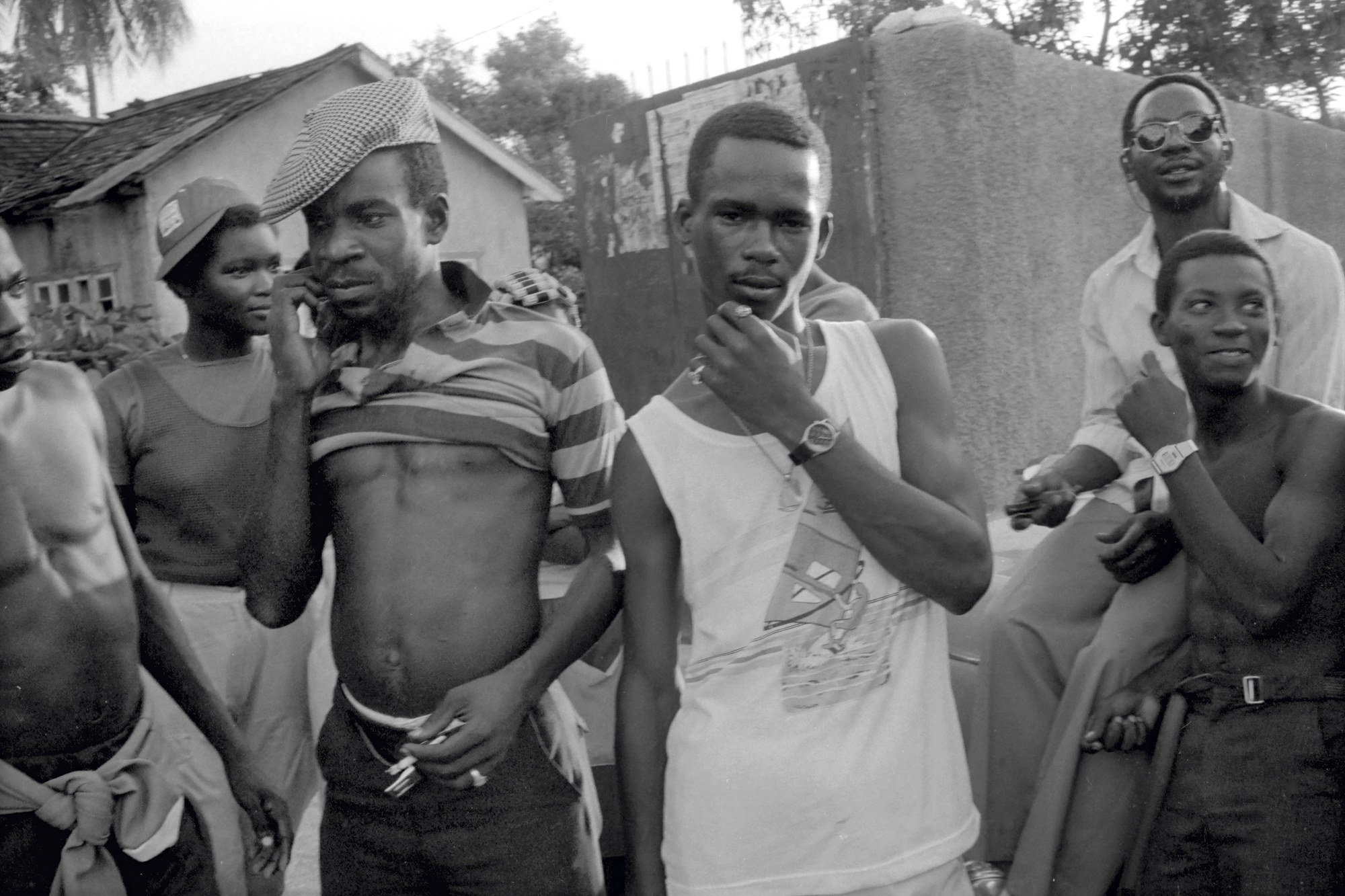

On a hot and humid night in April 1986, British photographer Wayne Tippetts ventured into the Kingston yard of singer and producer Lincoln Barrington “Sugar” Minott (1956–2010), where he encountered Jamaican sound system culture for the very first time. “It was literally a sonic vibe,” he says. “I remember it was very dark and the intensity of it, just being enveloped in ganja.”

Then shots rang out into the night. An off-duty policeman gave a proper gun salute, firing rounds off his M16 rifle into the air not far from where Wayne stood. “It was quite a shock, but it certainly added to the atmosphere,” he says.

Armed with just a Leica, Wayne made his way through the dark, his eyes acclimatising to a realm few outsiders had seen. As a social documentary photographer by training, he serendipitously stumbled upon a hypnotic subculture taking the underground by storm. Having no camera flash, Wayne quickly improvised, grabbing a bright, halogen lamp and handing it to a friend so that he could freely shoot a single roll of film.

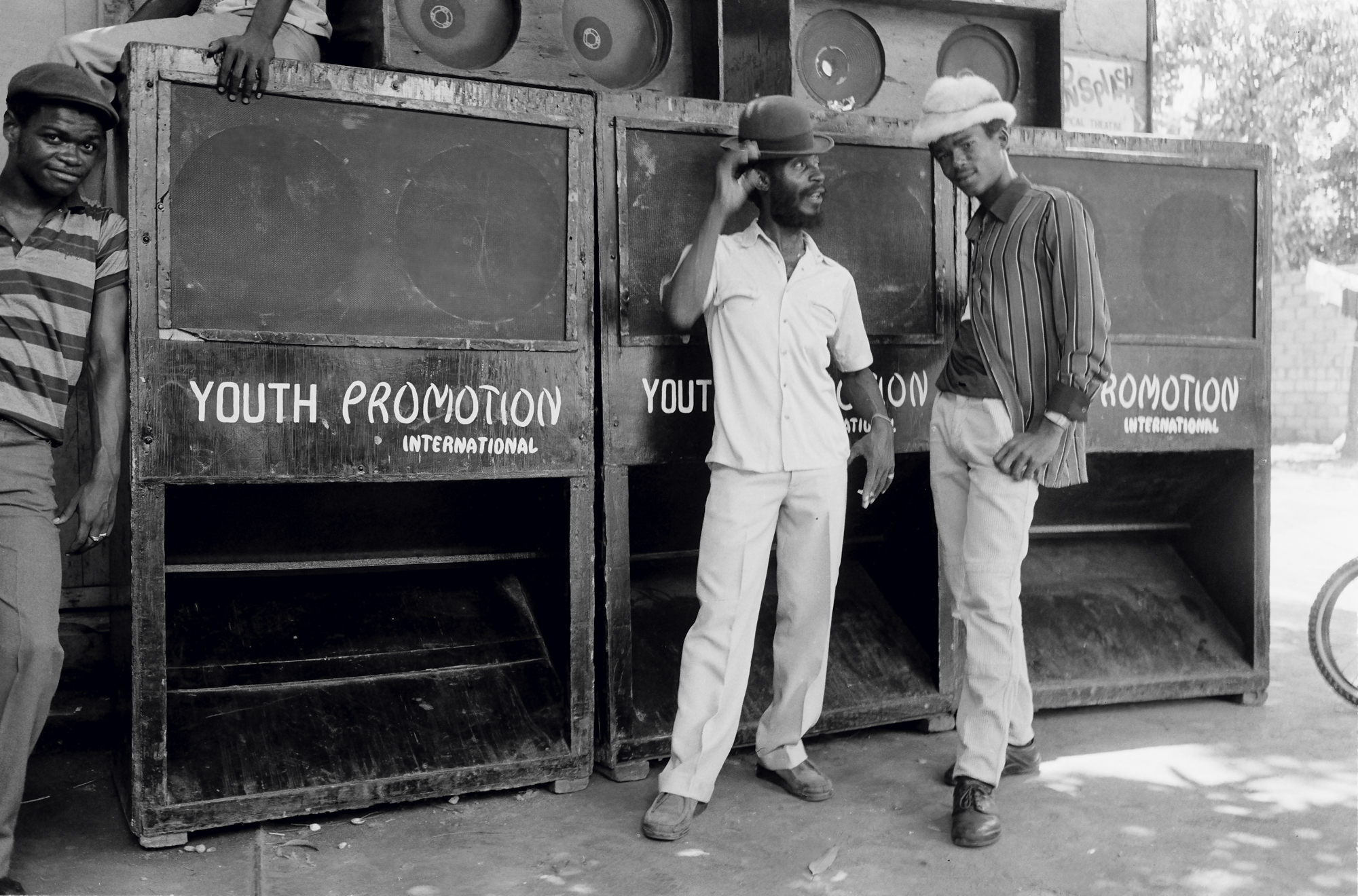

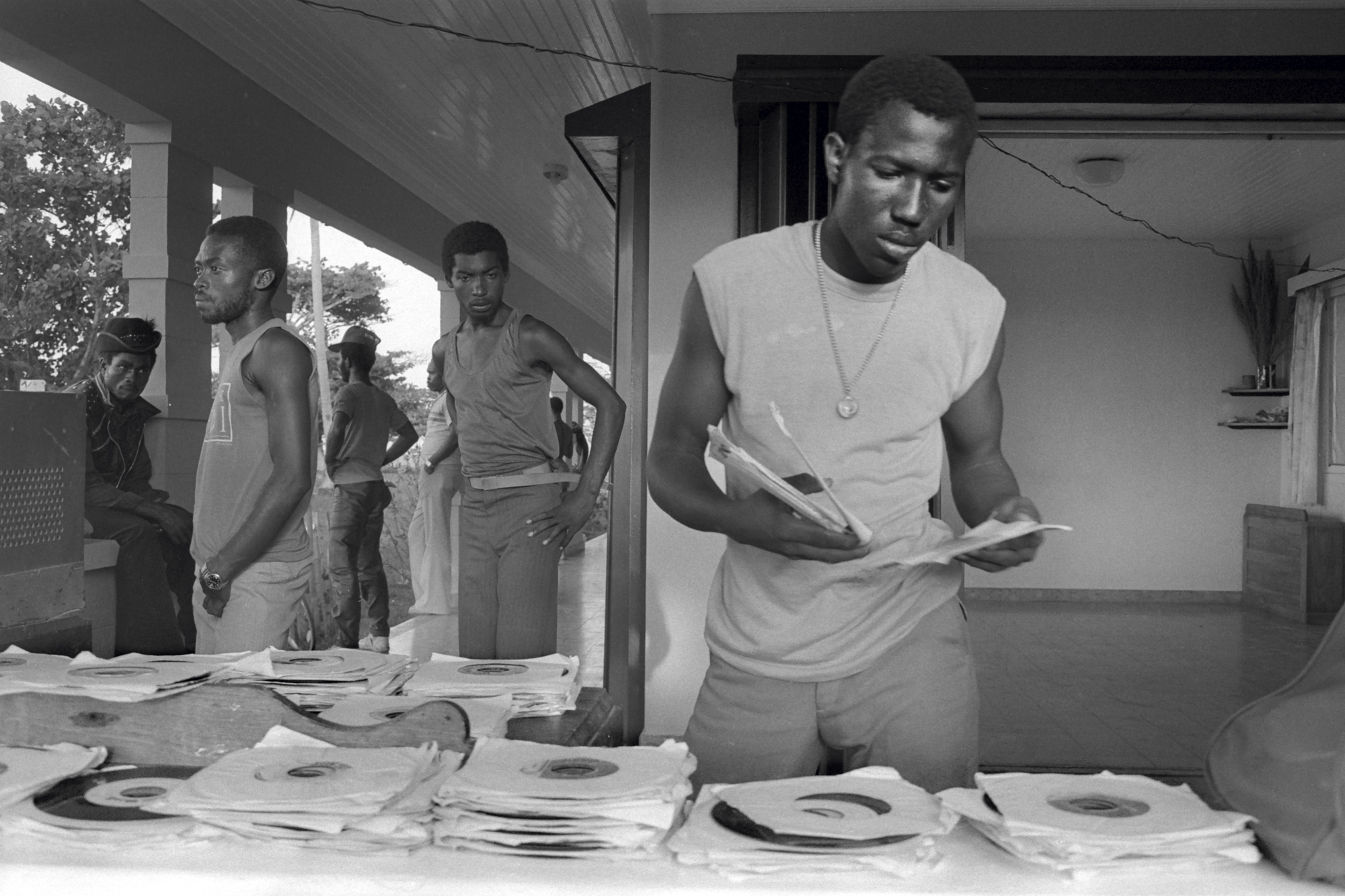

Entranced by what he had witnessed, Wayne began making regular trips to Jamaica to work on a range of social documentary projects. At the time, the vibrant dancehall scene was flourishing at 1 Robert Crescent, home to Sugar and the flourishing Youthman Promotion Sound System and organisation. Widely considered to be the godfather of dancehall, Sugar changed the game when he showed up at Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd’s legendary Studio One in 1977 with a revolutionary idea: rather than audition with a band, he sang over a rhythm in the Studio One vaults.

The two went on to create two albums together, giving Sugar an education he couldn’t find anywhere else and inspiring him to pay it forward by creating the Black Roots music collective in 1979 with artists including Little John, Tristan Palmer, and Tony Tuff.

After the success of their first album, Ghetto-ology, Sugar decamped for the UK to sing and produce lovers rock records. Although he hit the top ten hit with “Good Thing Going” in 1981, Sugar needed more than money and status to be a successful artist: he needed vibes that could only be found on the island of his birth. He returned home to resume his journey as a roots artist and producer with a vision to create YP in 1984.

Blessed with the ability to spot raw talent, Sugar envisioned YP as a “University of Dancehall” where new singers like Tenor Saw, Junior Reid, and Yami Bolo could practice alongside their elders, gaining wisdom and guidance from artists of all generations. Headquartered at 1 Robert Crescent, where Sugar was born and raised, YP became a training ground for young artists to grow when they became breakout artists on the dancehall scene.

When Wayne arrived at YP in 1986, a new crop of artists like Tony Rebel were up next, taking part in Sugar’s innovative approach to music making. Necessity being the mother of invention, Sugar freely experimented with ways to bring down the cost of studio time and record production with computerised keyboards and drum presets, which stood in striking counterpoint to the gritty lyrics that spoke to their shared realities.

Throughout his life, Sugar maintained the same integrity he held walking away from a UK music career, preferring to use his talents and skills to help new artists emerge. He took the position of facilitator rather than boss, investing the proceeds into building the studio rather than lining his pockets.

“Sugar’s house was a revelation to me,” Wayne says of that first night on the scene. After returning home, he hooked up with Sugar’s brother Earl Minott and Youth Promotion UK, photographing rehearsals at their Brixton home and travelling with them to Birmingham and Handsworth, where racial tension and police harassment ran thick. Soon thereafter, he began shooting for Black Echoes, the only Black music magazine in the UK, documenting historic events, including Aswad’s 10th anniversary in Paris and Black Uhuru at Glastonbury.

Over the next 17 years, Wayne documented the sound system culture in London and Jamaica, going on to create his celebrated “Inna Dancehall Style” project that spotlights Dancehall Queens and patrons of the scene. The photos were first published by The Guardian in 1993, the same year he moved to Jamaica, where he lived and worked for the next decade.

Now Wayne returns to his roots for a look back at where it all began in the new book, Sound System Culture Jamaica & UK 1986–88 (Café Royal Books). The book features photographs of the dancehall scene on both islands, providing an inside look at the ways in which music helped to shape and maintain bonds between the motherland and diaspora.

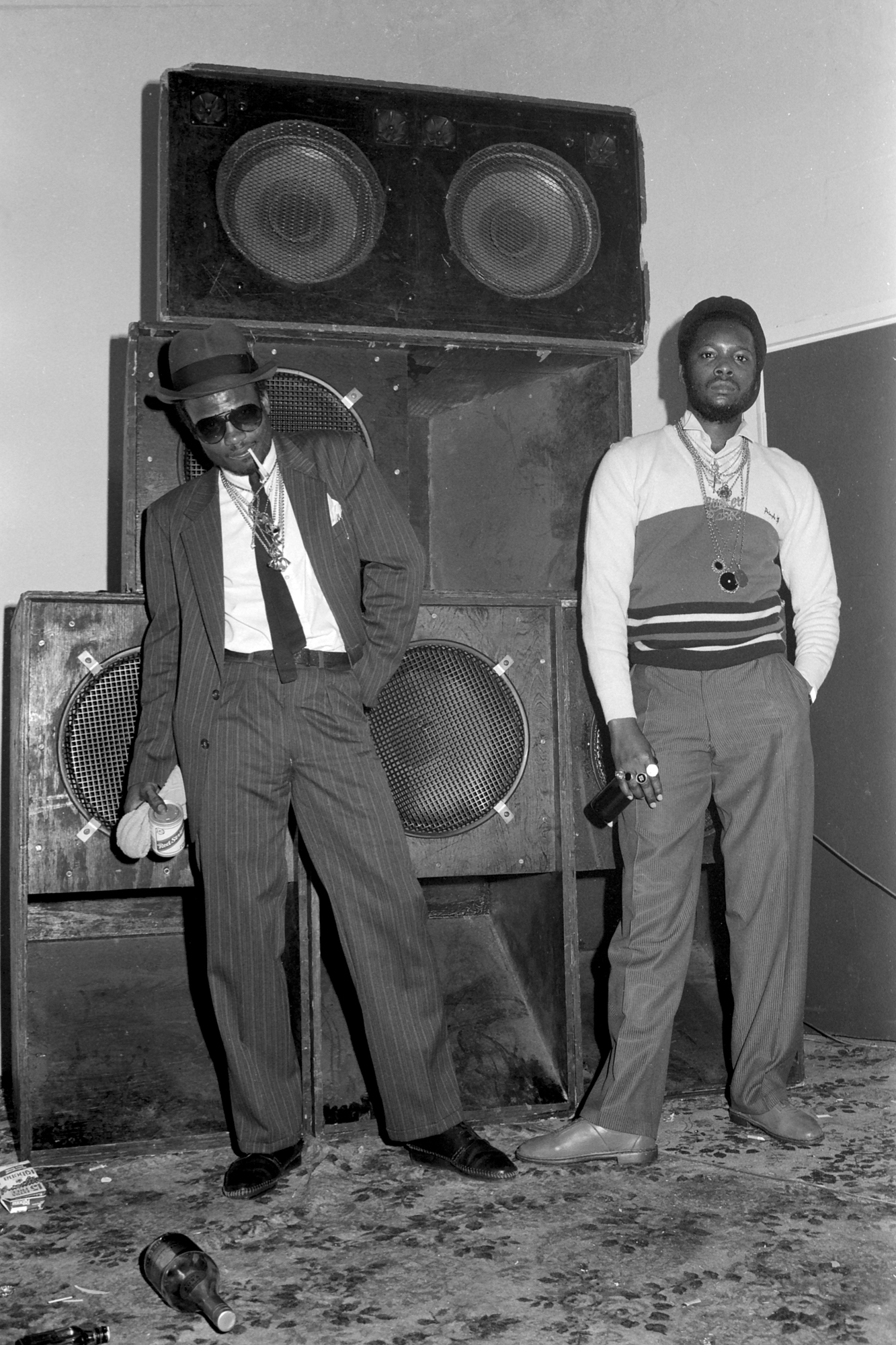

In August 1988, Wayne travelled to Central Village, a settlement outside Spanish Town, St Catherine, to photograph the Black Ruler sound system. Just 40 years earlier, the first Rastafarians established their own community, known as Pinnacle, in the mountains just above Spanish Town. By rejecting white supremacy, they were branded as a threat and targeted by the British colonial government for destruction.

Despite the fall of Pinnacle and systemic persecution, Rasta culture survived on the outskirts of Kingston, the tenets of its spiritualism and philosophy making its way into the music that came full circle with dancehall. “Black Ruler was hardcore,” Wayne says. “They didn’t play much outside of Central Village, but they were booked for a local dance down on the North Coast. I enjoyed the dance until it got a bit heavy and things broke up. The music had to be played very late, and the people from Kingston didn’t quite mix with the North Coast.”

Returning to the start of his photography career, Wayne pays homage to these groundbreaking artists with reverence and joy. Four decades later, his excitement remains palpable as he recounts photographing the underground scene whose influence continues to shape the fashion, music, and rebel culture around the world today.

Credits

Photography Wayne Tippetts