“I was going to begin my tales of this city with a statement about how long I’ve been here, but the phone rang,” the Italian-American photographer Patrick D. Pagnano (1947-2018) wrote in a notebook on April 16, 1974 — just six weeks after he and his new wife, Kari, arrived in New York City for their honeymoon.

After spending their first week at the Times Square Motor Lodge, Pat and Kari found a cosy apartment on Thompson Street in the heart of Greenwich Village, which was then home to the bustling Italian-American community. “He loved the neighbourhood,” Kari says. “The Italian ladies in our building brought chairs down to sit on the stoop. There were a number of mafia-related characters that we always talked about. There was a guy on the next block, Sullivan Street, always walking up and down the sidewalk in his bathrobe.”

Pat was in his element. “The building we live in is practically all Italians,” he wrote in his notebook. “On Sunday you can smell the garlic and tomato floating from floor 1 to 6.” Undoubtedly the scent of Italian food evoked memories of home. A second-generation Italian-American, Pat was raised in a multi-generational home in Chicago’s South Side during the 1950s and 60s.

His family faced the horrors of ‘urban renewal’ twice in Pat’s youth: first when the government seized his father’s store to build the notorious Cabrini-Green housing projects where the movie Candyman was based, and then a second time when the family home was razed to build the University of Illinois in Chicago. These experiences shaped Pat’s outlook, building a firm sense of solidarity with the working class.

After discovering photography while studying at Columbia College Chicago in the early 1970s, Pat realised he’d found the perfect way to engage with the world and express himself. After visiting New York, Pat fell in love with the city’s chaotic, freewheeling energy and decided it was time to pursue his dream of becoming a professional photojournalist, but, like many new arrivals, Pat struggled to get his start. “This is a really large city. I stopped and looked around at all the large buildings, traffic, and people — most of which were of Latin descent. At that moment I felt my insignificance and a little fear to top it off,” Pat wrote of a jaunt along 14th Street.

“I still feel very insignificant. Almost everyday I’m out showing people my work with no real positive results. Most people act rather positively, some rather passively — you know, like they’re doing you a favor…. All I can do is wish for a little help, the bills are beginning to trickle in and I feel pretty bad about putting the whole load on Kari. She is a really fine woman and much more than I ever deserve. I hope she continues to stick by me.”

Indeed, she did just that — becoming what Kari describes as “his harshest critic and his biggest supporter” for 44 years. Although Pat’s first months in New York were a struggle, he soon found work as a freelance photojournalist during the sunset years of print’s golden age.

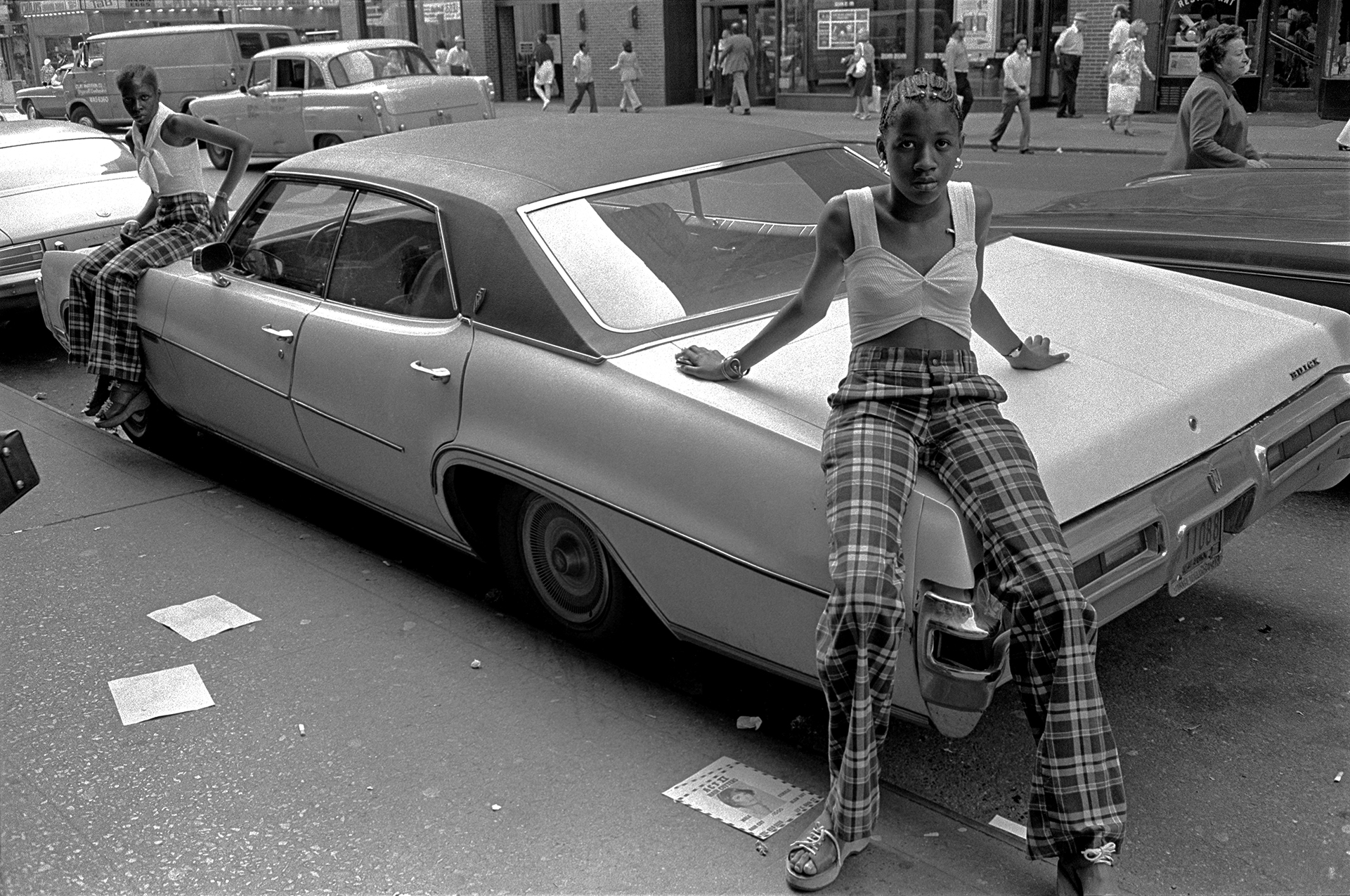

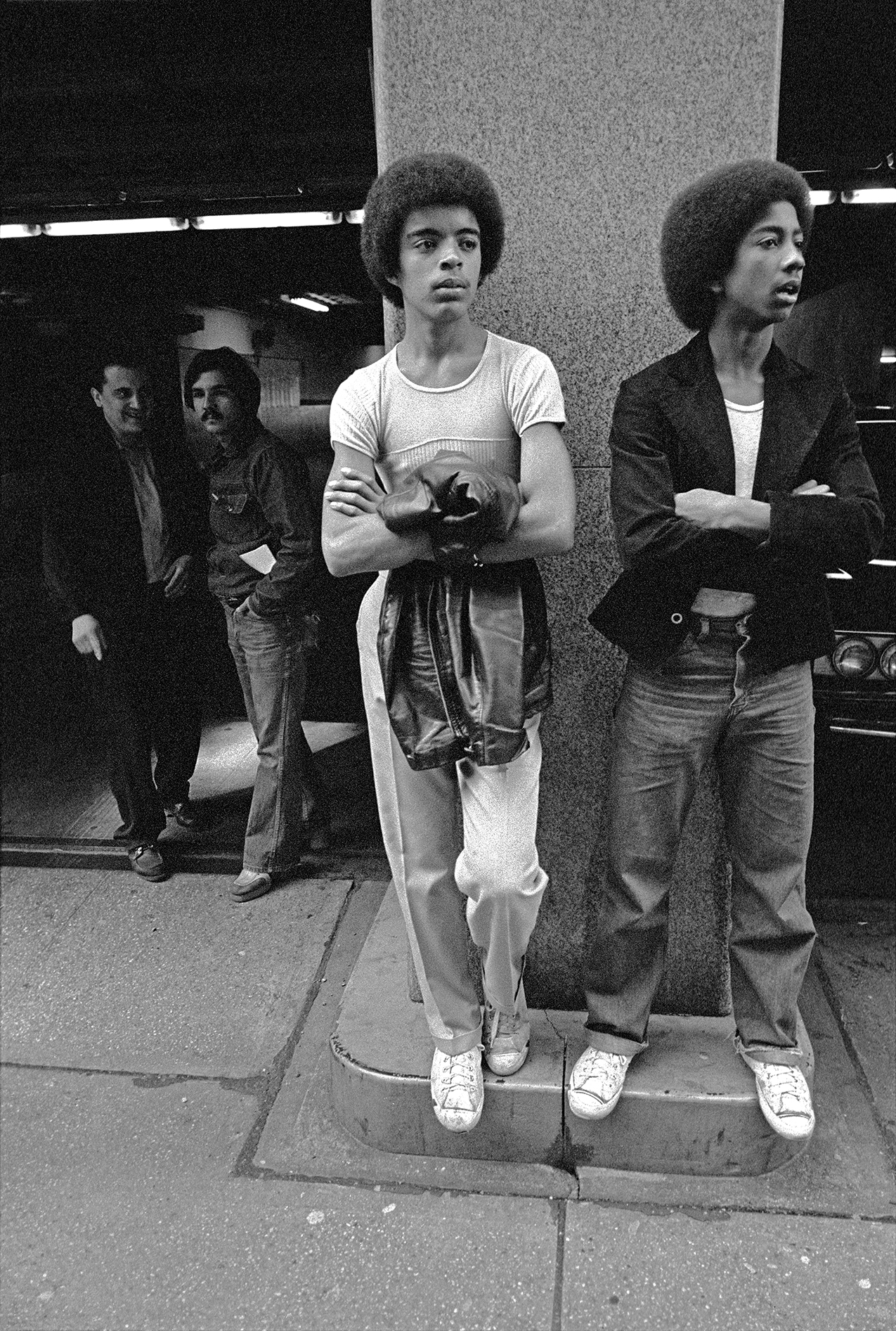

Like many working photographers, Pat always made time for his own art — street photography, the joyful refuge of the flâneur, who takes pleasure in being among the people and observing with his camera. Amid the intense, frenetic frequencies of the street, Pat spotted tender moments of poetry and bliss, sublime scenes of daily life that only he stopped to appreciate. Like his idol, Henri Cartier-Bresson, who observed, “Every image, each moment of dance, presents an emotional connection between people,” Pat made photographs with effortless grace.

“On the weekends, we might take a walk from our apartment up to Central Park, and Pat just did it fluidly,” Kari says. “He cradled the camera in hand so that it became part of his hand. He rarely stopped. He would see someone that interested him and moved so quickly that they didn’t notice him. He was very smooth.”

In 2002, Pat published his first book, Shot on the Street, a culmination of work born from desire and need. “I’ve been trying to discover what and where my little slot is in photography,” he wrote. “It generally takes effort to get me going but once I’m out I feel great.”

One week later, Pat described the day’s events, writing, “I ended my sojourn with a trip to the Statue of Liberty. It was a peaceful boat ride; it almost seemed like a pilgrimage for freedom, up to the crown after my previous experiences. I’m beginning to like my solitude, it gives me a real understanding of the world around me.”

A book of Patrick D. Pagnano’s ‘Empire Roller Disco’ photographs will be published by Anthology in 2022.

Credits

All images © Patrick D. Pagnano