Fab 5 Freddy is a hip-hop pioneer who began working in late 70s New York. He was instrumental in bringing together young practitioners of street culture from Brooklyn and the Bronx with the downtown art and punk scenes.

Olafur Eliasson is also a pioneer, you probably know him as one of the most feted and celebrated artists working today. Creator of grand environmental and architectural installations. But maybe you didn’t know that before he went to art school he spent his teenage years doing graffiti and breakdancing around Scandinavia.

Ahead of Olafur Eliasson’s retrospective, opening at the Tate Modern this week, Fab 5 Freddy and Olafur sat down to discuss street culture, film and the diversity of cultural expression in Europe and America in the 80s.

Olafur Eliasson: As a teenager, I was not just interested in street culture but obsessed by it, and your movie Wild Style had a major impact on me when I saw it. There has been a tendency to criminalise the presence of Black kids on the streets in order to prevent the idea of a community defined by street culture and collective activity on the street. How did you experience this in the early era of street culture?

Fred Brathwaite, aka Fab 5 Freddy: When I was a young teenager back in the 1970s in New York City, very few had anything positive to say about the graffiti art we were making, the breakdancing or the rap music. Poor white kids in New York were also doing graffiti and similar things, but because of racism, it was the Blacks and Latinos who were criminalised constantly in the local press. No one saw anything positive in what they were doing. That’s where the idea for Wild Style came from. I wanted people to see that we were artists, that we were expressing ourselves in new ways — that there was an important creative movement happening.

The film successfully documented not just a very creative culture with a strong sense of artistic content, but also its resilience, its conviction. It’s clear to everyone now that art history was being made. Where did this incredible resilience and self-confidence come from?

I saw a documentary recently called Shake the Dust from 2014. It looks at breakdancing in a lot of different places, like war-torn areas of the Middle East, Africa, and in really poor places in South America. These kids are so poor that they don’t even have cardboard or a piece of old linoleum to breakdance on. The dust billows up when they do their moves. These kids literally have nothing — in some cities all the buildings in their area are bombed out. Still you can feel the energy that they get from doing all these breakdance moves. You can feel the energy and pride. Seeing the film I could recall the original ideas and feelings of the kids that created this stuff in New York City at that particular time in the 1970s. When I see these kids — who have much less than what even the poorest New York kids had back then — I realise that the roots of this are very deep.

The basic idea for doing graffiti and hip-hop music back then was a desire to make people know that we exist — ‘I’m here! I’m somebody!’ — and to claim space: ‘See that building over there, which looks like shit? I’m going to go and paint something brilliant and colourful on it.’ It wasn’t about trying to be rich or famous — it was just to be known in your community and to raise the self-esteem of poor people. It was so simple and basic and pure that I think, like a tree, the roots went down very deep — this was before the hit records, film and TV shows, before street artists began showing in galleries and museums. And it’s amazing to see that it still continues in that real, raw, honest way. It’s more than I could have ever asked for, more than forty years later. I had no idea this scene would be so strong for so long, or that it would spread around the globe.

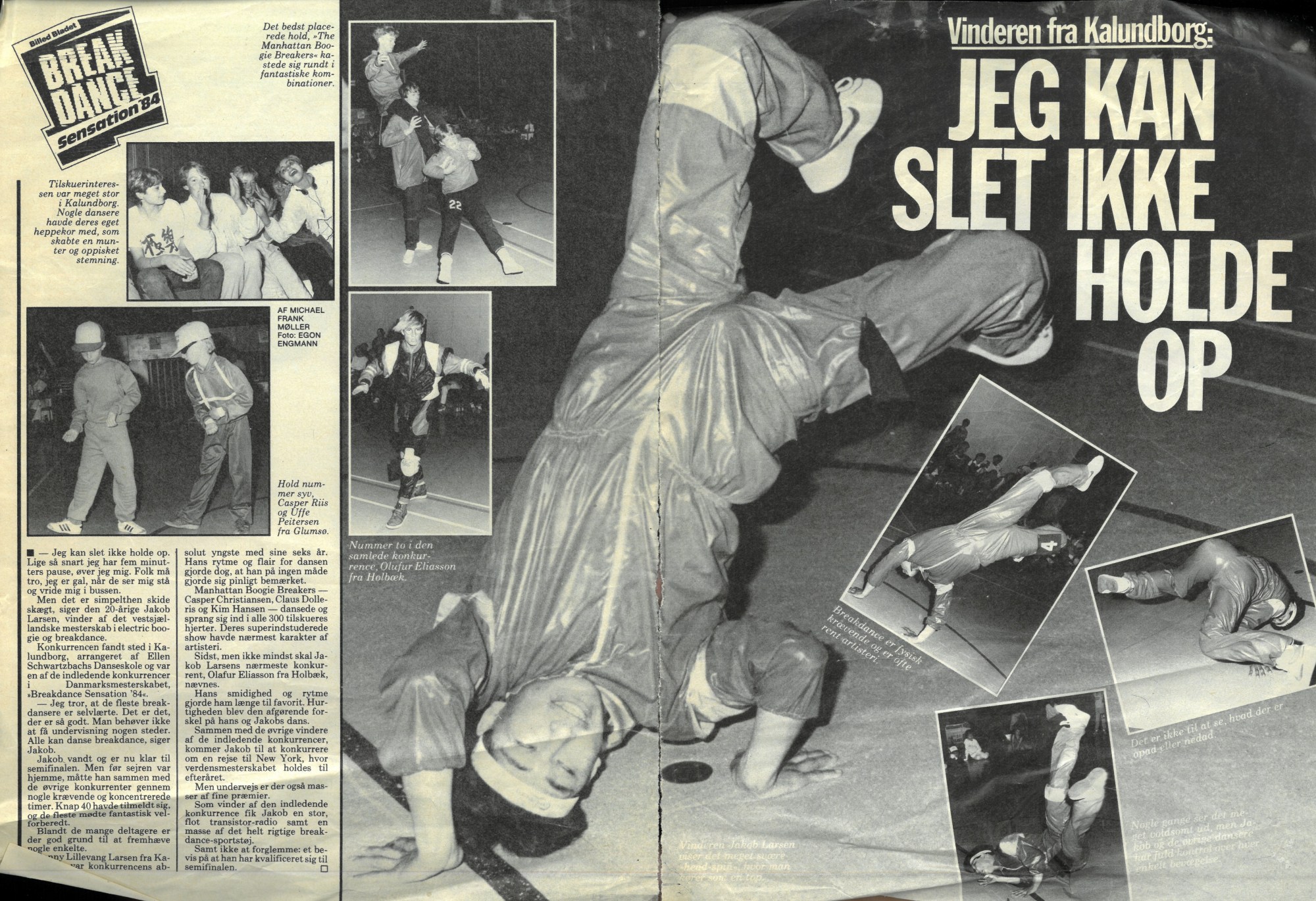

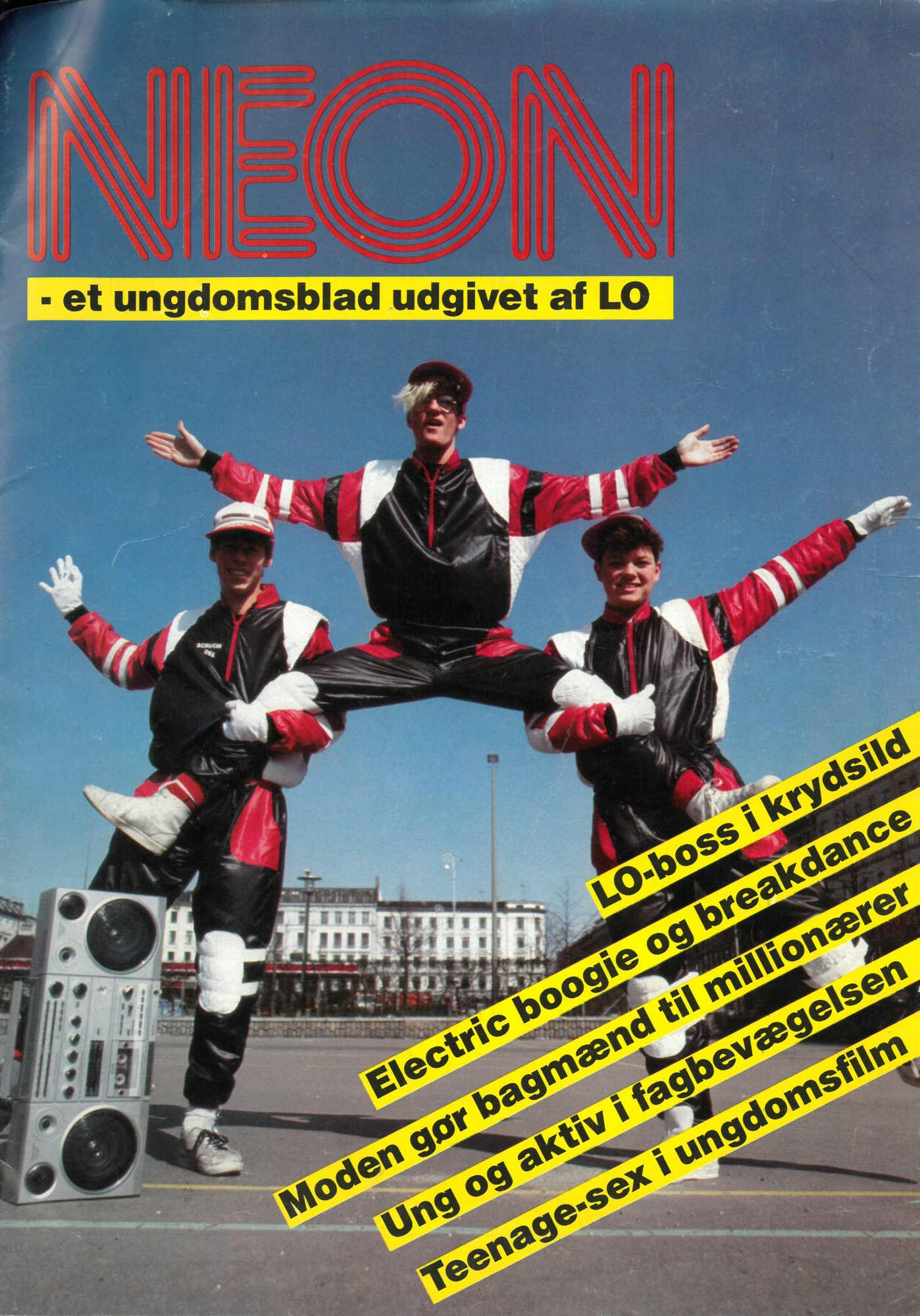

Yeah, street culture still addresses people who are not heard, people who are considered to be on the periphery. And, yes, doing graffiti, doing block parties, doing dance in the streets, is a way to claim not just identity but also space. You know, I grew up in the countryside in Denmark, and on one of my trips to Copenhagen — I think I was probably thirteen or fourteen — I saw some slightly older kids standing in a shop window and moving like robots. It was my first contact with electric boogie. From that day on I couldn’t even take a glass of milk out of the fridge without doing it as if I was a robot. It was the biggest epiphany!

Before cable TV, before the internet, whoever had a VHS tape with some street dance on it was sitting on gold. After about a year I had come to understand that this was something bigger. I familiarised myself with graffiti, which had not yet made its way to Denmark, and became more aware of the whole idea of breakdancing and electric boogie. So there I was, a white kid in rural Denmark, watching the wave coming from where you were. And you were pushing that wave ahead. This was 1983 or 84, when most of my friends were listening to British pop, and I was tuning in to late-night radio stations to hear Kurtis Blow and Herbie Hancock. I would sit there with my tape recorder, pressing record for anything remotely connected to hip-hop.

By the time Wild Style came out, my crew and I had developed some dancing skills. We were by no means established, but we had recognition within that very Scandinavian street-culture scene. Being a dancer and a part of this movement was a very influential part of my youth. Even though we were so far from the Bronx and Harlem, there was something about the resilience of street culture that gave me an opportunity to claim identity, claim my body. It was the start of what later became so important to me – my relation with public space.

I love to hear stories like this! I could never have dreamt that so many different people in so many places would connect with this.

At the time, I also loved drawing. My father was an artist and my mother supported the idea of being an artist a lot, so when I got into the dance scene, it was natural for me to start doing graffiti. Because I was the only kid who could actually draw some semblance of, say, a cow, I quickly defined a small space for myself in what would later evolve into the graffiti scene. You were working as an artist at the time, right? As a painter.

Yeah, I originally wanted to be an architect, then a visual artist. I wanted to paint and have my work shown in galleries and museums, but I could see no clear way to making that happen. I didn’t see many people that looked like me doing anything in the art world. But, like other graffiti artists, I figured out a way to get my name all over the city and paint pictures anywhere I felt I wanted to. In a very rebellious, renegade way, I figured I would be able to find a way into the art world — in that same way Malcolm X famously said, ‘by any means necessary’.

And, again, my motivation for the ideas that became the film Wild Style was to make us look better and change people’s perception of us. I wanted to show that we were artists, not just thugs, gangsters and criminals. I wanted to create the idea that this new culture was all linked. Although not everybody doing graffiti was into hip-hop music, and not everybody into hip-hop was into graffiti or breakdancing, I had this idea to use cinema to create these connections and make our movement look strong and cohesive. I was sure if I could create a story that linked everything, it would make a strong impression to counter the negative narrative. Lee Quiñones, the legendary graffiti artist and my co-conspirator [who played a major role in the film], shared this idea of breaking into the art world and we were determined to make them take a look at our new culture and treat us with respect. I met the filmmaker Charlie Ahearn in 1980 at the Times Square Show, which was sort of our equivalent of the 1913 [groundbreaking modern art exhibition] ‘Armory Show’. Charlie’s twin brother John was a sculptor. Charlie had already made an underground, low-budget, urban kung-fu movie called The Deadly Art of Survival. I pitched him my idea of making a movie about this music and this graffiti painting and breakdancing. So, at the Times Square Show, he said, ‘Let’s work together – come to my office tomorrow.’ The problem was that when we went around to the people who fund independent films, we couldn’t get any money.

Why?

For one thing, because people didn’t believe it. We went in with pictures, cassette tapes, stories, but there had been no media about this, no articles. We said, ‘This is a new important culture developing in New York City – help us make a movie.’ Nobody wanted to give us any money. In fact, the first people to give us money were in Europe. The German television channel ZDF gave us about 25 or 30 thousand dollars — starting money — in exchange for the rights to air the movie on TV. Then Channel 4 in London gave us a similar amount. And with that, we went back to some of the people we’d first met in America and said, ‘Look, the people in Europe are ready to help.’ And that’s how Wild Style got made. And it aired on German TV before it was even in movie theatres in the US! The kids recorded it, because you guys had VCRs before we did — maybe that’s how your friends first saw it — it began to hit the streets, and the video recordings began to circulate around Europe. I remember hearing about kids doing the moves, the exact same moves the Rock Steady Crew do in the movie. That was when I realised it was spreading beyond my expectations.

This is so great. It almost raises the hair on my arm to hear you say this. Because I remember hearing about this movie and taking a train to Copenhagen to see it. I had my crew with me, and the cinema was packed with all the graffiti artists and breakdancers and electric boogie dancers and DJs and everybody. And it was completely white, completely and utterly white! The moment the film starts, everybody jumps up and stands in the cinema. It was unbelievable. And as the film goes on, everybody is dancing and standing on the chairs. And at that scene where Crazy Legs does his footwork at a party, halfway through the movie, we all start literally running around in the cinema – the cinema people are yelling at us – and we’re doing footwork and swipes and turtles up on the stage in front of the screen. It was like we were trying to jump into the movie.

And even though it sounds so funny today, I did walk around in my Michael Jackson lookalike suit – the knee pads, the big shoulders – and I did have my piece of cardboard to dance on. We would just put out our ghetto blaster in the pedestrian zone in downtown Copenhagen and do our moves. And if petty cash ran low, we had a hat.

Classic!

A few years later, after I stopped being so involved with dancing – I applied to art school. That was where I learned that historically many artists had worked on the street — performance artists, Marcel Marceau, the Situationists — and I suddenly realised what I had learned from being a street dancer. Later, as I became involved with art and space and architecture, I would think about how it felt to actually own a space — what it felt like to claim it and say ‘this space reflects my emotional agenda.’ I realise now that it was rooted in this idea of street culture and public space. And that is why I still have the Wild Style record today, and still listen to it.

You know, I didn’t know a lot about your work until the New York City Waterfalls, which I would notice at night driving home across the East River to my house in Harlem. I guess you claimed that space thoroughly and totally! Especially at night. There would be some lights on it, and it was just so exciting to drive past. I would almost crash trying to be sure I got a good look at it. It’s so great to hear that hip-hop, urban culture and street dance were sparks for that. Yours is one of the most unique stories I have heard about how this movement influenced someone. I could not have dreamt this up!

Of course hip-hop went on to become mainstream, and a huge business. You have successfully managed to balance the creative potential with commercialisation, which can work against it. But to go back to that early time: as I got a little older, MTV suddenly arrived. You started hosting your show Yo! MTV Raps, and suddenly people had access. Only then did it strike me, quite late in the process, actually, that improvisation is a major part of it as well. Improvisation is in every part of how we claim space, and improvisation is super important to my work today. How did that start off for you?

I come from a jazz background. My father was very close to the bebop scene and to the drummer Max Roach, and as a kid I heard him and his friends talking a lot about jazz culture. Thelonious Monk was my favourite musician. I found his number in my father’s phonebook one day and just called him up for a conversation. I was probably about nine or ten years old. His wife [Nelly Monk] talked to me for about twenty minutes! Jazz, she said to me, is like a conversation: you state your case at the beginning of the song, and then you give examples – you explain and support your argument. Each musician does that differently, and that’s improvisation. Once I got that, I was ready to apply it to other things. For me — and, I think, for African-Americans, for people who have very little — the actual core of improvisation is the idea that you have to find some way to make it happen. You don’t have as much as you need in any category — food, clothes, resources — so how can you improvise and make what you do have more you, more original, more flavourful? How do you make it different? That was the beneficial outcome.

And it’s like creating a dialogue. In jazz you allow the listener the fantasy of becoming a co-composer.

Or even a co-conspirator! Your description of hip-hop culture in Denmark reminds me of hearing Max Roach and his friends talking about how they felt more accepted in Europe, without the bullshit they experienced in America. That’s why so many jazz musicians become expatriates. Many were well-read and intellectual and felt better treated abroad than in America. Not that racism didn’t exist in Europe, but Europe acknowledged them as the creatives they were. When we found that first money to make Wild Style in Europe, the situation was a bit like what jazz artists had experienced.

I don’t think it’s just a lucky punch that Germany gave public money for the film. Having come out of the war, Germany really was looking for ways to support subcultures and respect identity, because it actually represents a set of values that comes with the public. These days, cuts are being made everywhere, but especially in America, to public support for grassroots and diversified cultural activity. And all the big museums in America are to a large extent white: the boards are mostly white; the funding is mostly white; the shows are mostly white; art history writing is still very white. There is still a long way to go toward equal presentation of other types of experience, whether Latino or Black or Latin American or whatever.

I’m so happy to hear you say it, Olafur. You know, discussions like this were the genesis of my friendship with Jean-Michel Basquiat. ‘How can we get in when we know there’s no improvisation going on at the galleries, on the boards, with the curators of these institutions?’ Jean-Michel and I would strategise on our assault on pop culture and we had what we called our Museum Club. We would often go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art together and just talk about paintings and have lunch and make sketches like we were art students. We had both spent a lot of time in museums as kids, so when we met we could discuss artists from Jasper Johns to Caravaggio. We were excited that we were both young and Black and could talk about all these painters, because we couldn’t talk about them with too many other people. Not many of our contemporaries knew these guys. We were going to find a way to get in to these institutions – working with music, working with film, working with art. And that is what Jean-Michel did and what I continue to do.

I am so glad we could chat, Fab. It’s just of great personal importance to me to be able to share this part of my life. To a large extent that period of my life — that prologue — has not figured very much in my art, and so I’m glad finally to have nailed it. And with the man himself. With Fab fucking Five … oh, man, I’m so excited!

Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life is on at the Tate Modern until 5 January 2020. Interview © Studio Olafur Eliasson 2019. First published 2019 by order of the Tate Trustees by Tate Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises. Courtesy tate.org.uk/publishing