Police intervention in UK club culture is not new. From Margaret Thatcher’s disdain for the rave scene to the repeated closures and inevitable death of Sheffield’s Niche — the home of the bassline scene — few genres avoid the extended reach of the long arm of the law. However, arguably fewer genres have seen more targeted discriminatory procedures forced upon it than grime.

While grime’s past run-ins with the law have been well publicized, in 2016 grime has made its way into the homes of middle England and is arguably bigger than ever before. With this middle-class love for a genre born in London estates (the British equivalent to projects), you would think that we might have moved past the stigmatization of the genre, that the scene might be better understood by the police. That doesn’t seem to be the case.

“Urban” can encompass many things when you live in London, but under the gaze of the police and the infamous 696 form, that term can mean the difference between a hassle-free career as an artist or being continuously targeted by the police under the guise of protection. “One year at Carnival the police just told us we couldn’t come,” explains Sam Adebayo of Parallel Music and manager of Angel and WSTRN. “They said that our ‘lives were in danger,’ that they’d ‘had some intelligence.’ We asked why and they’d simply say, ‘oh, we can’t tell you.'”

These sentiments were echoed by the cancellation of a Just Jam event at the Barbican in 2014. “Public safety concerns” were given as the reason why the likes of Omar Souleyman, JME, and Big Narstie were unable to perform at the venerable arts institution. While well publicized at the time for its discriminatory undertones, Just Jam’s doomed Barbican production is far from a rare occurrence or something to look back on in disdain. It forms part of a wider issue that means if you happen to be an “urban” artist, you’re going to have a harder time making it. “I don’t think they understand what sort of impact that has,” Sam continues. “For one: you’re stunting the growth of the artist’s career. [Police] need to be aware that this isn’t just a hobby that people leave the house to do, this is a serious living and it needs to be taken seriously.”

“It seems to depend more on where you’re situated in the pecking order of the nightlife out here,” says Bok Bok, co-founder of label and club night Night Slugs. “The O2 Arena manage to do these arena-sized events and by some miracle that passes through with police approval. I’m glad it does, we need those events to happen. But then when you look at smaller club nights where potentially, from a police perspective, there’s less risk, surely they should be pretty harmless?”

With little to no transparency from the police — the Metropolitan, City of London or the Association of Chief Police Officers have all failed to give any indication on their rationale — is this seen as a direct targeting of both black artists and black audiences? “I think there is a generalization,” Sam says. “I remember Wireless this year asked us for the name, date of birth, and address for everyone performing and their entourage. That’s actually not legal. We were even supposed to have a guest on the day who they wouldn’t let perform. We gave the info over beforehand with no issue, yet on the day we were told they couldn’t perform and that they shouldn’t even be on the site. I just don’t understand.”

In my day job as a promoter and booking agent I’ve been asked to give the private information for a literal list of artists provided by the Metropolitan police that only consisted of black, grime acts on an otherwise diverse line-up.

This “generalization” — or racial profiling for use of a more appropriate term — is something I have been asked to cooperate with by the police personally. In my day job as a promoter and booking agent, I’ve been asked to give the private information for a literal list of artists provided by the Metropolitan police that only consisted of black, grime acts on an otherwise diverse lineup. The Met asked for the names, addresses, and dates of birth of not only the artists but their friends, family members, and tour crew. It’s an extension of that infamous 696 form but compiled completely without the artist’s knowledge and handed over to the police.

I didn’t comply, naturally, but does this prove police tactics are changing? Discriminatory as it is, the 696 form is at least public knowledge. Now that more under the radar surveillance tactics are being adopted in its place, how are the lives and careers of black artists affected?

When asked if he’s been treated any differently as a white artist, Bok Bok doesn’t hesitate in his response. “Absolutely I’ve been treated differently.” While not seen as a part of the grime scene directly, Bok Bok has found himself heavily influenced by it, and as such an observer of the scene’s progression over the years. “What I do want to say is that we’ve had a free pass at Night Slugs as we’re not seen as part of the grime scene,” he explains. “If anything, it just shows you the hypocrisy that’s there because the music isn’t going to be that different.”

I was around when the 696 form was implemented, which caused a lot of problems for promoters. Raves were being shut down anyway, but 696 was a more formalized way to do that; an institutionalized means to oppress certain minorities or certain demographics that are throwing parties.

While keen to point out police intervention “isn’t a problem for me,” longstanding grime stalwart President T agrees it does still have an impact elsewhere. “The whole 696 form gives them the right to pick and choose who they allow to perform. I don’t think this is fair, I’ve seen numerous artists who I know for a fact pose no threat at all and just make cool music not being allowed to perform.”

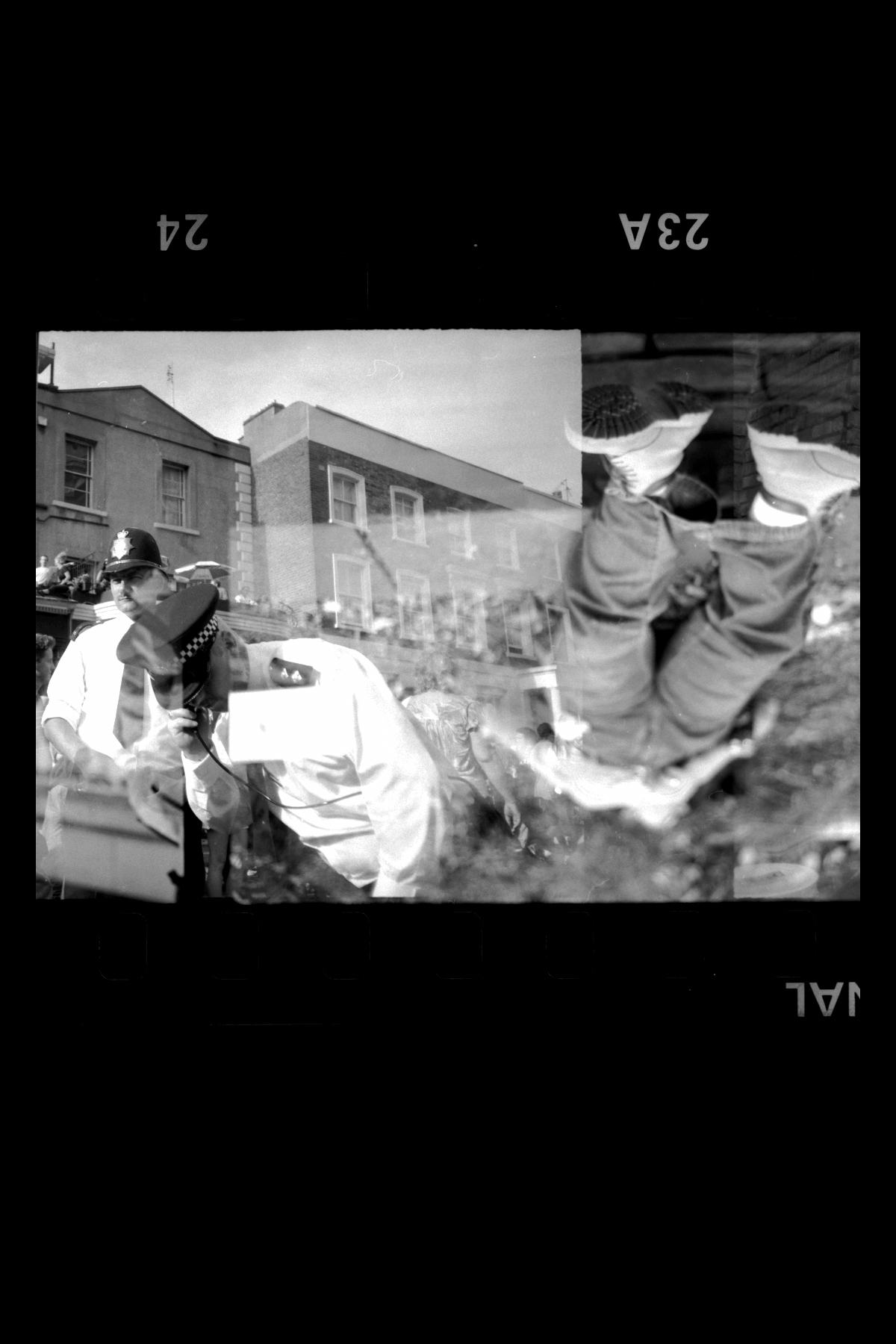

This obviously forms a problem in how the black music scene in the UK is viewed as a whole by the police, yet this is not a sole problem faced by an “urban'” genre or even London itself. In March police forces in Croydon were accused of racial profiling by Dice Bar owner Roy Seda after licensing officer Sgt Michael Emery banned bashment being played at the bar, deeming it an “unacceptable form of music.” And despite the amount of YouTube clips you’ve seen of police officers wining at Notting Hill Carnival, year on year the weekender is forced to accept increasing police measures to ensure the festival’s go-ahead. It’s part of “a long-running campaign to shut Carnival down,” says the #BlackLivesMatter group who will be at the carnival this year to peacefully protest against just that.

The whole 696 form gives them the right to pick and choose who they allow to perform. I don’t think this is fair, I’ve seen numerous artists who I know for a fact pose no threat at all and just make cool music not being allowed to perform.

Further afield Manchester’s Craig Dobson of the long-running club night Chow Down tells of how after booking JME in 2012, its organizers were called in for a police meeting to speak about how their “clientele was going to act” — the first and last time this has happened in a five year history.

Thankfully in 2016, the opportunities to make a career out of grime are undeniably greater than back in the Nokia 7600 days. But after years of police intervention and stunted growth within “urban” genres, how can the genre move forward?

“The most important thing they [the police] need to do is actually care that this is someone’s job,” Sam explains. “I don’t think they’ve worked with the artists and managers enough. If they did, they’d have a better insight into what’s going on. Grime is in a different place and the people who come to these shows aren’t there for trouble, everyone is genuinely there for the music and that’s it.”

“There hasn’t ever been any actual problems at any of our tours. Not one,” agrees Kevin of Dice Recordings, home to Big Narstie, Dullah Beatz, and Izzie Gibbs. “You’ve got more independent labels now and more people who understand the music. How can you continue to care about something that hasn’t brought any drama?”

“I don’t feel targeted by the police because of the genre of music I do. I bet there’s a fed driving around right now banging ‘I Don’t Care Bout the Law,'” laughs President T, an image I’m eager to witness. “I swear on my last national tour the only time I saw police was outside a gig I did in Bristol and that’s because a bunch of white Uni students were fighting each other in the street.”

The grime scene’s dedication over the years to keep on doing what it does despite the challenges is what will keep it thriving far beyond its “second coming.” While it’s somewhat disappointing to think that a wider acceptance is what’s needed to allow for progressive action, what comes with it is the knowledge that the genre is not going anywhere. There will continue to be problems, gigs will continue to be shut down and “urban” genres will continue to be targeted. But it is now too ingrained in our culture for it to be stifled anymore; it is a voice of Britain and no form can change that.

Credits

Text Jack Needham

Photography Adrian Philpott