This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Post Truth Truth Issue, no. 357, Autumn 2019. Order your copy here.

There’s a confusing air of nostalgia in Britain right now, a rose-tinted delusion of what made Britannia so Great anyway. For the many who voted to leave the European Union, especially in rural towns where British production (and as a result, jobs) has continually dwindled, it’s about looking back in anger and re-claiming something, a time that was supposedly better way back then. It tends to be the older generation who miss the days when three-foot-to-a-yard Britain (England, really) belonged to them. You’ll hear them saying they want their Britain back. A time when they felt comforted by white faces at the village fair, drank Tetley tea instead of oat-milk lattes, double-spaced after full stops, laughed at the slapstick silliness of Carry On films, and the morning paper came with a side of tits on Page 3.

You get the picture. The main point is that isn’t modern Britain, or even a modern reality. It’s certainly not such a warm, fuzzy view for those marginalised and oppressed by deferential old Blighty. So it’s a strange time to consider nostalgia, particularly as citizens, mainly because it feels like an odd time to be patriotic. Union Jacks have never looked so regressive and aggressive. All those traditional British sartorialisms beloved by the rest of the world – waxed field-jackets and trench coats, Savile Row suits and Carnaby Street mods – suddenly look a little myopic. And, at a time where so many of us feel ashamed of our country, these badges of patriotism feel like the antithesis of multicultural Britain.

Sarah Burton reframed that narrative with her most recent show as creative director of Alexander McQueen. Set in a dilapidated Parisian warehouse, which had been transformed into a rural British factory, it was an interesting ode to Britain. It could well have made people feel uncomfortable, but it didn’t because, beyond all that noise – in a time of a divided Britain whose future is being gambled on by archaic, old-hat politicians – she put forward a very personal idea of home. Her collection was about British craft and fabrics but it wasn’t nostalgic for something that didn’t exist, or patriotic for the sake of pride in the past. Instead, it wove a tapestry of deeply personal stories and an illustration of how craft can be imbued with emotion and optimism. Like Lee McQueen before her, it told a story of how the past was then while borrowing pieces from it to create a more progressive image of tomorrow.

Sarah begins each collection by talking her close-knit team on a field trip – to visualise with their own eyes, instead of copying-and-pasting images onto a moodboard. She grew up in a Macclesfield set in the rural shadow of the Peak District, surrounded by factories and mills that make traditional British textiles, and this season she went back there with her team. “We all live in cities so it’s about escapism,” she said. “It’s about how we are grounded in this reality, and I looked at nature as an armour for now. A sense of reality and authenticity.”

Authenticity is an overused word but, in her case, it couldn’t be more apt. You won’t find Sarah on Instagram or on the red carpet or at parties. She hardly gives interviews and is one of a handful of women who have held a top job at a major fashion house for almost a decade, with no signs of faltering. At her core is a love of making things, and she permeates every single thing she makes with meaning.

So what she and her team stumbled across, both outdoors in rambling fields and inside the hubbubs of production, became the starting point for the collection. A coffee pot filled with heddles, which Sarah stumbled across, became the impetus for a column gown spangled in laser-cut sequins to evoke its construction. As it slinked by on the catwalk, it had the rhythmic patter of a loom shuddering into action. The team made discoveries of local suffragettes – and their green and violet sashes were reimagined as drapes of chains and studded leather. Old photos of punks in village halls in their leather jackets were spliced with images of rose queens; the girls in silk dresses who lead springtime processions with flowers in the hair. Look closer at the bodices of the evening gowns and you noticed tufted embroidery redolent of birds historically symbolic of the North: a Leeds owl, the Blackpool seagull, the cormorant of Liverpool.

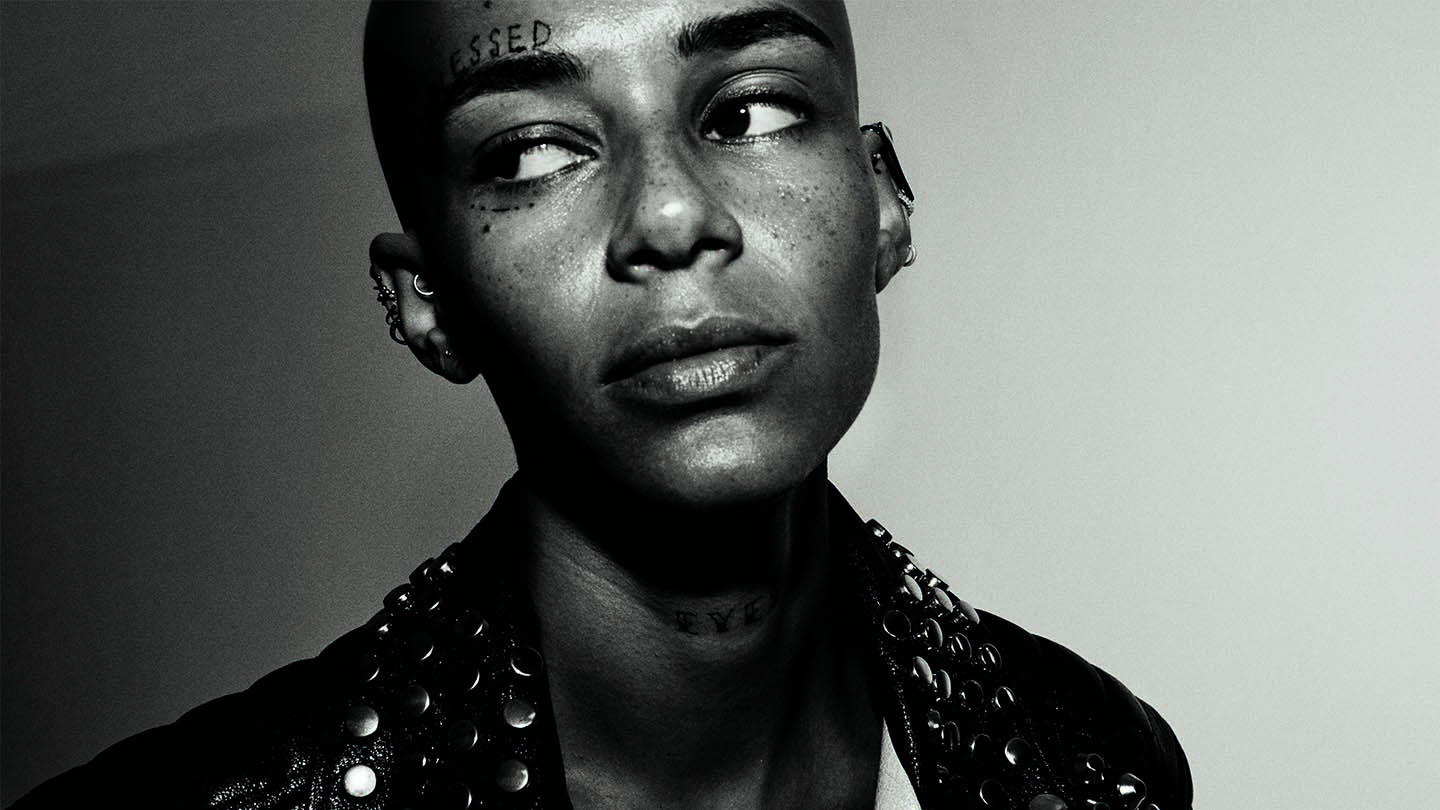

At a time of divisiveness, this was a simple expression of unity – the idea that clothes can offer a sense of protection and craft can create a sense of community. The banal became beautiful, the mundane became spectacularly interesting. On a diverse range of models – in ethnicity, size and age – there stood a distinctly modern image of British heritage, a contemporary reworking of the English Rose. “Armour” was the word Sarah kept mentioning. Her belief in strength and sensitivity, of someone’s right to be feminine and masculine and anything in between – discarded hackneyed clichés of androgyny – is imbued in everything she does, like Lee McQueen before her.

Central to that philosophy is sharply sculpted tailoring, which came with whorling magenta satin roses as sleeves or a dramatic Victorian bustle. “Because I come from the north, and tailoring is inherent in everything McQueen does, it’s all about tailoring for me,” she explained. Of course, Lee McQueen cut his teeth on Savile Row, where he apprenticed and learned how to cut a jacket with razor precision. When a 21-year-old Sarah Burton joined his side in 1996, while on her placement year at Central Saint Martins, everything was still very much made in the Hoxton studio by the handful of people working on the then-fledgling label. That hands-on approach still defines the process at what is now a global brand. “A jacket, a suit – it’s the backbone of what we wear; it’s always a piece of tailoring,” she continued. “I wanted to do it without layering it or embellishing it, to do without taking away the beauty of it.”

The sculpted taffeta dresses, which she describes as “explosions of roses”, were somehow entirely crafted from single sheaths of fabric – despite their Elizabethan proportions and intricate swirling. They were a reference to the War of the Roses – set in another time when Britain was at war with itself – and the White Rose of York and Red Rose of Lancaster. Times may have changed, but the sentiment remains the same.

Fashion has a strange predilection for seeking solace in beauty, distracting itself from the doldrums with pretty, shiny things. It may seem strange, naïve even, to think that romanticism can be an antidote to the maddening world in which anti-choice legislation is being passed, children are being kept in cages and Trump is still in power. Yet, somehow, such a heartfelt expression of beauty, rooted in something so personal, is an affirmation of fashion’s ability to transport. Burton’s emphasis on British craft is less of an arrogant showcase of what was then, but a very intimate presentation of just how mighty the touch of the human hand can be right now. It’s a reminder that the most important things aren’t lost — they just have to evolve with the times.

Credits

Photography Daniel Jackson.

Styling Carlos Nazario.

Hair Mustafa Yanaz at Art+Commerce for Matrix.

Make-up Kanako Takase at Streeters using Addiction.

Nail technician Honey Exposure NY using CHANEL Beauty.

Set design Gerard Santos at Walter Schupfer Management.

Photography assistance Jeffrey Pearson, Tyler Kufs and Nate Margolis.

Styling assistance Raymond Gee, Samantha Marinos and Niambi Moore.

Tailor Thao Huynh.

Hair assistance Nastya Millyaeva and Beth Shanefelter.

Make-up assistance Kuma.

Set design assistance Beau Bourgeois and Johny Sackzo.

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.

Models Binx Walton and Anok Yai at Next.