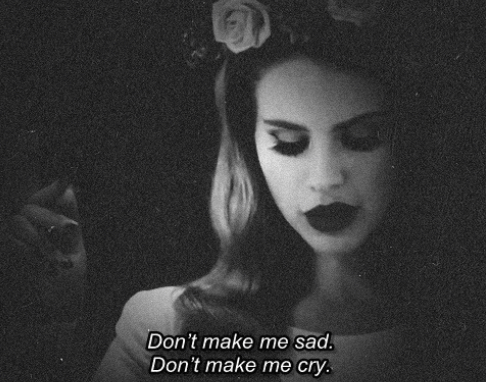

If you’ve heard the term “Sad Girl” recently, it’s probably in reference to Lana Del Rey, queen of pop melancholy who has inspired a million #PrettyWhenYouCry selfies. It could have been on Tumblr, too, where lately teen angst manifests as dip-dye braids and soft-focus bruises. Actually, when you think about it, Sad Girls are everywhere—in the musings of Twitter personality @SoSadToday, the selfies of artist Audrey Wollen, creator of “Sad Girl Theory,” and on Etsy, where you can buy Sad Girl necklaces, pins, vests, and tote bags, typically in pastel.

Like many things on the Internet, Sad Girl became a brand and a think piece before it was a sentient cultural movement. But it’s no health goth—the term describes real people with identifiable qualities. Sad Girls are young women, likely in affluent Western countries, who spend time online and embody a particular paradox: the desire to express their deepest interior feelings through an aesthetic many consider formulaic (waifish frames, cursive tattoos).

Twenty years ago, the last time the term “Sad Girl” circulated through the pop-culture lexicon, it evoked a very different community, one more likely to have prison stick-n-pokes and teased bangs than periwinkle plaits. In the 1994 movie Mi Vida Loca, “Sad Girl” is an L.A. chola, whose fellow girl-gang members tattoo the nickname to her knuckles when she joins. At first, Sad Girl, real name Mona, doesn’t think it’s a good fit, but after her lover gets her and her best friend pregnant then is killed in a botched drug deal, she grows into it. Sad Girl’s style encapsulates her name: three teardrop tattoos adorn her cheekbone, and in every scene, she wears dark purple lipstick.

1994 Echo Parque couldn’t be more different from 2015 Tumblr. Yet vestiges of the original Sad Girl style linger. In a segment of her 2013 music video/short film “Tropico,” Lana Del Rey plays an L.A. stripper with a gangster boyfriend, wearing door-knocker earrings and (paint-on) teardrops tattoos. Sad Girls Y Qué, a Tijuana-based feminist art collective, called it appropriation. “She is this blonde heiress, [taking] all these symbols from a culture that isn’t hers to make profit. It’s obviously offensive,” they told Wonderland Magazine. The collective, which takes its name from Mi Vida Loca, thinks the Sad Girl archetype shouldn’t be divorced from its origins within a macho, Catholic society that oppresses women in specific ways, they told Vice. By reclaiming the archetype, Sad Girls Y Qué are opposing a particular iteration of the patriarchy, not just reblogging bruise pics because its members are in a bad mood.

Curiously, though, much of Sad Girls Y Qué’s imagery fits perfectly into the larger Sad Girl zeitgeist. On the group’s website, Sailor Moon drawings, pink charm bracelets, and waifish girls in body glitter abound, as they do on Tumblr tags #pale grunge and #pastel goth. The difference is, these tags have attracted criticism because their images rarely show skin colors any darker than pale, as writer Rosemary Kirton points out. This doesn’t mean that only white people are posting and reblogging them, or even that users are consciously racist. Rather, it signifies a collective desire to prune one’s online aesthetic to fit narrow, and thus exclusionary, beauty ideals. As a contributor to the online project Sad Girls Guide wrote in a manifesto on the site, when she fell into depression while studying abroad, she found comfort in people on the Internet who shared her tastes: “[The Sad Girl] listens to better music than you and might spend her alone time watching French films from the ’60s or angsty TV shows from the ’90s.”

Should an emotion like sadness—dangerously close to the sensitive territory of mental illness—ever be expressed through something as frivolous as taste? Many commenters thought not. “As one of the less-Tumblr-friendly ‘sad girls’ who finds herself spiraling into panic attacks for no discernible reason, I can’t say I really ‘get’ the sudden glamorizing,”’ snarled one reader. “My sadness doesn’t manifest itself as a killer sense of style and an obsession with French films,” quipped another.

Channeling depression into beauty through creative practice isn’t new. It’s an age-old coping mechanism that social media merely makes accessible. Meanwhile, many of the most famous works of literature aestheticize sadness, from Romeo and Juliet to the poetry of Emily Dickinson to Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides. In that novel from 1993, a family of suburban teen girls commit group suicide, a tragic and alluring spectacle to the boys next door who narrate the story. In many ways, the book (and its Sofia Coppola film adaptation) is a proto-Sad Girl text, written decades before smart phones made voyeurism inescapable.

So why do Eugenides and Coppola get to explore the artful edge of suicide when teen girls on the Internet who do so are considered superficial and narcissistic? Because their books and films are of higher quality than your average 16-year-old’s blog, but also because teen girls’ artistic interests—from 18th century epistolary novels to blogging—have never been taken as seriously as they should be. Or, as Audrey Wollen puts it, teen girls have long been “silenced, oppressed, and brutalized” by systems of power. For her, the Sad Girl is a way to protest this fact. Feminine sadness, she tells me, should be read as resistance even though it acts passively “through internalization rather than externalization, through violence against their bodies instead of public space, through weeping instead of shouting.” In one series, Wollen poses nude for selfies that resemble famous historical paintings originally done by men. “We can use the products of oppression as the tools to dismantle it,” she told i-D last year.

From this perspective, Sad Girls existed long before Molly Soda, Fiona Apple, Mi Vida Loca, and Emily Dickinson—and will continue existing long after. “There is no point of origin,” says Wollen. “There was no time before girlness, and there certainly was no time before sadness.” Like a recycled Tumblr image, the Sad Girl is fluid and constantly morphing—and maybe that’s not so bad.

Related: How Richard Prince Wronged Sad Girl Audrey Wollen

Credits

Text Alice Hines