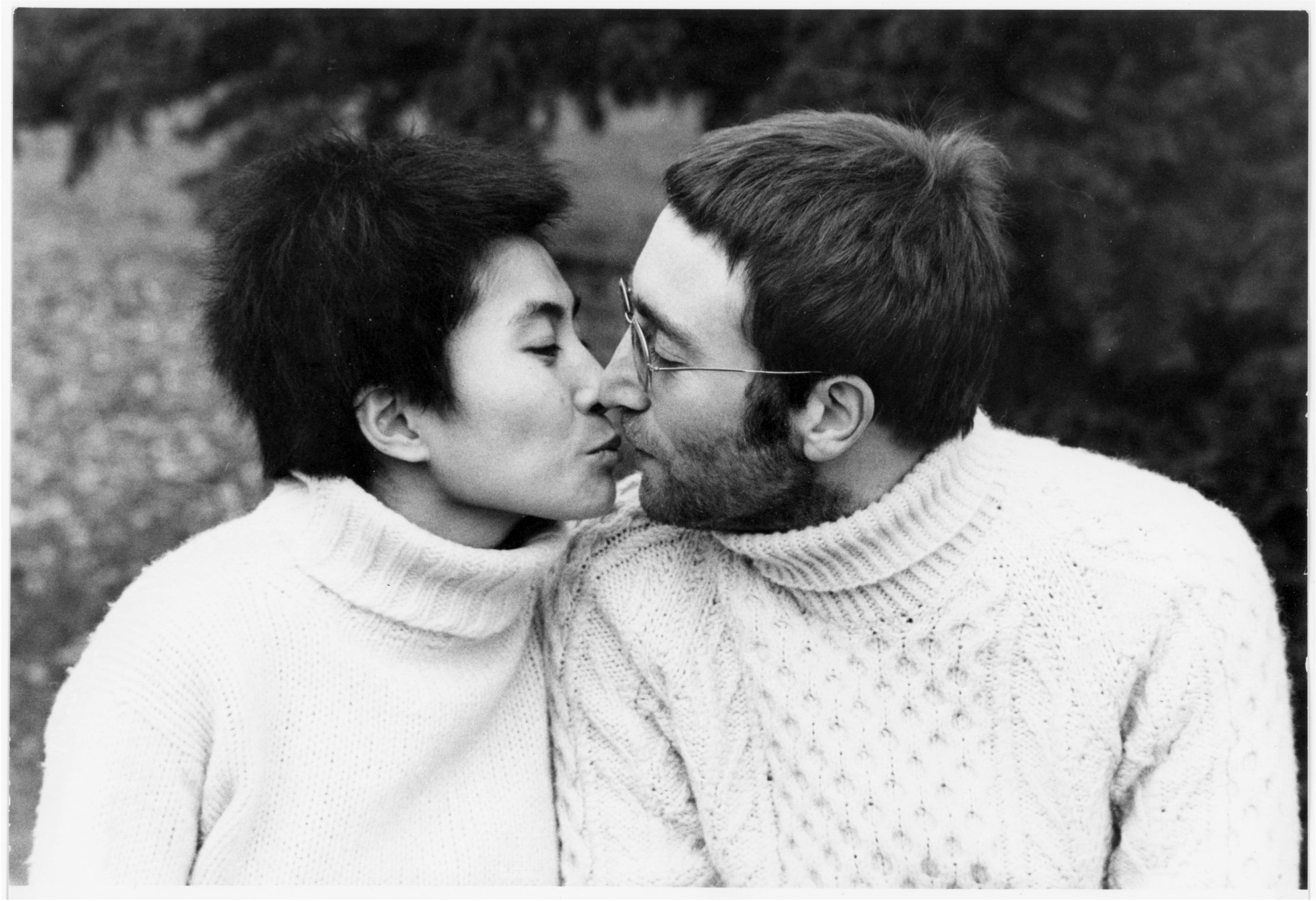

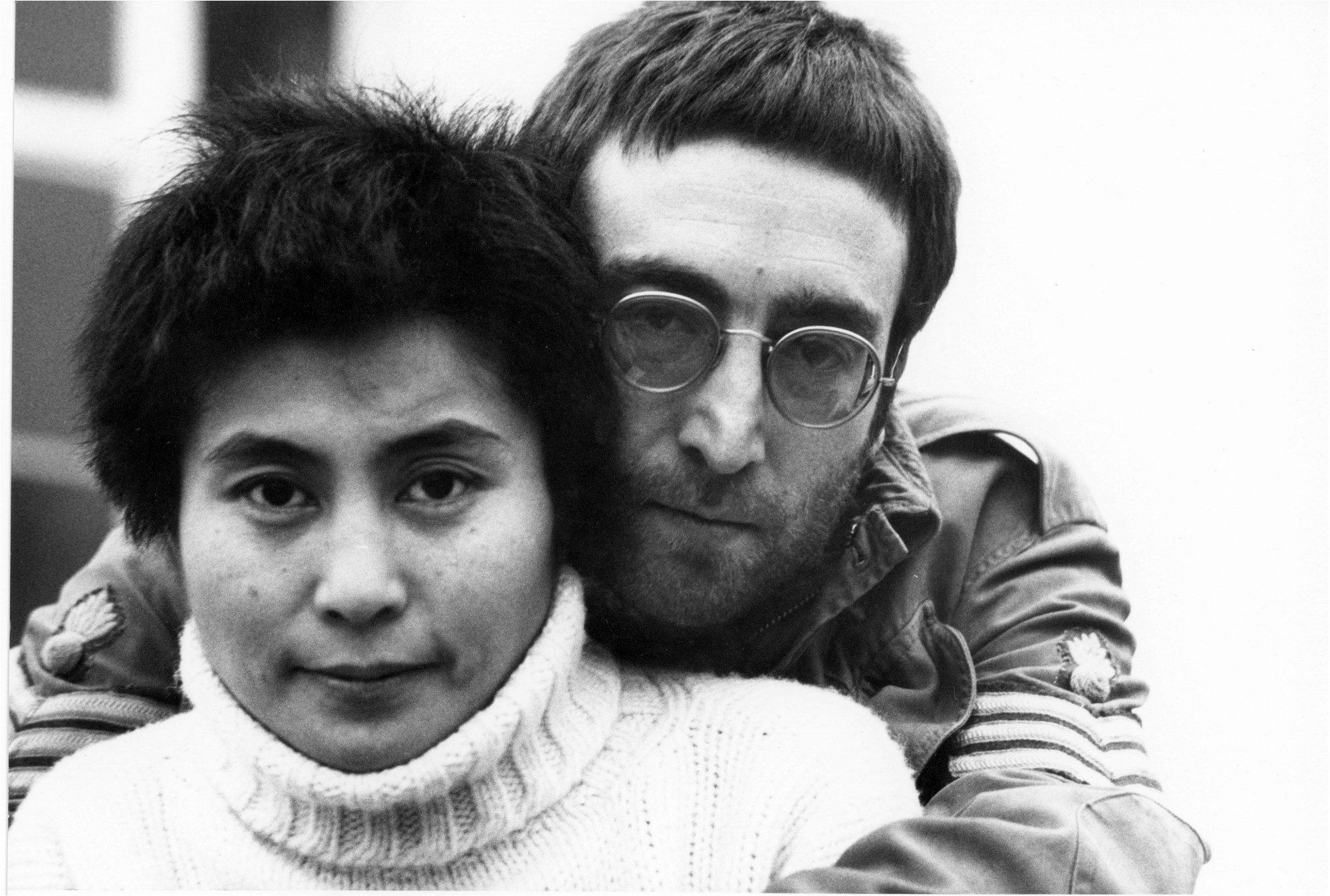

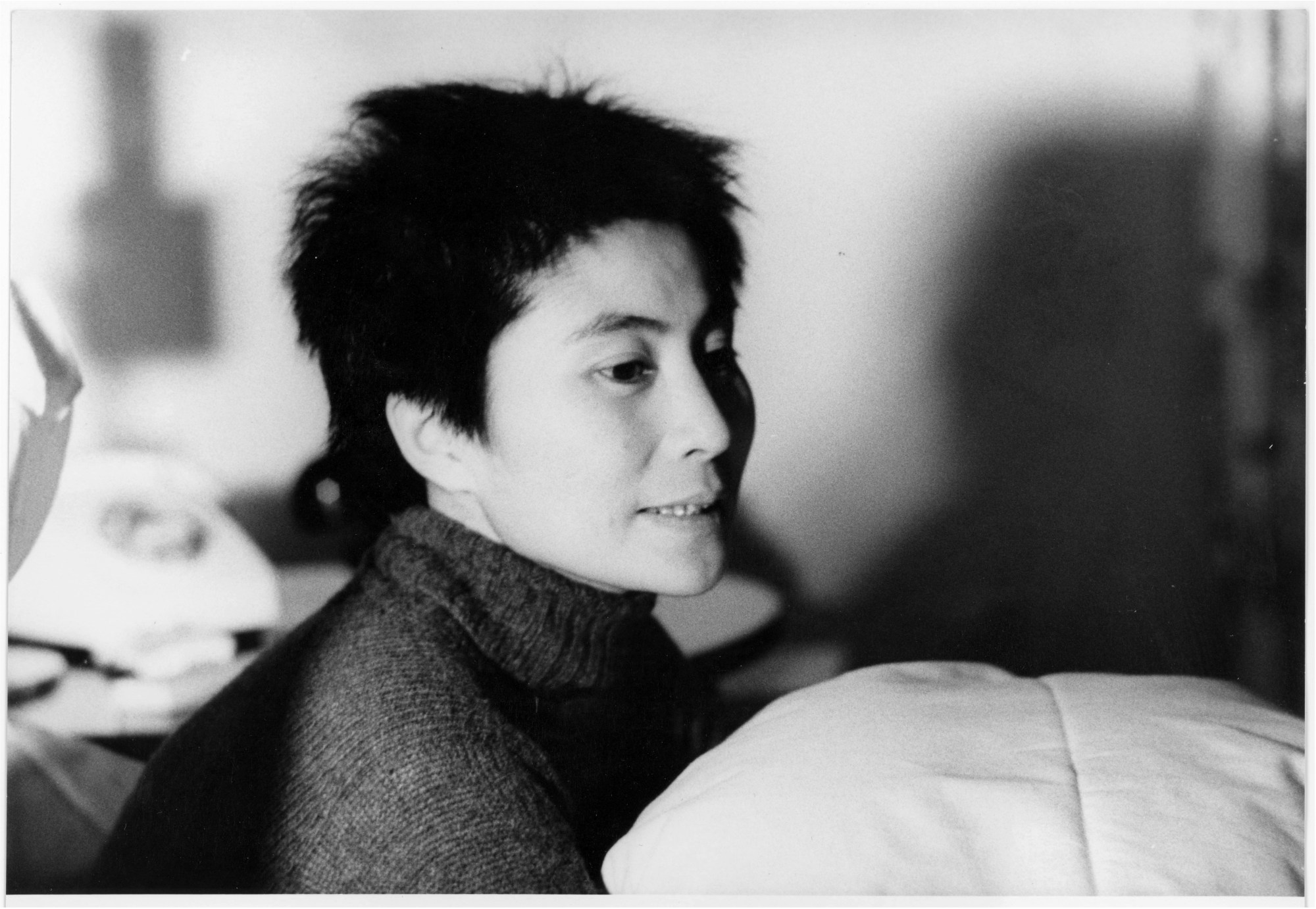

In January 1970, John Lennon and Yoko Ono returned from a trip to Denmark with short hair, a symbolic gesture of a new phase in their lives. John had secretly quit The Beatles and was beginning work on music for his debut solo album, Plastic Ono Band. “There was an immediate request from the media to get pictures of the Lennons sporting their new art school look,” Richard DiLello, who worked at The Beatles’ Apple Records, tells us. “I was in the press office with Derek Taylor and as the requests for photo sessions with them continued to come in, I asked him, ‘Do you think John and Yoko would let me photograph them?’”

Richard, who had traded his Vox amp for a friend’s Nikon F with a 50mm lens two years prior, had a natural eye for photography but limited technical knowledge. John and Yoko agreed to the shoot. Two days later, they invited him over to Tittenhurst Park, the early Georgian country house they lived in for all of two years before moving to New York in 1971.

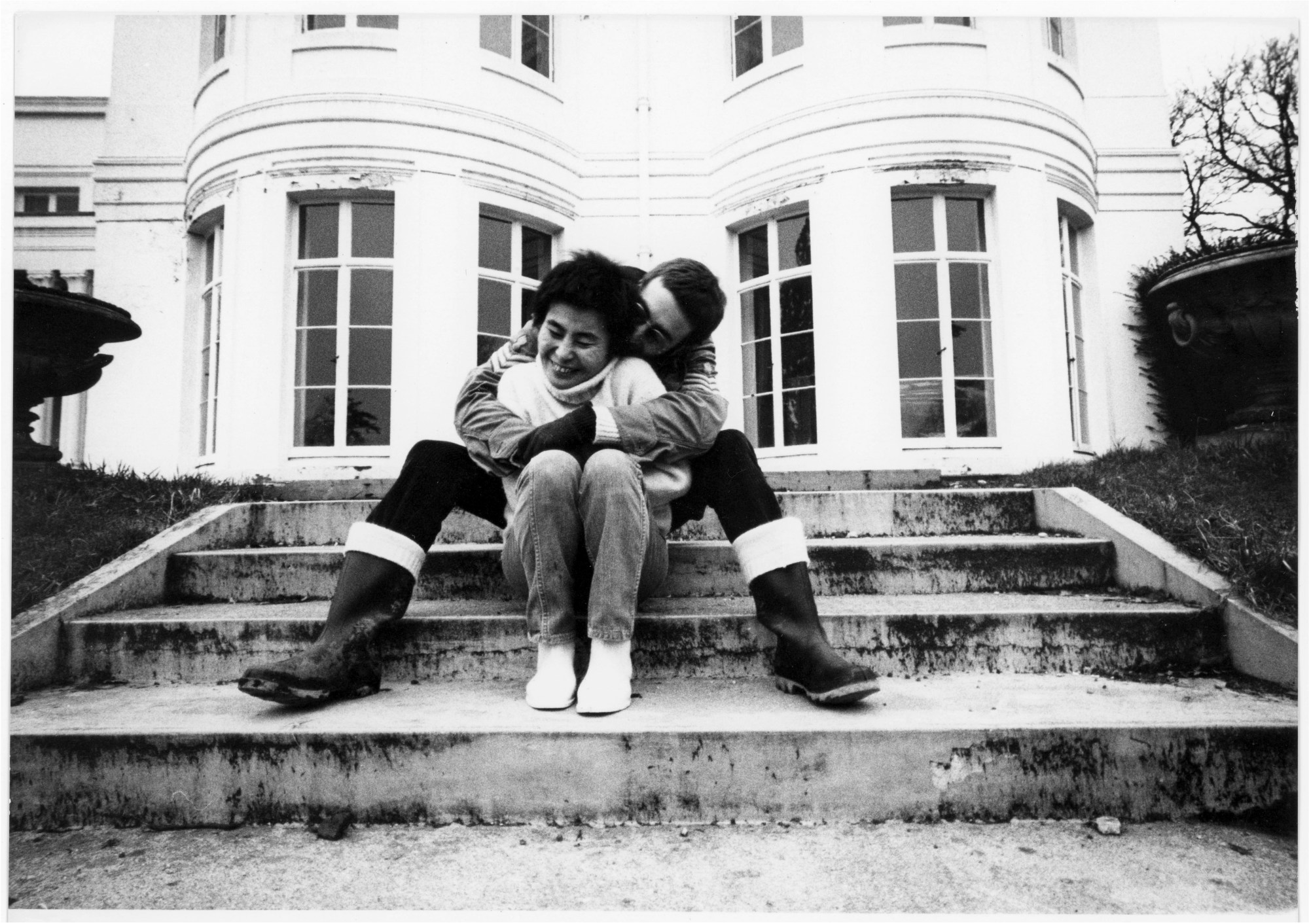

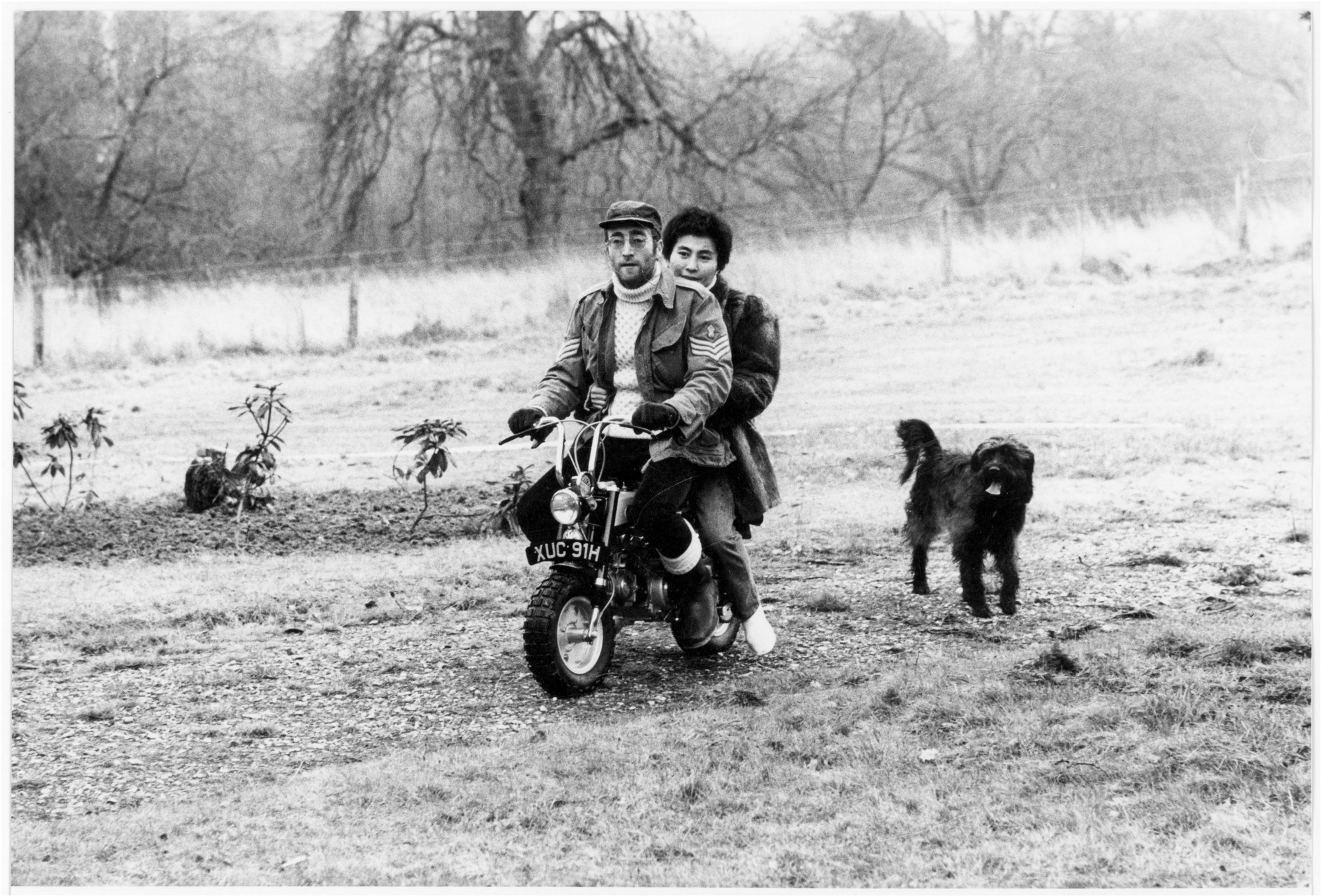

It was a cold, grey day — 31 January 1970, to be precise — when one of the Apple Records chauffeurs drove Richard over to the 72-acre estate near Ascot, to capture the pop culture icons up close and personal, in and around their vast home. “The great thing about photographing the Lennons was their ease and comfort,” Richard remembers. “I also wasn’t a stranger, which helped. I didn’t need to give them much direction, because they were the directors of their own lives. I shot most of the session on black-and-white Ilford film, because it was a black-and-white world.”

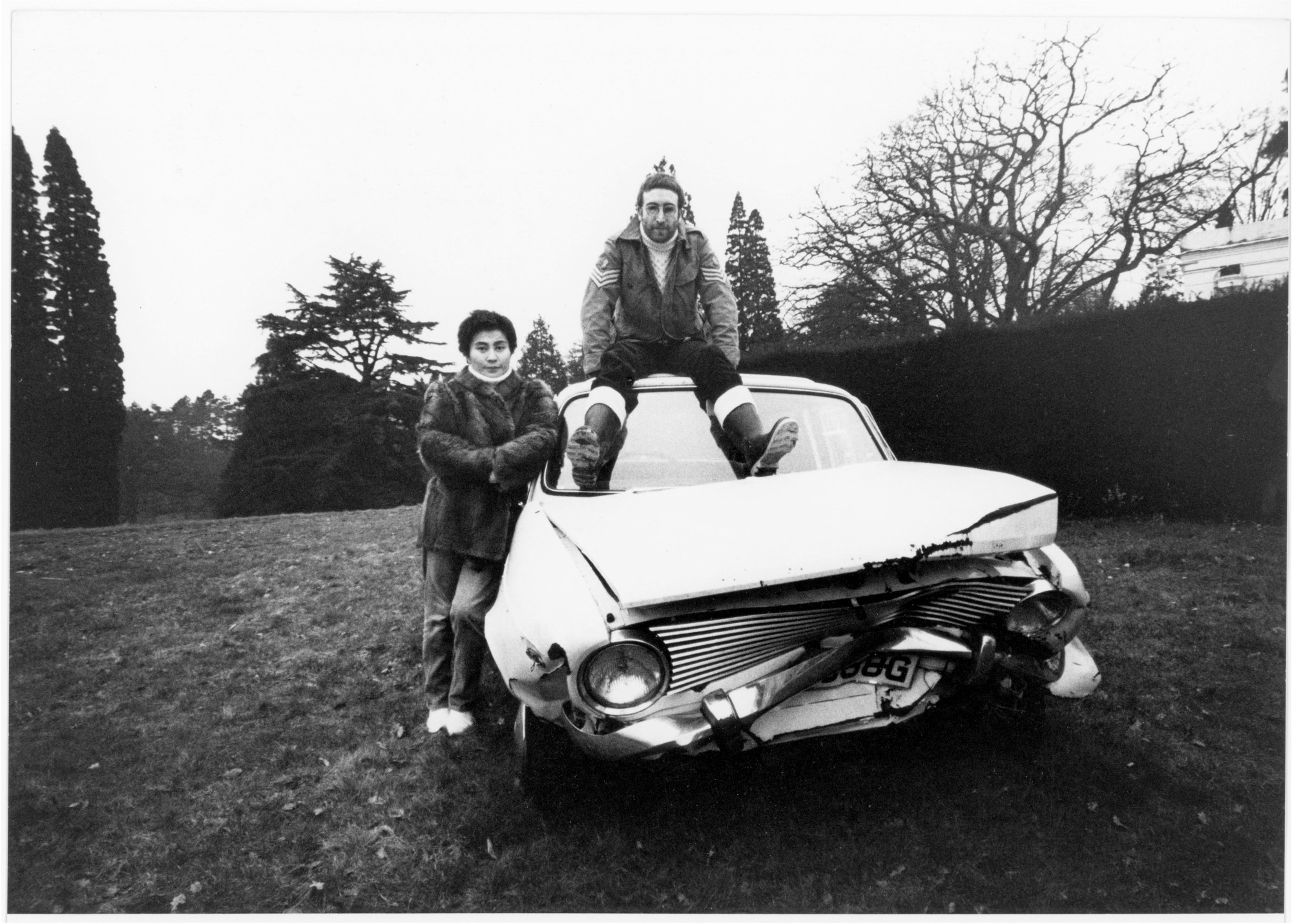

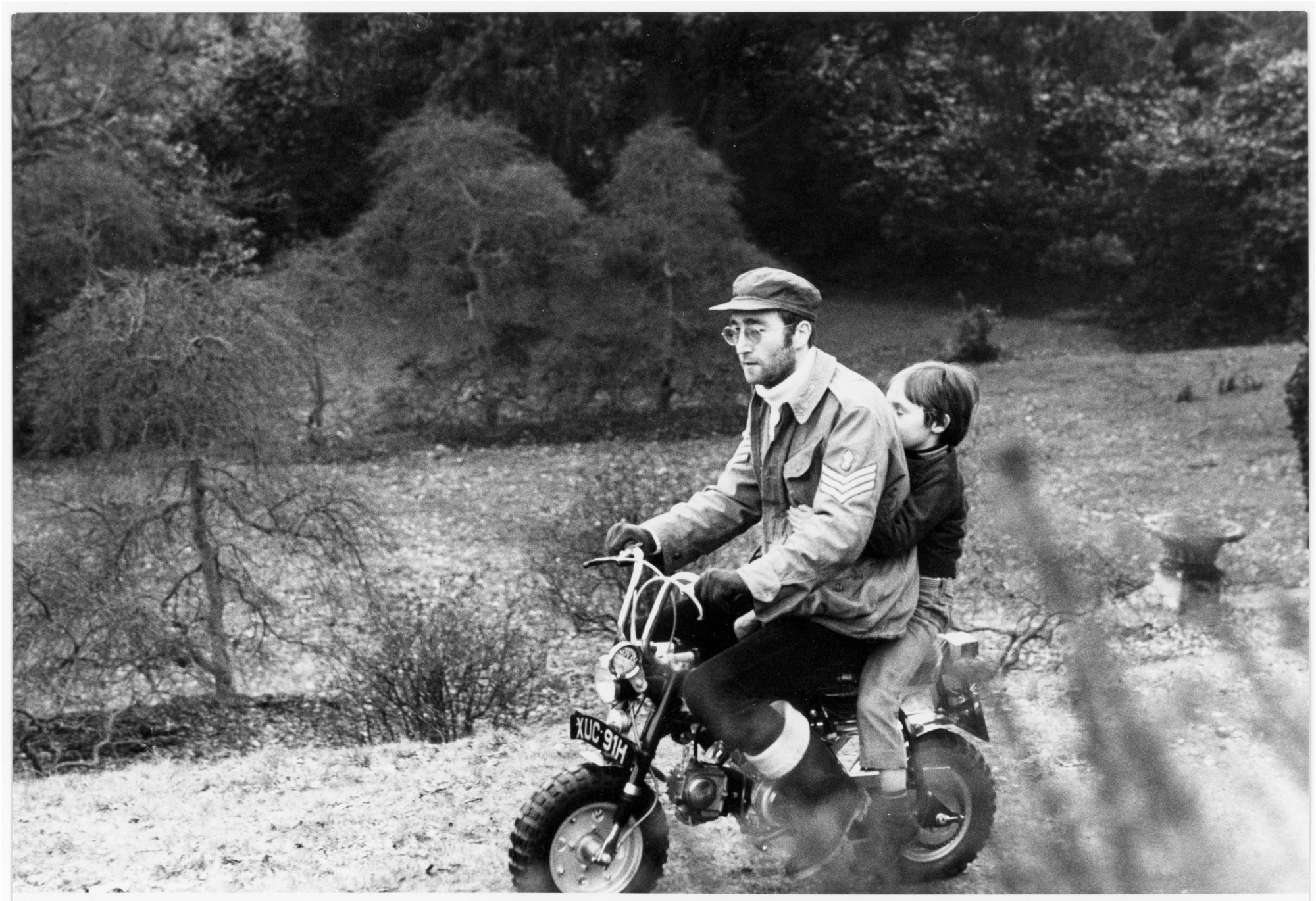

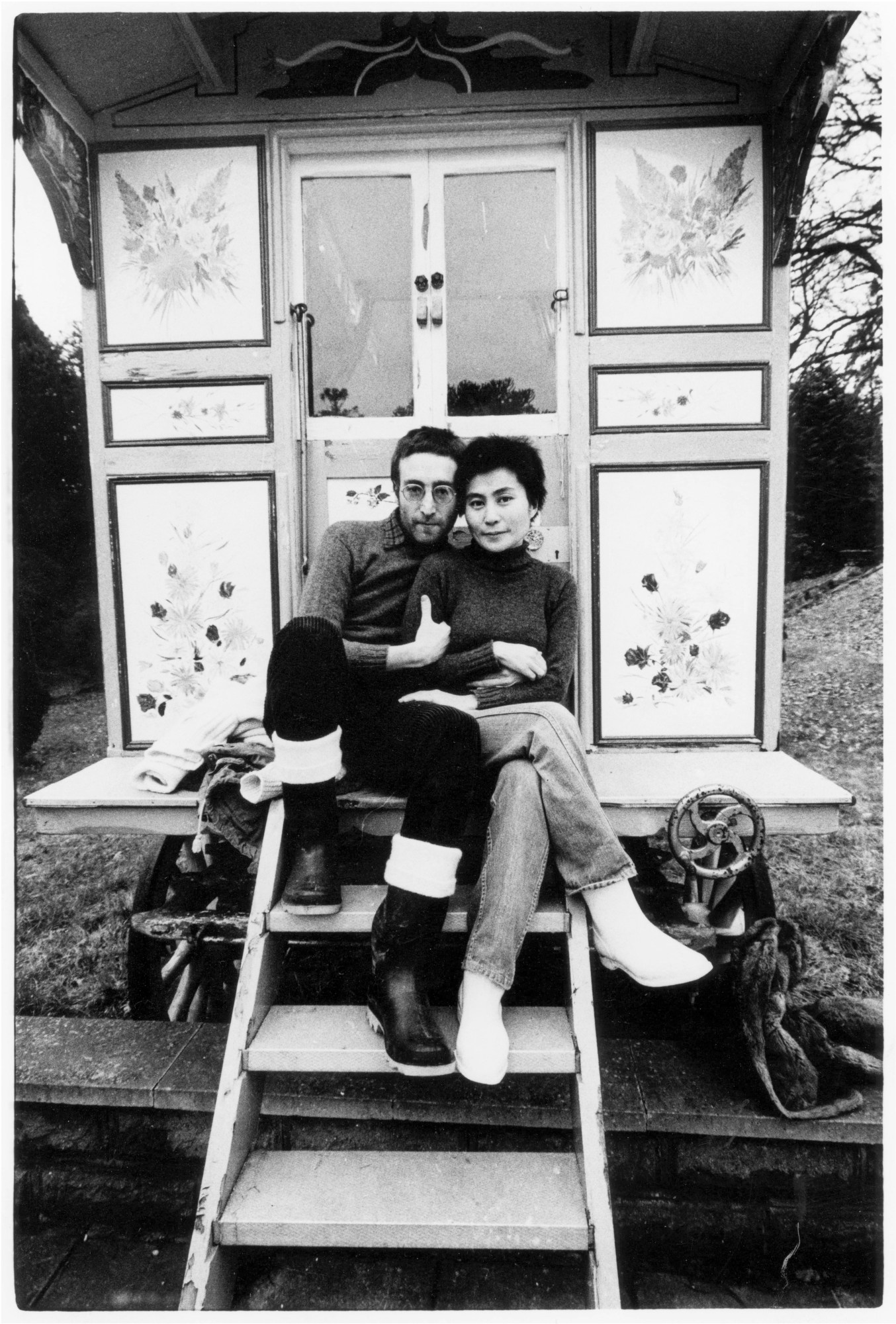

The photos follow the couple through the estate; embracing by their pond in matching roll-neck sweaters, walking through the trees with their dogs and sitting on the steps of the famous Sgt. Pepper caravan (“the only object on site that wasn’t black-and-white”). They also capture John riding about on a mini motorcycle with his son Julian — who was visiting for the day with one of his friends — and posing atop their Austin Maxi, a car that John had crashed during a family holiday in Scotland. “As Derek Taylor told me — with great affection — ‘John was never much of a driver to begin with’,” Richard says. “Rather than send the wreck to the junkyard, John and Yoko turned it into a piece of conceptual art.” Of course they did!

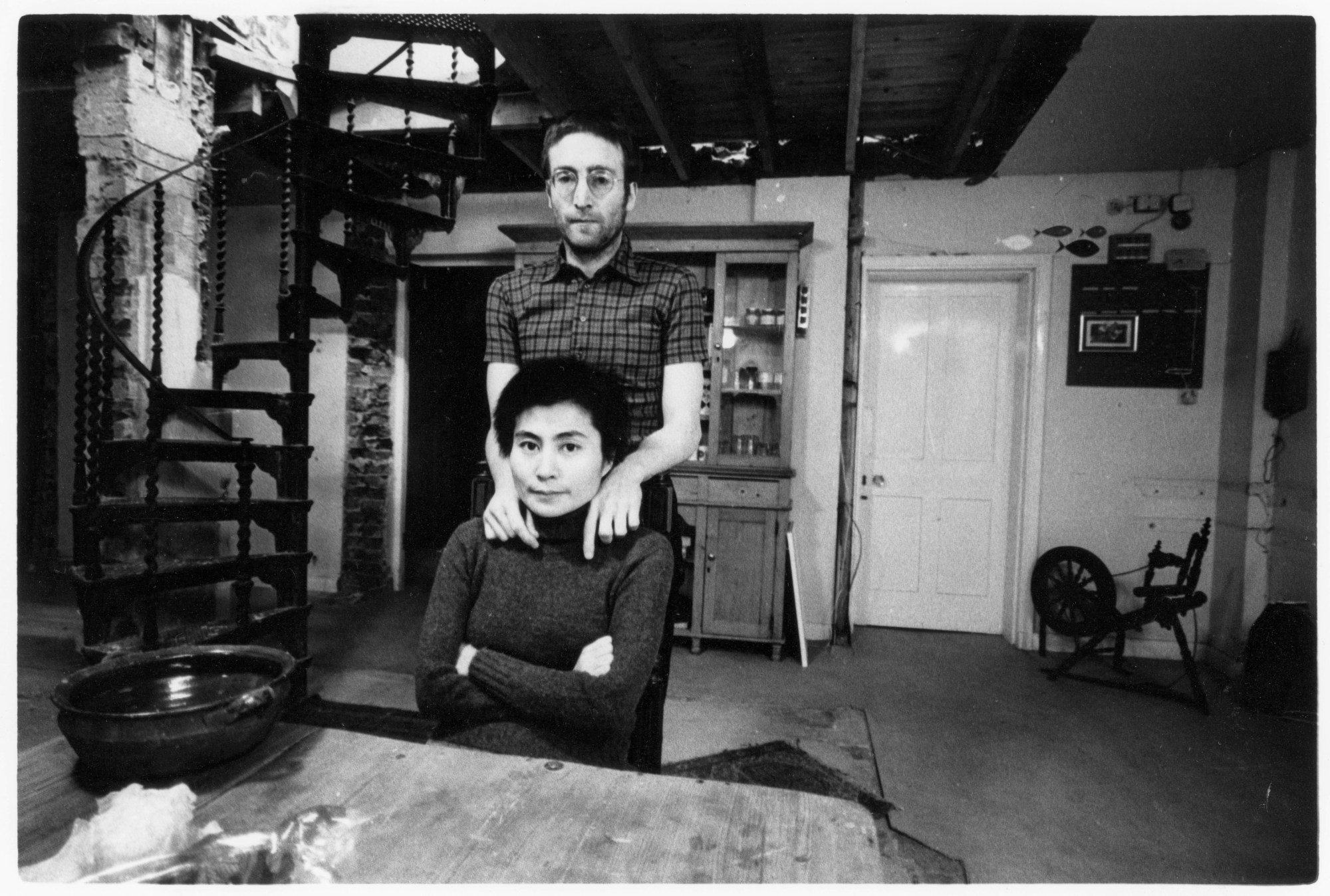

“After the outdoor session we went inside, Yoko made us salad for lunch and we did some more [shots] in the kitchen and upstairs in their bedroom as they watched television,” Richard says. “It all felt very intimate and low-key, no pressure. The entire session was shot with available light, because I didn’t own a flash, or know how to use one.” He notes that despite this and the fact that he was just “the kid from the office,” the couple were very kind to him and made him feel comfortable. “It was always exciting to be around John and Yoko,” he says. “Even if they were just drinking a cup of tea or lighting a cigarette, it felt like an event, an art happening.”

Fifty years after they were taken, Richard’s photographs of John and Yoko are finally being released as part of John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band — The Ultimate Collection, a compilation of 159 tracks (new mixes, never-before-heard demos, outtakes, jams, live session recordings) as well as a book full of lyrics, memorabilia and the images in question. The project is being released by Yoko Ono Lennon to celebrate the anniversary of John’s debut solo album this April. On release, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band sounded nothing like the work of one of the world’s biggest popstars. It was haunting; a deeply personal artistic exorcism with which John let out the hurt he had carried with him since childhood. It’s a record that Richard remembers well.

“When the Plastic Ono Band album was released and I heard it for the first time, it made perfect sense in its blatantly anti-commercial roar,” he says. “It was the album John Lennon was born to make in his post-Beatle life; it was the inevitable meeting the unavoidable. It was painful to listen to because it was the definition of ‘pain’. There would have been no need for Primal Scream Therapy [which John and Yoko had been practising with an American psychologist] if there had been no primal wound to begin with — a young, sensitive boy abandoned by his mother and father when he needed them most. And then the damaged, discarded boy becomes the most famous musician in the world and everyone wants a piece of him. John’s three best friends and bandmates all came from intact, loving families. John didn’t. And he paid the price.”

Richard, who was still working for Apple Records when the solo album was released, has a theory as to why the Plastic Ono Band album was as revolutionary as it was. “No other musician of John Lennon’s stature in the 20th Century could have, or would have dared to, open up and let all the screaming demons come raging out the way he did,” he says. “Not Dylan, not Leonard Cohen, not anyone. That said, the album still swings. It’s still rock ‘n’ roll. It was proto-punk, proto-grunge, proto-everything confessional, which is the heart of all great music and art.”

John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band – The Ultimate Collection is out 23 April and available to pre-order now.

Credits

Images courtesy Richard DiLello