At the end of last year I attended an event where a very well-known female ‘voice of her generation’ was interviewed by a bestselling author and celebrity feminist in front of an audience of over 2000 people. After a question from the audience that drew attention to the lack of diversity in said guest’s output was deftly answered, the host then weighed in and confronted the accusations of ‘racism’ that had been levelled at her online. “How can you be racist by exclusion?” she said at least three times, ‘how?’ Already alienated by the cosy view of female empowerment being shared in the room all night, I left troubled by the lack of outrage in the room (and later deafening silence on Twitter) and at the host’s inability to understand the complexities, and indeed the richness of contemporary inclusive feminism at the end of the year 2014.

As part of the London Short Film Festival I put together my own event to try to work through some of the frustration sparked by that evening. The event looked at female representation in music videos, but I wanted to look beyond the normal debates around the objectification of women’s bodies to discuss something I’d been thinking about that pertained to more intricate differences that I felt were being explored by some of my favourite acts. I wanted to explore the lure and power of identifying with a feminist image that embraced the complications of gender, race, class and capitalism.

In the last couple of years there have been some loud voices in the music industry making some bold statements about feminism and their relationship to it. Lily Allen told us it was “hard out here for a bitch” and attempted to take down Robin Thicke’s particular brand of misogyny. But her feminist statement led to her being accused of unthinkingly privileging her own, white, body over the black bodies of her dancers, and that her feminism was exclusionary, old fashioned – not intersectional.

In the US, Beyoncé, took the words of author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and mashed them up into an audacious new statement in her song Flawless, which she then performed at the VMAs in front of a neon sign that read “feminist” whilst grinding on a pole and spitting “bow down bitches.”

Wherever you stand on either of these stories, what became pretty clear from the thousands of tweets and comment pieces that they generated was that the term “feminist” is pretty confusing and loaded right now.

At the talk last week, it was asked why we were looking to the entertainment industries for our feminist leaders. This, our panel and audience argued, is not where we will find them, it’s where we will find rampant capitalism, objectification and cultural appropriation. Despite this rational and important truth, the allure of identifying with the images of celebrities is hard to ignore, it is in many ways, how we understand who we are. The visceral nature of these images means they become an incredibly powerful way that we process our own differences, however superficially they have been drawn for us. Yet, it seems that the more powerful the woman in terms of her media attention, her brand, the more diluted her feminist message becomes – so maybe we’re just listening to the wrong people.

There are many artists in the underground whose work deftly explores how complicated it is to be a woman of colour in the music industry. They are an antidote to the often exclusionary more mainstream understandings of what female empowerment is supposed to be.

The title of the discussion was Is it peculiar that she twerk in the mirror? a lyric from Janelle Monae’s track Q.U.E.E.N. Electric Lady, the album that Q.U.E.E.N comes from deftly explored the need for women of colour to reclaim their image in the world. Q.U.E.E.N (an acronym for Queer, Untouchables, Emigrants, Excommunicated, and Negroid) is the ultimate statement on the need for complexity and contradiction in our understanding of feminism. Monae’s style is a straight up call to arms, “categorise me” she challenges, “I’ll defy every label.”

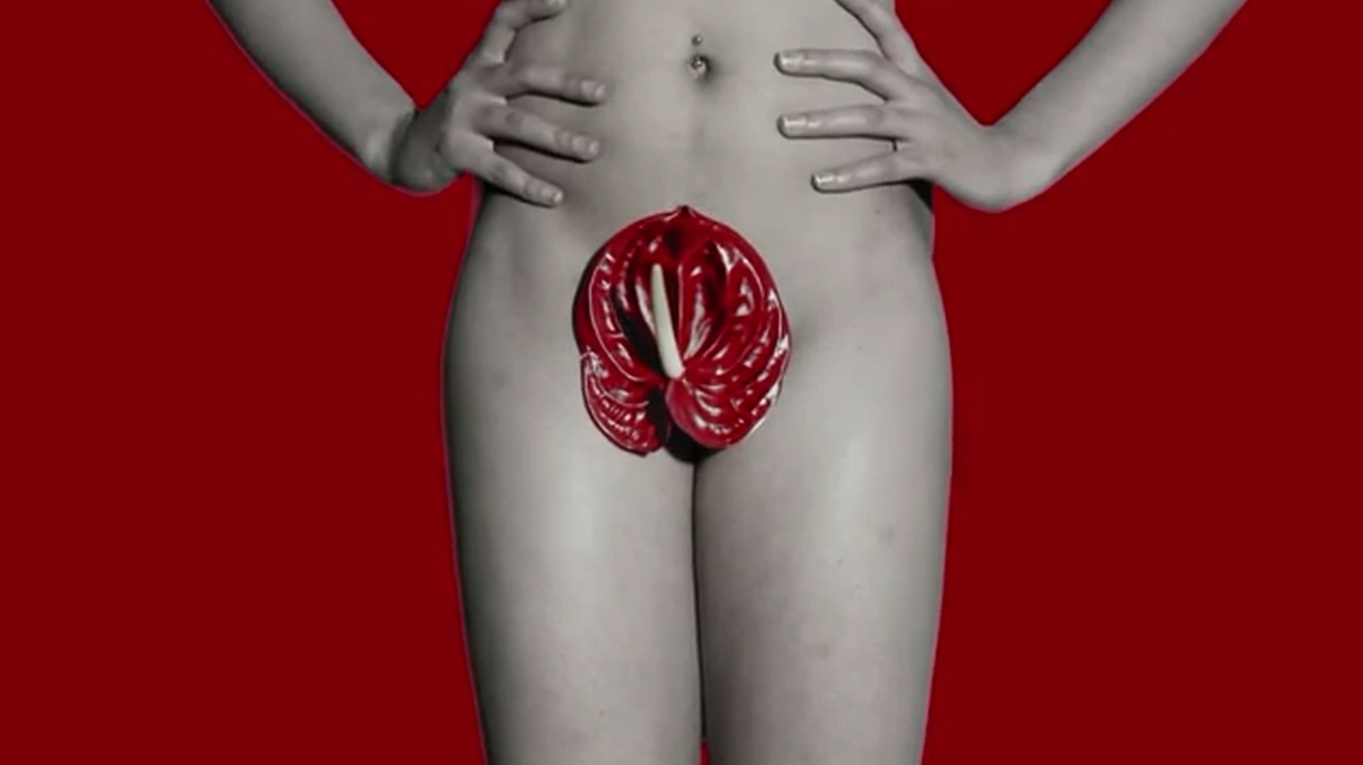

More recently, in the UK, FKA Twigs has become a mesmerising artist; her ethereal visuals, distinctive voice, Afrofuturist style and representation of her body are a refreshingly disorienting mix and signalled a young woman playing around with identity and experimenting, questioning, changing her image. As a woman of colour who is continuingly questioning what that means in the variety of life situations I find myself in, Twigs’ experimentation is invigorating. Less so is the mainstream press’ need to categorise her into well-worn and entirely meaningless categories based on their understandings of her blackness. They say “alternative R&B” when what they really mean is “confusing black girl,” and in one fell swoop obliterate the nature of a young woman’s individuality.

No one summed up more clearly how deep rooted questions of identity are for young women of colour than Azealia Banks in a recent interview with New York’s Hot 97 radio station. Taking aim at the cultural appropriation of the music industry, her tough girl image twice cracked, causing her to break down. Azealia spoke of a lack of recognition not just because she is different, but because she feels different and channels that feeling into complex art that is hard to place. This confrontation of the reality and effects of exclusion is something that anyone that identifies with the term feminist in the year 2015 – on any level – needs to pay attention to.

Is it peculiar that she twerk in the mirror? took place on the 16th January 2015 at the ICA, London as part of the London Short Film Festival. The panel consisted of writer Aimee Cliff, academic Emma Dabiri and filmmaker Grace Ladoja and was chaired by Jemma Desai.

The event was curated by Jemma Desai from I am Dora, a curatorial initiative that explores how women relate to one another through the medium of film.

Credits

Text Jemma Desai

Still from Hide by FKA Twigs