To speak your mental health struggles into a reality beyond yourself is scary at the best of times, but when cultural constructs of ‘who’ is worthy of emotional anguish, ‘who’ is capable of feeling pain come into play, this pressure builds up to bursting point. This is the intersection of race and gender that complicates the already existing stigmas and stereotypes surrounding mental illness, and the resulting whitewashing of discussions. We brought together four leading mental health advocates exploring these intersections: Imade Nibokun (author of Depressed While Black), Dior Vargas (People of Colour & Mental Illness photo project and White House Champion of Change for Disability Advocacy), Bassey Ikpi (creator of the Siwe Project) and Lisa Lee (co-founder of Thick Dumpling Skin) to create a conversation on family, faith, first generation angst and why the myth that mental illness is ‘a white person thing’ seriously needs to stop.

How do your experiences of faith, family, race, class and culture shape and complicate your mental health advocacy?

Imade: All of these experiences cause me to ask questions when most people may take something on a surface level. I’m a Christian, but I’ve been victimised by people who believed depression was a sign of my spiritual insufficiency. I’ve internalised that message and deprived myself of mental health resources. I’m both the problem and the solution.

Dior: I wanted to focus on my community when it comes to my work. Race and class has an impact on the type of access and support you get when it comes to health in general. In addition, culture affects what type of treatment you seek when it comes to mental health. Having these experiences have shaped my advocacy because I have the lived experiences of how they impact one’s experience with mental health and the mental health system.

Bassey: My father taught me that everything we do in this family not only affects our immediate family but also my home country, my state, my village, my extended family and so forth. In most immigrant households, it’s taught to place pressure to encourage excellence, and it was for mine as well, however, it supported my anxiety issues when I was younger. It centred me as the root cause of problems elsewhere good and bad.

Lisa: Our experiences are a part of our identity, so when it comes to mental health, all of those things intersect and are interdependent. Thick Dumpling Skin was born precisely out of the need to consider all of those experiences together because we weren’t seeing our stories out there. We value our place in the work that we do because we were not seeing our stories out there.

How does the intersection of race and gender impact and influence the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness?

Imade: There is a flippant attitude towards the suffering of black women. We are often portrayed as better off than black men, while being oppressed by black men. It is very hard to get people to understand how depressed you are when you’re not in jail or dead like “those black men.” Not being seen can make you hurt yourself more to be seen. So sometimes as black women, our self-harm can look like being a mule for our family to prove that we are deserving of love and support. When we normalise that cycle of self-harm, it can be difficult for anyone to say that we are depressed or anxious.

Dior: When it comes to race, individuals are usually more severely diagnosed. When coupling that with gender, it makes it more difficult because mental health professionals don’t match the community they’re serving so it makes it difficult for people to get culturally competent care.

Bassey: As a Black cishet woman, our mental health is often overlooked. Black women are attacked emotionally by the stereotypes forced upon us. We are accused of having bad attitudes, being too loud. We are told to be “strong, black women” and that phrase is killing us. Going back to religion, we are taught that the test of true faith is to endure suffering until you’re rewarded in heaven. So as a result, many are taught to turn to faith instead of doctors. We are often misdiagnosed by not being diagnosed. Our very real feelings about what we go through are being turned around and dismissed as insignificant.

This happens to women at all turns, I mean the term “hysteria” was used to dismiss and silence women medically. Now add stereotypes about Black people to that equation and the dismissal and silencing comes with an inability to acknowledge that Black women hurt. And not only do they hurt but that hurt is wrapped up in cultural expectations that we often take on ourselves. I call it “strong black womaning yourself to death.”

Lisa: I think it’s incredibly important that we need to have (diverse) doctors who are embedded in different cultures and can understand the complexities when it comes to treatment. For example, you can’t begin to treat something when a lot of people from the patient’s community don’t even recognise that thing as a serious problem.

Do you feel there is a specific pressure for those of us who are first generation migrants to so called ‘Western’ countries, an expectation to ‘succeed’ coupled by the issue of navigating medical systems and cultural ideas that may be unfamiliar to elders?

Bassey: In short: Yes. First generation immigrants are the guinea pigs. The quest to be successful at all cost is a looming cloud. Your parents literally left all that they know to give you a better life. It would be disingenuous to say that it didn’t come with pressures. To this day, I feel like a disappointment even if I’ve never been told that.

Dior: The experience of border culture, when you are living within two cultures where one is very collectivistic while the other is very individualistic, has an important role on why Latina teens in the US have one of the highest attempted suicide rates. We are under a lot of pressure to succeed but definitions of success can vary based on one’s culture which makes the process all the more stressful.

Lisa: For Asian Americans, yes absolutely there is the model minority stereotype that we’re dealing with — both externally, and even internally amongst our own community. We are expected to find the “American Dream” through sheer hard work so when there are issues that deserve medical attention a lot of us treat the issue as if we can simply “work” our way through it. Language barrier and the fear of an unknown medical industry come into play as well.

Why do you think the hurtful stereotype that mental health issues are a ‘white people thing’ came about and how can we challenge that?

Bassey: Lack of transparency. There is at least one person in every household who struggles with with a mental health issue. But people of colour don’t have the luxury of not doing well in school or at work. The idea that it is a rich person thing or a ‘white people thing’ is because so many of us are shamed into silence or feel that it’s making excuses for laziness. It’s not something that we can see therefore it must be for “them” not us. I think a lot of immigrants are told that suffering is part of life. It’s customary to work 20-hour days to support your family or finish your degree to make a better life for your family. That isn’t healthy. That isn’t life.

Imade: In my talks, I often discuss the legacy of Dr. Samuel Cartwright, who was a pro-slavery physician who said slaves who ran away are mentally ill. He said that in order to “treat” this mental illness, these slaves should be whipped. We see this today. People of colour who pursue liberation are considered crazy. They are told they should continue their cycle of self-harm because they are not worthy of mental freedom. Historically, it is more accurate to say that people of colour, Africans specifically, invented mental health treatment. Egypt had cutting edge physicians who diagnosed illness through dream analysis. The true narrative was lost due to the dehumanisation of people of colour across the world. That dehumanisation includes erasing their mental complexity. We, as people of colour, need to reclaim our minds as a space of exploration.

Dior: People of colour have undergone so many struggles that the concept of going to see a therapist or to admit to having a mental illness is viewed as a weakness and brings shame to an otherwise resilient, survivor identified community. The way to challenge this is to have initiatives that show that individuals, no matter what background, can experience mental health conditions and that it’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Lisa: We have to keep sharing our stories and our experiences so that we are first and foremost, acknowledging that a different reality exists. Then we can begin to treat it.

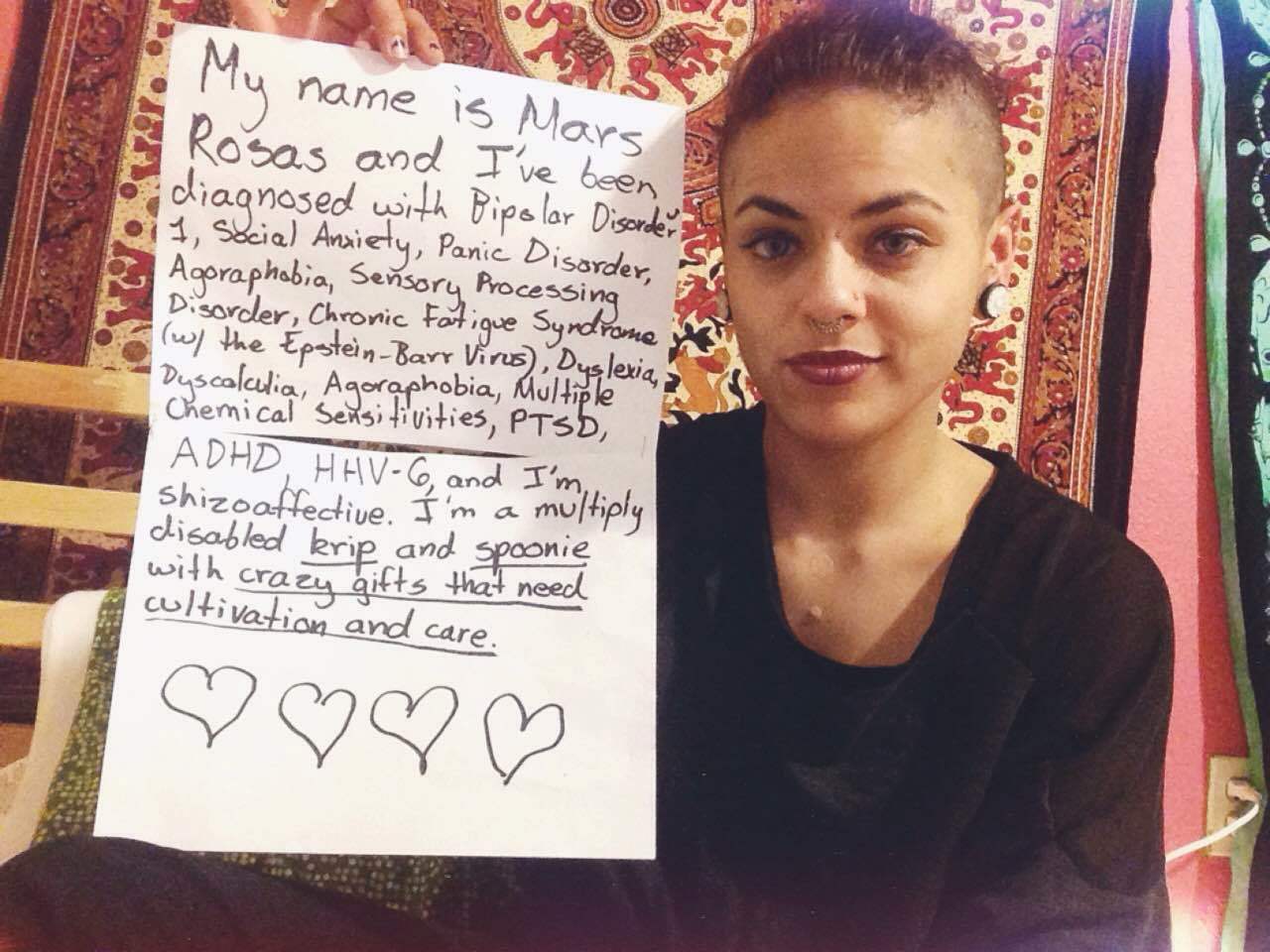

From Dior Vargas’ People of Color & Mental Illness Photo Project

What resources would you recommend to a woman of colour who feels she may be struggling with her mental health?

Dior: There are resources specifically for women of colour such as: Tessera Collective, Brown Sisters Speak, and No More Martyrs. There are also the following blogs: Depressed While Black, Black Girl + Mental Health.

Imade: For the UK, with the emergence of Recovr, there is a chance for more black people to find mental health professionals that address their unique needs.

Despite the whitewashing of mental health advocacy the history of women of colour writing and advocating for their wellbeing is incredibly rich. Who inspires you, both historically and within the present day?

Imade: Bassey inspires me. Nigerian culture is in many ways, ground zero for mental health stigma. And yet she creates a path in the darkness by inspiring people to get the help they need. Dior Vargas inspires me. To see her reclaim spaces (like the White House!) for the mental healing of Latina women, and all people of colour is mind blowing. I keep telling her that she made a template for what I’m doing now. My goal is to follow in her footsteps. Meri Nana-Ama Danquah, author of Willow Weep For Me, is my hero because writing a first hand account of depression and centring black women pain is a revolutionary act. Ida B. Wells is my hero because she combined journalism with activism. She knew the power of her pen. I hope to wield mines just half as good as her’s.

Dior: There are many women of colour advocating for themselves, they make me want to do better and I don’t feel alone in this fight. Some women are A’Driane Nieves, Imade Nibokun (Depressed While Black), Nadia Richardson, Erika L. Sanchez, Mimi Khuc (Asian Mental Health Tarot), Gayathri Ramprasad (ASHA International), Nikki Webber Allen (I Live For…), Emily Wu Truong, Jessica Gimeno (Fashionably Ill), and many more.

Bassey: My most significant and life changing connection is with my friend and mentor, Nana-Ama Danquah. Willow Weep For me was one of the first (and I believe the only) memoir written about depression from the perspective of not only a Black woman, but an African woman, who moved to the United States at a very young age. Her journey and story could have been written for me and by me. It was like a glimpse into my future if I were able to give myself permission to know this thing about me. It is the book that defined the experience and gave me language and voice. It saved my life.

Lisa: Historically, I am inspired by the strength of Grace Lee Boggs. Presently, I am deeply grateful to bell hooks; her writings have helped me through some mental turmoil. In addition, I am also surrounded by mentors and friends who are such amazing women of color that they defy and re-define what it means to be a woman for me all the time.

Credits

Text Bethany Rose Lamont

Image via npr.org and diorvargas.com