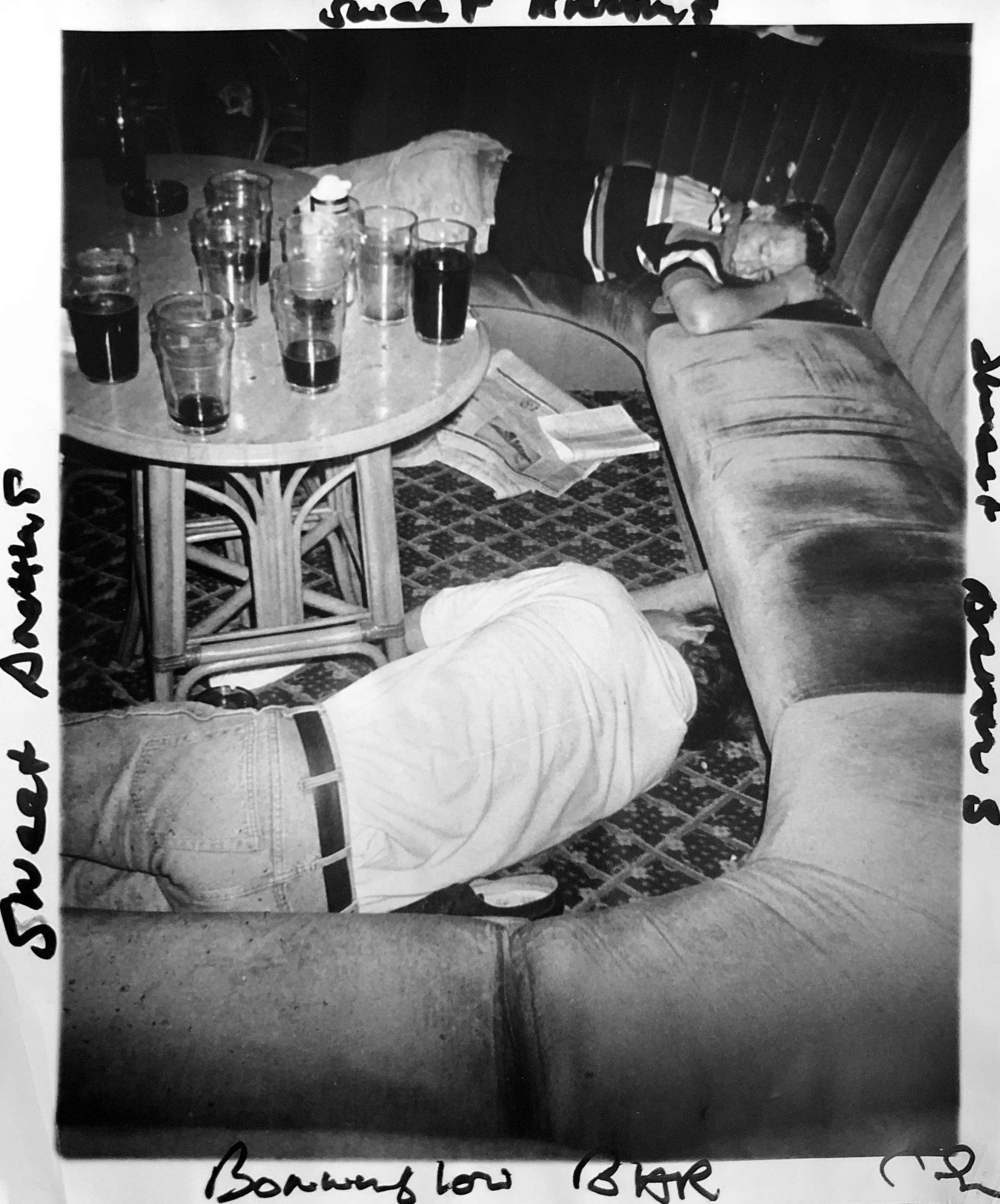

The graveyard shift is a special kind of torture, as Chris Shaw knows all too well. “I was working in photography shops across London but kept getting sacked every time I asked for a contract of employment”, Chris says. Finding himself homeless in 1992 after yet another eviction (Margaret Thatcher’s 1988 Housing Act gave landlords the green light to kick their tenants to the curb without cause), Chris spotted a vacancy in a job centre for a night porter with staff accommodation included. “I went to the Bonnington Hotel on Southampton Row. At the interview, they told me the police had arrived in the middle of the night and deported an Algerian night porter. They asked me to work that night, and it was one week later that I moved into their premises.”

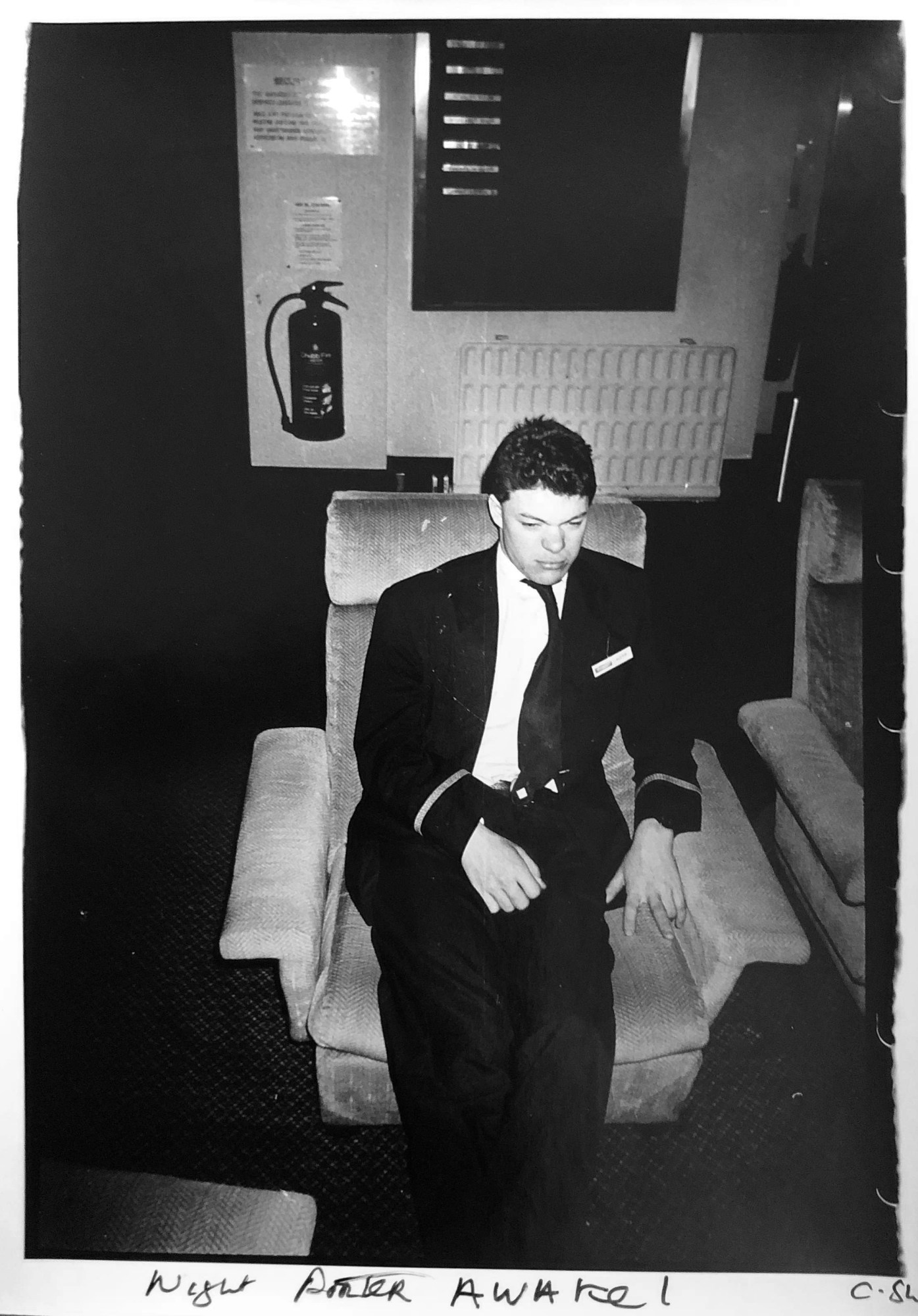

So began Chris’ decade-long stint as a night porter in London hotels. Adjusting to a new, inverted biorhythm, he turned to his low-budget compacts primarily to stay awake. But Chris — who had studied photography in the 1980s alongside Martin Parr and Paul Graham — was also unflinching in his own photographic vision. “I knew two things: it had to be black-and-white, and it had to be vertical. It was commercial suicide and contrary to the prevailing fashion. ‘Haven’t you got anything in colour?’ they’d ask, but I had lost my art school artifice anyhow.”

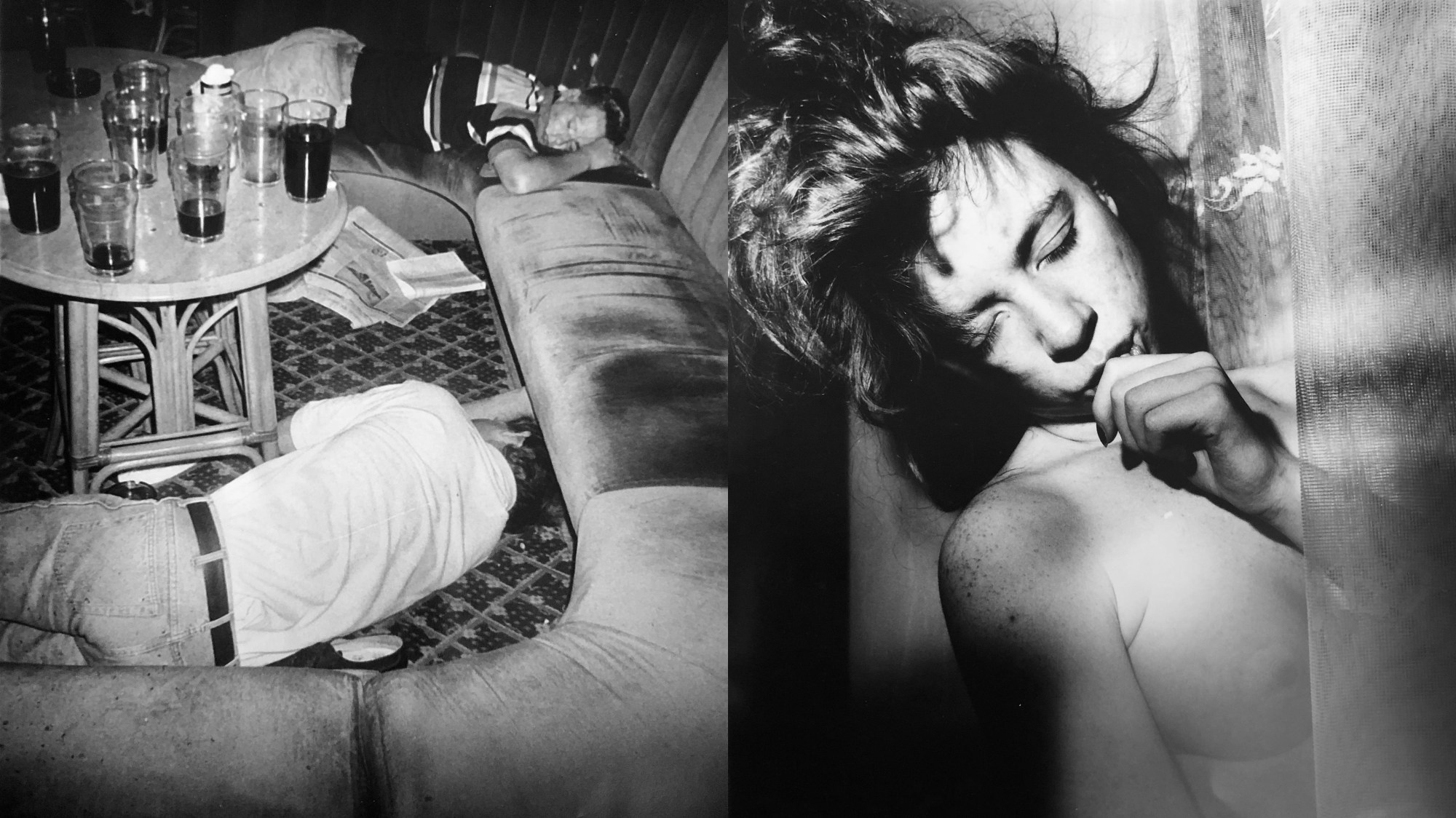

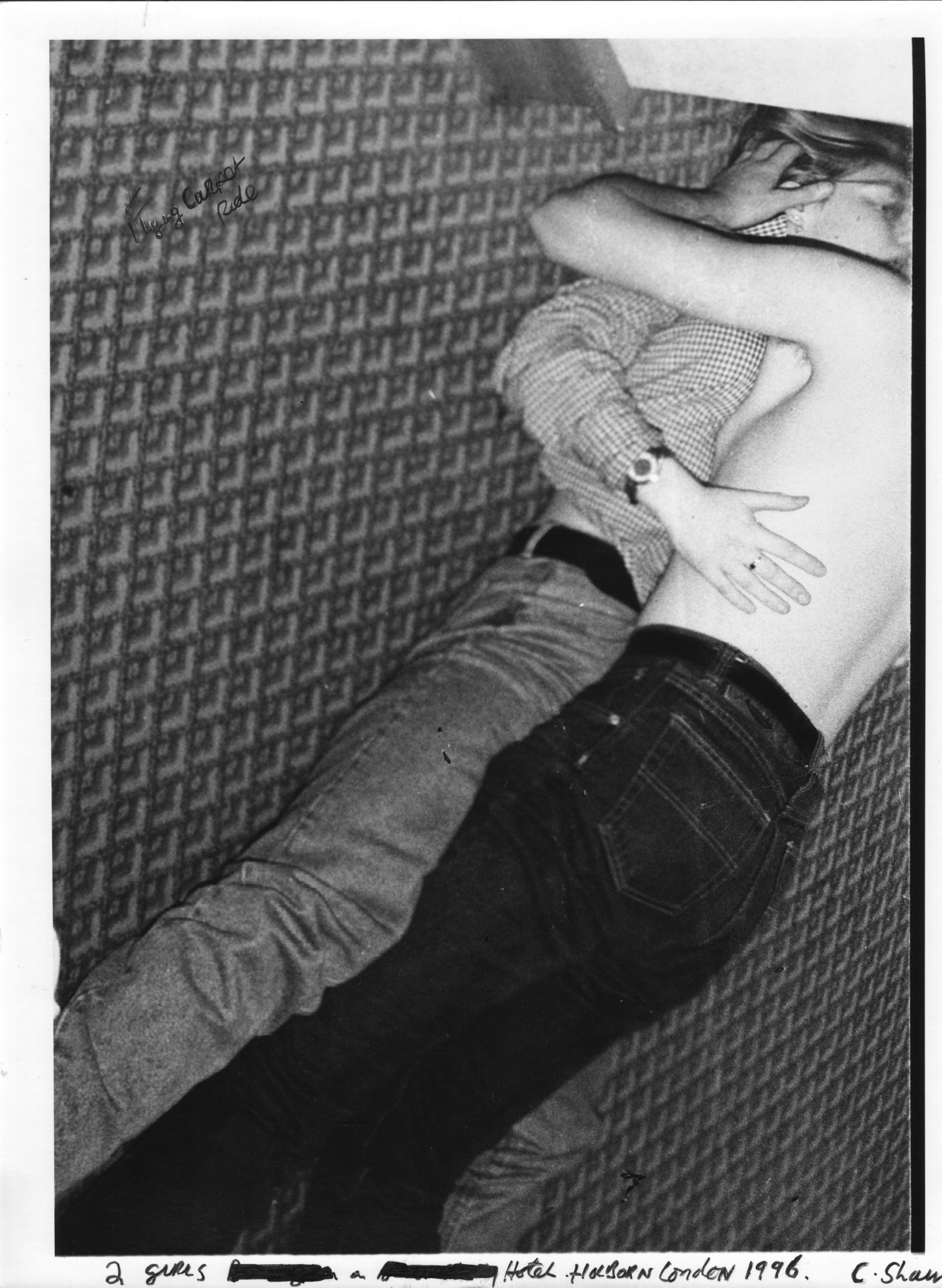

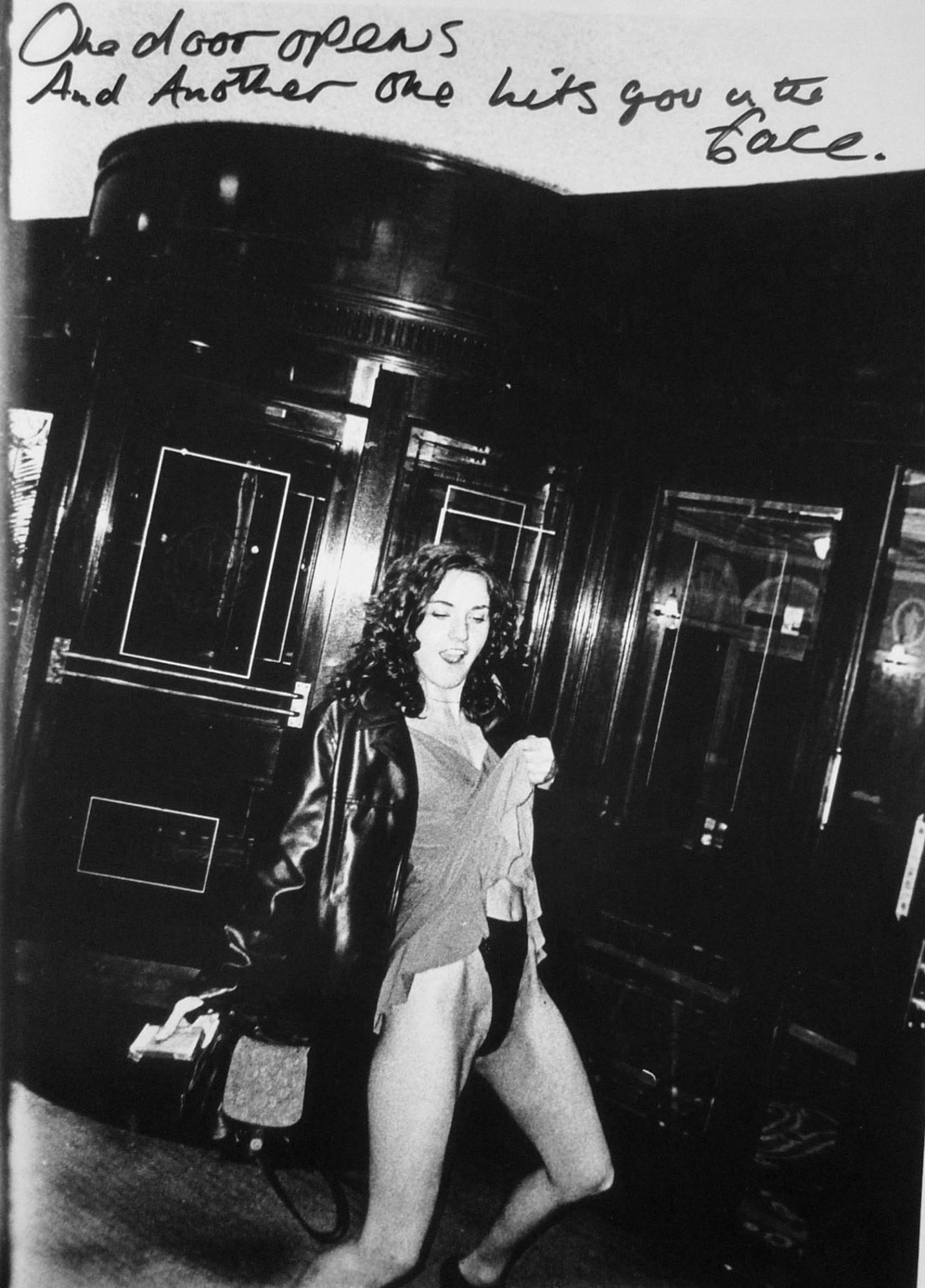

Chris is brimming with stories about his messy, hilarious and frequently wild encounters with guests. He was at their beck and call, a steadfast witness to it all: the celebrities throwing temper tantrums in the lobbies; the horny singletons trying it on for the first time in the hallways; the inebriated boozers passed out in puddles of vomit. “My least favourite tasks were walking those naked, locked-out guests back to their rooms,” Chris says. “I thought, if any one of those bastards comes down tonight, I’m going to take their picture.”

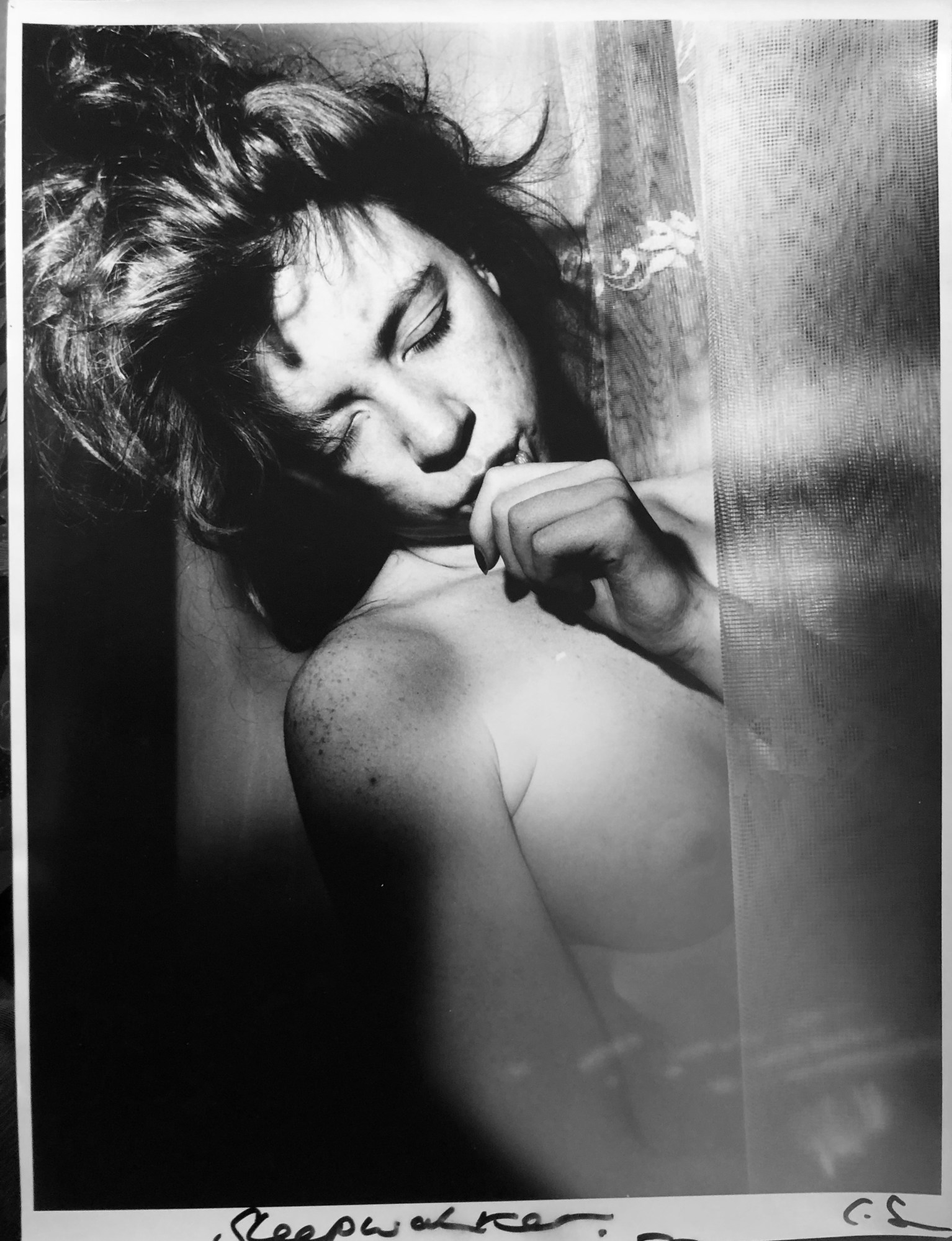

But, really, the glaring light Chris levelled at his subjects was not an indication of an insomniac’s merciless vision, but a desire to connect. Alongside the guests, Chris photographed, with astonishing tenderness, a heavy-eyed fellowship of clerks, chefs, doormen, sex workers and porters: all those crepuscular souls he found lurching through his world of vice and artificial light. Their stories — those of the poor, the evicted, the disenfranchised — mirrored his own. Chris was working under the belief that loneliness could be shared.

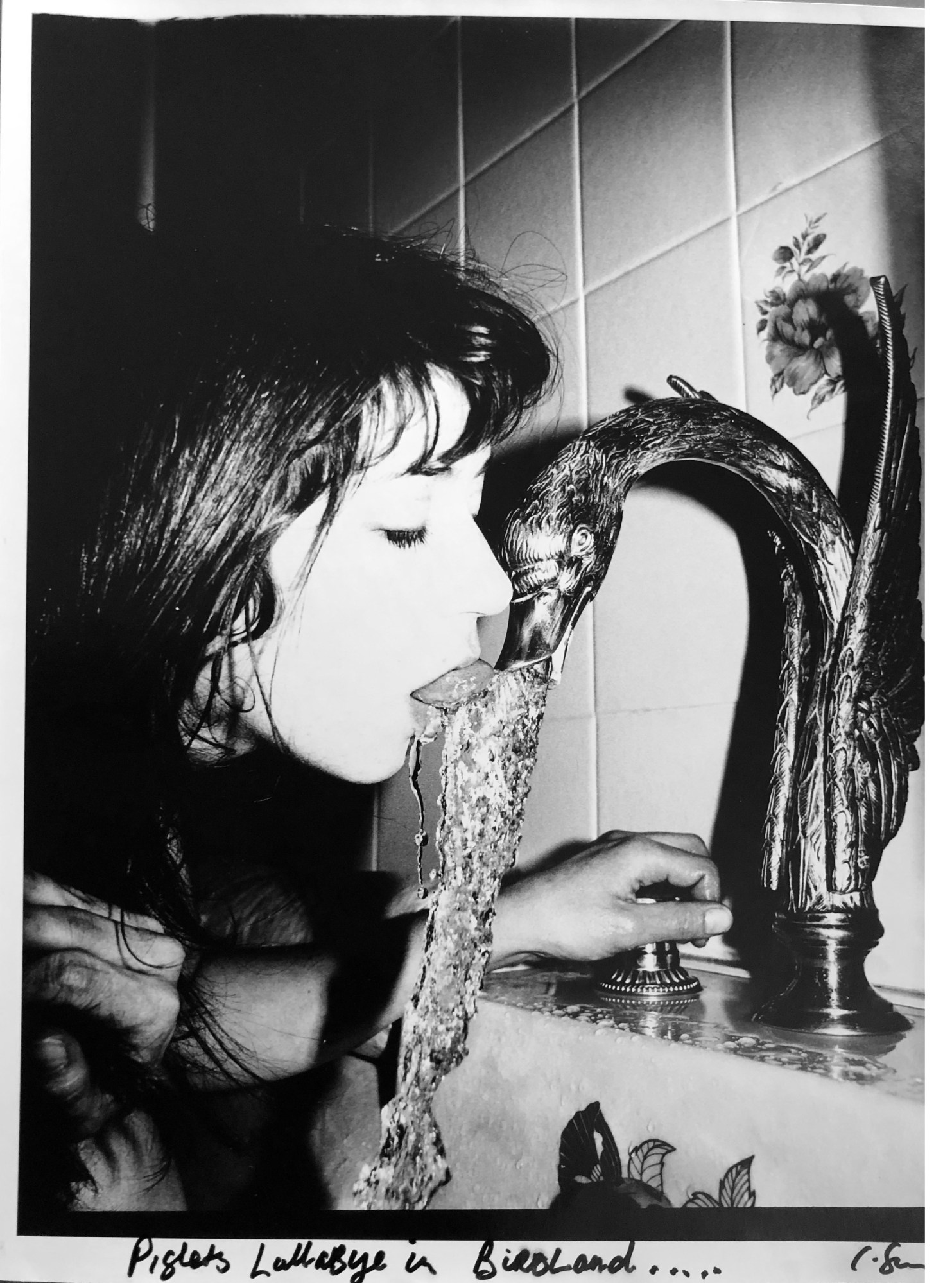

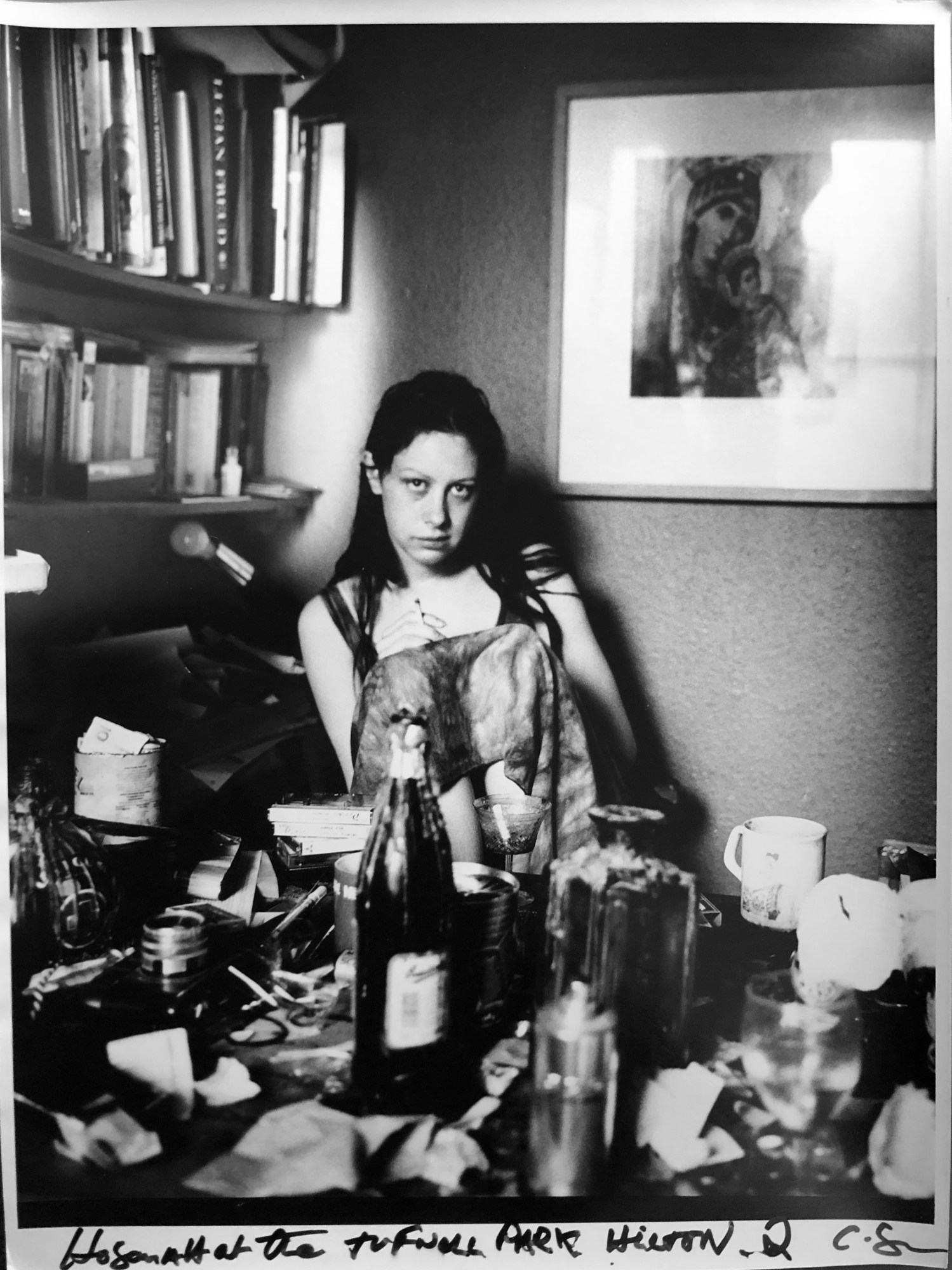

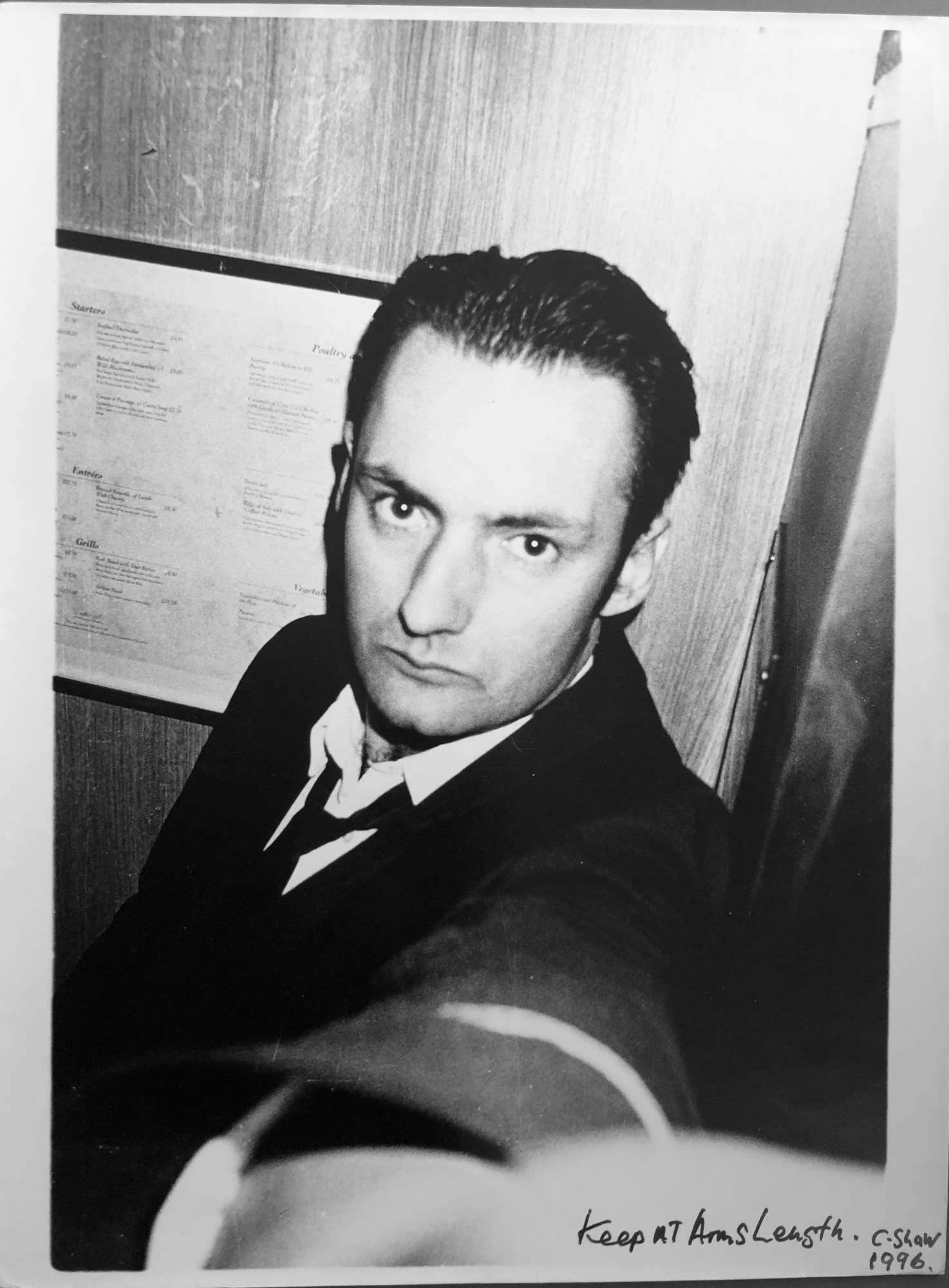

Over the years, Chris amassed a bin bag’s worth of undeveloped prints. “I was under-earning in a menial job and couldn’t afford to make prints myself very often,” he says. “But when I did, my world changed.” For Chris, the dirty work continued in the darkroom, where he leveraged his anonymity and devaluation as a low wage worker into an act of authorial intent. He added stains and thumbprints, amped up the contrast and imbued his pictures with a distinctly personal poeticism by scrawling captions around their borders. “It was all about the physical connection,” he says excitedly. “For me, photography is a very dirty and rough process… Something I felt photographers had lost.” Chris’ was an aesthetic of wilfully “bad” prints. “It’s Night Porter,” he proclaims. “Not Ansel Adams!”

“I entered the Night Porter prints into a fashion photography competition as a bit of a joke,” Chris says. “The judges were Alexander McQueen and Nick Knight, who awarded me first prize and about £10k in prize money, which meant I could fly around and leave the hotels… Well, stay in them, not work in them…” The photographs were later concocted in Life as a Night Porter (2005), a chaotic and thrilling A3 book published by Twin Palms, one of the jewels of the photography publishing world. “I started at the top with Twin Palms,” Chris says. “Back then, they were above a whole bunch of pay-to-play publishers who depended on academics trying to get their work published to justify their moribund academia. So, coming from the lower classes and showing the reality of the working poor, I was never going to pay a publisher.”

Class has always been an entirely necessary consideration for Chris. He recalls the 1981 relaunch of Mass Observation, a project that aimed to study the lives of ordinary people to counteract the stereotypes that held sway in the British media of the time. However, for all their left-leaning sympathies, the group were criticised for their privileged perspectives, viewing the working class as a kind of exotic species to be studied under an anthropological microscope. “In many ways, the ‘movement’ affected British documentary photography,” he says. “It was very class conscious and involved sending middle-class photographers from the South to photograph the working classes in the North. It was almost as if they ignored the unpleasant fact that there are poor people living in London too. Class is a very British thing. Regional accents are always disparaged. It’s just the way it is… There’s often the tendency in documentary photography practice to define working-class people in a cruel way.”

One of the great successes of Chris’ book is how it is seemingly without any cynicism or scepticism. It’s a work diary unlike any other, circling around myriad oppositional dyads: boredom and play; labour and leisure; gritty reality and sexual fantasy. Mixing moments of what Chris calls the “social fantastic” with CCTV shots, performance warning letters and journal entries, Night Porter suggests an approach in which the artist is simultaneously a participant and observer within their own private, semi-imaginary hotel. “My pictures bear little or no resemblance to the actual hotels,” Chris notes. “In my experience, heaven and hell are places right here on earth, and you can stay in either one.”

Chris has since become a curious character in the international photography scene. In 2013, his prints from Night Porter as well as Weeds of Wallasey — a series documenting the post-industrial badlands of the Wirral Peninsula where he grew up — were presented alongside Daidō Moriyama’s nightmarish Tokyo shots at London’s Tate Britain. Curator Simon Baker’s intention was to highlight Chris’ compelling translation of the poetry and passion of Provoke (the Japanese photographic collective of the 1960s) into a very British context. But while his alignment with Provoke’s protagonists (he adds Eikoh Hosoe and Ikko Narahara to his list of heroes too) has made him a collector’s darling, Chris has always felt more confident outside the gallery ghetto, and remains resolutely his own man. “I don’t teach. I’ve never done journalistic work. I still make and sell my own prints without a gallery, which is something I always wanted to do. The fact Martin Parr once told me that this was impossible only made me want to do it even more.”

“I don’t regret my past,” Chris continues. “It’s like a Persian carpet… When the carpet’s being made, there are lots of mistakes. But when the carpet’s finished, it looks like those ‘mistakes’ are part of the design. I’m 60 now, and I can see that I was, in many ways, already a photographer back then. I was given a subject, and it was pure chaos.”

Credits

All images courtesy Chris Shaw