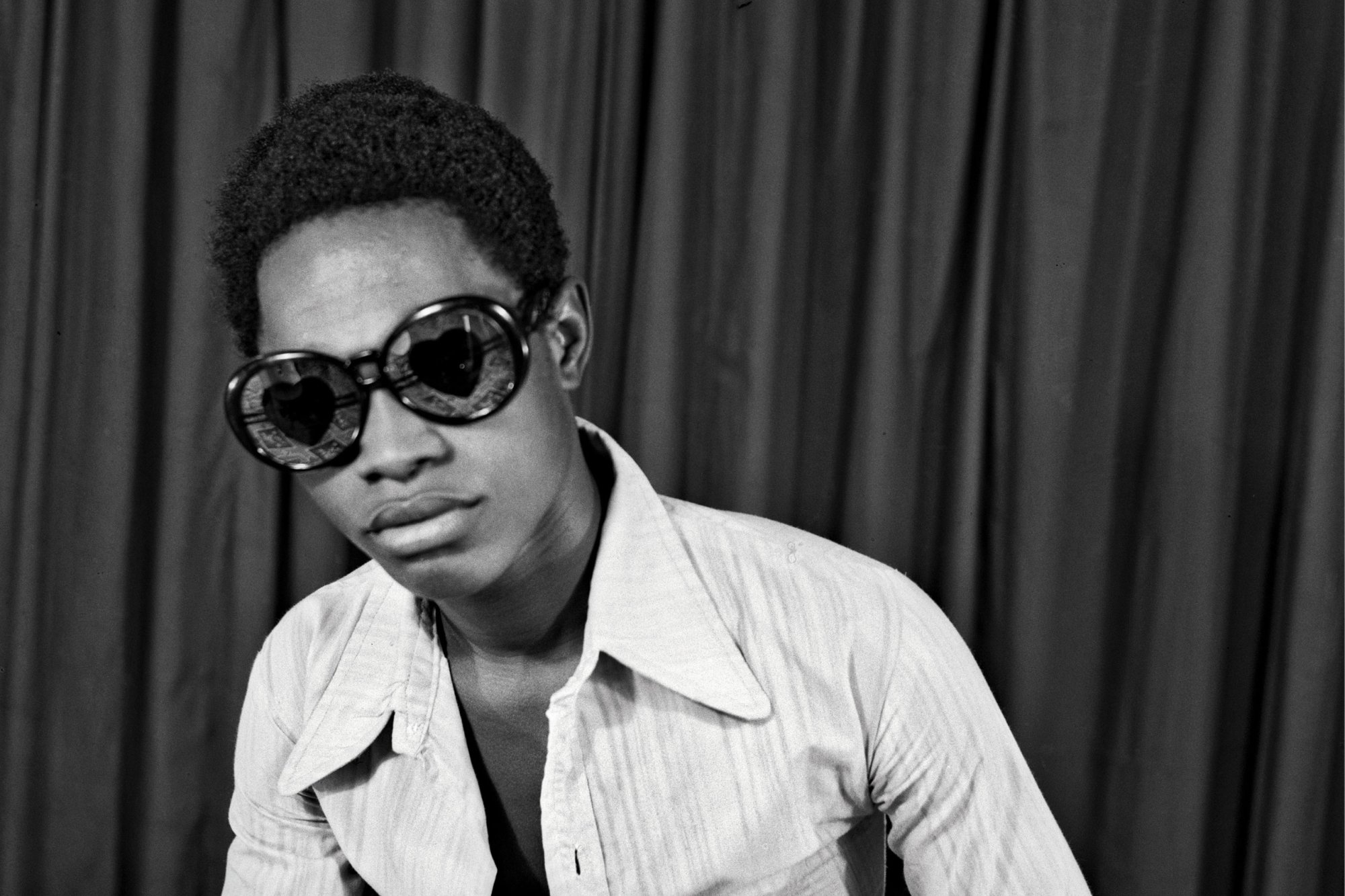

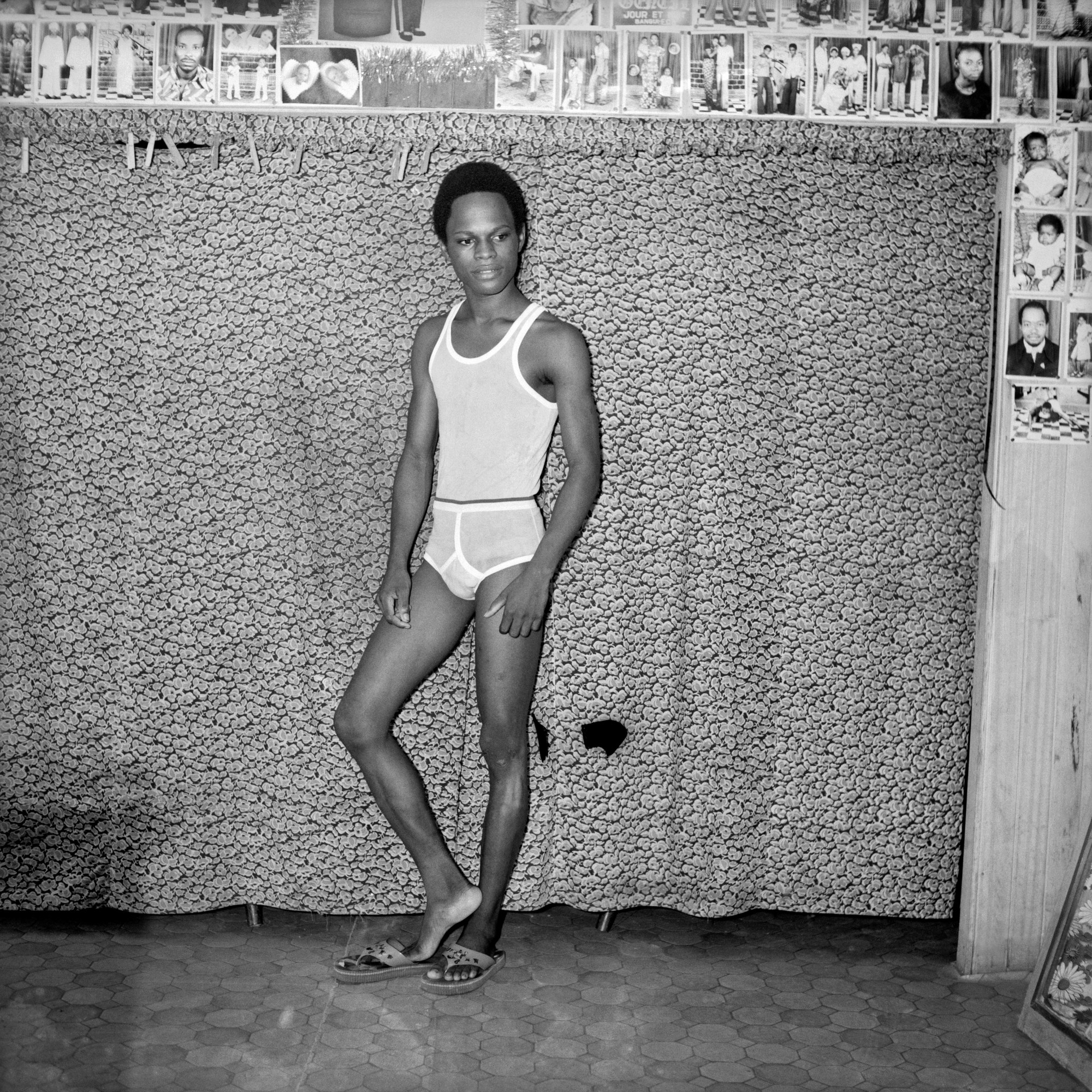

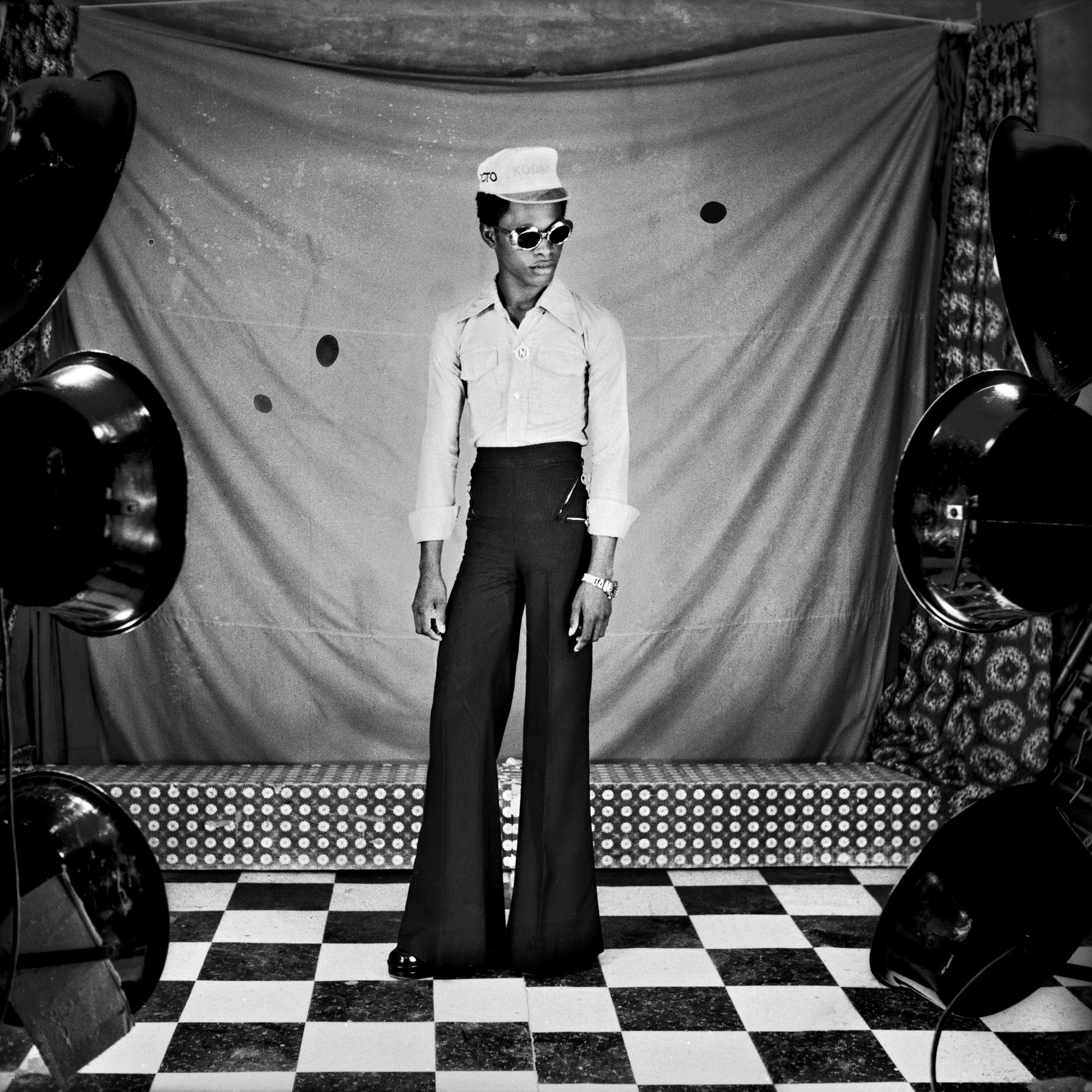

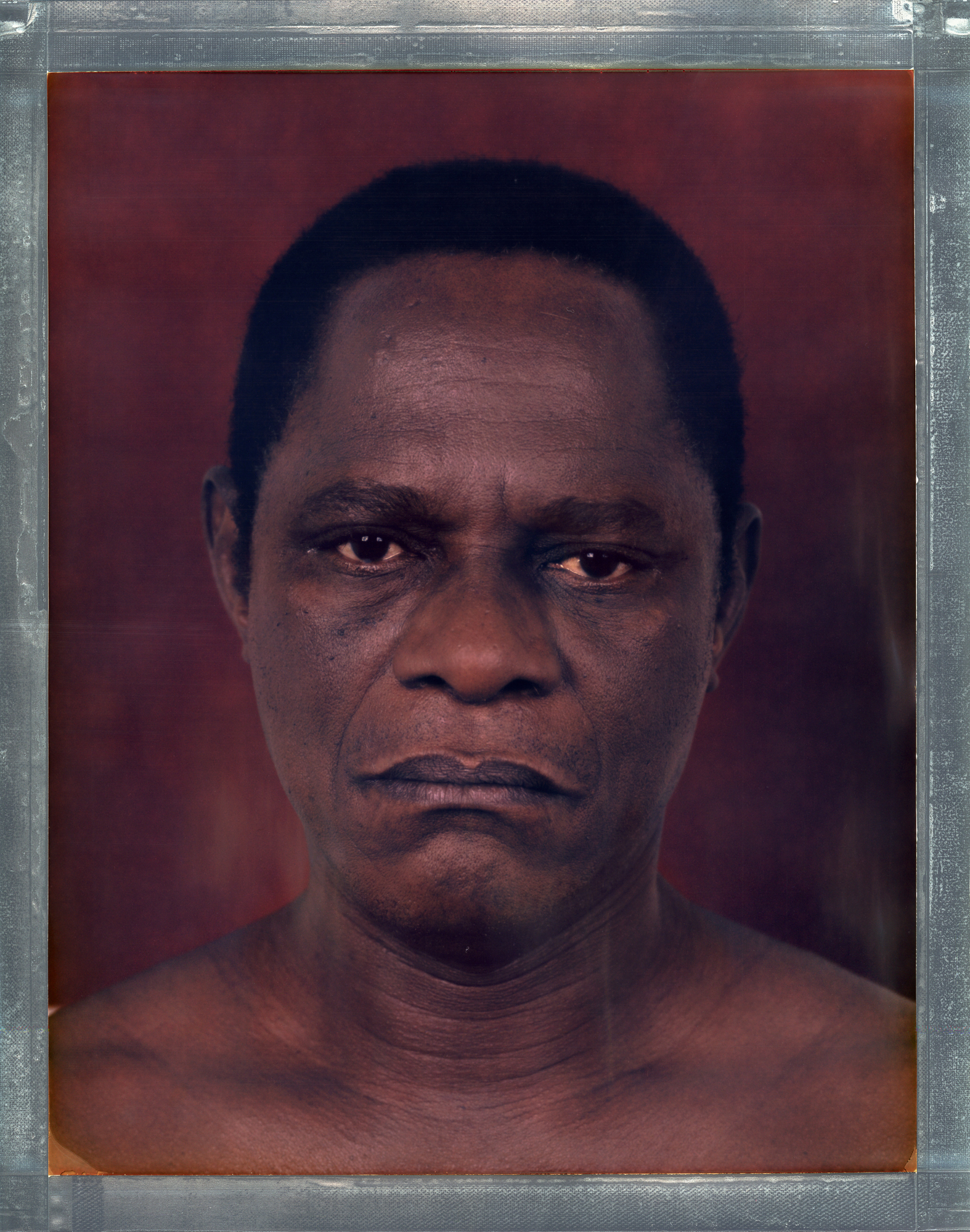

While still only a teenager, photographer Samuel Fosso opened his own photo studio. After shooting local clients all day, any unused film would be diverted to self-portraits. Born in West Cameroon, Fosso was raised in Nigeria by his grandparents, living there through the end of the harrowing Biafran War. In 1975, after relocating to Bangui in the Central African Republic with his uncle, he began a lifelong journey of using self-portraiture to probe themes of power, postcolonial identity, diaspora, and reinvention.

An exhibition on view through this week at Princeton University Art Museum, titled Affirmative Acts, highlights a small edit of his work; across the Atlantic, a wider-ranging eponymous retrospective is exhibited at Huis Marseille in Amsterdam (on view through March 12).

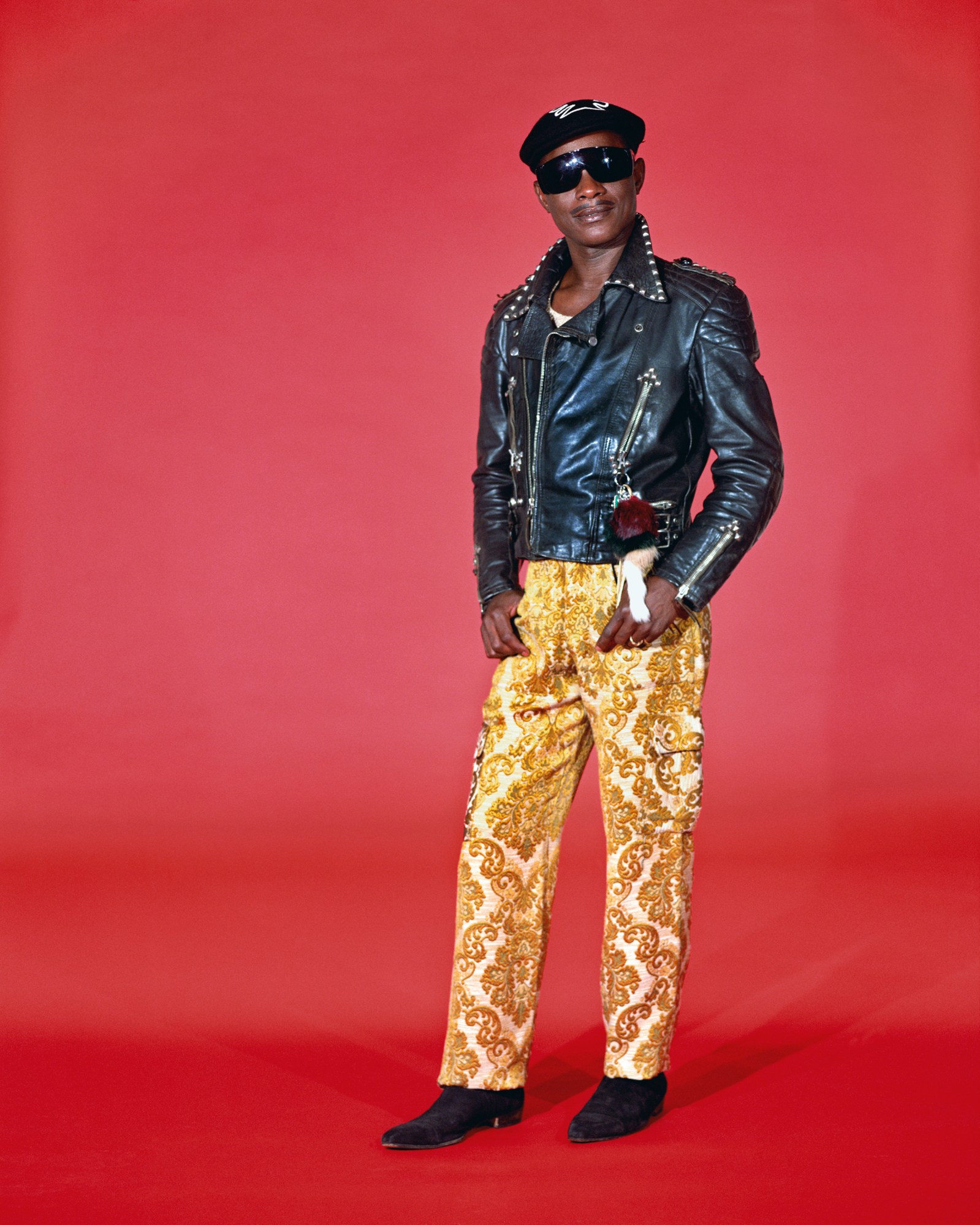

The clothes Samuel sported in the 70s were all his own, reflecting the sartorial trends of the time. Increasingly, over the course of his career, the photographer used his studio as a setting in which to explore cultural performance as well as forms of autobiographical representation, blurring between self and other through costumes and uniforms. Last year, Samuel returned to his roots when he participated in A Magazine Curated By menswear designer Grace Wales Bonner, as both dapper subject and skilled photographer.

We exchanged with Samuel about African heritage, iconography, and the uncanny parallels he shares with his favorite American photographer.

The title of the exhibition is “Samuel Fosso: Affirmative Acts.” What do you feel is affirmed through photography?

“Affirmative Acts” showcases my persistent desire, as an artist, to highlight important aspects of my story — but also, of course, as a reference to the fight against discrimination that affirmative action allowed. Through my self-portraits, I always highlight events and historical figures that are close to my heart. Photography began as a deeply personal way for me to affirm my identity ever since I was a teenager, and to represent myself to my family, who were living far away. At first, I simply wanted to show my grandmother that I was looking good and in good health: to affirm the power of life, especially following the handicap [he was born with paralyzed extremities, which his grandfather — a healer — corrected] I’d suffered from during childhood. Later, it became a simple affirmation of my plaisir de vivre—zest for life. And through my series, I wanted to make a statement on the African condition: regarding slavery, and the history of Western domination over Africa.

The exhibition is displayed within a university. Does this context make it possible to highlight certain more academic aspects of your work, or to situate anything differently?

It is extremely important for me to be able to present my work in an academic context, especially in the United States. My series have always had a historical component that I hold dearly: I often relate to the social sciences as much as to the arts. I always wanted young Africans in Africa, as well as people from the African diaspora, to see my work: to facilitate a better understanding of their own history. My series “African Spirits” connects different African communities around the world, and I hope the series will resonate with American students.

As an African-born photographer, how does talking about identity have a different resonance among African-American culture?

If you ask me, an African-American is an African. I understand the specificities of the history of each country, but what I personally seek is to highlight a shared heritage. African-Americans came from Africa, so I don’t want to differentiate. I invite viewers of my work to consider our origins in common, our Black ancestors — the same blood that runs through us — rather than thinking in terms of different histories. In many ways, the burdens of African-Americans are similar to those Africans who remained on the continent, given our relationship to Western domination.

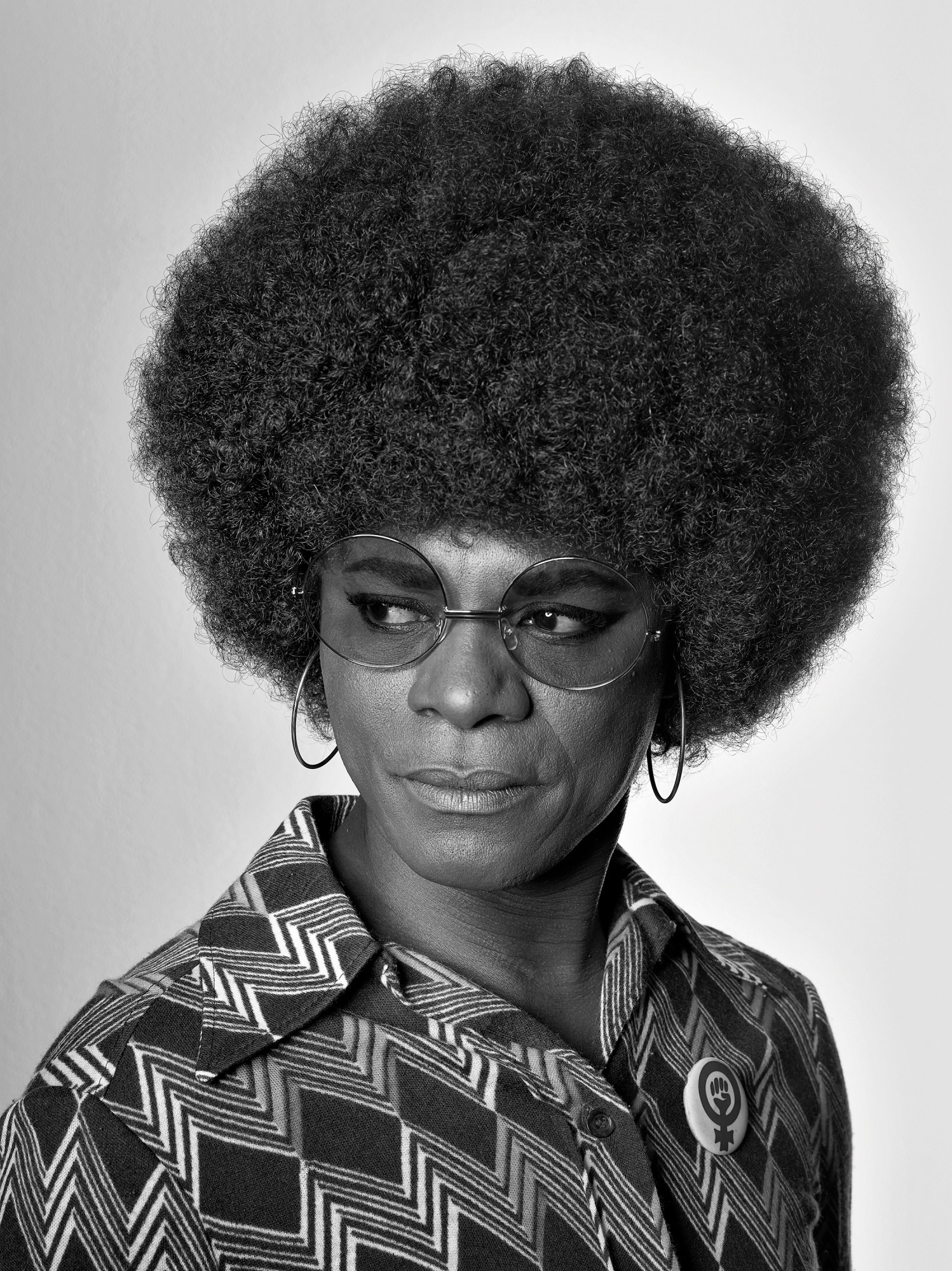

Can you talk about “The Liberated American Woman of the 1970s,” in more detail? How was it conceived? How have your conceptions of the theme of liberation and gender evolved over time?

When I made “The Liberated American Woman of the 1970s,” it was addressing the question of domination and of emancipation. When I represent a woman, my aim is a more universal scope, to talk about all Black American women, to evoke a bigger whole.

As for the creative process, the décor emphasized slavery motifs of bananas, coffee, plantations. This background contrasts with the character in the foreground who — through the posture and the clothes — presents a liberated attitude. I chose to dress her in Western fashion to confront these contexts and because, during the second half of the 20th century, clothing was one of the first ways women could feel like men.

But we can’t summarize everything through questions of liberation and gender.

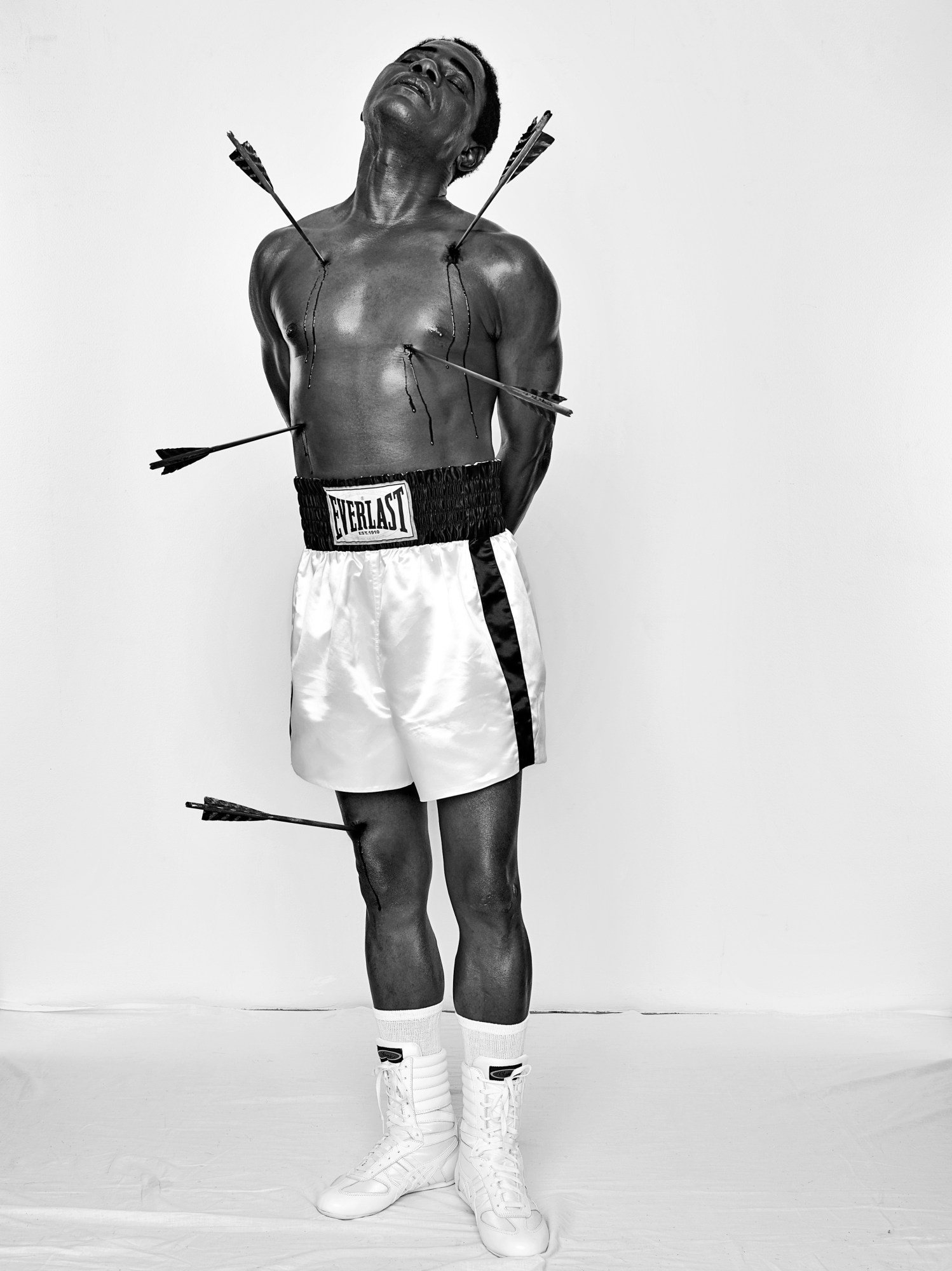

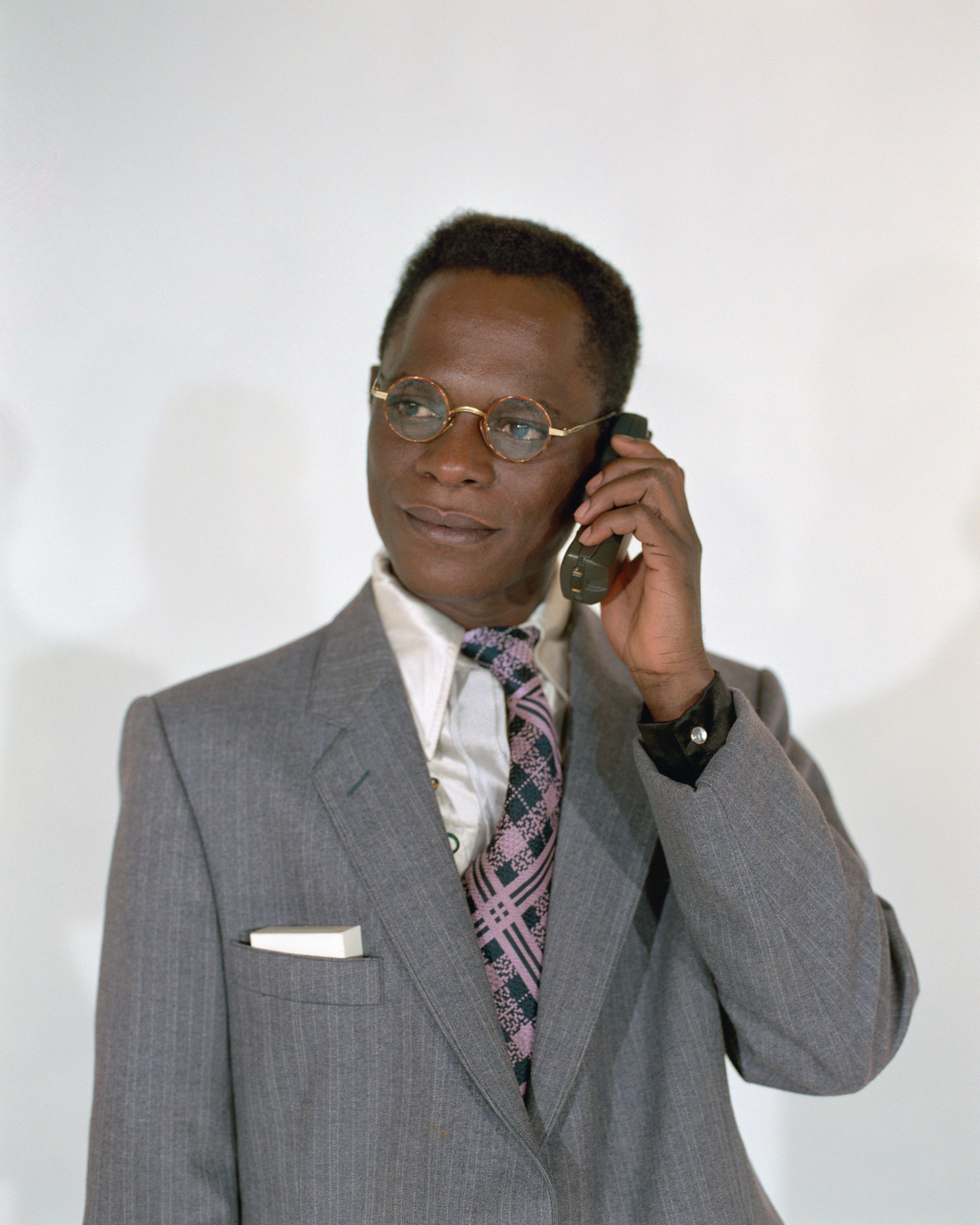

Having hailed Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Angela Davis, and Muhammad Ali in the 2008 “African Spirits” series, amongst other prominent figures from 20th-century Black liberation movements, how does showing these portraits in the native lands of these figures change or expand these references?

It’s very important for me to show these portraits in the native country of these figures. Indeed, these people, through their journey, fought for civil rights, yet we don’t talk enough about them. The series are also a way for me to address them to the new generation, so that they know the characters of yesterday who allowed them to be freer today than their ancestors were. It’s extremely important to me that contemporary Black Americans be familiar with these key historical figures.

In the American panorama, which photographers do you like or follow?Cindy Sherman, whose self-portrait work I obviously love. We started at almost the same age, in the same years: she uses her own body to tell stories like I do. The similarities are countless. But I didn’t know her at all when I started, and yet, it’s as if she was the American incarnation of what I was doing on my side in Africa.

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist, Jean Marc Patras Paris and The Walther Collection.