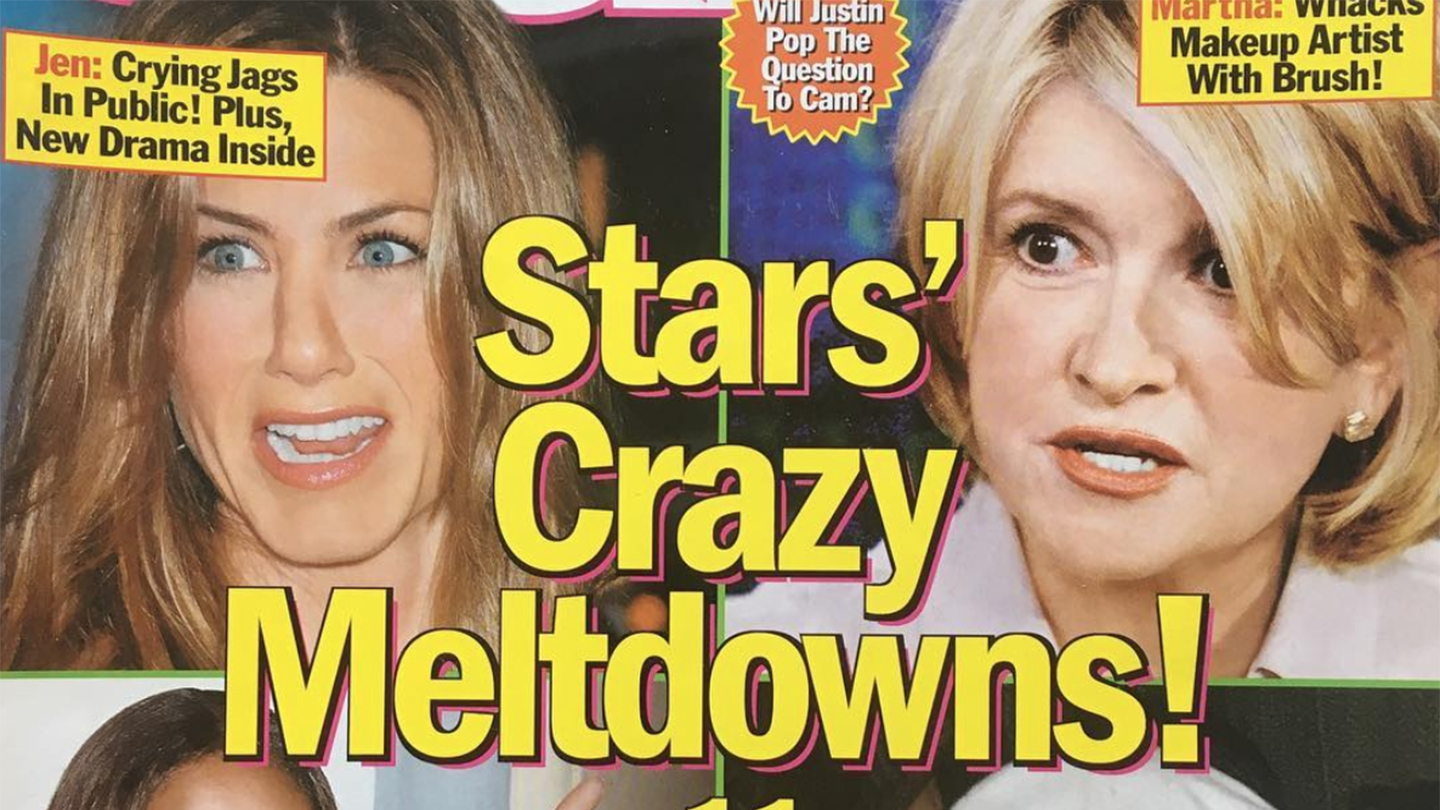

Open up your Instagram timeline and you’ll immediately be greeted by e-kid micro- and nano-influencers clad in Juicy Couture tracksuits and Dior saddle bags. The e-kids glorify cheesy noughties fashion trends, Motorola Razr flip phones, and treat Tumblr page “pop culture died in 2009” as their Holy Writ, glamourising a number of problematic noughties tabloid headlines for the flex. It’s not unusual to see a posts of Us Weekly or People magazine issues from the noughties which chronicled a celebrity’s mental ‘breakdowns’, diet struggles and body issues, or drunken nights out. The caption “iconic” normally accompanies. Yet, in the height of our current Y2K fashion revival, many of these nostalgic teens seem to be remembering the noughties through the decade’s trademark tiny rose tinted glasses, and brushing off a number of social and political issues with each ill-thought-out tribute.

When we think about noughties pop culture, our mind immediately jumps to the tabloid ‘scandals’ that dominated the era. We remember Janet’s nip slip, Britney’s umbrella-gate and TMZ’s dark obsession with Nicole Richie’s fluctuating weight. But because each tabloid saga and the accompanying paparazzi pictures are so ubiquitous, it’s all too easy to forget that the stories we’re celebrating with nostalgic posts happened to real women, famous or not. As paparazzi and celebrity tabloid culture reached its peak in the 2000s, the ‘entertainment’ aspect of each female celebrity’s downfall had us all gripped. It encouraged us to take part in their public degradation, inviting us to set fire to the stake.

It’s hard to imagine now, just 19 (19!) years on, but before the days of Twitter rants and YouTube apology videos, an unforgiving tabloid press entirely controlled the narratives of female socialites, actresses, and popstars alike. It was a time where Us Weekly stoked a public obsession with Lindsay Lohan’s alcoholism, while paparazzi photographers pressed in so tightly on Britney Spears that she almost dropped her infant son (which itself, obviously, became a story). Despite what may be presented on nostalgic noughties Instagram accounts, the predominant marker of 2000s pop culture was not velour tracksuits or Ugg boots, it was an invasive, and deeply misogynistic media.

“Celebrity narratives and pop culture help us define who we are and what matters to us as a society,” says Sady Doyle, author of Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear… And Why. Sady explains partly why we were so obsessed with these narratives in the noughties, and why they still appear as a visceral, and to some, darkly appealing, marker of the era today. “These stories provide a way for people to collectively litigate human behaviour; to decide what a ‘good person’ and ‘bad person’ looks like, which is particularly potent for women, who are always being scrutinised based on a much higher and crueler set of standards. Most of us have had a bad breakup, or gotten messy drunk, or been depressed, or had casual sex — but by treating those things as uniquely horrible, unlovable, unfeminine defects, we scare ‘normal’ women into feeling ashamed of themselves, and keeping quiet about their experiences.”

The depiction of female celebrities’ lives through noughties pop culture played a didactic role in our lives. Before the age of social media, where celebrities are more accessible than ever before, and a famous woman can appeal to her fans directly over emotional Instagram lives, or show their personality through tongue-in-cheek tweets, the tabloid cult of the celebrity were the lens through which we learned what was acceptable female behaviour, and what wasn’t.

Now almost two decades on, it’s easy to see that these noughties tabloids have aged about as gracefully as Little Britain, and yet, they remain idolised among a section of primarily young, primarily female users online. Conversely, as the rise of social media has enabled us to empathise with celebrities as real people and learn about social issues, it’s also on social media that a subculture of Gen Z’s have been romanticising Y2K pop culture and the noughties tabloids which attacked them. Despite being the wokest generation when it comes to gender, LGBTQ issues and environmental awareness, many of us are still romanticising a problematic era. Imogen Wilson, a 20-year-old Londoner who frequently posts to Tumblr and Instagram about the 00s, says it’s a “grey era”.

“Dressing in these pieces takes me back to the influences from my youth, the pop culture and music of the time,” Imogen tells i-D. “There’s a real sense of nostalgia associated with a lot of the clothes and brands I choose to wear now. Admittedly, I don’t associate the fashion of the 2000s with the deeper rooted issues of the time. I treat my love for fashion as a separate matter, mainly because I was so young during the noughties that I wasn’t aware of it”.

Ultimately, does romanticising the trends and pop culture moments of the 00s make you less cognisant of the issues that era had? Andi Zeisler, Co-founder and Director of feminist media outlet, Bitch Media, argues: “It’s okay to like a thing and then grow up and realise that there were things in it that you missed because you didn’t have the language, ideas or vocabulary, and that’s totally normal. Just because we’re living in a time where people’s consciousness has been raised, doesn’t mean you have to disembowel them and act like you’re dropping a truth bomb on everyone. It’s okay to leave that stuff in the past.”

And perhaps these examples should be left in the past and we can carry on ironically using Motorola ringtones and go on our merry way, but not without putting a microscope on how it can set an example for the future of pop culture, first.

Eleven years on from Britney’s well publicised mental health crisis, another young popstar, who began as a child star, was in a similar position. Demi Lovato, however, was not labelled as a “trainwreck” by the tabloid press or on social media. Instead, she was lauded for her honesty and contribution to reducing the stigma around mental health issues. Earlier this year, when Britney herself revealed she had checked into a mental health facility, the outpouring of sympathy — not ridicule — was so palpable Britney had to respectfully ask for privacy from devoted fans. No longer was “leave Britney alone” an internet joke. Instead we actually did want to encourage leaving her alone to heal. With societal progression and repossession of narratives through social media, Lovato has been able to dominate campaigns surrounding mental health positivity, which arguably may not have been feasible a decade ago.

If the wildly popular Tumblr pop culture died in 2009 has it right, and 2009 is really when we went through a complete pop culture overhaul, then maybe that’s for the best. 2019 is not a perfect world by far, but it’s not a leap to speculate that if similarly messy exposé headlines were to be published today, the general public would react with much more empathy than they did in the noughties, pointing fingers at the tabloid press rather than the subjects themselves. It’s not a crime to be nostalgic over the messy era that was the noughties, but we should still remember that it wasn’t all sunshine and flip phones. It’s also the era that gave us constant misogyny in the tabloids (and Nu Rave). If we want to remember the noughties, we need to remember it warts and all.