Shortly after meeting congressman and activist John Lewis during the Civil Rights Era, photographer Danny Lyon shot a four-minute short film soundtracked by the gospel song “This Little Light of Mine.” Last week Lewis, the last surviving “Big Six” civil rights activist and leader of the recent House floor sit-in over gun control, explained the lasting significance of that song during a talk with Lyon at the Whitney Museum, which is currently showing a massive retrospective of Lyon’s photographs. “It was so fitting that so many years ago these young girls, and others all across the South and all across America, were singing ‘This Little Light of Mine,’ he said. “Last night on Capitol Hill, more than 2000 people sang ‘This Little Light of Mine.'”

Lewis was describing a rally at the Capitol for the gun control campaign Disarm Hate, which recently united anti-gun activists with LGBTQ groups to strengthen its all-important message. As events over the last few weeks have proven — including the murder of 49 people at a gay club in Orlando and the deaths of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and several police officers in Dallas — political and racial tensions are intensifying in horrifying ways that have given a sad new relevance to Lyon’s photography. During the Civil Rights Era Lyon documented the freedom rides that were organized by 13 black and white civil rights workers to protest segregation on interstate busses in 1961 — the same year President Barack Obama was born. “What was he doing? Nothing!” they joke. “He was lying around in Hawaii!”

Lyon is now 74, exactly the same age as Bernie Sanders, and in fact one of his first photography gigs was as the student photographer at the University of Chicago, where Sanders was organizing sit-ins to protest segregation. Earlier this year Lyon took to his blog to defend Sanders after news outlets disputed the authenticity of some found viral photographs of his early civil rights work, including one of him being arrested in 1963. “I photographed Bernie a second time after he got a haircut, as he appeared next to the noble laureate and chancellor Dr. George Beadle,” he wrote. “Time magazine is now claiming it is not Bernie in the picture but someone else. It is Bernie, and it is proof of his very early dedication to justice for African Americans.” The affirmation comes from a fairly non-biased source — Lyon admits to Lewis that he was never close friends with Sanders, rather finding him quite boring, much to the predictable horror of the liberal audience at the Whitney. “John, do you know that everyone here is a Bernie Sanders supporter?” he joked to his friend at the start of their conversation.

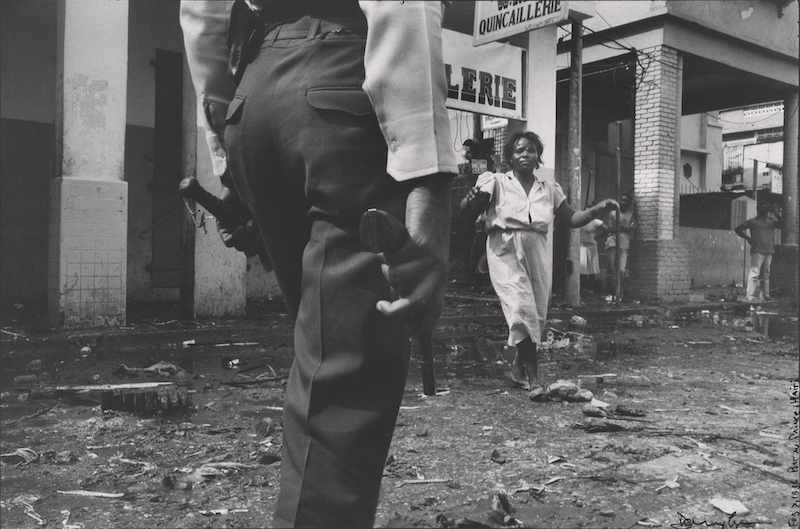

But Lyon’s real contribution to history is the photos he took of cops clashing with protesters at rallies and sit-ins. Heavily armed, stony-faced members of the National Guard arrest non-violent activists both black and white, and guns and tear gas feature prominently. Many of them look like they could have been taken at the marches taking place in Baltimore and Baton Rouge to protest police brutality. Lyon’s civil rights photography also emphasizes the danger and importance of filming instances of police violence in the age of smartphones and social media — a point which was made extremely clear by the incredibly brave and resilient Diamond Reynolds, who posted a Facebook video of the traumatizing aftermath of her boyfriend Philando Castile’s murder by a cop in Falcon Heights earlier this month. Lewis noted that before social media (and tiny iPhones) existed it was a lot more dangerous to do this work. “It was very dangerous to be a photographer,” he said. “If you had a camera, a pen, a pad during the freedom rides, when you arrived at the station in Montgomery, they didn’t jump on the white or black freedom riders first. They attacked the reporters and photographers.”

Lyon and Lewis appeared understandably dejected that their work still feels so relevant, but remain optimistic. “When revolutions happen, time is compressed,” said Lyon, reminding the audience that change doesn’t happen overnight. Lewis hopes that America will make the right decision at polling booths. “We’ve got to mobilize and we’ve got to vote like we’ve never voted before,” he said. “America is changing. We should embrace it.”

“Danny Lyon: Message to the Future” runs from June 17 through September 25, 2016 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley

Photograhy Danny Lyon, courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art