As the collective Assemble pick up the Turner Prize for their work fusing art, architecture and social change, a new show opens up at the ICA that celebrates collectives from ’60s and ’70s Italy whose work also fused art, architecture and social change. But whilst Assemble recently transformed a local community and its environment in Granby, Liverpool, groups like Gruppo 9999, Superstudio and UFO were transforming the nightclubs of Florence, Milan and Turin half a decade ago. Radical Disco: Architecture and Nightlife in Italy, 1965-1975, which opens today, shows the work of the little-known Radical Design movement whose architects “sought to use their profession as a tool for societal change and to challenge the idea of architects’ role in society.” In the disco, they saw a space for creative freedom, intricate lighting, multidisciplinary experimentation and political action. We caught up with one of the show’s curators, Sumitra Upham, to find out more.

What was the movement’s reach? There were spaces in Milan, Turin, Florence and on the Tuscan Coast. Why didn’t it spread to the south of Italy, or outside Italy?

Between the 1950 and 1970s, Italy experienced an economic boom. State funding prioritised industrial growth. Mass factory production surged, exports boomed, new technology was adopted and Italian design became a global selling-point. Many working people relocated to northern cities like Turin, Florence and Milan. The south however was barely touched by industrialisation. Italy’s modern design industry became centralised in the north and as a result designers and architects migrated there. It was no coincidence that this was where the discos were built. Also many of the radicals met through The Department Architecture at Florence University. Interestingly, Piper club in Rome (the first of disco of this kind) spawned a degree course led by the Italian architect and painter Leonardo Savioli at the University on the topic of the “Piper” – the participants included Giorgio Ceretti, Pietro Derossi and Riccardo Rosso who then went on to design both Piper in Turin in 1966 and L’Altro Mondo in Rimini in 1967.

Why do you think it only lasted for such a finite period?

I guess in the mid to late 1970s the country saw a new political climate: proletarian revolts and new forms of urban conflict. Perhaps the utopian mindset of the ’60s felt distanced from this new world. Radical design came to a standstill in about 1975 with the advent of postmodernism. Music-wise, there was a demand for a new type of space to accommodate the burgeoning sounds of Italo-disco emerging in the mid to late 1970s. Discos were beginning to pop up across the country (not just in the north), as clubbing became more commercially viable and profitable for the leisure and tourist industry. This meant that the architects and owners of these discos were faced with questioning the validity and sustainability of their spaces.

Do you think the ten-year lifespan is also because that’s about how long most people’s vigorous passion if for nightlife lasts?

I think discos have a life span. The way people enjoy and consume nightlife is ever-evolving and if the clubs aren’t able to adapt or reinvent themselves to respond to future trends in leisure and lifestyle then they are bound to collapse. However, it seems that this was of little interest to most of these architects who were more concerned with responding to the present moment. I imagine many wouldn’t have been interested in transforming the vision of their clubs purely to succumb to these social and commercial changes. But some did, and are still running today, including Space Electronic and Piper Rome. The former is still run by Caldini, one of the original architects from Gruppo 9999 and the latter is one of Rome’s most well-known commercial clubs. Bamba Issa is now a 5* luxury resort known as Hotel Augustus.

Presumably drugs were a big part of the scene. Do you know what drugs were popular at the time and whether drug trips inspired much of the work?

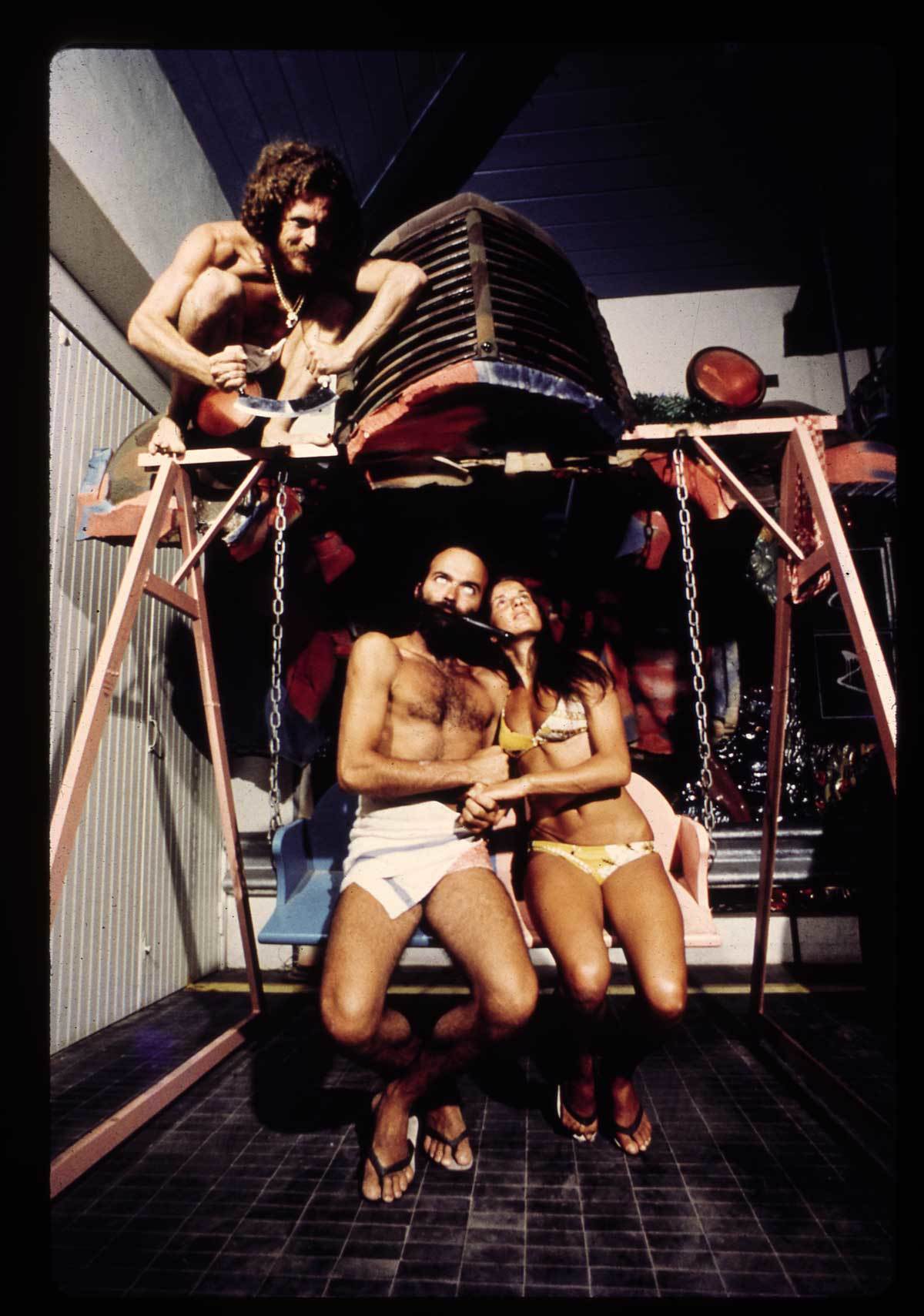

I don’t know of any specific connections to drugs, but of course it was the ’60s. They were certainly interested in exploring hallucinatory, fantastical and euphoric themes in their work. Particularly in Bamba Issa, which took its inspiration from the 1951 Mickey Mouse comic, Donald Duck and the Magic Hourglass. In this issue Donald Duck and his nephews search for a desert Oasis of Bamba Issa to collect sand for a magical hourglass that will bring them wealth! The beach-house turned club designed by Gruppo UFO, was transformed into an oasis with camel sofas, large lanterns and hourglass shaped furniture to reference the comic.

What was the main music at the time, or did it depend on the club?

The main music genre was progressive rock. It was the swinging 60s when many of these spaces opened. Bands like The Beatles, Rolling Stones and Velvet Underground, as well as Bob Dylan and Brian Eno, were blowing up and changing the public’s perception of what music could be. Many of the architects visited the UK and US to experience this music live. Some would approach acts to play at their spaces back in Italy. Piper in Rome for example programmed many legendary performances from the likes of The Who, Pink Floyd, Genesis and The Byrd. The more experimental spaces, like Gruppo 9999’s Space Electronic, would feature live performances from British acts and Italian prog rock groups including Audience, I Dik Dik, New Trolls andVan der Graaf Generator and the likes of Dario Fo, Franca Rame as well as New York group Living Theatre.

Do you think they felt like they were going to change the world through their work? There seems to be a sort of “evangelism” to these kinds of movements.

Perhaps. The utopian energy and experimental spirit of the ’60s and ’70s was a major factor in this. The rise in countercultural activity led people to believe that social change was possible. They were interested in changing architecture certainly, and re-establishing its role in society. To them, modern design had reached a stale state and was becoming increasingly detached from real life and real people. They saw discos as the ultimate social setting, and in them there was potential to connect with the world through architecture on a far more personable level than ever before. The dance floor came to represent a fluid space for multidisciplinary experiments. The movement was deliberately subversive: it was exaggerated, playful and experimental in form and function. It was often politically-charged, critically-engaging with mass consumerism, urban infrastructure, ecology, technology and the dominance of American culture.

What kind of impact do you think the movement had on wider architecture?

It’s difficult to say, as it’s a forgotten history that many designers will not have even been aware of, despite the fact these discos are some of the only examples of radical design ever being built! To my knowledge, there has never been a movement quite like it. Disrupting the notion of traditional architectural duration through experiments with performance and new technology seems to me quite radical even today, and yet it was being explored back in the ’60s by these architects. I think architecture could learn a lot from this movement.

Radical Disco: Architecture and Nightlife in Italy, 1965-1975 opens today until 10th January 2015.

Credits

Interior of L’Altro Mondo, designed by Pietro Derossi, Giorgio Ceretti and Riccardo Rosso, Rimini, 1967. © Pietro Derossi.

UFO, lovers on a swing chair, Bamba Issa, Forte dei Marmi, 1970. Photograph by Carlo Bachi, © Lapo Binazzi, UFO Archive.

Live music inside L’Altro Mondo, Rimini, 1967. © Pietro Derossi.

Space Electronic during the Mondial Festival, co-organised by Gruppo 9999 and Superstudio, Space Electronic, Florence, 1971. © Gruppo 9999, courtesy of Carlo Caldini.

4 UFO, camels in the caravanserai inside Bamba Issa, Forte dei Marmi, 1969. Photograph by Carlo Bachi, © Lapo Binazzi, UFO Archive.