In 1976, photographer Sunil Gupta and his boyfriend moved from Montreal to New York City during the golden age of queer nightlife and creativity. In the years following the Stonewall Uprising, the West Village had become the Mecca of the LGBTQ scene, welcoming people from all walks of life into a flourishing bohemian paradise.

“I felt very at home in New York, more than I felt in Canada,” Sunil recalls. Born in New Delhi, Sunil arrived in Montreal as a teen in the 60s, enrolling at a local high school to find he was the sole Indian student. Without a community, he felt out of place — until he discovered the local LGBTQ scene. He joined a gay student society involved in activism and embarked on his first foray into photography, shooting small items for their newsletter.

“Gay was something to latch on to, a lifeline [in Canada],” he recalls. “But in New York, diversity was everywhere and it was just fine to be different. Even though I was often mistaken for something else, usually Puerto Rican, I didn’t feel out of place. I was in a city where things had meaning. There was a buzz. You were amongst people who made things, whether it was writing, painting, photography, or film. I was going to galleries, museums, and events, meeting people who introduced me to a new world.”

Sunil abandoned his plan to pursue an MBA and began taking non-degree classes at the New School. Here he met a collector and became inspired by how people integrated art into their everyday lives. “I decided to join in. I was naturally inclined to take pictures of people and street photographs,” he says of the impetus to make the Christopher Street series, which took root as Sunil observed how quickly New York street life changed in just a matter of blocks.

At the time, Sunil was living in Chelsea and was increasingly drawn to Christopher Street, the heart and soul of New York’s queer community. “It was my tribe, and it became a place I was always coming back to,” he says. “I was shooting everything that moved without a big plan. Then I shot some Super 8 film but never got anywhere near movie making.” The work largely went unseen until a few years ago when Sunil began making scans. The films are still in the archival box, awaiting rediscovery.

While Sunil pursued photography, his boyfriend was training for a banking career at JP Morgan. Once the training was completed, he transferred to London to begin work during the summer of 1978. Sunil joined him, arriving just in time for the UK’s Winter of Discontent, where British trade unions organised more than 2,000 strikes nationwide to protest the Labour government’s imposition of a 5% wage increase limit. Streets piled with garbage, hospital services were limited, and gravediggers put their shovels down. The following year, under Margaret Thatcher’s leadership, the Conservatives capitalised on the unrest in their rise to power.

After settling into what they thought was a gay enclave, Sunil recalls slowly discovering that “there was no such space in London.” Although private homosexual acts had been decriminalised between men over age 21 in 1967, they began targeting the public same-sex encounters under the Street Offences Act of 1959, an anti-prostitution ordinance.

“The government criminalised cruising, which they legally equated to curb crawling and soliciting,” Sunil says. “They used it very aggressively in London so the public was still fearful. On the whole, there weren’t many people visible on the street. Clubs were hidden away because you could be arrested. It was like how I imagined New York in the 1950s to be. It was difficult to find my place.”

To make matters worse, Sunil arrived in London just as the National Front were openly targeting Afro Caribbean and South Asian immigrants. Following World War II, the British Empire collapsed as colonised lands sought their freedom, spawning a global independence movement. As the economy declined, the extreme right-wing used racism and xenophobia to expand its power base. “I walked into this phenomenon called ‘Paki Bashing,'” Sunil says. “They didn’t just call you names, they chased you down the street. It permeated everything, including the gay scene. It was hostile to people of colour, so there weren’t many visible.”

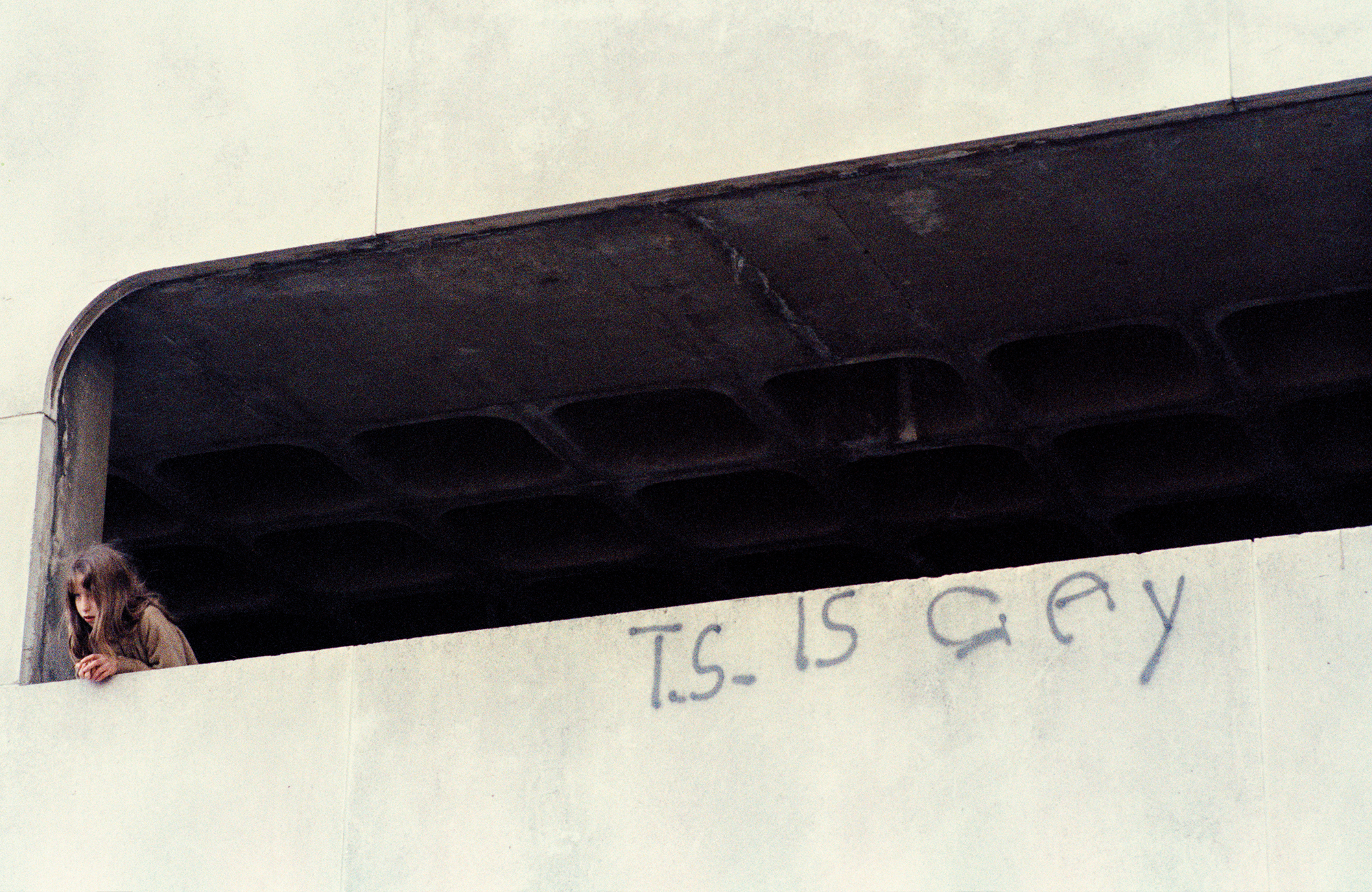

Sunil turned to street photography once again to navigate his experiences of life in a new city. While pursuing his MA in photography at the Royal College of Art, he began searching for London’s equivalent to the West Village, photographing small concentrations of gay life around Earl’s Court, King’s Road, and the West End. “I was carrying my camera everywhere because I was in school and could spend all my days wandering around. Initially, I was trying to repeat Christopher Street and find a neighbourhood that would reflect me in some way.” This work forms the basis of his new book, Sunil Gupta: London ’82 (Stanley/Barker).

But things didn’t quite work out the way he hoped. “People in London didn’t like me to approach them the way they did in New York. They didn’t want to make eye contact. They would pretend I wasn’t there and not acknowledge what was happening.”

Adapting to this impermeable demeanour, Sunil literally and figuratively stepped back for a wider shot of London street life in the early 80s. Although he wasn’t trying to make a statement with the pictures, he does just this by capturing the look and feel of public life. “I gave up the private focus on subcultures because they weren’t visible and began to shoot all kinds of people that caught my eye: people of colour, pensioners, Sloane Rangers, kids. It’s a much broader brushstroke than the New York pictures and, in retrospect, it has become this moment in time. 70s Britain had been tough and led to a very had line conservative government under Margaret Thatcher,” he says.

“At the time people weren’t able to voice opinions about race, sexuality, and gender. We all had to just live with [the status quo] and accept it as normal. You just expected to be harassed, it was part of everyday life, and it didn’t occur to anyone to object. I was much less critical of what was around me so that, even though I was shooting people of colour or women, I wasn’t thinking of them the way I might if I were to do this now. I would be much more aware of the context now.”

Credits

All photography Sunil Gupta