Photographer Yelena Yemchuk has come to define a retro, romantic aesthetic showcasing women as pillars of strength. Her latest body of work Mabel, Betty & Bette, is opening this weekend at Dallas Contemporary. Featuring 40 photos taken between 2012 to 2018, it pays tribute to women of the fashion industry, as it features models like Eva Herzigova, Carolyn Murphy, and Karen Elson.

Yemchuk is well-versed in the fashion world, having recently shot Lara Stone for the cover of InStyle, Grace Elizabeth for the cover of Vogue Russia, and has worked with models like Guinevere van Seenus, as well as actresses like Eva Green and Rachel McAdams, all shot with her trademark moody, vintage vibe that traces back to her upbringing in Kiev.

Though she has been a fashion photographer since the early 00s, she was overlooked during the Testino-Lindbergh era. Now that the female gaze is more prominent, she’s garnered a reputation for her surrealistic flair and counts Diane Arbus and Cindy Sherman as her influences.

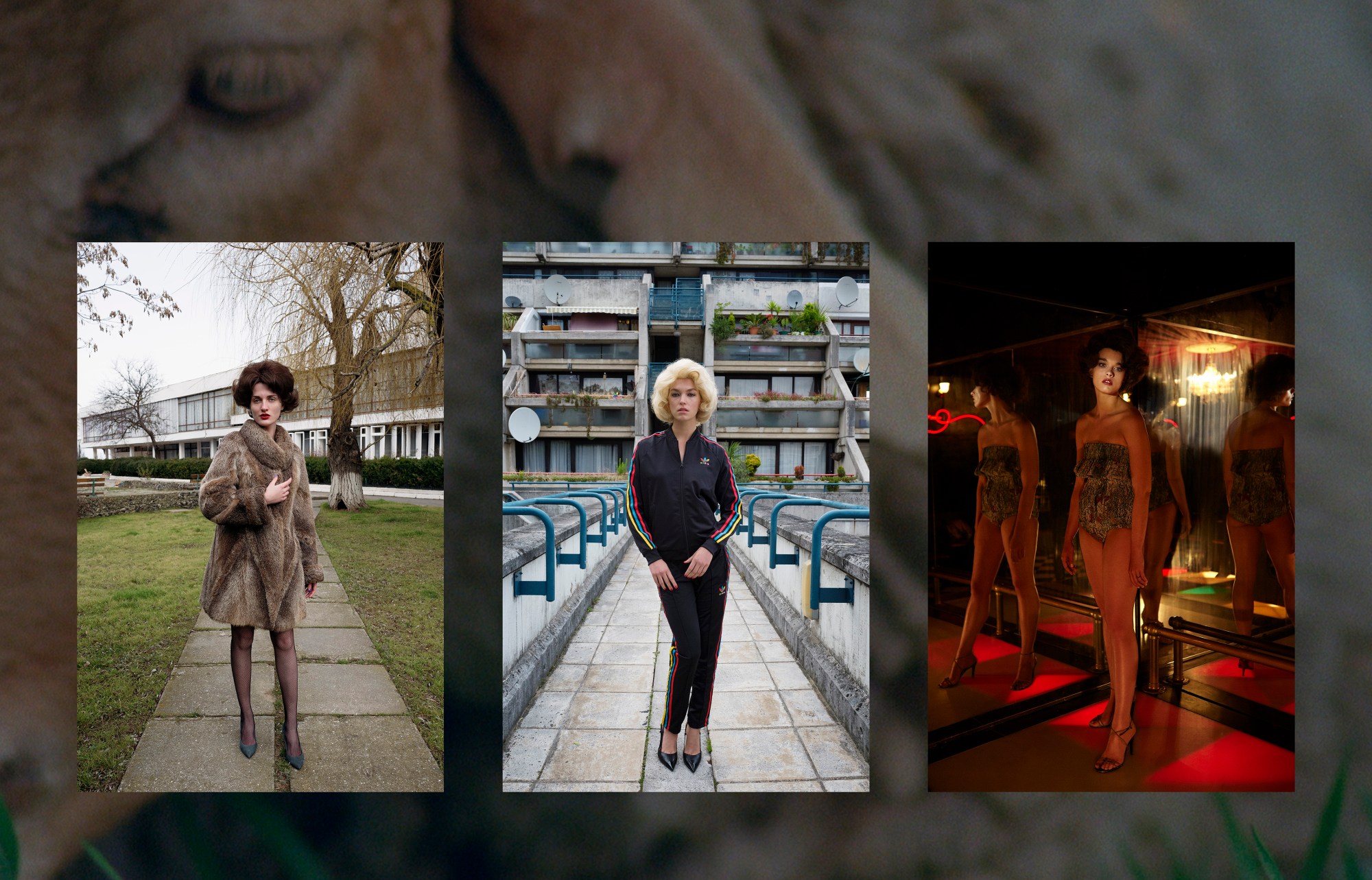

This new series, which travels next to the Ukrainian Museum in New York, showcases a dreamy vibe that ties into Yemchuk’s personal past. Just as she left Ukraine as a child, her work is riddled with an Eastern European vibe with models dolled up like 50s statues who are apparently lost, yet on a never-ending journey. This new series of captures them in retro wigs among the Ukrainian landscape—and is shown alongside a film featuring Ukrainian artist Anna Domashyna playing out three characters in elusive storylines written by Yemchuk.

The photographer, who has shot for i-D, is also releasing a new book about the Ukrainian city of Odessa this fall with Twin Palms, which she calls a love letter to the strange city. We spoke to her about Fassbinder, Man Ray, Brigitte Bardot and how this all began at a flea market.

Why is there a retro 50s film noir vibe to this series?

The first thing that triggered me was a photo I found at a flea market, these three women on a couch and they’ve been collaged. The heads on them were foreign movie stars, actresses, on top of these three nudes, women on the couch. I found it so fascinating, this play on character. I was thinking about me growing up in Ukraine in the 70s, as my family left in 1981, and we lived in such a closed, Soviet society, but I remember growing up seeing stars like Marcello Mastroianni and Brigitte Bardot, representations of idealized beauty. Something stuck with me, this vintage look. It wasn’t the first time I have referenced this period, but it wasn’t a conscious decision.

You’ve said before you’re interested in strong women, is that continued in this series?

They’re confused and lost in their expression and places; they’re going through this moment of loss. You’re not sure where and what you are. But I don’t think they’re victims of any kind. Being fragile doesn’t make you not strong. We must be aware of what strength is, vulnerability is strength, as well. To be conscious of all your emotions as a woman.

Why are these models featured for “Mabel, Betty & Bette,” is it based on real women?

In the photos, I wanted to use older models because it was appropriate for the project. It’s dealing with loss of self and identity. Models rarely depict who they really are in photos. They’re often becoming someone else, in this case, because when I wrote the stories of these three women in my mind, it was one person with three faces. Or one person existing in three different dimensions.

What dimensions?

I’m going to go into my weird existence now… I feel like our dream lives, for me, are so intense, and they’re so poignant, I would say. Who is to say that’s not reality, that it’s not a dream? Who is to say our dreams are not real? My 11-year-old daughter asked me that the other day and she said she hopes we’re not living in just one person’s dream because if that person wakes up, none of us are going to be here. I guess she gets it from me. I was always fascinated by directors like Rainer Werner Fassbinder and David Lynch, who deal with things that could be happening parallel to our existence, whether it’s déjà vu or coincidences. I go deep into this kind of atmosphere that connects who the person is, their environment, and why they’re there.

Was the accompanying film all shot in Ukraine?

Yes, it was. I met a model and I asked to photograph her for the project and sent her the reference photos. She wrote me back five seconds later and said: “I am the girl.” I said, “I know you’re the girl.” I photographed her in Ukraine then went location scouting and made the film with her. it was so much fun. She couldn’t travel to get out of Ukraine because it’s very hard to get visas. It made sense to shoot the film in Odessa, so it worked out. The film brings the photos together, the characters are all one person.

What was it like being a fashion photographer in the early 00s?

In 2001, I was working on a series of nudes and I met the designer Tabitha Simmons and we became friends. She asked me to shoot a story for Dazed, I shot on an 8×10 Polaroid. I had no real interest in being a fashion photographer, but I was into shooting women. I was at a point in my life where I needed to make more money. It was a good time to be free in photography.

It was a time when fashion photography was dominated by male photographers like Mario Testino, Bruce Weber, and Peter Lindbergh, now it’s friendlier with the female gaze. Do you see the difference?

It was a different time in so many ways. It was not only a male world, but not everyone wanted to be a photographer. When I told my dad that I wanted to be a photographer, he thought I was insane. It was a niche job—you had to be in the darkroom, it was a technical thing. People shot food, sports, and fashion. It then became a trendy rockstar thing in the late 00s, it became a new way of a generation to express themselves. It’s a great thing for women, it’s becoming less of a man’s thing.

Are women gaining more agency over how they’re represented? In a past interview, you said that sometimes women can be shown in a degrading light.

It depends on the woman; some women are taking degrading photos of other women. I’m not going to throw all men under the bus or make all women saints. It depends on how you see the world, women, and the person you’re photographing. I think the whole Victoria’s Secret thing; those are the people we should be looking up to as young women? I think that’s pretty gross, personally.

Are you still inspired by Dada and Surrealism?

Forever. Even my reportage photography, it has the strangeness and sense of humor of Dada and Surrealism because that was my first influence as an artist. When I directed the “33” music video for the Smashing Pumpkins, each image is shot as a 35mm photograph—we were the first open to do something like that. I like experimenting. I have made collages with animal heads on people, Man Ray has been a huge influence, Hanna Hoch as well.

What can we expect in your next photo book Odessa, will be released later this year by Twin Palms?

The book is coming out in October, it’s shot in Odessa over the past three years. A book of color photos — it’s my love letter to this strange and amazing city. It goes from portraiture to street photography, to still life, to landscape. It’s going to be a big book with a lot of pictures. I’m very close to my Ukrainian roots and a lot of my work has an eastern European vibe, I just can’t get away from it.