Taken from a lyric in Transome by Berlin-based musician Planningtorock, Kiss My Genders, an exhibition on this summer at the Hayward Gallery, flips the tired tendency for queer, trans, intersex and gender non-conforming bodies to be viewed as reducible subjects. Instead, the show reallocates to the artists the power to tell their stories. As its curator, Vincent Honoré, puts it, they become “creative actors of their own image-making and the masters of the circulation of these images.”

With 35 artists contributing over 100 works spanning 50 years, the exhibition is one of the most significant surveys of art dealing with gender identity and fluidity to date. Rather than be united under the banner of any particular ‘point’ or theme, works interact as if part of a multi-dimensional web chart, with each artist approaching gender and its associated identity politics on their own terms. Yet if a unifying thread is to be drawn, it’s an unflinching dedication to reflecting the complex shades of life beyond the periphery of normative existence, whether at its most humorous, at its most cruel or at the points at which these and many other aspects collide.

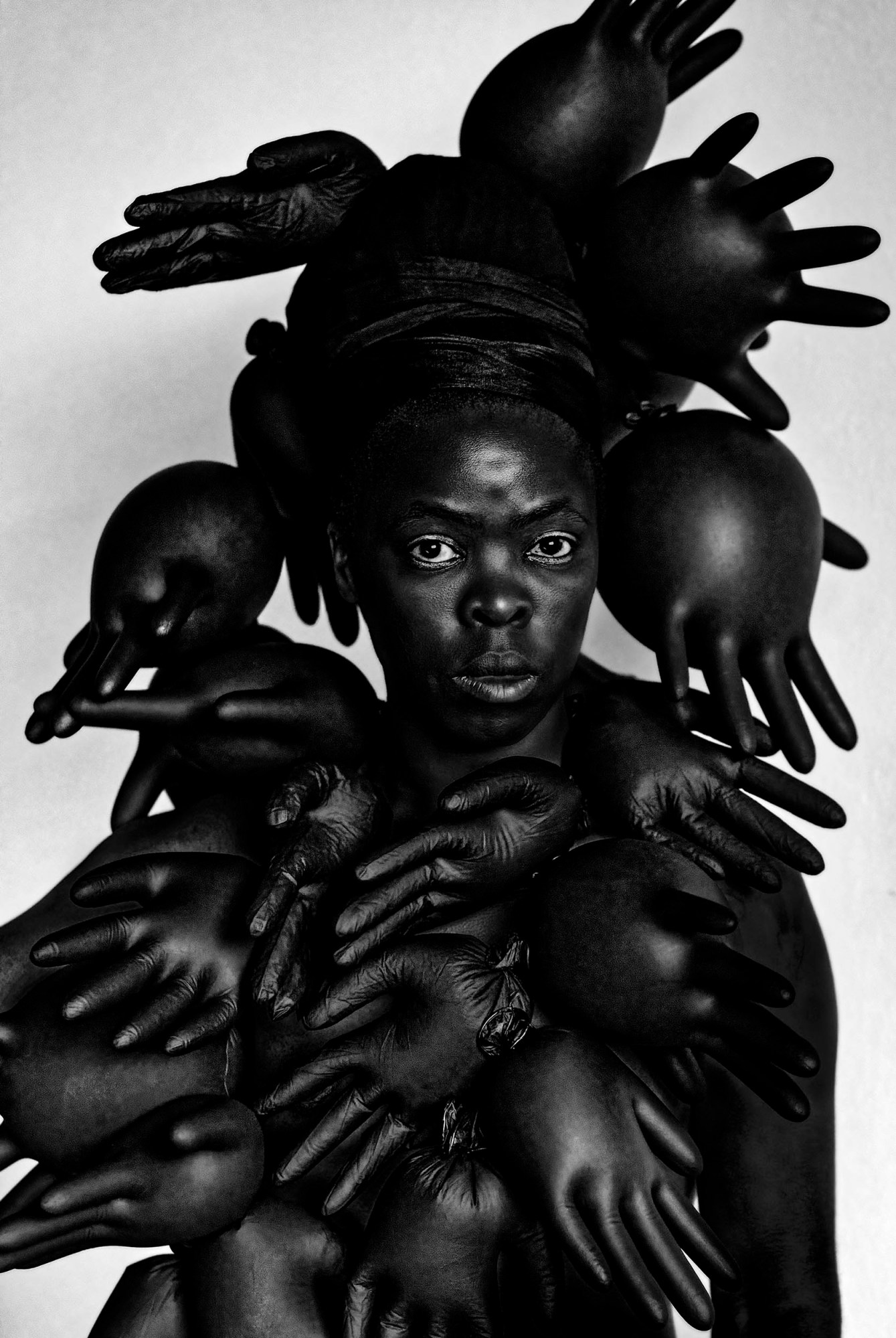

For Honoré, the point of departure in curating the show was the rather traditional medium of portrait photography. From the outset, he was intent on including Catherine Opie, whose images of figures from the San Francisco gay, lesbian and sadomasochistic scenes — of which she was part — are informed by the paintings of Hans Holbein. Her subjects pose with poise against brightly coloured backdrops, effectively using “a very traditional way of looking at portraiture to photograph a non-traditional and misrepresented community in a loving and dignified way.”

Honoré’s approach was also informed by the work of theorist Susan Stryker, who writes on the “historical legacy of transgender lives being viewed primarily through the depersonalising lenses of criminality or pathology,” he says. “Indeed queer people had been traditionally ‘documented’ by police or hospitals, as being others or outsiders. A traditional approach is a way to reclaim the dignity of (self-)representation.”

Across the exhibition, central to the reclaiming of representational agency is the idea of gender as performance. “Gender itself is a stage to be played with, to be manipulated, to become a tool for self-expression,” says Honoré. In some cases, this manifests quite explicitly, either in the content of the works or in the exhibition design. In others, it can be something as simple as the control implicit in a certain gaze or pose.

Among the most literal in its employment of performance is Jenkin van Zyl Looners (2019), a cinematic video installation. Mostly filmed in a complex of decaying film sets in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, the various locations serve as metaphors for purpose-built identities, squatted by Jenkin’s gang of genderless queens and undermined from the inside. “These sets have been continuously mutated to suit a succession of productions,” the artist explains, “and so fortresses, catapults and temples — all from awkwardly conflicting civilisations — jut out from beneath the desert.”

The scenes that play out among them have equal footings in violence, pleasure and lust, offering a queered take on the typical macho violence you might expect given the Hollywood-ready landscape.“ Looners sets out an idea of a kind of love-as-violence and violence-as-love. The film follows a trail of battlefields in which conflicts loop, day after day, without end. In the film, latex inflatables are built and burst by performers, anonymised by silicone masks, bearing weaponised genital accessories. Here, I was partially thinking through the contradictions inherent within masculinist queer spaces and their sites of simultaneous ecstasy and danger.” Running through the symbolic excess and campy horror, however, is a thread of wry humour, something that’s witnessed across much of the work in Kiss My Genders: “When humour is disruptive, it can be a funhouse mirror to project back tensions; it can expose the artificiality of normative identities,” states van Zyl. “Ultimately the film is a tribute to the gang of queens I perform and film with in the work, and my hope is that some of the weird joy and playfulness from its making could be infectious.”

In Glamrou (2016), i-D contributors Holly Falconer and Amrou Al-Khadi portray the undoing and reassembling of selfhood experienced by Amrou in their attempts to consolidate queerness and cultural heritage through drag. “When I first started drag at the age of 19, I experienced a profound fracture. While it liberated me to inhabit a self-constructed feminine alter ego, the process also entailed a sense of splitting. In renouncing my male identity, I simultaneously felt a divorce from my Muslim heritage, as if adopting a queer alter ego severed me from my conservative Middle Eastern upbringing,” Amrou writes in an essay published in the exhibition’s catalogue. “In the resulting photograph,” shot using triple exposure, “I attempt to wear a Middle Eastern rug as a dress; yet the mere attempt to create an intersection of my gender identity with my heritage results in a struggle that shatters the self into many different pieces.”

In the image, however, drag becomes a bridging force, a glue that binds the personal, the cultural and the political. “In Glamrou, the image’s disjointed nature speaks of the struggles Amrou Al-Kadhi has faced — but its ultimate unity is a testament to the joy drag has brought to their life,” adds Holly.

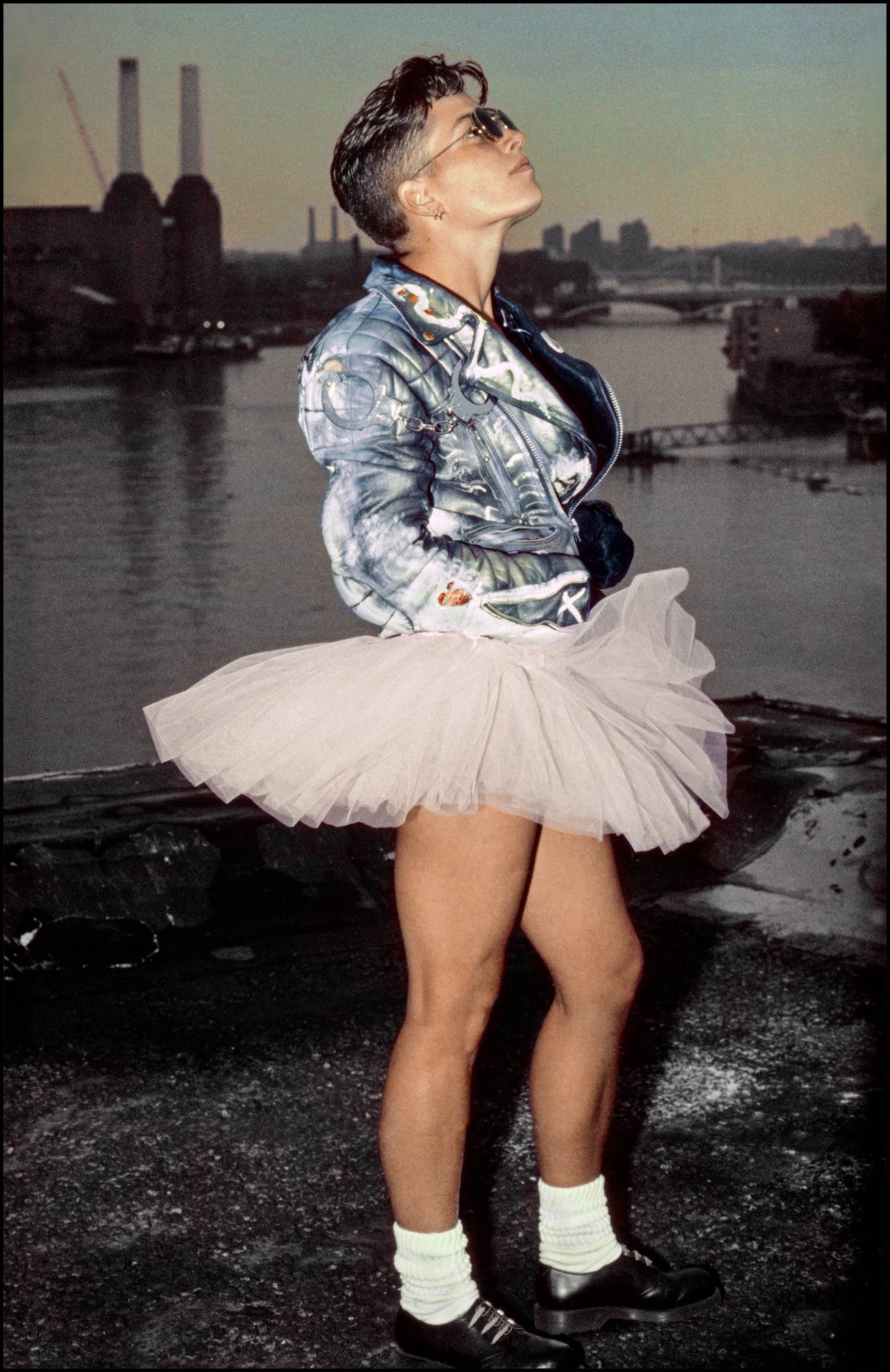

The work of Del LaGrace Volcano, a crucial fixture of London’s underground lesbian and drag-king scenes across the 80s and 90s, is similarly defiant. The exhibited works, which Del describes as being “more like encounter sessions from the 1970s than a traditional photo shoot,” depict subjects that both disrupt and proudly occupy their environments. In Robyn: Cold Store Romance, London (1988), a figure in a tutu with gel-slicked hair stands on a beach somewhere along the Thames, the chimneys of Battersea Power Station visible in the near-distance. “I am fond of the precarity of real-life and locations. My favourite stage is the big bad beautiful messy world,” says Del. Within these images, queer inhabitants are not fazed by attempts to be rationalised. Instead, both Del and their collaborators are “heroic and fierce figures” fully aware of their superpowers.

“I have had the great good fortune to have inhabited a wide range of bodies, genders and identities in my 60-odd years… I can make a case for having inhabited every letter of the LGBTQIA+ coalition of forces,” Del continues. “But when I discovered queerness, (which, remember, is all about challenging and questioning norms), something clicked. Then exploded into a zillion fragments as ‘queer’ was appropriated by fashion, the media and corporate powers. Tenacious as I am, I refuse to give up the only term that has ever been useful, as both a political and bodily being. I consider my work as an antidote to the tendency that many cultural producers have that depict queer people as either ‘fabulous but frivolous’ or sad, bad and dangerous to know. I consider my work a challenge to all systems of regulation — not just gender regulation, but the whole damn thing.”

Kiss My Genders, until 8 September 2019 at the Hayward Gallery.