This article originally appeared on GARAGE.

If there is anything that film has taught us about female-presenting robots, it’s that they’re stacked. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is the first cinema representation of the fembot (or gynoid), a golden-plated humanoid, who, one can’t help noticing, has metallic round breasts. Two chrome domes.

The ridiculousness of the robot titties was obviously not lost on the designers, who circled the breasts of the robot with an art deco-inspired ring, as if to symbolize that this part was not an essential component but a decorative one. Decorative objects, Jacques Derrida noted in his analysis of Immanuel Kant’s aesthetics in The Parergon, are theoretically not part of the object; the decorative is there only for our pleasure, while, at the same time, by framing the object, the decorative defines its essence. Just as certain domestic appliances, from hair dryers to headphones, have aerodynamic decoration to indicate their closeness to air and wind despite not moving at all, the round bosoms of the fembot define the robot as female despite having no function for the machine.

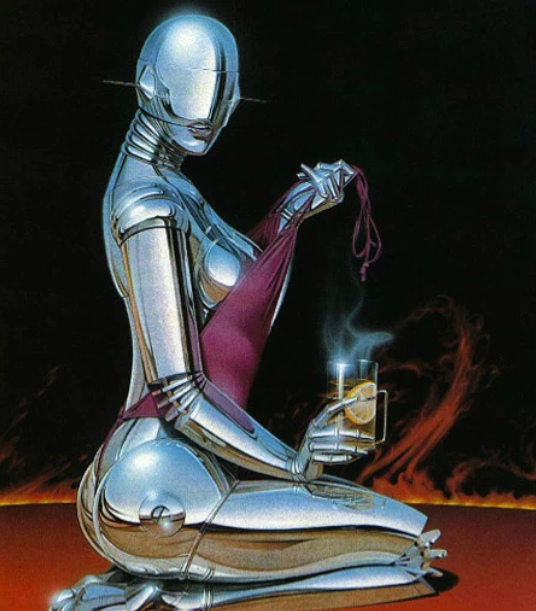

Of course, with fembots, feminization may begin with the titty, but it doesn’t end with the titty. Decoration is the go-to method to express the idea of a gendered machine, and the female robot is decorated with long, fake lashes and curves that are sinuous and pleasing. Sometimes fembots wear clothing, and their sartorial choices tend to read “retro,” with ’50s-inspired dresses or skirts and heels (thinkThe Stepford Wives, Ex Machina, Rachel from Blade Runner, and Dot Matrix’s chrome skirt in Spaceballs).

Even when a fembot has no explicit sexual function, like the crude coffee-serving robot named “Sweetheart” made by American sculptor Clayton Bailey, the robot tits are there, out to here, defined in such an exaggerated way that we almost dissociate the robots tits from reality. The breast loses its function of nutrition and connection with the child, as well as its softness. Here, the breast stands for itself, as a pleasurable characteristic for someone else, someone who is a human and not even a robot, completely separated from any of the reasons it has developed in our biology. When a controversy emerged around Sweetheart, Clayton’s defense was, “This is my idea of what a pretty female robot should look like.”