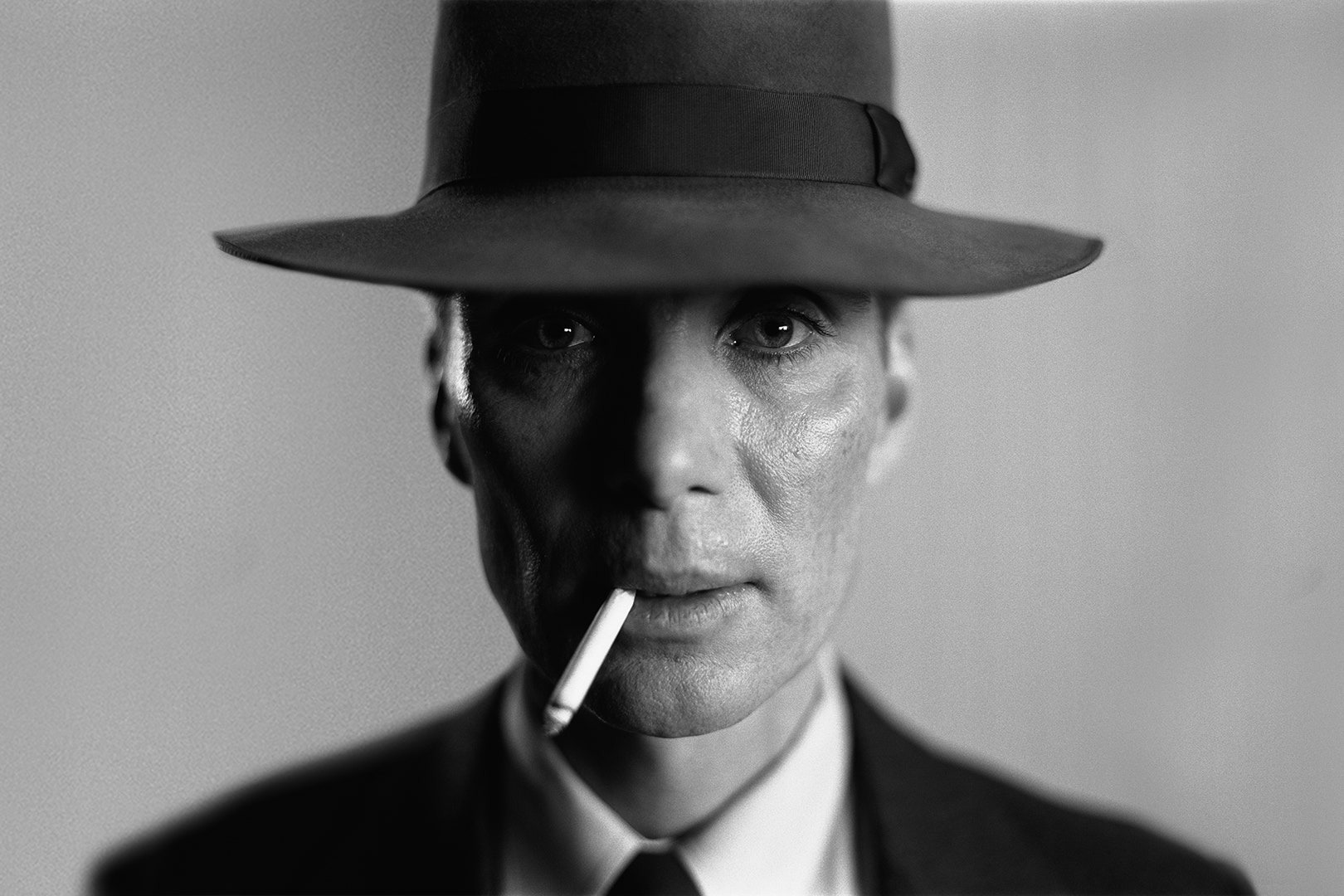

Coming to the end of Barbenheimer weekend, here are my stats. I have seen Barbie, but I have not seen Oppenheimer. This is not a feminist or aesthetic decision. It’s because Barbie is one hour and 54 minutes long, while Oppenheimer is just over three hours long.

I’m not alone in being perturbed by the length of the movie; over the weekend on TikTok and Twitter people posted the exact time that it was safe to go to the bathroom during Christopher Nolan’s epic. Others shared the app RunPee which is specifically created for this purpose (if you’re interested, it’s when Oppenheimer’s brother first comes on screen, apparently). These people are well practised at the art of knowing what parts of a cinematic epic can be missed because, lately, it seems filmmakers are well practised in the art of making movies and flat out refusing to cut them down to non-epic length.

James Cameron’s original Avatar came in at two hours 42 minutes. A decade later, Avatar: The Way of the Water, comes in at three hours and 12 minutes. The original Dune (1984) came in at two hours 17 minutes. Denis Villeneuve’s upcoming sequel to his reboot is slated to be three hours and 15 minutes. Even non-cinematic releases have embraced epic length; Netflix’s Blonde, released last year, was two hours and 46 minutes long, which felt reasonable given that three years before The Irishman ran for three hours 29 minutes. Ari Aster’s breakout horror, Hereditary, was a reasonable two hours and seven minutes. His follow up a year later, Midsommar, came in at two hours 28 minutes. Beau Is Afraid, released earlier this year, was two hours 59 minutes. Then there is Zac Snyder’s extended cut of Justice League that comes in at a criminally long four hours and two minutes.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

Back in 2019 when Martin Scorsese released The Irishman, a long run-time was seen as a problem rather than what it is now; a thing to be endured or a badge of honour. “Meanwhile, traditional Hollywood studios beholden to box office sales have become progressively risk-averse in recent years (producing a three and a half hours-long film definitely counts as a risk, no matter how esteemed Scorsese is),” one article reported at the time. “A fact the filmmaker recently lamented when he argued that ‘cinema is gone.’ Perhaps The Irishman will help bring it back, if audiences can gear up for the long haul.”

It seems that the long movie is now a badge of honour for directors, screeners and filmmakers. Longer is more theatrical, more expensive, more intrinsically artistic. Compare this to previous cult movies that a generation before were noted both for their impact and for their short runtime; La Haine is only one hour 38 minutes long, Gummo is only 89 minutes long, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Pink Flamingos, Kids, Trainspotting — all really very short! But nowadays the ‘kill your darlings’ editing method has been inverted. “Most long films could be promoted as special and prestigious,” Dana Polan, a cinema studies professor at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, told Variety. “There was an assumption that length equaled quality. It’s almost to say, we’ve spent the money — let’s flaunt it.”

I had a theory that, given these lengthy blockbuster examples, the 90 minute movie was simply gone, done, over. But then I looked back at the past year’s releases and was proved sadly wrong. Rye Lane was one hour and 22 minutes long. Aftersun also ran at just over 90 minutes. As did Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret, and Sydney Sweeney’s Reality. Even Infinity Pool and A24’s The Whale were both under two hours long. Clearly 90 minute films still are around, but why does it feel like films are getting longer then. Why do we spend so much time talking about the long ones?

TikTok will edit these movies alongside clips from Subway Surfer or Temple Run or pushing vodka bottles down flights of stairs to see if they break. We don’t ever have to concentrate long enough to take anything in. We can always be distracted.

“These days, there’s a lot of talk about long running times,” Sarah Atkinson, professor of screen media at King’s College London, told The Guardian last year following the release of Tenet (which somehow didn’t even reach three hours). It’s all part of incentivising people to go out and pay for a ticket, which they won’t do unless it’s for something special – a big, epic film. Just look at the Marvel franchise: almost every one is well over two hours.” Film length isn’t going up, she concluded, but we think it is. Why? Sarah believed it was simply down to good, savvy marketing.

One other answer could be that our attention span is just worse now. That our attention span is destroyed, actually, by short form social media video and constantly having access to information chopped up to be digested as quickly as possible. We watch TV at double speed or 1.5 speed with the subtitles on. We can look up the plot on Wikipedia and even if we can’t be bothered to go to the cinema and figure out when it’s safe to pee, in six months or a year’s time we can watch whatever film we missed on TikTok anyway, chopped up into parts in a post-123 Movies age of piracy. Even if this doesn’t captivate us enough, someone will have edited those cut-up clips further, and put them above or alongside clips from Subway Surfer or Temple Run or people making cakes or pushing vodka bottles down flights of stairs to see if they break. We don’t ever have to concentrate long enough to take anything in. We can always be distracted.

It’s true also that longer movies always did exist, especially for vast historical epics like Oppenheimer. Lawrence of Arabia, released in 1962, ran at three hours and 42 minutes originally (it was cut down by both 20 and 35 minutes in later releases before being extended to three hours 48 minutes in 1980). Further back, 1939’s Gone with the Wind was three hours and 44 minutes long. Cleopatra, one of the world’s longest cinematic commercial films ever, was released in 1963 and is three hours and 53 minutes long. But a generation later, longer films made headlines when they tried to embrace the epic-runtime set by their predecessors. James Cameron’s Titanic – three hours 14 minutes – was originally released for home media in a two VHS bundle to account for its length. All of the Harry Potter movies were just under or over three hours long; Chris Columbus and later directors knew that the franchise’s rabid fan-base would watch, no matter the length, and so studios would pay for big, lengthy productions too. Even accounting for the amount of lore creators had to include, the length is frequently cited as one of the flaws of the series, which is now being remade into more easily digestible TV sized chunks.

For Oppenheimer though – Christopher Nolan’s longest movie to date – the length doesn’t seem to be off-putting, even with the fact the movie’s 70mm film reels are clocking in at over 600lbs (I did actually try to see it, but every cinema close enough to make is sold out even today). Perhaps we’re just more used to a modern lengthy epic than we used to be. It made just over $80 million in opening weekend takings, making it the director’s biggest non-Batman box office hit to date. Barbie, for transparency’s sake, did take $150 million in the same weekend. Despite its three hour length people still embraced Barbenheimer weekend, going to one movie and then the other, spending an entire day at the cinema, unfatigued and impressed. Maybe Barbenheimer weekend is not just what we needed to reinvigorate movie theatres, but what we needed to fix our broken attention spans. We have become death, destroyer of short films.