“You guys know my fucking influences,” Kanye West spat at Vogue following his Yeezy Season 1 presentation back in February. “You see Raf Simons right there, you see Helmut, you see Margiela, you see Vanessa [Beecroft], you see Katharine Hamnett. It’s blatantly right there.” He’s right. His oversized visions of utilitarian ease build on the bombers and body stockings that have come before. But this season, one of West’s influences was, in fact, blatantly right there. Sitting in the rapper’s star studded front row, British designer Katharine Hamnett moved almost anonymously through a constellation of Kardashians.

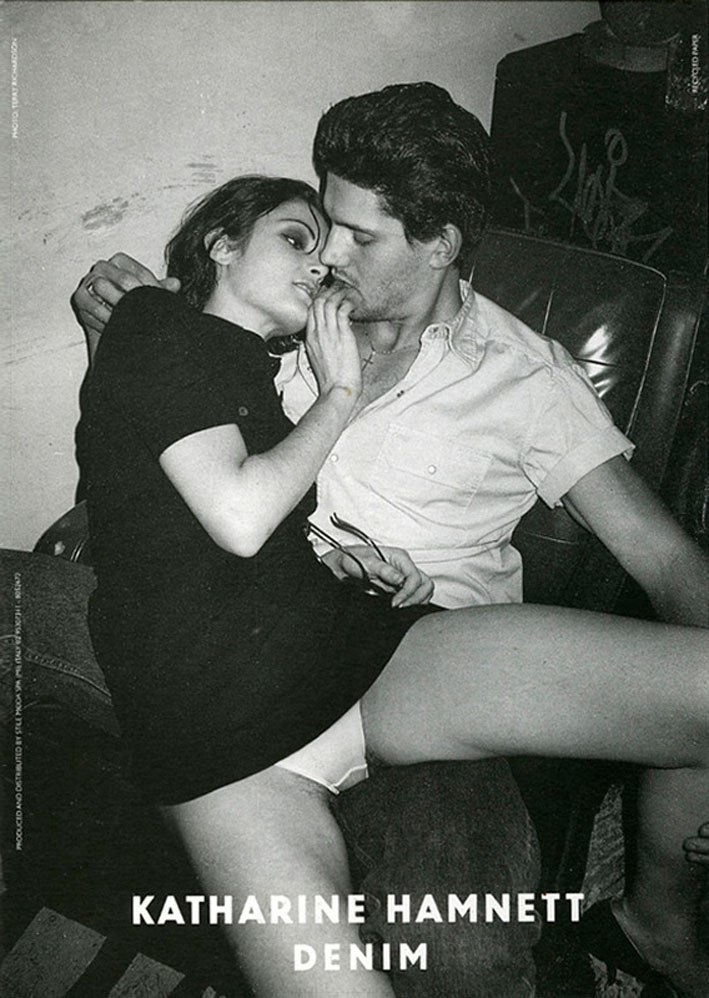

It’s been confirmed that to some unconfirmed extent, Katharine opened up her archive for Kanye’s highly anticipated sophomore season. While there are certainly traces of Hamnett’s mid-90s pocket proportions and rich caramel color stories found in West’s work, the designer can’t — or won’t — reveal anything about her collaboration with the rapper (outside of assuring “he is a really lovely guy,” when we speak on the phone). But perhaps that silence isn’t such a bad thing. For 25 years, Hamnett has been fighting to get the fashion industry talking about something other than fame: its true environmental and ethical costs.

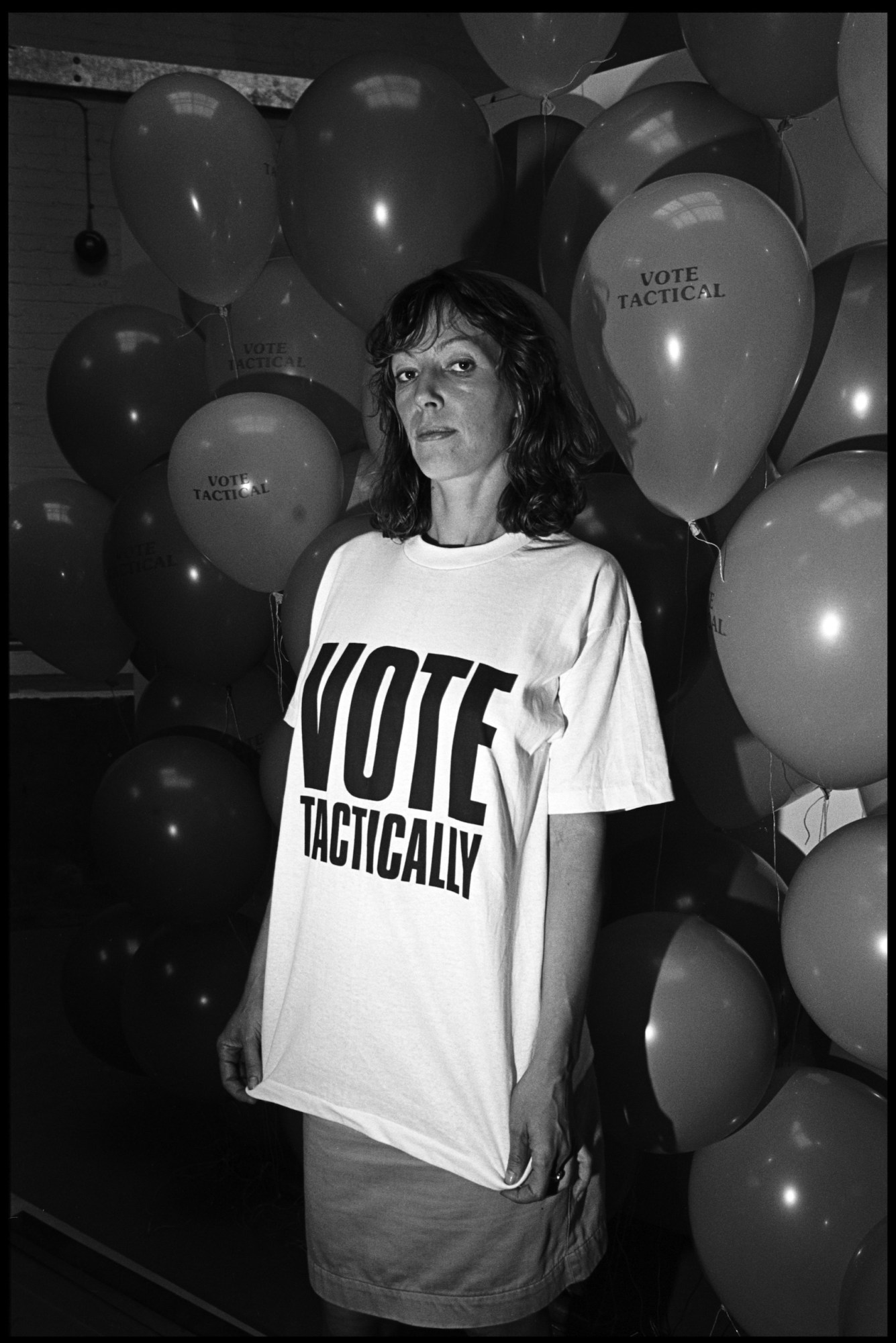

After completing her studies at Central St Martins and finding success with collaborative line Tuttabankem, Hamnett launched her launched her eponymous label in 79. Things exploded. “We were just doubling our turnover every season; we were stocked in 700 shops in about 40 countries,” she said. In 83, she produced a series of bold block slogan t-shirts bearing socially conscious messages like “Worldwide Nuclear Ban Now,” “Preserve the Rainforests,” and “Choose Life,” — a Buddhist-inspired call-to-action that was frustratingly later appropriated by the anti-abortion movement.

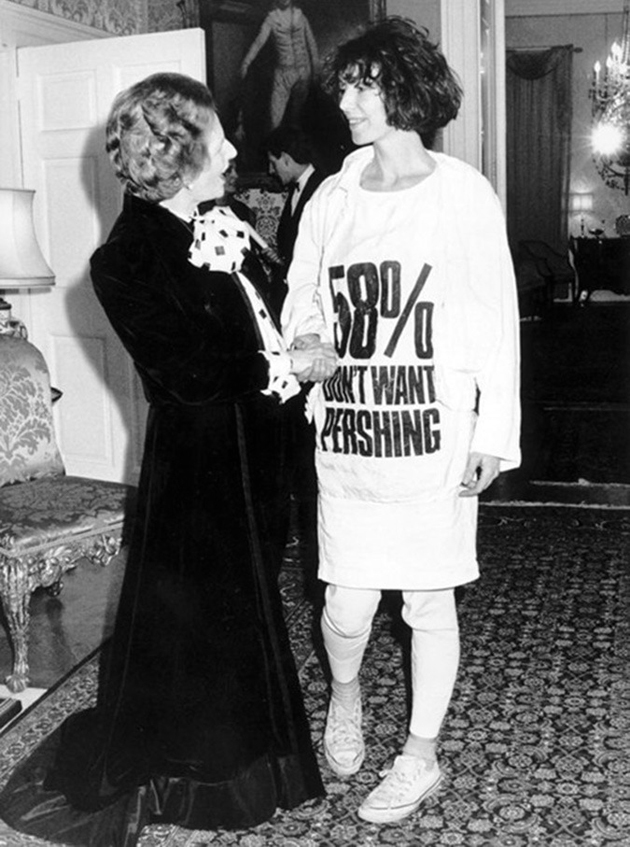

The following year, she was awarded Designer of the Year by the British Fashion Council. This esteem famously landed her at a Downing St cocktail party, shaking Margaret Thatcher’s hand in an anti-missile slogan shirt the Iron Lady never saw coming — an image that was later cheekily spoofed by Georgia May Jagger and Alexander Wang in Harper’s Bazaar. Somewhere in between those moments, Hamnett’s stateside pupil called out one of his generation’s most controversial leaders, George W. Bush — only live on national television. “T-shirts are great, but they don’t change anything, really,” Hamnett said. “Unless you take constructive action in other areas of your life, just wearing a t-shirt actually isn’t going to do anything.”

As the 90s approached, Hamnett commissioned an independent report into her company’s manufacturing practices, “just to make sure that I wasn’t doing anything wrong” by her adopted Buddhist principles of right thinking, right living, and right working. “When the information came back that 10,000 people a year are dying from the clothing industry’s reliance on cotton agriculture, pesticide poisoning — this endless litany of environmental and social injustice, really — far from living the fashion ‘dream,’ I found myself in a living nightmare,” she said. “Either you’re going to block your ears to all of this injustice, or try and do something about it. I chose the latter and I’ve been battling ever since.”

In her tireless efforts to overhaul exploitative production and consumption practices from within, Hamnett has penned pieces for The Guardian, staged protests alongside fellow eco-punk Vivienne Westwood, even surprised one of her suppliers with a Channel 4 news team when he was late with a deposit for organic farmers. Her slogan shirts have evolved to represent the causes she campaigns tirelessly for, but more importantly, so have her manufacturing methods.

After embarking on a trip to West Africa with Oxfam in 03 to expose the true cost of cotton agriculture, Hamnett has made it her mission to educate others about the process’s devestating impacts on the ecosystem, as well as about “the people working under conditions of slavery and starvation.” Conventional cotton production requires a disproportionate amount of harmful pesticides that not only contaminate ground water, but become trapped in the atmosphere as greenhouse gasses. Farmers are often required to purchase these pesticides in order to cultivate their crops, and the material costs of these harmful chemicals effectively bankrupt them. In regions that rely heavily on cotton exports, like Mali, that often means cyclical poverty. “In India, there have been 250,000 farmer suicides in five years due to these pesticide debts,” Hamnett said.

About a decade ago, the designer tore up most of her licensing deals and eventually relaunched her entire brand under stricter guidelines — including a full commitment to fairly farmed organic cotton. “We’ve seen huge technological progress being made in the last 25 years. It’s possible to produce fashion we actually like sustainably so it doesn’t look ‘eco,'” Hamnett said, “but it needs to be done organically.” Without rising pesticide costs, “farmers can earn a livable wage, feed and clothe their families, educate their children, and access healthcare services, which is not the case right now.”

But in many ways, Hamnett’s biggest battle hasn’t been with any organization or government agency; it’s been with her peers in fashion. “I’ve battled with many people I was working with to try and convert them to making clothes sustainably and in most cases, failed.” For decades, her calls for sustainable sourcing and humane labor standards fell on deaf industry ears. But as the paradigm begins to shift, Hamnett is hopeful that today’s consumers will challenge a new generation of designers supporting ethical production more seriously than their established elders. “Decide how you want your money spent,” she encouraged. “Write to the brands you love and tell them that you want to buy their stuff, but that you only want it made sustainably. Fashion is greedy, so take it to the profit margin. You really do have the power.”

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography David Corio/Redferns