This piece was originally published in January 2017. With a new show opening at the Tate Modern this week, we’re republishing it.

She was part of a generation of artists who emerged in the UK during the end of the Empire…

Lubaina Himid was born in Zanzibar in the 50s, and came to the UK in the 60s after the colony off the east coast of Africa gained independence. It’s a story shared by many who emerged in the art world at the same time as Lubaina in the 80s, exploring the same issues of post-colonialism and racism.

John Akomfrah was born in Ghana before moving to the UK as a child; Mona Hatoum, who was born in Lebanon, before relocating to London and being forced to stay when the country descended into civil war; Keith Piper was born in Malta to an Afro-Caribbean family, before they relocated to Birmingham; Rasheed Araeen grew up in Karachi and moved to London after graduating, where he began working in sculpture.

The British Nationality Act of 1948 gave the right to live and work in Britain to almost all the subjects of the old Empire. By 1961 over 100,000 people were arriving a year from around the commonwealth, drastically changing the racial and cultural landscape of the country.

This generation of emigres, immigrants and refugees would form a vital part of Britain’s multi-cultural post-war story; leaving an indelible mark upon our island. How much of our culture do we owe to them? Everything from the music we listen, to the food we eat, has been shaped and morphed and formed by them. Art, of course, is no different…

It was from this that the Black British Art Movement emerged…

This generation discovered, first hand, that England wasn’t a promised land. The 60s saw the rise of Enoch Powell, the 70s the National Front, the 80s consolidated it all together under Thatcher.

The racist attitudes on the streets were mirrored in widespread institutional racism, specifically in the police force. It was out of this that they emerged as a movement, an artistic response to the world around them, they sought to fight back.

Lubiana was at the forefront of it.

They were most vital art movement of the 80s…

Before the YBAs, there was the BBAs. The Black British Artists of the 80s don’t really have a lot in common in the Young British Artists of the 90s, but it’s often clumsily and lazily supposed that the YBAs built the art industry in this country, specifically London, revolutionised everything, blah blah blah.

But they dispute that, and the BBAs (I know, I know) were everything the YBAs weren’t; politically active, politically sincere, politically engaged, political full stop. If the YBAs were all about commercial opportunities in the capital, drinking lager and being lads, the BBAs were more about engaging with institutions and working in the old, unfashionable industrial heartlands of the country. Their work was often less materialistic, less showy, less obvious, always intellectual.

The point of the comparison is that you should probably rethink how you think about art movements in this country.

And were rebels out of necessity…

Rather than rebels as a pose. The art world, its gatekeepers and its institutions at the time were predominantly white (even more predominantly white than now, which basically means totally white) and they had to fight to have their voices heard and ideas recognised.

It probably didn’t help they were all working class, as well as black, and mostly from such unfashionable cultural hotspots as Preston, Birmingham, and Wolverhampton. But in a time of division, they formed a necessary bloc taking the fight not just to the art world, but to the real world too. This was a movement of great intellectual weight and political importance, but the group were fighting not just on canvas and in the gallery, or in the rarefied halls of institutions, but on TV.

The recently launched Channel 4 broadcast many of the movements AV works, particularly by John Akomfrah’s Black Audio Film Collective, straight into the nation’s homes.

Lubiana pioneered a new way of painting history and a new narrative of blackness…

The movement was given theoretical form by the likes of Stuart Hall, and drew influence from Pan-Africanism and post-colonial theorists like Frantz Fannon and Edward Said. Rasheed Araeen was part of the Black Panthers for a time, and a bit older than the rest, organised major exhibitions of their works at the Hayward. But Lubiana – alongside Keith Piper’s BLK ART GROUP and the aforementioned Black Audio Film Collective – was the leading organiser in the movement, curating many exhibitions and supporting many artists, and without her tireless work, many would be worse off. The mixture of emotional intensity, intellectual density and pure beauty in Lubiana’s work, stands as the centrepoint of it all.

One of the major concerns of the Black British Art Movement was placing the history of British art in the context of their race, and one way of challenging the racist present was by exploring the racist past. In the 80s, when she was working in London, Lubiana’s practice involved delicately arranged but totally overwhelming assemblages of narrative fragments, rooted partly in her study of set design at university. This narrative she was building was a challenge to dominant old, white, ways of thinking about art and history.

Her work uses drama and theatre to investigate race and politics…

One of her most famous is A Fashionable Marriage, from 1986, which reconfigured white history painting by putting blackness centre stage. Based around William Hogarth Marriage A La Mode, from the 1740s. Across six paintings and in his typically satirical style Hogarth dissects the mores and morals (and lack of) of the upper classes seen through the narrative of an arranged marriage. Lubiana’s A Fashionable Marriage, reimagines Hogarth’s narrative through the racial and global politics of the 80s, particularly Reagan and Thacher. “It presents a very particular way of talking about the history of why black people are here,” she said succinctly of the series, in an interview with The Art Newspaper recently.”And also about the circumstances in which we found ourselves in the 1980s.”

Or take one of Lubiana’s more recent works, 2004’s series Naming the Money. 100 cut out paintings of various black figures, each named, each with a history, imagined at a slave gathering, with the viewer free to wander through the forest of people and hear their stories, and connect with their pasts. As she’s matured her work has become broader, more open, painting with history in bigger and more sweeping brush strokes. There is something more reserved, quieter, more self-assured in the recent work, although of course the political anger and outrage hasn’t died down.

She’s finally getting the recognition she deserves…

Alongside the other members of the black art movement in the 80s. For much of the 90s and 00s they were not as present as they should’ve been, obliterated by the sturm and drang of Damien Hirst etc. But their legacy continues to grow and grow, and they’re having something of a second wind right now. The issues they discussed and dissected are more relevant than ever. There’s an easy parallel between Trump and May and Reagan and Thatcher, but the Black Lives Matter movement has spilled out off the streets and become part of cultural conversation too.

John Akomfrah took to the Venice Biennale two years ago to present a major new work; Nottingham Contemporary is staging a retrospective of the era later in the year too, and the movement formed a major part of a great exhibition in Eindhoven last year that looked into the political art of the 80s. The death of Stuart Hall put his legacy in new light, for a new generation. You can see politically-engaged methods of art making and institutional critique everywhere right now. And, of course, Lubiana is the subject of two retrospectives in two cities, opening on Friday as well.

Lubaina Himid at the Tate Modern runs 25 November 2021 – 3 July 2022

Credits

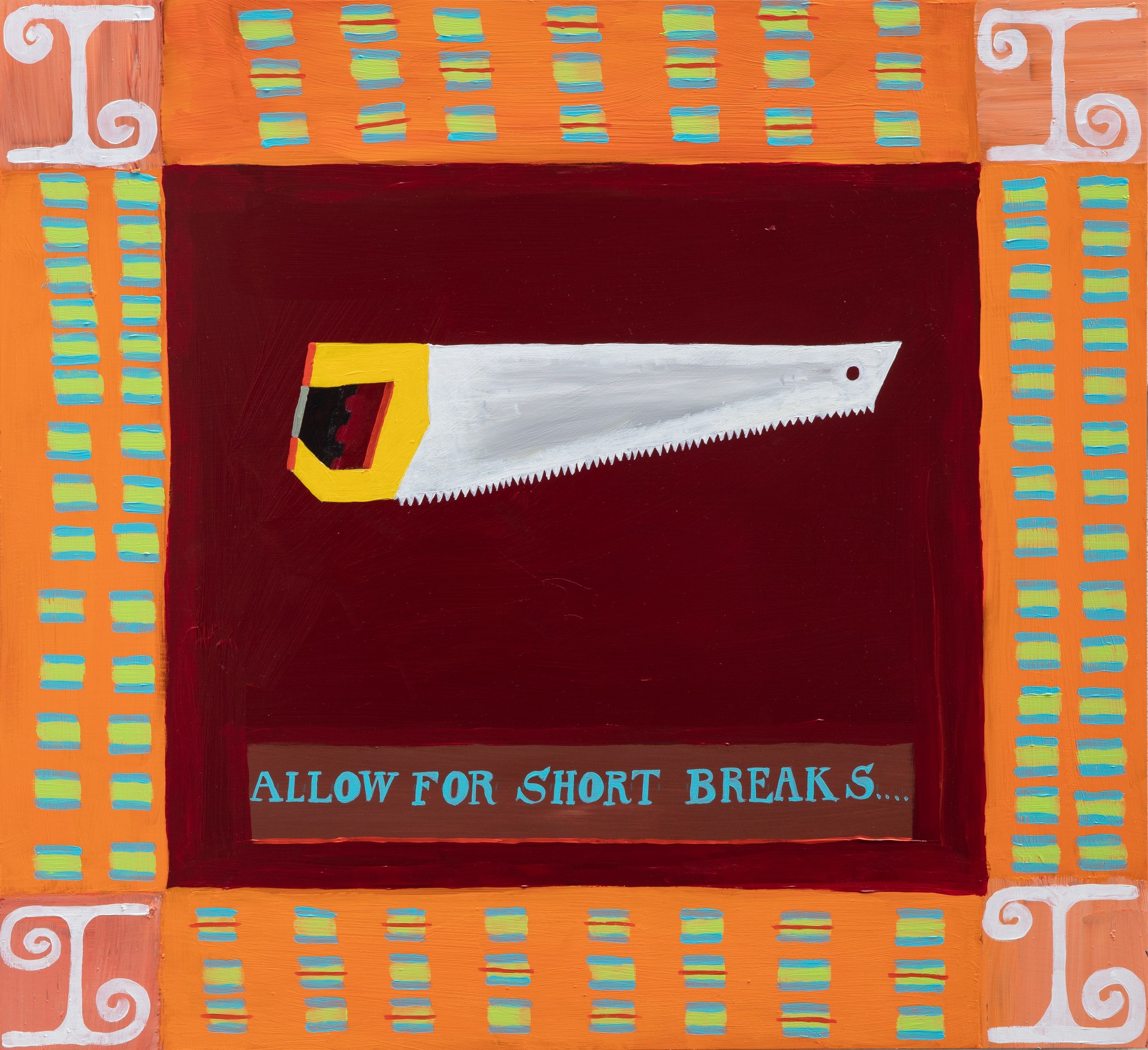

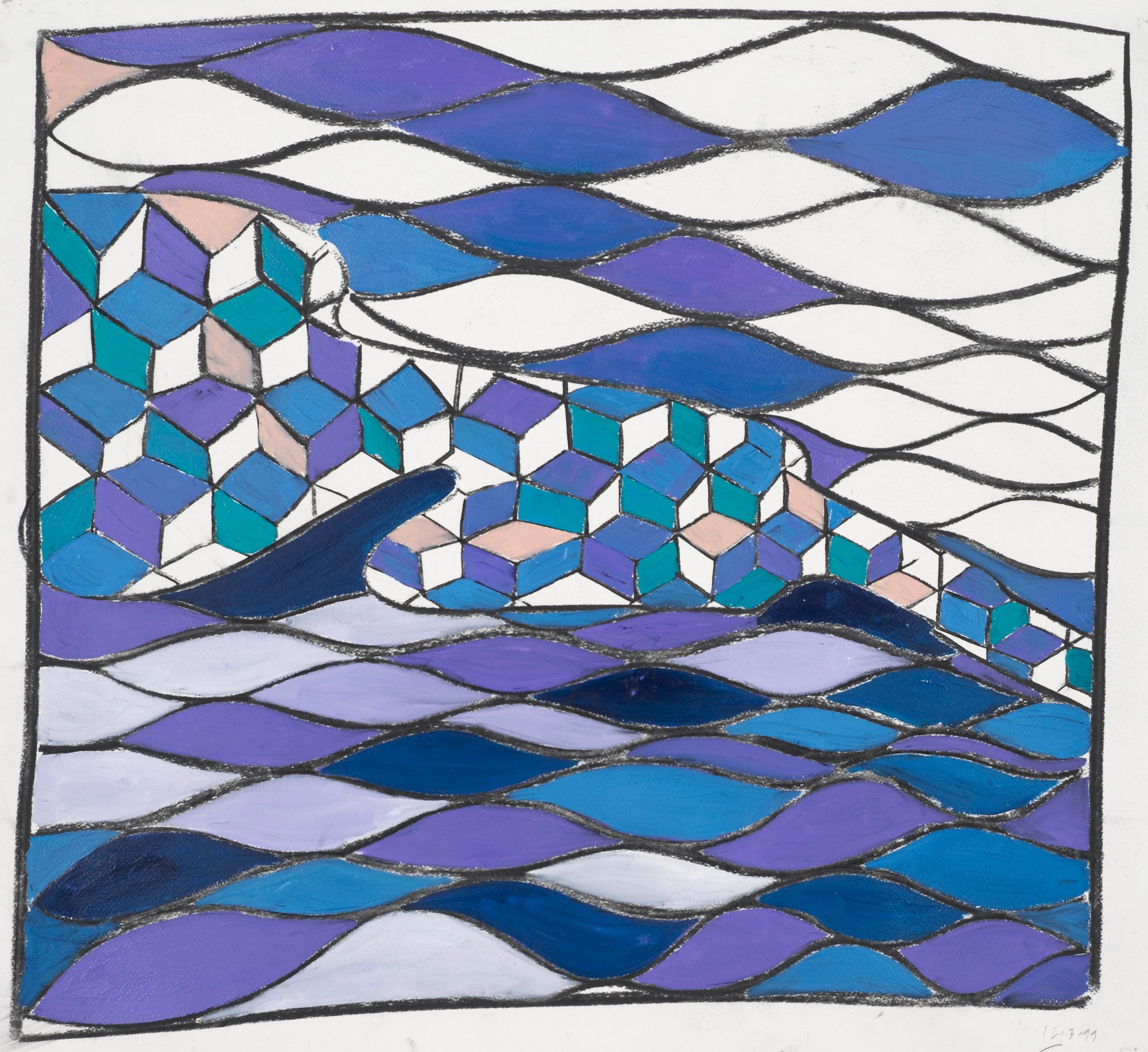

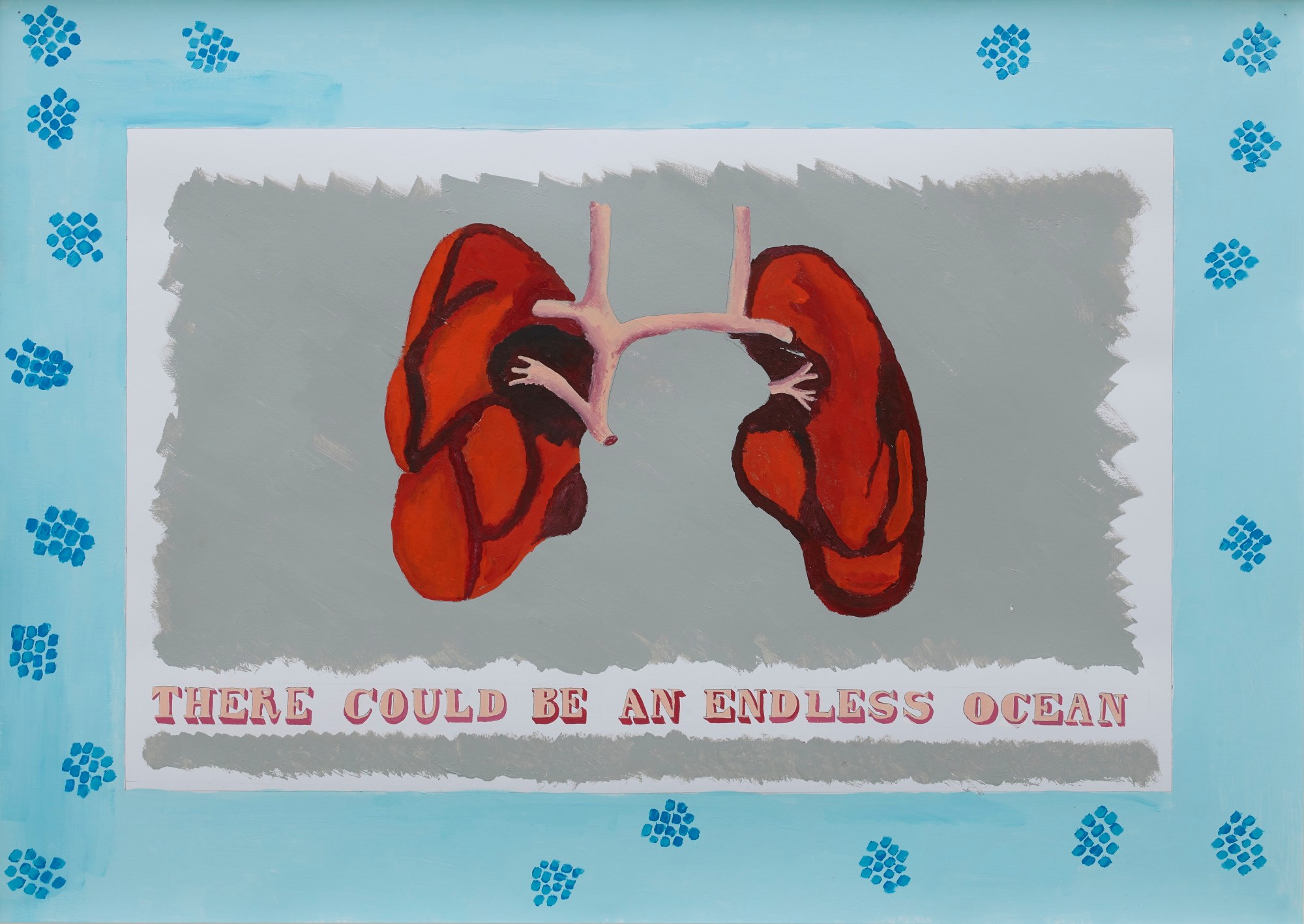

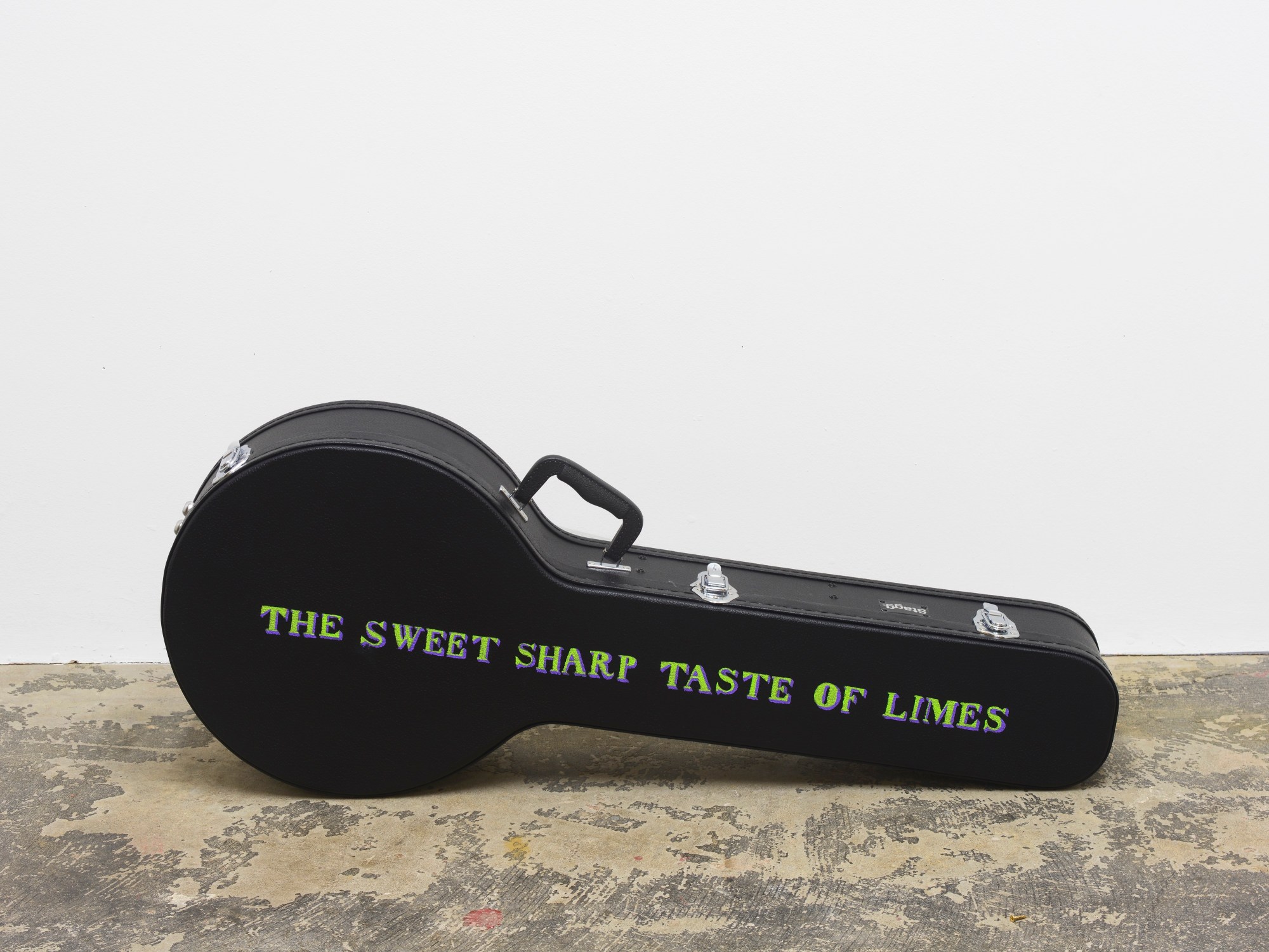

All images © Lubaina Himid