In 1994, with a New Yorker profile of a nineteen-year-old girl by the name Chloë Sevigny, Jay McInerney created his most enduring piece of fiction. The eighties Brat Pack iconoclast was tasked with following this rising anti-starlet—one who lived in squats, starred in Sonic Youth videos and attended smack wakes for a recently deceased River Phoenix—to decipher her allure and explain it to the common people. In this opus, McInerney sketched out the parameters for the fashion world’s now go-to descriptor for any young, bright thing gracing the scene: the It Girl.

Some twenty years on, reading McInerney’s piece is like observing a piece of fashion scripture. Every turn of phrase and observation of Sevigny has been recycled in contemporary media. It’s significant that McInerney was a novelist first and foremost, as in “Chloë’s Scene” Sevigny reads like a character rather than a real person. For McInerney—used to the elite party ecosystem and economic excess of eighties America—Sevigny, with her $10 outfits and underground raves, was a true enigma. Her style, in all its slender waifishness, represented the emergent decade; her alien nineties’s attitude was packaged and sold, simply, as “It”.

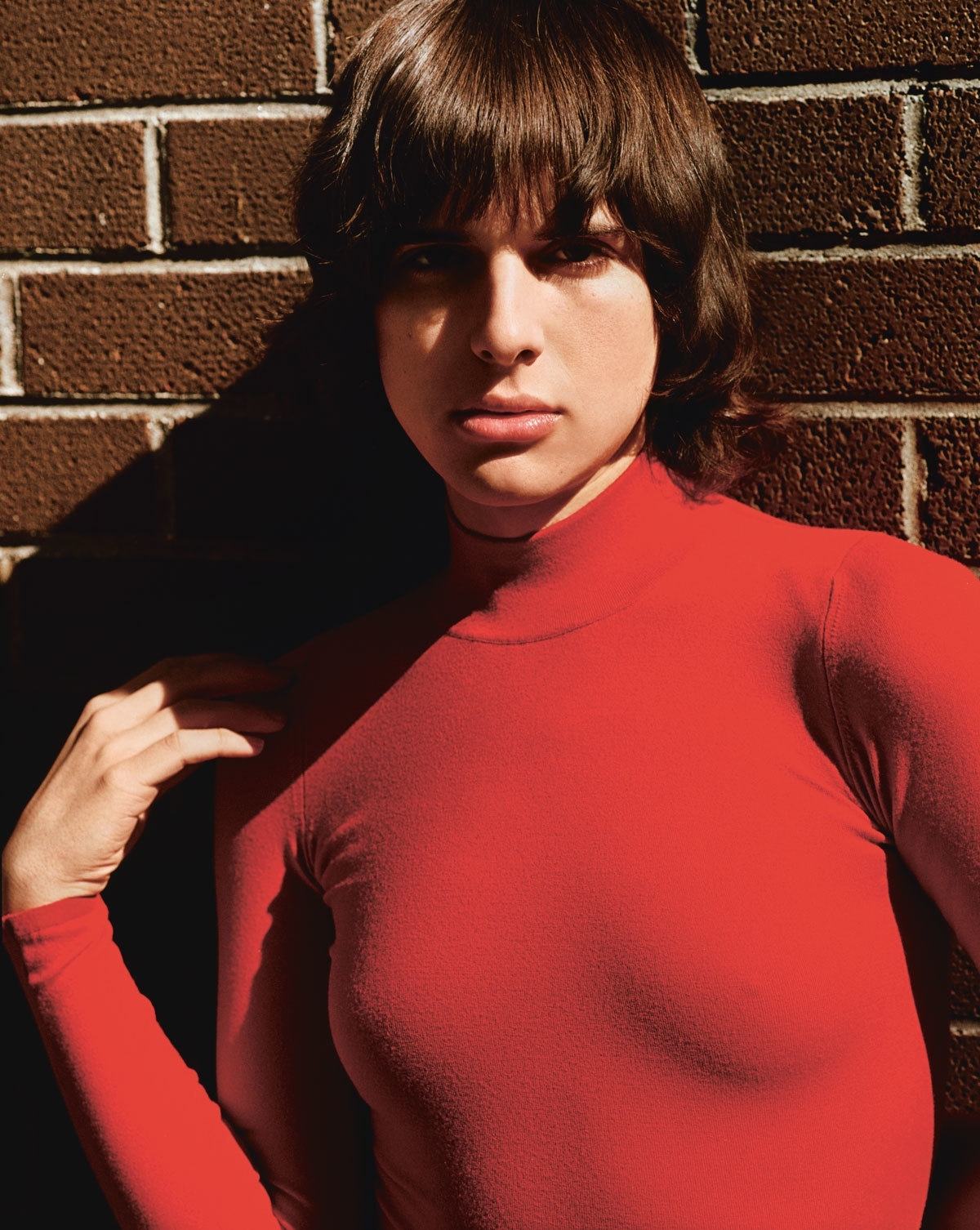

Covertly sexual, overtly stylish and unconventionally attractive—but most of all, the It Girl should be new

This is the primary qualification of the It Girl. Yes, she should be thin, white (or white-passing), covertly sexual, overtly stylish and unconventionally attractive—but most of all she should be new. Fashion looks to its It Girls to tell the future; they’re the shadow cast by next season’s trends and next month’s editorial spreads.

Obtaining this title is a lucrative business. In 2008, Alexa Chung became the latest in the lineage. She modelled her style on Jane Birkin and draped the hottest musician in Britain over her arm like the Mulberry bag that bore her name. She defined the decade’s affinity for all things Indie. So successful was Chung’s relevance that she forged a career based off her stylistic credibility and, in self-referential marketing genius, released a book titled It, cashing in on her acknowledged icon status. A few years later, Cara Delevingne stepped on the scene predicting the rise of the social media model and the cycle continued.

Both Chung and Delevingne’s trajectories show that, when successful, an It Girl should eventually graduate from her minute in the spotlight to build a career. But what happens when you can’t embody the ephemera? What happens when you’re not It anymore?

While some women have capitalised on the collective adoration they’ve received, others have been maligned by the hype. The commercial potential of lauding a woman as It means that the term is often too hastily applied. Cory Kennedy was a fleeting phenomenon, starring on the cover of NYLON, then little else. Similarly, Mischa Barton faded from view after her turn in The O.C. For these women, being tagged was the breakwater that scuppered their careers, just as they were beginning to crest. It’s easy to invest in the It Girl while she’s visible, but culture has begun to metabolise newness so quickly that if a woman isn’t omnipresent and ever-consumable—in every magazine, at every party, with all the right friends—they just aren’t considered It anymore.

The It Girl was ruined by her own PR value.

The term has been deployed so readily that the essence of the It Girl has been buried in HTML code. The It Girl was ruined by her own PR value. The blessing is in its vagueness; she’s nothing as specific as “actress”, “model” or “socialite”, but it carries enough credibility to shift magazines and garner clicks. Nowadays, It Girl is a phrase so commonly used cannot logically denote rareness; It should mean icon, but it really means fad.

All this editorial laziness has come at a cost; while seemingly any woman these days can be slapped with the label “It Girl”, its usage is far from representational. While we may point out that breakout actresses like Lupita Nyong’o and Hari Nef as proof of the label’s enduring power to mint an icon, these instances are so rare that they fail to prove the rule is still true—they are the exception. At its heart, the notion of an It Girl is designated rather than self-nominated; the media’s nominated It Girls often obscure the achievements of women of colour, LGBTQ women and women living with disability.

All this is not to say that our admiration for It Girls is misguided—female-to-female respect is crucial to ensure girls remain cultural tastemakers—but it’s time to reclaim stereotypes that were authored, innocently or not, by a man. The clue is in the name: how can we expect dynamism from someone we’re quite literally calling inanimate? “It” suggest a passive woman, an inscrutable stare, a mirror that reflects our own fascination, rather than the woman in question.

As the rise of social media allows blooming stars to control their own narratives, It Girl is starting to sound increasingly passé.

We rarely expect It Girls to do anything other than feed our thirst for trends and look good in party photos. As the rise of social media allows blooming stars to control their own narratives, It Girl is starting to sound increasingly passé. It would be remiss to describe of-the-moment women like Amandla Sternberg, Tavi Gevinson and Barbie Ferreira as “It” because they are so much more. Where Sevigny galvanised the image of the It Girl, these girls are deconstructing it; they don’t need profiles in the New Yorker to do the talking for them, because they’re doing it themselves.

The media has been caught in an attempt at recycling. Like Hollywood’s formula films and endless franchise prequels and sequels, fashion has clung to the silhouette carved by Sevigny so relentlessly that it’s become boring. It’s time that we followed the original It Girl’s lead by abandoning the sanitised remakes and setting the legacy straight. Sevigny’s allure came from her involvement with the avant-garde and the iconoclastic. There are plenty of rising stars now ready to walk in her footsteps—we just have to see them.

Credits

Text Rachel Wilson

Photography Marcelo Krasilcic, 1994