“Imagine dividing your life up into the most significant memories and then adding photos, ephemera and commentary to it. Then imagine you’re 46 and have done a lot of stuff in your life… that’s where I am at the moment.” When we call Vinca Petersen, the photographer and multimedia artist is putting the finishing touches to her installation, part of the Saatchi Gallery’s Sweet Harmony: Rave Today exhibition (12 July – 14 September), a retrospective on rave culture and acid house. Unlike most of the show, which captures people on the dancefloor — in your face and off theirs — Vinca has gone down a different route with her contribution.

You see, Vinca wasn’t just a regular club kid — she lived it. She went from squatting in London during the second summer of love in 1989 as a 17-year-old, to joining a community of “techno travellers” who ventured across Europe, following free party sound systems and organising their own raves on route. Somewhere along the way, she became a successful model, and even interned at i-D as our then fashion editor Edward Enninful’s assistant, back in the early 1990s.

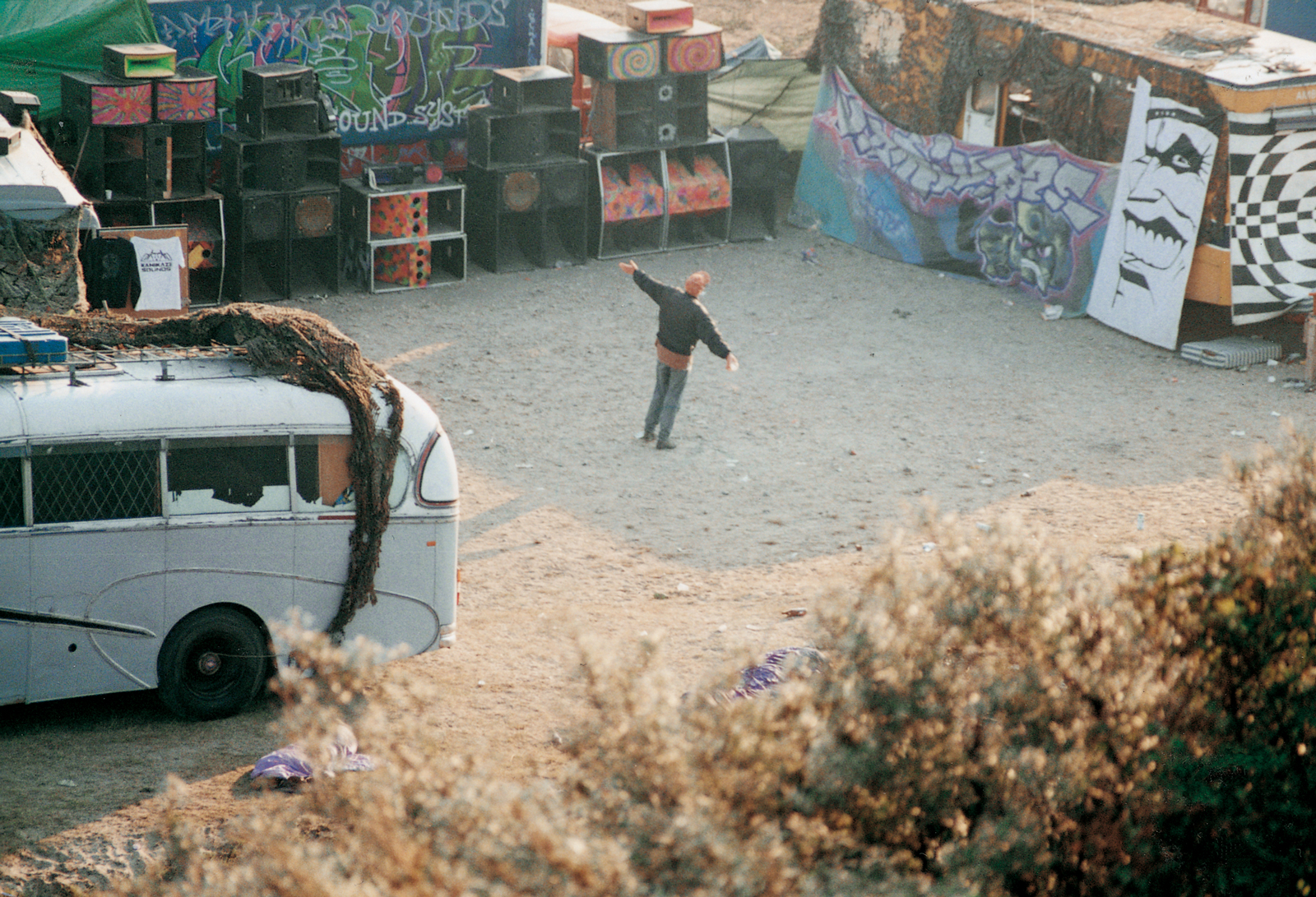

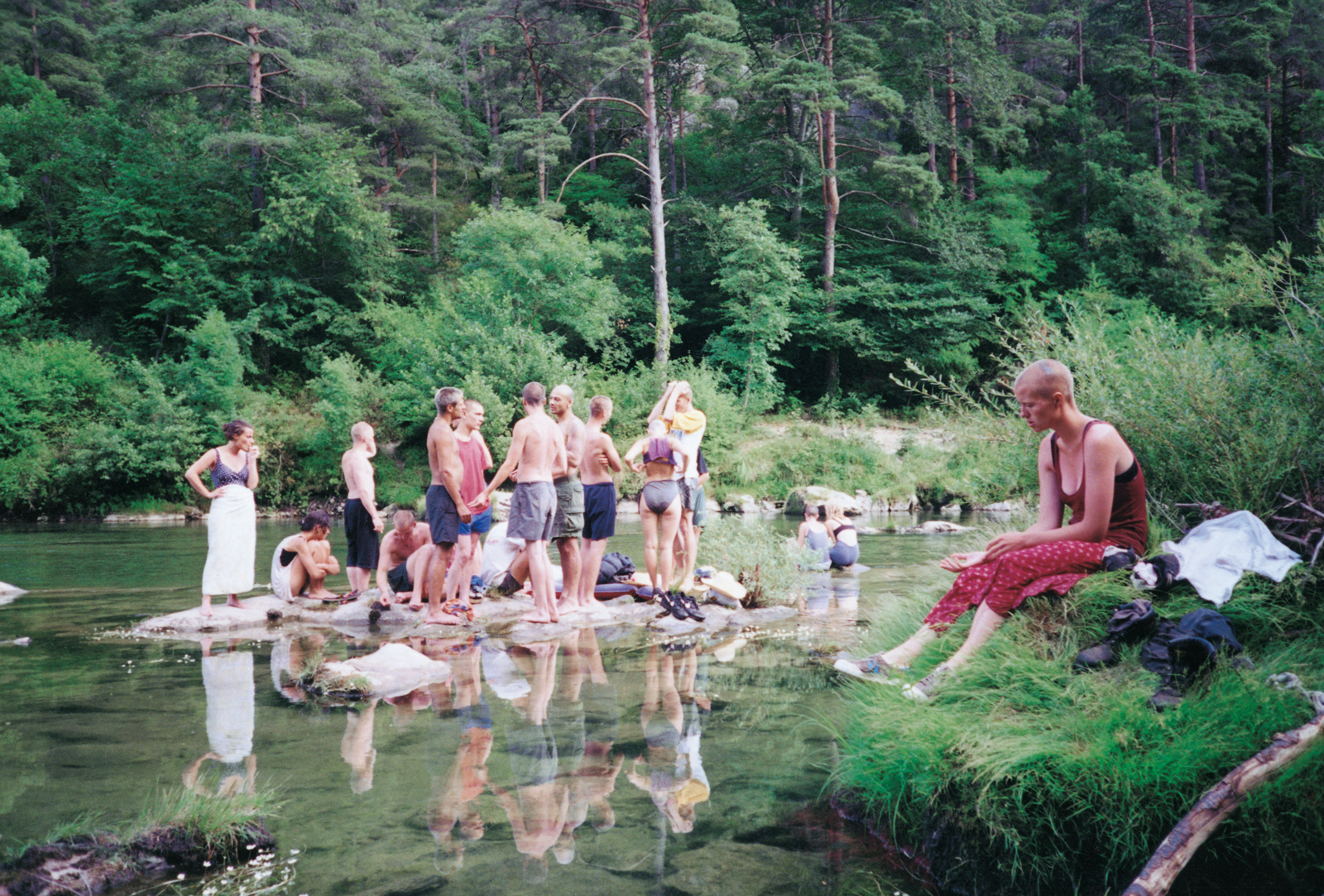

“I want the viewer to be taken on some kind of a journey, so I thought I’d go with some imagery that’s a little more abstract and dreamlike,” says Vinca of the photographs she selected for the exhibition, taken from her 1999 book, No System. In one image, a solitary figure with outstretched arms stands in a clearing, surrounded by RVs and an impressive DIY sound system, still going strong from the night before. In another, a woman is asleep in a lush green field, her head resting on a frisbee. These are the quieter moments that punctuate life on the rave road. “In my mind, No System was a kind of brochure for our way of living,” she says. “It was an invitation for people to come and join us.”

It was Vinca’s friend, the late, great British fashion photographer Corinne Day, who convinced her that her work would be of interest to the wider world, that it documented one of her generation’s underrepresented communities. But the fact that she’s been sharing it for the past 20 years, doesn’t make revisiting it any easier for Vinca. “I have been known to describe going into my archive as emotional and disturbing, slightly unnerving, not as comfortable as you might imagine,” she says.

“I think they kind of expected me to focus on photography,” she says of her installation, “but I turned this into something much more than that. My room at the Saatchi is all very interactive.” Alongside her photography Vinca is exhibiting a hand-drawn timeline of her life, dashcam footage from the front of her 7.5 tonne truck as it drives through the seemingly endless tunnels in Italy, and an invite to jump about on her well-travelled bouncy castle (more on that later). We asked Vinca to tell us more…

Which photograph from your selection has the strongest memory attached to it?

The River Conversation. It was taken in the Massif Central in 1995, the first summer that I left the UK. I hadn’t got my first live-in vehicle yet, so we were all in the back of my friend’s tiny Bedford Rascal van and I just knew that this was how I wanted to live. Not so much the raving or partying… but that river, a transient community, beautiful places, being free to talk and gather. That meant more to me than the actual parties. They were just a part of the week, but I loved the whole week. Having been a raver in London where you went out to your rave and came back home — even though I lived in squats and there was always company — it was that idea of being stuck in a house and a city. I just wanted to be outside.

Was there always music?

That’s an interesting question. There are different types of travellers, everything from Irish travellers to hippy travellers… I guess you could call us techno travellers, so music really was at our core. There was always music coming from somewhere, whether that’s a car stereo or a full sound system. It was different sorts of music too; reggae, drum and bass, punk. Of course there were quiet times too. I used to love the winter for the quiet. You’d do the big rave at the weekend and then there’d be much fewer people around and you’d spend a lot of time chopping wood, finding somewhere to park up, keeping warm and cosy. Still in small groups, but quieter.

Do you remember whether it felt important to document your lifestyle? Or were you purely taking snapshots of your world?

I very early on realised that after a night out, you’d forget a lot. The first few years of the more wild, semi-legal raves that were kicking off around London, I didn’t take so many photos. But when I started travelling with a community and living like that, I realised that I was witnessing so much and I really didn’t want to forget it. Then, in the mid to late 90s, I met a photographer [Corrine Day] who was very insistent that I take as many photos as I could. She gave me film and a camera and made me realise that this might be interesting to other people too; that I owe it to people to show them this way of life.

Was it all positive?

Most of the time life was good. A tiny percentage of the time, life was awful. I avoided putting that kind of stuff in No System though, because all the press I had ever seen on travellers and ravers was very negative and dwelling on the sickness of it. I thought I’d do something else.

You previously described “moving to the side to create a new kind of society”. Does the current state of the world make you want to do the same?

It was all about being counter-establishment when I was young. But what’s happened is that those kinds of statements are more mainstream now, and the dropping out has been appropriated into a kind of commercial package. There’s a huge lack of humour today, and humour is one of the most rebellious states you can be in. It’s quite uncontrollable. My darkest fear is that the humour has been drummed out of life. Young people are having to think about such serious issues very early on in their lives. So I think, if there’s something I’d like to bring with me and share through this exhibition, it’s the importance of having fun. Serious fun. Not syrupy commercial fun, but instead something that I call subversive joy. It’s something a little bit naughty. And we’re all born to do it.

Talking of which, tell me about this bouncy castle…

Laughter Aid! It’s a response to this emergency I feel happening, the need for more fun. I challenge anyone to step onto that bouncy castle and not smile or laugh or wet themselves. It was inspired by the bouncy castle that some travellers took over to India in 1998. They used to set it up at their raves. I wanted to do one last long journey before having a baby, just to try and get travelling out of my system, so my partner Zain and I decided we’d drive to Ghana in a car. I wanted to take something with me, to share with people. I wanted to enter communities and get involved, so I came up with this idea of a bouncy castle — an inexhaustible form of aid. We got a very old Toyota Landcruiser and took the bouncy castle all around Africa. It was great! Then when I formed the Future Youth Project, which is a charity I run, we took it to an orphanage in Ukraine, and then on to Romania for some street kids. It was a bit like a circus turning up, I guess.

And is the bouncy castle in the exhibition the original one?

It’s the same one! It’s covered in dirt. I haven’t even washed it, so it’s got the patina of many a laughing child and sweaty adult. And I guess the reason it’s here is because I suddenly realised that the emergency is here now. So it’s come back to heal over here.

Are people allowed to have a bounce?

That’s what I’m currently fighting for. As far as I’m concerned, they can get on it… they just might get in trouble with the gallery. But this is an open invitation from the artist.

What do you wish that you could tell your 21-year-old self?

Life gets easier. It gets more comfortable.

Sweet Harmony: Rave Today is at London’s Saatchi Gallery until 14 September. Vinca Petersen’s latest book, Future Fantasy is out now via Ditto and available here

Credits

Photography Vinca Petersen