As I watched Hillary Clinton’s chances of winning the presidency dwindle last Tuesday night, I remembered the fact that this presidential campaign has awoken and empowered a side of America that has always been here. In Times Square, looking at the giant LED screen that showed an increasing number of states turning red, I thought about my commute from Bushwick into Manhattan that morning. While being visibly Muslim on any form of transportation is a less than comfortable experience I felt like I was under a more menacing magnifying glass than usual. I felt like my presence was more noticed and further unwanted. Donald Trump’s rhetoric of bigotry, discrimination, and scapegoating has been felt by all oppressed people. Unfortunately, it has also given people with hate in their hearts a license to act on their biases.

I saw four white male Trump supporters in their red hats walk past me in Times Square and I felt their gaze in a new way. I looked at them wondering how they could live among people like me and have a disregard for the consequences presented by a Trump presidency. I wondered if they saw me as human. And Donald Trump is not unique in his bigotry. I have felt a hostile gaze at Hillary Clinton rallies as well. Once, a fellow Hillary supporter called me a terrorist.

Taking all of this into account, I tweeted: “I’m scared that today will be the last day I felt somewhat safe wearing my hijab.” I said “somewhat safe” because bigotry didn’t manifest overnight or even because of Donald Trump. Bigotry is as American as I am. Still, the majority of my fellow Americans refuse to recognize this.

I wore my traditional hijab for a few hours on the morning of Wednesday, November 9. (I converted to Islam in college, in May 2015, and began wearing hijab full time in March 2016.) I sent a note into work letting folks know I would be offline the whole day. People at work were supportive and understanding; this was not the case for everyone I encountered. As I ran some errands I felt an even more intense gaze than the day before, I was even stopped on the train. A woman came up to me on the verge of tears, mouthing the words, “I’m sorry.” While it was obvious that she meant well, it was also very apparent that something had changed. And I did not feel safe.

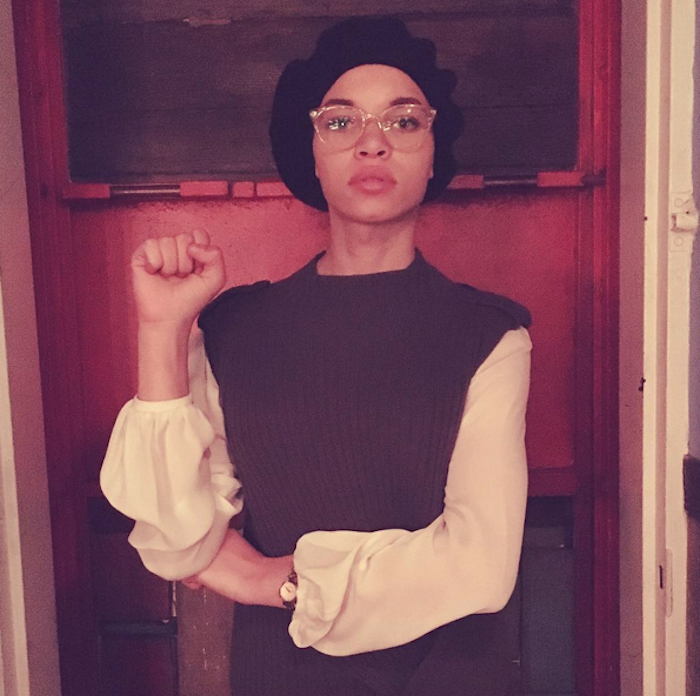

My decision to take a break from wearing hijab was made when I got a call from journalist, filmmaker, and activist Rokhaya Diallo indicating that she wanted to interview me near Trump Tower. Trump Tower felt like the epicenter of Trump’s America and I was certain that his supporters would be even more empowered by the sheer proximity to their leader. I did not think twice before walking to the nearest clothing store to buy a hat.

I changed clothes and lamented what felt to me like a step toward safety. I mourned the death of American freedom as bigotry and the very real threat of physical violence scared me from exercising the right to express my faith.

While hate crimes continue to be reported, well-meaning allies have urged me to continue wearing hijab, to protest, to be “brave.” I thought to myself, what shame is there in hats? What shame is there in protecting myself? I know my fear is valid, but it seemed like folks were eager to doubt me. I am unapologetically Black and I am unapologetically Muslim. My faith is not dependent on my adherence to a given individual’s perception of Islam. Moving forward I will stay covered, whether that means wearing hats, beanies, or berets. It is not cowardice that is informing my decision, it is survival.

As a Black American Muslim woman I am fully aware of the reality of discrimination in this country. Like many Americans, my lived experience is not a simple one; I live at the intersection of Islamophobia, anti-Blackness, and misogyny. Trading my hijab for more “palatable” headcoverings does not liberate me from bigotry, it makes me feel a bit more safe.

The glimmer of hope that I hold onto now is that Trump’s administration will unite marginalized people toward a common goal and force allies to realize that they must center the voices and lived experiences of marginalized people. If all of us who comprise “the other” are given the space and liberty to enact the path toward our collective liberation, I believe it will come a lot sooner. For folks of privilege, this means having uncomfortable conversations at the dinner table, speaking up against hate, and taking steps to be a genuine ally.

The next four years will undoubtedly be a period of huge challenges for marginalized people so I urge everyone to exercise self-care and remember: bravery comes in many forms.

Credits

Text Blair Imani

Image via Instagram