ‘Art Party’ that he threw for a woman called Safia El Malequi. I walked in and I could tell what the coolest table was, so I went straight there and sat down. Nobody knew I was an artist at that point; I didn’t even consider myself an artist at that point. But Divorce was on my phone as a background. Safia saw it and said she really liked it. The next thing I know she’s inviting me to do an exhibition at her gallery in Monte Carlo. That was my first show. I found a backer called Karim Karaman and it’s gone from there.

What’s the environment like in Saudi Arabia in terms of the arts? Is there enough encouragement amongst the younger generations?

It’s getting better. I’m not going to lie to you and say it’s phenomenal. It’s getting better. There’s a tremendous amount of artists now that weren’t there before. There were ‘closet’ artists, but after my jailing, after I came back – I’ve really seen other artists understand that it’s ok not to think like other people, or do things like other people. I think people maybe saw me as an example. I’m certainly not the best example – but an example of being true to yourself and to who you are and still surviving.

Both the 6 Columbus in N.Y. and the Mayfair Hotel in London arrested you for acts of vandalism of their property – however both have kept your ‘vandalism’ intact. How do you feel about that?

Look, let me tell you the story for the record. I got to the Mayfair and reserved two double-floor suites, and I told them, ‘If you don’t mind, could you kindly remove all of the furniture from the suites because I would like to paint in there and I will make sure that when I leave it’s in the same condition as I found it.’ They left a painting on the wall, I had some fun people over and during my painting session, I painted on top of that painting. When I checked out, after paying for my rooms, the guy at reception called me and said I still owed them six grand for the painting. I told them to show me the receipt and I’d happily pay it. Not to mention that I added value to that painting anyway. I get another phone call from that same guy confirming that the painting was actually worth £3000. So firstly I was confused how the guy had added another £3000 to the painting and secondly I asked them for an email to outline all of this. I never got an email back from them. I left town, I visited some clients, I came back to London to the Edition Hotel and the next thing I know I’m getting arrested at 1AM in my room on the charge of destruction of property. I just found it totally bullshit. They had actually told my assistant the day before that we could pay it off in due course; meanwhile they’re calling the police at the same time, saying yes, it’s ok to arrest me.

I don’t have a habit of destroying property; I have a habit of making art. Look, if someone doesn’t want to accept an increase in value on a painting, which is actually a commodity – then I’ll pay for the painting that I ‘damaged’. I mean I wouldn’t do it to a Picasso, but this one looked like it was from Camden Market. At the 6 Columbus I just painted the whole wall in the penthouse. I’ve heard they’ve still got it up and are keeping it as an original of mine.

The way I like to look at it is that I got arrested for making art, and I think that’s beautiful. When I made some headlines in New York about it, I felt very proud; I felt happy that people got to see a Muslim arrested for art and not terrorism.

Where do you place yourself in terms of this new Saudi artistic movement? Who do you think is pushing it forward internationally and domestically?

I’m one of the pioneers of art here, I believe. The older generation didn’t communicate themselves very well; they didn’t have the technology or the desire. The art wasn’t inspiring. I actually think we’re living in the most exciting time right now. Look at things around you, we’re dictating with technology: things are more sustainable. Things are stronger, better, sexier, cleaner, more thought-out. So I’m part of that time now – I’m lucky to be part of this generation. In terms of who’s changing things, I’d go with Abdulnasser Gharem Ajlan, I’d go with Ahmed Mater.

What do you want your art to say? Do you feel it reflects your country in a specific way?

First of all, we [Saudi Arabia] are going through a bad PR period right now. I think we are in general, as Muslims. I think also that everybody recognises the fact that art is a great vehicle for expressing unification and humanity. Nine out of ten articles in the paper these days you’re going to read have something about war or bombings or death or explosions related to Islam. Something is wrong. So art can be a unifier. We understand beauty the same way as a Jew, a Christian, an atheist, or even a fucking devil worshipper can understand beauty. Beauty… is simple.

Saudi Arabia’s in my DNA. I’m being given an award for art from the Heritage and Preservation Society; they believe my work is worthy of preservation for our country’s history, can you imagine that? That’s how much I mean to this country and that’s how much my country means to me. It’s changing: I wanted to talk about this guy Prince Mohammed bin Salman. I have a tremendous amount of respect for what he’s doing: the number of progressive policies he’s put through office in one year… He’s the Defence Minister and Head of the Council for Economic and Development Affairs. He’s waged war on the Houthi fundamentalists in the South of the country that were backed by Iran; he supported the defence of Syria from fundamentalists. All I know is that right now the region is fucked, so it’s important we stay positive and make art and inspire the kids that are coming up. Our population is very young (46% of the Saudi population is between 15-35), so what I do is going to impact them. We need the next generation to listen to people like me and to the freedom of thought, as opposed to this fundamentalism garbage. When you look at Paris and Belgium, it’s just so sad. These people should be stripped of their ability to claim that they are Muslims.

Would you call your work subversive?

I would say it’s subversive against the fundamentalists, absolutely. It’s also beautiful. Maybe that’s what’s subversive. But it’s subtle. At the end of the day, you can’t make a car turn too fast, or it’ll flip. We are under Sharia law here, you have to respect the religion, but the fundamentalists take it too far. When we don’t recognise women’s rights, that’s the biggest problem we have. But I truly believe that will change. It’s coming slowly but it’s coming.

Some might say that there are elements to Saudi culture that put limits on an artistic movement. Do you think that’s true or is it stereotype?

Absolutely. I believe in freedom of speech but I also believe that if you have a political system that has created stability in the country for over 128 years – that’s important. We have water, food and electricity all subsidised here. We don’t pay tax. It’s a very comfortable way of life that people have become used to. At the end of the day, the government is doing their best and the new direction they’re moving in is progressive. Prince Mohammed is young and he just gets it – he’s inspired all these young people to get out of their homes, to stop smoking weed and to start working, you know? When you give women rights and you stand with them, saying “You are part of our society,” it helps break the crap that has been going on in our country. I look at it as kind of a blessing in disguise that the oil price has come down, because it’s allowing us to implement policies at a faster pace. We have to shift away from being an oil-dependent economy into an economy that’s dependent on its people.

Artists such as Manal AlDowayan have now staged groundbreaking female-only contemporary exhibitions (entitled Soft Power) – how does this relate to them having such relatively little standing and rights in Arabic culture?

Yeah, I like her work, I’ve bought a few of her pieces myself. A woman called Safeya Binzagr though was one of the first artists to have a solo exhibition here and who now has her own museum – she’s an important pioneer. You said the right word though – it’s culture, not religion. It is a cultural trait. If you look back at the ‘old days’, there was a culture here and it was a Bedouin culture. It presided mainly in the East side of the country. Then we had a port in Jeddah where people were more rounded and mixed and liberal, because that’s what trading and importing does. The Bedouin culture was more conservative because when you’re in the desert, there are only two things that matter really: number one is water and number two is your women because that’s your ability to procreate. You had to protect your women, which is why things have transcended into less female roles in society and more male. But now we’re bringing women into the workplace. Things have changed for the better. Culture always changes, always shifts.

How important is royal patronage to an artist in Saudia Arabia in 2016?

I think it’s extremely important because that’s how you can compete on an international level. The concept of patronage goes back to the Medici family in Florence; it’s not something new. It created some of he greatest artists in the world and that’s where I see myself going. I think the royal family is looking to invest in people rather than art; it’s the people that matter. Personally, I don’t have one ‘proper’ patron or allegiance to one; I speak with a few of them. In that sense I’m still part of the school of thought that if you’re doing well enough on your own, you don’t need to think about other people unless there’s a specific project you want to do with them. That’s why I haven’t joined a collective, that’s why I’m not represented by any galleries. I’m kind of stubborn like that and I believe in that. You like my work and want to show it? Go ahead. You don’t like it? There’s the door. It’s my work. I write the rules here, that’s why I’m an artist.

What’s next for you?

After my next exhibition this year I’m stopping for two and a half years. I really want to build a residential tower or a hotel – maybe a combination of the two. One of my dreams is to have my own hotel brand that doesn’t arrest artists for being themselves.

Credits

Text Karim Khan

Images courtesy Abdullah Qandeel