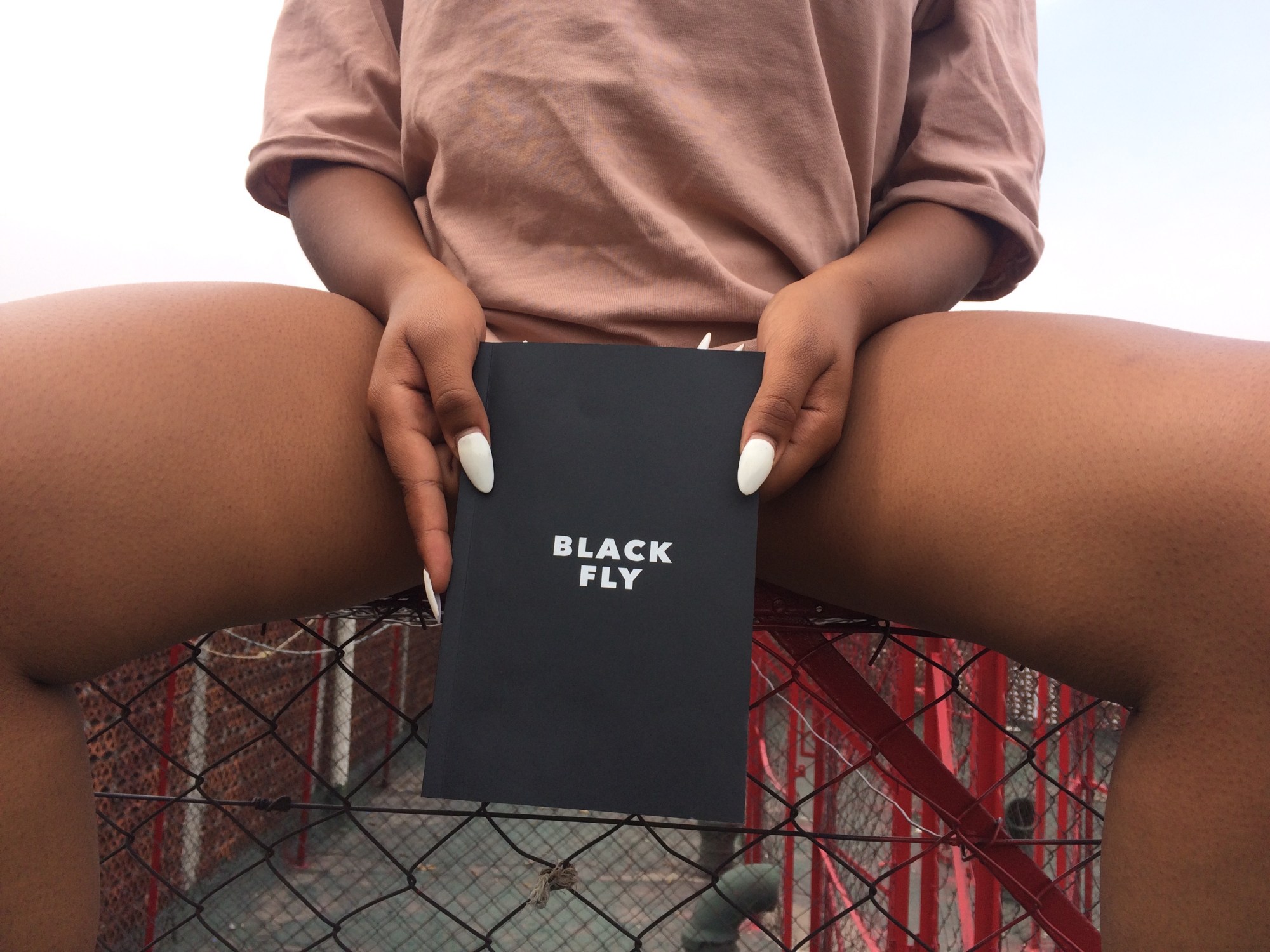

Supportive words of encouragement jump from the pages of the Black Fly zine; a publication devoted to exploring the sexual health of people of colour. It’s about as far as you can get from the grey hostility and questionable design of the scientific pamphlets that litter sexual health clinics. Founded by Ella Frost and Nana Adae-Amoakoh, the zine offers a new art-driven approach to exploring those marginalised by the traditional approach.

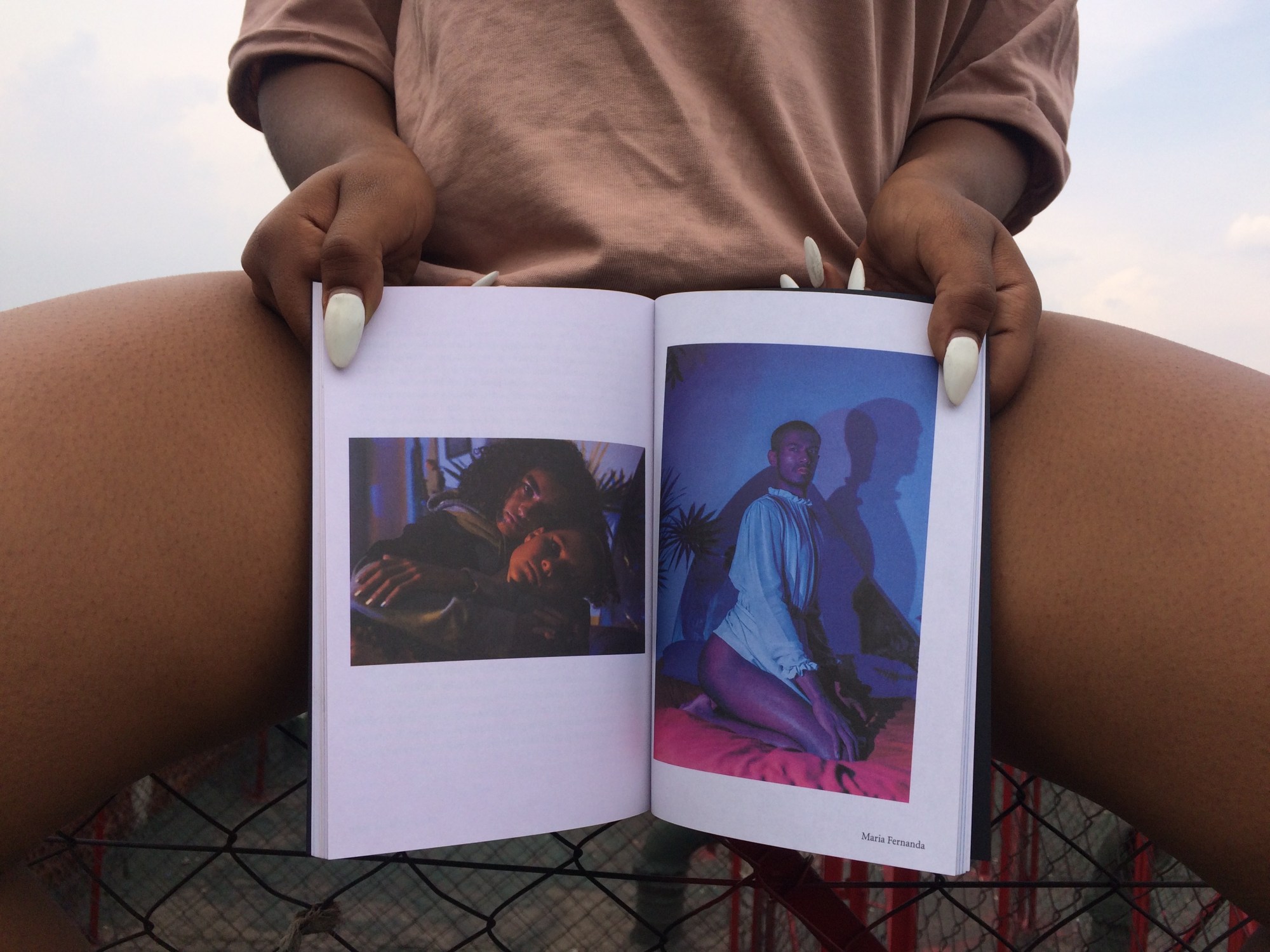

After working with teenage survivors of sexual abuse, Nana noted that her “caseload was overwhelmingly black and brown girls”. Despite this, there was no intersectional understanding in place, which was “contributing to how black and brown communities are made vulnerable”. At the same time, Ella, a visual artist currently living in Mexico City, was thinking of developing a zine for people of colour that examined their identities in connection with their sexual health. Though the magic of the internet they found each other, and their shared dissatisfaction with the system’s approach to sexual wellbeing led them to envisage a totally new approach. Black Fly zine is a creative and open response to sexual health in which people of colour are invited to offer support and advice to one another, in the form of poetry, essays, illustrations and photography.

People need to hear the stories of emotion as much as, if not more than, the scientific explanations of say, for example, herpes.

Globally people are suffering due to a creeping return to conservatism in healthcare. Placed against this backdrop, it may appear trite to wonder how we can use art to re-imagine mainstream attitudes to sexual health. But the complete lack of formal exploration around how race impacts it is desperately needed, and needs to happen in an open and supportive way.

The first issue shared a global mix of voices from America, Mexico, the UK, Brazil and beyond. Ella and Nana initially kept the submission brief broad. “We really are just facilitators to people sharing their experiences,” says Nana. “People need to hear the stories of emotion as much as, if not more than, the scientific explanations of say, for example, herpes.”

Historically, science has not been used to help communities of colour. Instead it has been twisted by some to bolster racist theories, as well as excluding the specific needs of marginalised people when it comes to accessing services and information. Contextualise that with a recent survey by Georgetown University that showed how black girls are seen as less innocent than their white peers. “Most educational institutions are not meant to serve people of colour, but there are alternatives, we just need to use them and organise,” says Ella.

“One of our motivations for Black Fly is to keep the information accessible, and this isn’t just with regards to cost but also explaining any scientific terms that are used or finding alternatives,” says Nana. “We feel this is one of the obstacles to building knowledge on sexual health — so much of it is shrouded in this academic jargon. I went through the Catholic school system and there were very few conversations around homosexuality. Sex equalled a man penetrating a woman and sex ending when the man ejaculated. In the absence of a condom, the woman falls pregnant. The end. Realising I was queer at 19 was terrifying because the only education I’d had told me I was abnormal.”

With feelings of abnormality often come feeling of stigma and shame. In relation to sexual health, this can mean people tend to worry alone in silence. As people of colour are time and time again left out of mainstream media representations, we find ourselves erased from pop culture representations that may provide some solace to our white counterparts. Black Fly transforms what could otherwise be a source of shame into something people want to own.

Art can become a platform for communities who have been marginalised by ‘scientific fact’ to change the usual narrative, to point out its limitations.

Following on from the positive reception of the zine — people from around the world have been in touch wanting to be a part of it — and a workshop in collaboration with gal-dem at the Victoria & Albert, Ella and Nana joined forces with Anonymous Gallery in Mexico City and various Latinx artists. One of the artists, Lia Garcia, got the audience to share their experiences of trauma by writing it on their bodies. When speaking to the artists involved about why they believe art can help us re-think our ideas surrounding sexual health, performance artist Jenny Granado responded, “There are bodies that don’t matter, those bodies are generally poor, indigenous, black, migrants, women, trans. Criminalisation of the life of those bodies has been already a long and colonial process where only few people get benefits. Art, in broad strokes, is a tool for awareness, but also for information, and in that way, it is an artist’s job to point out the structures of oppression.”

Art can become a platform for communities who have been marginalised by ‘scientific fact’ to change the usual narrative, to point out its limitations. However, as Ella rightfully notes, ‘I am unsure about art in and of itself helping a situation, which is embedded in economics, access to wealth, education and healthcare.” Yet, one thing is clear, Black Fly and the work of other artists involved demonstrate how creativity, led by those affected, can help us listen and shape how we understand the traditional conceptions of sexual health, and who should be seen as an authority surrounding that, in the future.