It’s 2014. Dressed in Topshop and American Apparel, you’re flipping through Urban Outfitters’ vinyl section, carefully rearranging Arctic Monkeys’ AM and Lorde’s Pure Heroine beside your takeaway Starbucks for maximum Instagram appeal (an app on which you have 100 followers). You got the idea from Tumblr. You wonder idly whether your calling is to be a BuzzFeed writer or a photographer. Either way, you’ll definitely be living in a penthouse in Shoreditch or Brooklyn.

For years, the Zillennial existed in the public imagination almost exclusively within this frozen moment. Gen Z began romanticizing these supposedly halcyon days some time ago, captioning old Tumblr photos with a longing to have been a teenager when indie music ruled the charts, everyday style wasn’t so explicitly recycled from other generations, and Ryan Murphy was still making good television. Aside from that, Zillennials, the micro-generation born roughly between 1995 and 1999, have been more or less ignored, sandwiched between the juggernauts of Millennials and Gen Z, ricocheting between the two in search of a coherent generational identity.

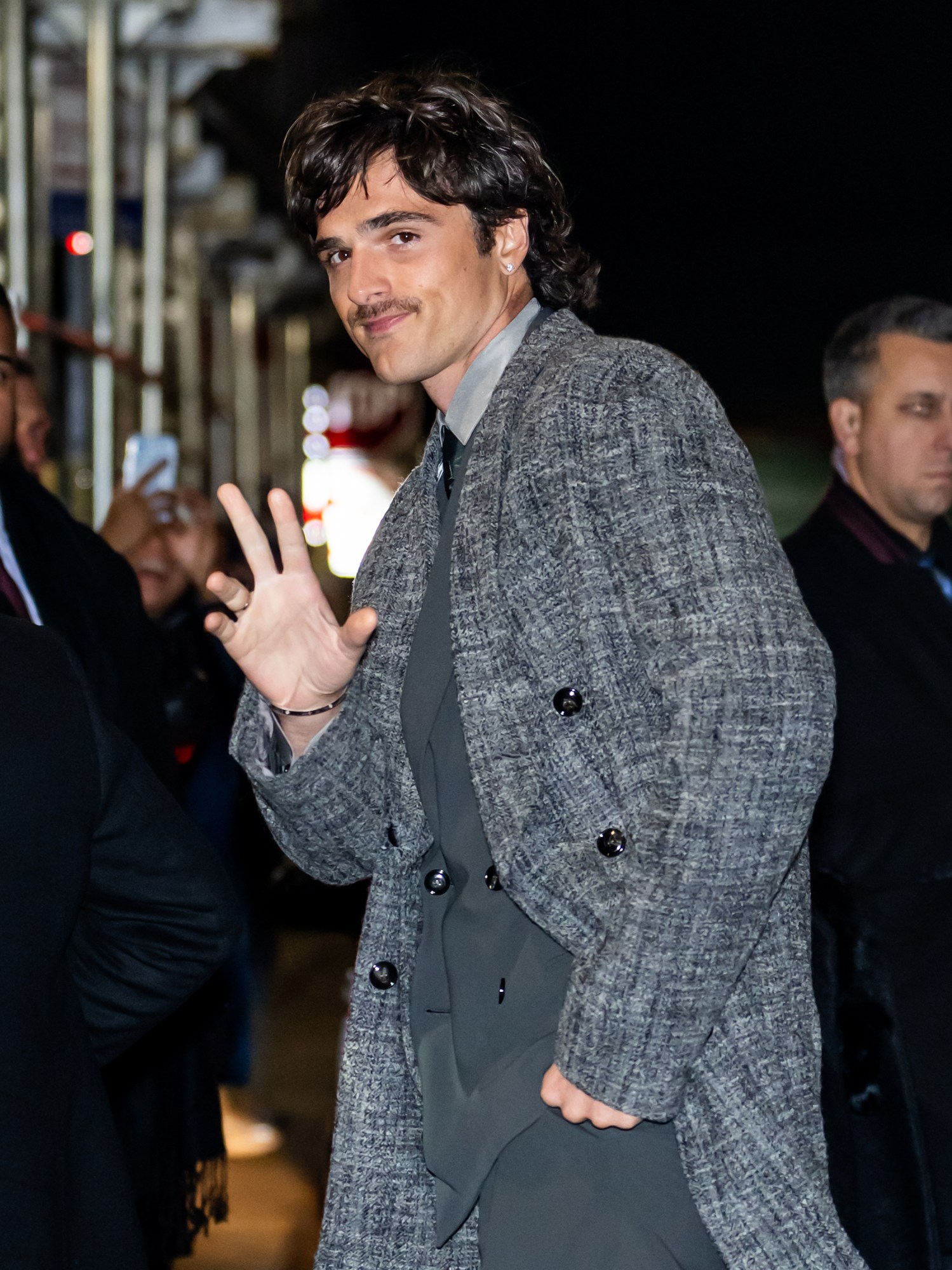

Now, though, Zillennials have grown up, and our cultural figures are becoming cultural leaders in their respective fields. That shift has been particularly visible this year. On a micro level, Jacob Elordi, born in 1997, went viral after telling Oscar Isaac that he used to reblog photos of him on Tumblr. On a larger scale, Lorde’s Virgin album has earned the long-awaited critical recognition that has followed her since adolescence, with reviewers noting her jaded portrayal of generational malaise. And in a testament to the duality of women, Kylie Jenner has resurrected King Kylie.

Then there’s Rachel Sennott, born in 1995, who first made her name writing funny tweets back when the app was blue and Rihanna was throwing digital hands at everyone. This autumn, she released I Love LA. “Sennott has captured the Zillennial condition in all of its dead-eyed, story-watching glory,” wrote Olivia Allen in British Vogue. “I am, of course, biased,” Allen tells me. “Everyone wants to be in on the joke, and as a 27-year-old who works in fashion and occasionally wears Tabis, I like to think of myself as the target audience for the Dilara Findikoglu references and Wildflower phone cases. I, too, have a graveyard of dead vapes by my bed and love overpriced, dimly lit dinners. Seeing this kind of incessant content-farming played out onscreen, arguably for the first time, affirms the camp absurdity woven into it all.”

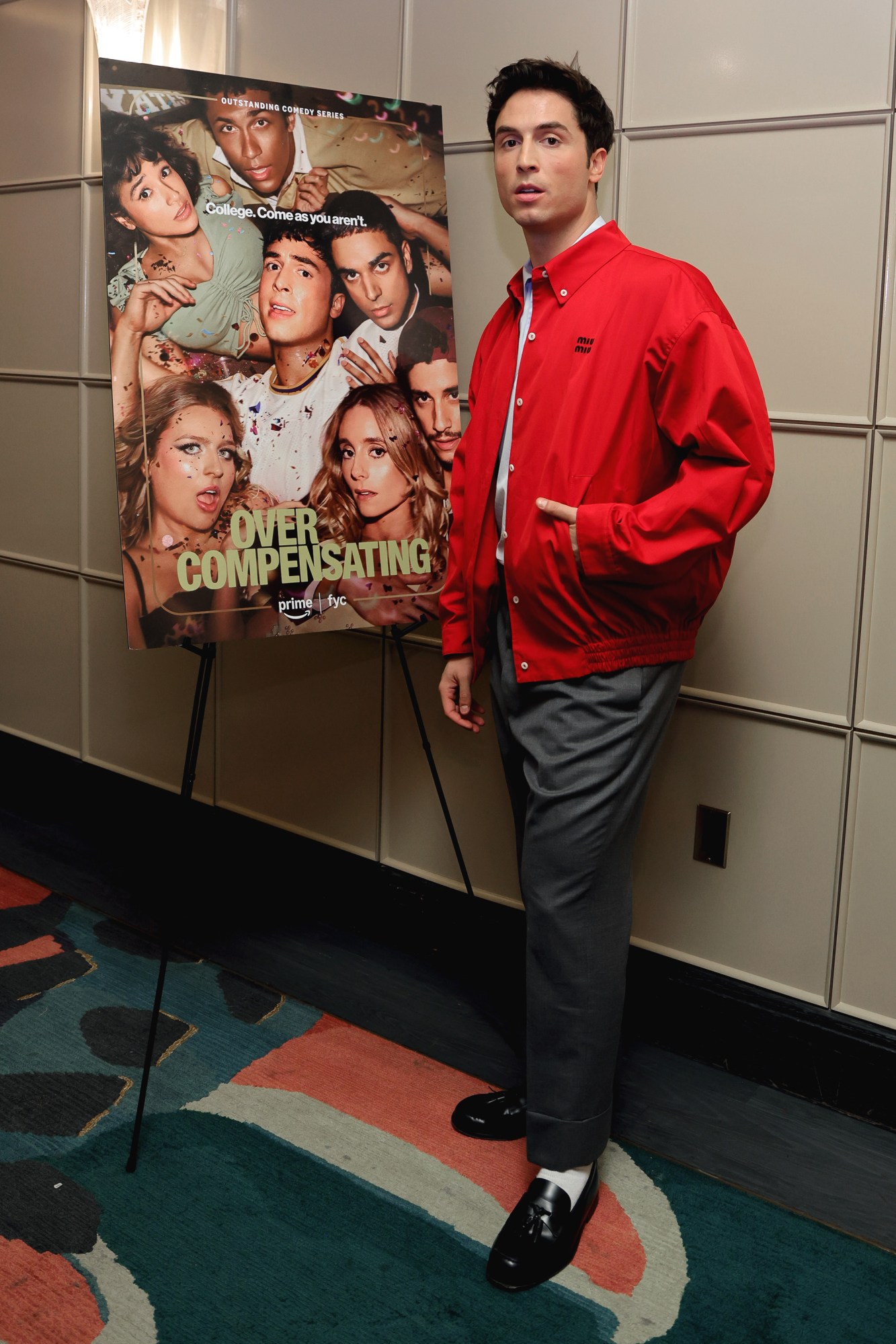

For a micro-generation that now finds itself in its late twenties, Zillennials finally have the cultural power to flesh out the nuances of our subculture on our own terms. There’s an argument to be made that the gothic sullenness that once defined the American Horror Story–sponsored era of chokers and creepers lives on in artists like Ethel Cain and The Last Dinner Party. On a more comedic note, it’s easy to watch fellow Zillennial Benito Skinner’s Overcompensating and recognize its exaggerated, sardonic tone as one shaped by a communal upbringing on Glee. With an Amanda Knox joke in the first episode and references to Glee throughout, this is culture made not for Gen Z’s understanding, but for those born just before it.

Even the Big Suits are starting to understand that there’s money to be made in telling the Zillennial story. And it isn’t limited to music and television. Publishing, too, is making space for what feels like an onslaught of Zillennial debut novels. Literary it-girl Anika Levy published Flat Earth this November to considerable buzz; Stephanie Wambugu, born in 1998, saw Lonely Crowds released to similar fanfare in July.

“It’s partly that many writers come of age in their late twenties,” says Ella Fox-Marten, assistant editor at Scribner. “But I also think Zillennials are uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between hyper-online readers and older readers who grew up without the internet. They’re translators, in a way. They can play both sides of the field.”

That fluidity of generational identity is certainly true for Wambugu. “Being on the cusp allows me to see that these descriptions are nothing more than coping mechanisms we use to express anxieties about being born too late or too early,” she tells me. “I wrote my novel from the perspective of a Gen X woman because I think the boundaries between generations are permeable.”

Perhaps it is this shapeshifting quality that places Zillennials, noughties kids, in a unique position for storytelling. Raised on Millennial earnestness, our teenage years were shaped by a transatlantic Obama-era optimism that once saw David Cameron appear in a One Direction music video. For many of us, our first foray into political activism was the 2012 Stop Kony campaign, a movement so peppy it was nearly impossible for tweens to resist. Its white saviorism soon became apparent; it’s hard not to think Gen Z would have clocked that immediately.

But it was 2012. Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe” played in fitting rooms, dominated radio, and soundtracked Justin Bieber dancing on a MacBook. Children of the Harry Potter and Twilight franchises, we developed an insatiable appetite for YA dystopia. Series like The Hunger Games and Divergent propelled young female leads to the forefront of fictional fights against fascism, arguably laying the groundwork for the political shift in youth culture to come.

Today, perhaps ever since that fateful year of 2016, the poppy, earnest, technicolor world that defined the Millennial era we were raised in is clearly over. Yet unlike Gen Z, we remember a time when the world didn’t feel quite so relentlessly bleak. In 2013, Lorde released Pure Heroine at just 17. While Gen Z may have retrospectively claimed “Ribs” as a TikTok anthem, it was “Royals” that initially thrust Lorde into the uncomfortable but deserved role of generational spokesperson.

“But everybody’s like / Cristal, Maybach, diamonds on your timepiece,” she sang, skewering the Gossip Girl-esque excesses of Millennial luxury. Still, the rejection was never puritanical. We were bored, but unapologetically hedonistic too, counting our dollars on the train to the party. More than a decade later, it’s no surprise that Lorde is once again leading the charge for a savvy, not entirely cynical micro-generation that is finally being given its due.