“POV: It’s 2016 and you just spent your last $200 at Sephora just to go home and use it all with nowhere to go,” reads a TikTok from @mannymua733. If you’ve been in the online beauty world long enough, this image needs no explanation. That’s not just any TikTokker, that’s Manny Guttierez, aka Manny MUA, once a reigning beauty YouTuber. And that’s not just any eyeshadow palette he’s holding, it’s Anastasia Beverly Hills’ Modern Renaissance, a must-have for any beauty collector in the mid-2010s. And you don’t need to be told that the world the video references, back when we watched YouTube to learn how to cut a crease for no reason other than the pure love of makeup, no longer exists outside the simulacrum of a TikTok filter.

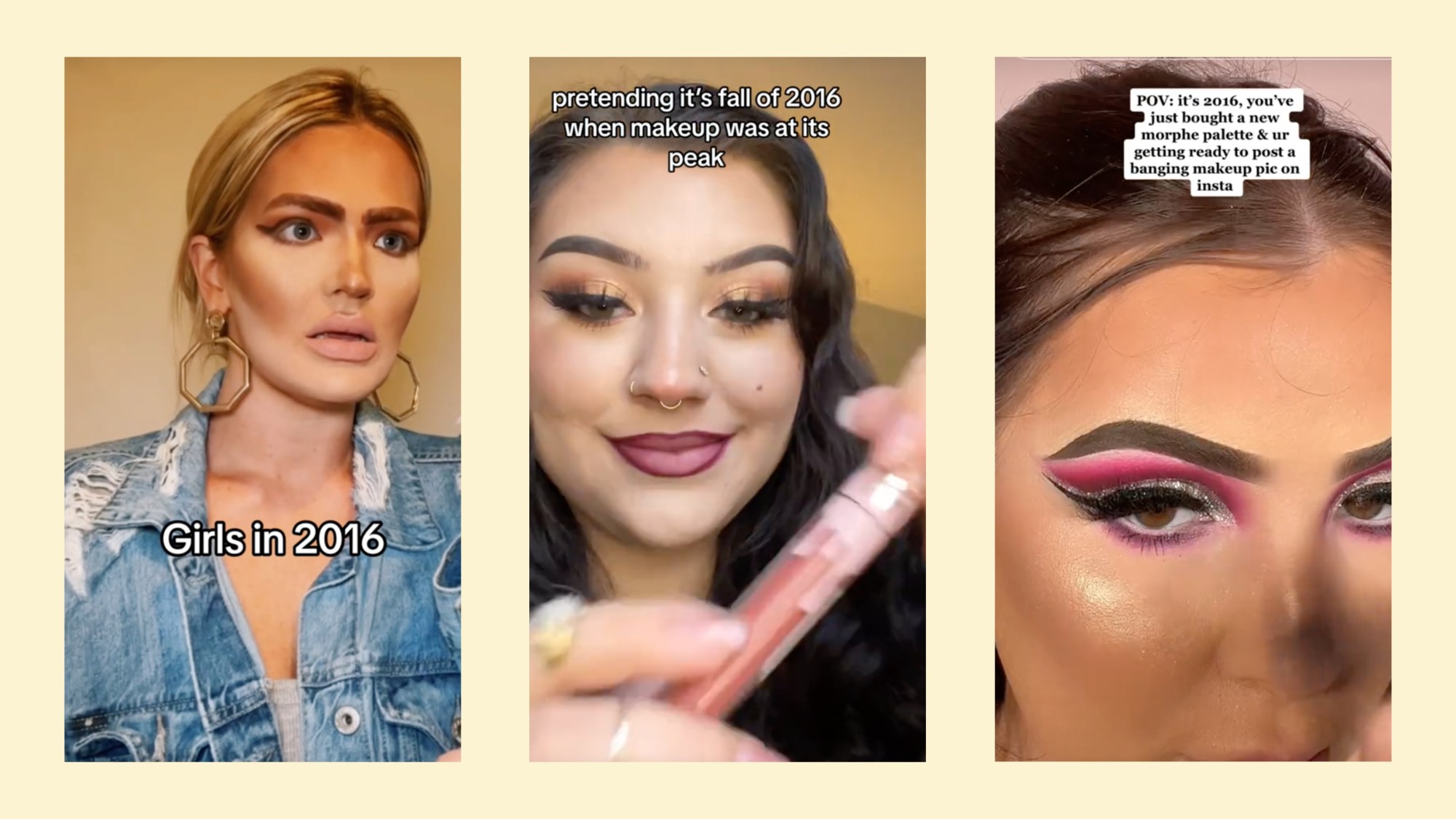

To be clear, plenty of people still run makeup YouTube channels, some of them painting their faces with the same unabashed glam as always. But as that video shows, YouTube-style beauty’s peak of influence is far enough in the rearview mirror for it to be primed for a reexamination. Today, it is being filtered through the lens of nostalgia, reemerging in the form of parody and throwback TikToks, all under the label “2016 makeup.”

Seeing nostalgia for “2016” might cause some to say, already? Seven years isn’t usually long enough for a bygone trend to feel worth pining over (fashion hasn’t even revisited 2008’s 3⁄4 length leggings under dresses — remember those? Now you do). And if we’re being pedantic, many of those makeup styles didn’t actually originate in 2016 — techniques like baking were popularised by drag queens long before and Jackie Aina, a pioneering influencer of the era, has been roasting what we call “2016 makeup” since 2014.

And yet “2016 makeup” is a potent label because 2016 feels lightyears away from 2023. “2016” is shorthand for a “before” era, not merely for beauty but the world as a whole. “And it was the last time I was happy,” says one commenter on the aforementioned Manny MUA video, with 12.1K likes no less.

2016 was before dramageddon, before the cynical cycle of celebrity skincare brands, before Bold Glamour filters. And also before President Trump, before COVID. The apex of King Kylie’s reign, a time of lip kit mania and copying her ombré brows. A time sandwiched between two recessions when maintaining your VIB Rouge status at Sephora seemed like a reasonable thing to aspire to. It’s hard not to feel nostalgia for such an era after living through years of constant “unprecedented times” and nationwide burnout. And there are few tools more powerful than style to transport ourselves to another time.

Like a good genre novel, the halcyon days of YouTube beauty operated on a series of comfortingly familiar video tropes —- hauls, reviews, empties, GRWMs (Get Ready With Me, for the uninitiated). The longer the video, the more drastic the before and after, the better. This was the era of erasing all of your features with a full-coverage matte foundation and then drawing them back on again, albeit in a slightly different part of your face. Each creator had their own style, but their appeal was largely the same: suddenly you no longer needed to be a professional makeup artist to learn to do a complex eye shadow look or contour your cheekbones.

YouTube beauty spoke to an increasingly online world, not just in its heavy, camera-ready makeup application, but in its populist bend: any regular person with an internet connection and an eye for eyeshadow could grow a following and make themselves a star.

SUBSCRIBE TO I-D NEWSFLASH. A WEEKLY NEWSLETTER DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX ON FRIDAYS.

By 2023, TikTok has only accelerated that possibility, with overnight fame in arms reach of just about anyone. But the longform aspect of YouTube meant beauty influencers needed real skill and knowledge to foster credibility. the speed at which TikTok operates has made such in-depth reviews impossible, with influencers like Meredith Duxbury more known for gimmicky techniques to stop you mid-scroll, or their glamorous (and often controversial) brand trips à la Alix Earle. As Vogue Business reported last year, influencers’ over-reliance on sponcon has eroded the credibility that drew viewers in to begin with, leaving consumers largely mistrustful of beauty creators. It’s no wonder that the world of 2016 beauty seems appealingly amateur by comparison.

Nostalgia for 2016’s hyper glam also coincides with growing fatigue for our contemporary minimal aesthetic. The rise of Glossier, multi-step skincare routines and a pandemic that forced many inside and behinds masks made the high-maintenance matte skin and carved out eyebrows popularised on YouTube appear passe by 2020. Beauty has since valorised “wellness” rather than glamour, with the glowing, dewy skin of the “clean girl” the reigning aesthetic post-2020.

But beauty consumers are growing weary of the promises of the clean girl look, which rather than lessening beauty standards has in fact heightened them. The dewy skin, flushed cheek look requires wearers to not only possess near perfect skin, but also only wear makeup that is nigh undetectable, keeping all the labor that goes into such a look behind the scenes. And though white celebrities like Hailey Bieber are often held up as the pinnacle of clean girl beauty, many have pointed out that its hallmarks like a slicked back bun and glossy lips are in fact borrowed from Black and Latina women.

That said, in revisiting 2016 beauty, consumers are also reflecting on the bad habits and rampant overconsumption the era fostered. “Raise your hand if you were personally victimised by the YouTube beauty guru era,” says Tiktokker @melworeit in a video decluttering her bloated, expired makeup collection. “Who else was obsessed with the 2014 beauty empties vids,” says creator Brittney Reynolds, who recently went viral for her $36,000 of credit card debt — a not insignificant amount of which stemmed from high-end beauty purchases.

And to the joy of brands that want consumers on a constant spending spree, the normalisation of beauty overconsumption has never gone away, no matter what look may be in style. “POV: When you got money to spend on #FentySnackz but not to fix that weird sound your car’s making…” reads a caption from a recent Fenty Beauty Instagram post.

But still, why call it “2016 beauty” rather than 2015 beauty; the year Jaclyn Hill and Becca released the seminal Champagne Pop highlighter? Or 2017 beauty, the year before dramageddon made beauty influencers’ nasty underbelly public. Or simply YouTube beauty, for that matter? Well, 2016 represents a jolt back in time like no other; there’s a reason it was dubbed at the time the Worst Year Ever. Little did we know…

“Even before November, the year felt, to me, like a single sleepless night spent absorbing an interminable series of nightmares through my phone,” wrote Jia Tolentino in the New Yorker’s year end reflection. It wasn’t that 2016 was objectively worse than any year in recorded history, Tolentino noted. It’s that perhaps it was the beginning of the end, the start of a near-decade where it seems like things have only got worse, month by month, year by year. Things might have seemed bleak in 2016, politically and aesthetically, but we had no idea just how bad they were going to get. There’s no going back to that time, but watching a girl do a cut crease and bake her under eye, we can at least revisit it and revel in our then naivety, whilst also keeping the era that was the catalyst of our current turmoil at arms length.