“I believe that as Black people we should be acknowledging our roots but from there onwards we have the right to express our own individuality. When we begin to allow Black people to be free of repressive conditioning, intolerance and self-imposed limitation, when the Black man and woman can act without fear of letting the Black race down, we will begin to see an end to institutional racism.” — Joe Casely-Hayford OBE, i-D #124, January 1994.

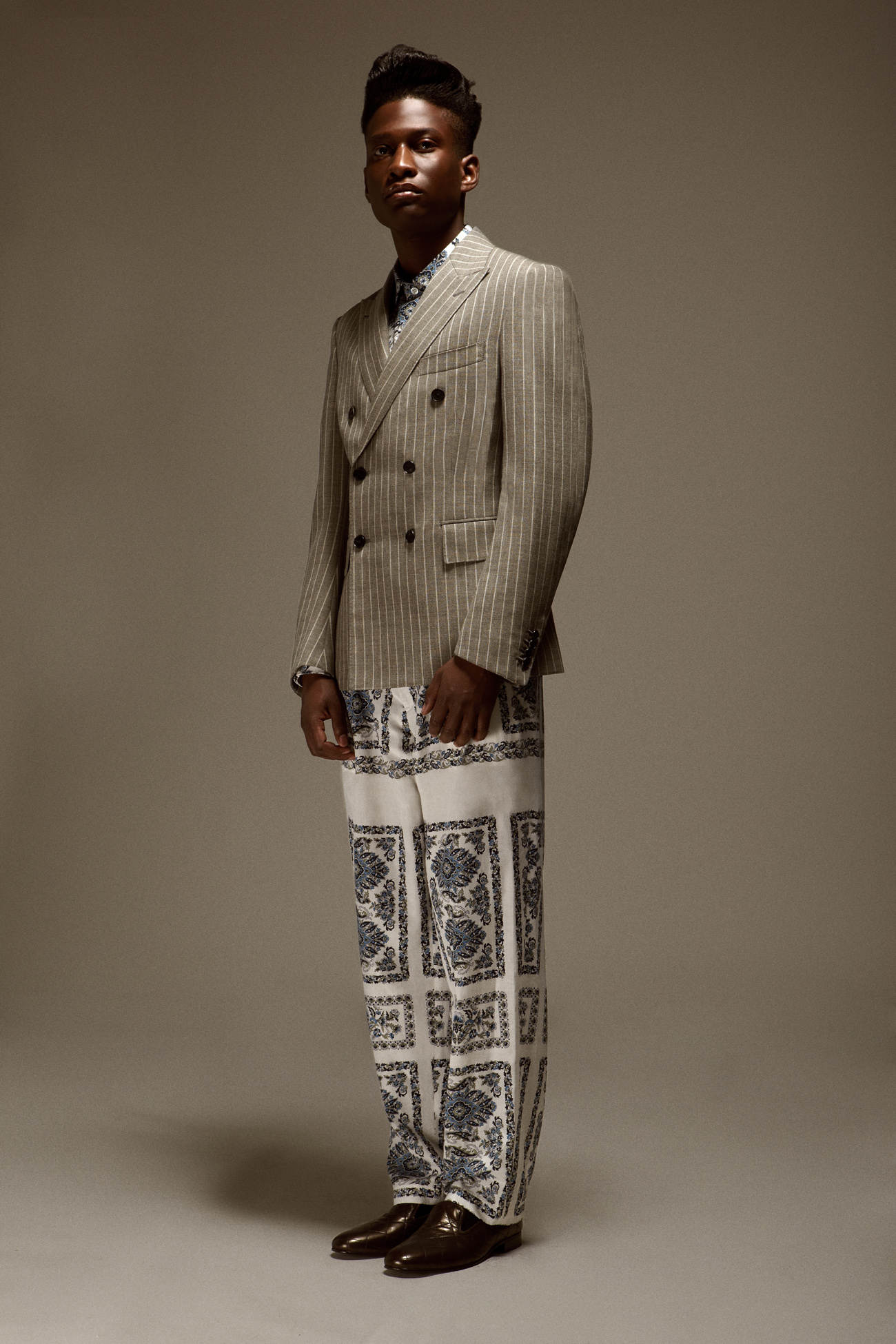

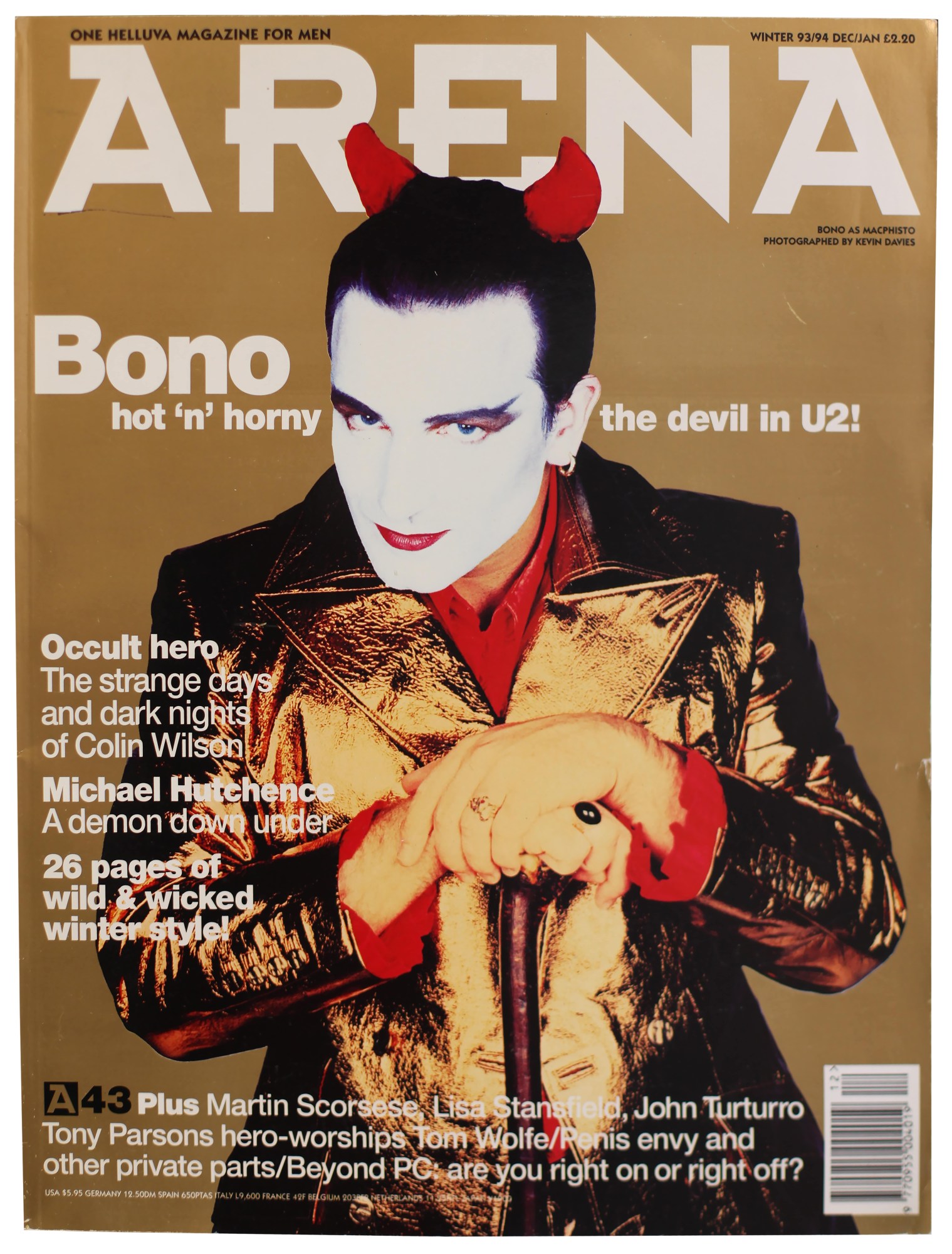

Achieving cult status through both his craft and charisma, the late Joe Casely-Hayford (1956-2019) dominated the 80s and 90s to build and maintain a vibrant, international fashion brand, occupying the world stage for four decades with his wife Maria. Upcycling fabrics as early as 1983, and the first to be selected by Topshop for their groundbreaking designer collaborations in 1993, Casely-Hayford, a polymath, undertook bespoke commissions for bands and artists including The Clash and Lou Reed while also consulting on film and ballet projects. When U2 employed him as creative director for two non-stop world tours and two albums, he produced easily the most memorable looks to catapult the band’s lead singer Bono onto the front covers of era-defining magazines. After a three-year post as Creative Director of Savile Row’s Gieves & Hawkes, beginning in 2005, a new era beckoned. Casely-Hayford, the brand, was established with son Charlie in 2009 and continues to this day.

“As a young Black man interested in style and creative culture, you’re looking for heroes,” says Andrew Ibi, designer and academic. “Whether it’s football, art or fashion, iconic leaders drive progress. There was Bruce Oldfield, but with Joe Casely-Hayford, suddenly I felt like this game was for us. And when, as a fashion graduate, Joe called me to discuss an assistant position, it was like hearing from my ultimate hero.

“He’d set almost impossible tasks for each new collection, starting with the questions: ‘What are we looking at? What is the thing?’ I would go out and cobble together all this imagery and find books in the library. I’d stand on the street trying to observe something that would be pivotal to give me a lead. It was like being an investigator that would take you to a book, a story or a narrative. He’d say, ‘You are my eyes out there’. There was nothing he wasn’t interested in. He’d see new meanings in things I brought to him.

“It wasn’t just how something looked, but its ingredients and components and, of course, its provenance. I had to create big picture ideas through research development, subversion and connecting to culture and society. Joe taught me that what is on my plate as a designer is everything. And that’s why he was so good.”

“Finding new meaning was really exhilarating for my father,” agrees Charlie Casely-Hayford, designer and CEO. “He’d soak up everything around him. He engaged with culture on so many levels. Yet despite his knowledge and his experience he was always very willing to unlearn. I respected him so much for showing me that it was possible to see life through another lens.

“We became fascinated by ideas of identity,” he continues, “looking at ways to break down inherited selves in order to recreate. Rebuilding yourself and your ideas to find a new perspective is a wonderful way to go through life because it keeps things interesting. It was a real learning curve for me, to not approach life in the linear way that formal education prescribes.”

“Joe empowered me to feel that developing as a creative was within my grasp,” agrees creative director Harris Elliott. “His designs were so inventive, containing many subtle twists that could completely change the way that you’d perceive a piece of design for the future. He’d combine quintessential examples of Britishness with the Rastafarian Lion of Judah, for instance. He integrated playing cards — the clubs, diamonds, heart and spades — into his logo. Then there was his choice of textiles. Tweeds, waxes and wools, fusing British subcultures and African cultures.”

“In the early days, Joe did a lot of styling to finance the brand,” remembers commentator and writer Jason Jules. “He worked with 4th On Broadway, the hottest label on Island Records at the time. Everyone from Mica Paris to Duran Duran got the treatment. Later in 92, he visually rebooted U2. A mercurial look dubbed The Fly, modelled by Bono with a little help from Christy Turlington, graced a Vogue cover. The following year, bedecked in gold and embodying an alter-ego named MacPhisto, in a take on Goethe’s Faust Mephistopheles — a fallen angel figure, Bono would adorn one of the most memorable Arena covers.

“These storytelling skills added a wow factor to Joe’s runway presentations. The clothes themselves weren’t outlandish or extreme — on the contrary, they were elegant and always immaculately constructed — but it was the ideology underpinning his approach to design that gave any presentation he put on a sense of defiance that was often as audacious as it was subtle.

“When he unveiled the Black Panther collection in 1991, there was a lot of cultural tension. Black radicalism was making an impact in music and film, and Black consciousness was powerful currency. While fashion, especially London fashion, was oblivious, Joe created a space for those who of us who were looking for the conversation to acknowledge race complexities and underlying truths. Essentially, he took a huge risk, that his audience would get it and relate to his ideas rather than choosing to be offended.

“A perpetual declaration for Joe was the right to be an individual. He was a quiet but incisive speaker, and an accomplished writer able to investigate internalised stereotypes and tropes. Speaking to The Los Angeles Times in 1990 he explained: ‘If I weren’t Black my business would be three times larger by now. But I want to be successful without having to apologise for my race. I want to do it with dignity and not take the rolling-eyes approach of some other Black designers.’”

“He never wanted to be referenced as a Black designer,” agrees Harris. “Simply, a designer who happened to be Black. He wanted the right to live his life according to his beliefs. He was quiet and reserved, yet so powerful.”

“Those who were previously seen as the disadvantaged minority have developed a unique vision. A new combination of talents has emerged from the fertile ethnic exchange of cultures. Increasing numbers of Black people have this capacity to draw from and enrich both cultures whereas the reverse is impossible. The majority culture has never felt the need to educate itself fully nor enrich itself with anything other than the western ideal.” – Joe Casely-Hayford OBE, i-D #124, January 1994.

“At first I didn’t really understand how race barriers manifested for Joe’s business,” says Andrew. “He had such cult status I couldn’t see it.” “It’s still amazing to think that Joe never won a fashion award,” says Harris, “we all watched him negotiate exclusion from an industry that promotes and perpetuates the notion that fashion is open for all but instead adopts the attitude that it can just take whatever it wants and claim ownership. That’s not inspiration. That’s theft. It’s time to challenge fashion houses who help themselves to Black culture whilst rejecting Black models in their shows, Black designers in their teams or Black CEOs in their boardrooms.”

“Becoming Consultant Creative Director at Gieves & Hawkes in 2005, was a real moment in fashion,” remembers Andrew. “I’m not sure if the organisation understood what they had in Joe. And yet, to so many of us, it made perfect sense.”

“He was always true to himself, refusing to adhere to any restrictive ideas around definitions of Blackness. The background or status of others didn’t seem to register,” says Jason. “He valued everyone as an individual and would relate to each person from a totally egalitarian perspective — no hierarchies. He would give as much time to the intern as the CEO. Even his studio, a high-ceilinged building just off a busy, inner-city high street was an oasis of culture. Stepping out of the noise and into the tranquillity of a postmodern interior, evoking a Victorian library where cutting tables were surrounded by books, there would be a team of incredibly stylish people quietly beavering away with Joe and Maria calmly at the helm of it all.”

“Joe defined many aspects of Black culture, Black success and the Black struggle at the same time,” says Andrew. “We saw his drive, his tenacity and also his excellence under pressure. He was a man with great principles and integrity and he never ever left those behind. Joe Casely-Hayford was as important as McQueen, Yohji and Westwood because he was telling a story that wasn’t being told by anyone else. His work, along with the mechanism of racism which drove fashion through the 80s, 90s and 00s, is part of fashion history. Black students in particular need to know about Joe because, in anything we do, we need roots and context. If you’re a musician and you’re doing hip-hop right now, there’s no way you wouldn’t understand the origins of your work.”

Collaborating with i-D to deliver this vital Joe Casely-Hayford archive is just one of the ways Andrew Ibi, Harris Elliott and Jason Jules; co-founders of the Black Oriented Legacy Development Agency (BOLD) are actioning change, consulting across fashion and advertising culture to amplify authentic race narratives. Working closely with the British Fashion Council and partnering with the Institute of Positive Fashion, BOLD will continue to initiate developments for the Joe Casely-Hayford legacy. One is working towards a dedicated library of Black fashion literature at Central Saint Martins, Joe’s alma mater (1975–77), where he met Maria to forge their lifelong partnership. Others are in the pipeline. Confirmed for later this month is a special SHOWstudio panel dedicated to Joe and his vision, chaired by Andrew Ibi with Karen Binns, Walé Adeyemi and Ekow Eshun among others at 4pm UK time on 28 October.

“In the limited vision of white society, to unapologetically acknowledge my Blackness is to diminish my professional role and social cultural contribution.” – Joe Casely-Hayford OBE, i-D #124, January 1994.

“Once we accept the unequal playing field where so many overlooked individuals and groups of people were sidelined,” states Andrew, “we can create factually correct historical archives. These are journeys of creativity that Black designers are missing when mainstream editorial and academia promotes mostly white achievement.”

Another initiative inspired by Joe’s legacy is Fashion Academics Creating Equality. Created earlier this year, FACE is supported by i-D, SHOWstudio and Graduate Fashion Week. Its members will challenge current educational protocol that centres whiteness, white knowledge and white leadership to support future generations of Black talent in a way that wasn’t there for Joe or others since. One example of race myopia is the inequality of professorial posts. Recent UK data has numbered Black female professors at 25 while there are 15,700 white male equivalents. By prioritising diverse educational perspectives, FACE will elevate the creativity of Black students and academics so that everyone can understand and protect against the theft and exclusion of Black culture in the future.

“I want students to learn about the industry,” says Andrew. “I don’t mean business; I mean the culture of the industry. In the future I see all students questioning why fashion was so racist. Thanks to Joe Casely-Hayford and his story, we now have the Bianca Saunders story, the Nicholas Daley story, the Grace Wales Bonner story.”

Joe Casely-Hayford’s life has inspired, and will continue to inspire, many creatives to reach for their dreams on their own terms. Acknowledgement of this expansive legacy is best led by his daughter, Alice Casely-Hayford.

“My beloved dad has been the biggest influence on my life and will forever continue to be. Growing up in our parents’ studio, it was enthralling to watch him at work, so quietly powerful and commanding in the most gentle way. As immensely proud as I am of his work and contribution to fashion, his most important role, that he cherished above all else, was as a husband and a father. Uninterested in the spotlight or the social scene, he was incredibly devoted, instilling us with the value of family and integrity.

“Dad was my biggest champion, encouraging me through everything from micro wins to huge life achievements. He so readily championed and supported others with such a generosity of spirit and that was one of the greatest lessons he taught me, one that I try to live by both professionally and personally each day. Always give credit where it’s due and raise others up. It has been heart-warming and comforting to learn of the amount of people dad touched with that same generous, supportive and inclusive spirit. Despite having so many doors closed to him, he never ceased to open the door for others. It’s a constant struggle without him as a guiding light but I’m committed to continuing his work of making space for others and giving a platform or support to those who need it. Thank you, pa, from all of us.”

Edward Enninful OBE, Editor-in-Chief of British Vogue: “Joe and I come from the same time — and he was one of our generation’s foremost pioneers: the first Black designer who represented London on the world stage. His ability to both reflect and subvert the tropes of contemporary fashion, from tailoring to streetwear, was consistently impressive — but even more important was the generous, open-minded spirit which he was always renowned for, both by this industry and anyone who ever crossed his path. His legacy is felt throughout this city — and is carried into the future by his remarkable children, Charlie and Alice.”

Sir David Adjaye OBE RA, Architect: “Joe was a trailblazer who shattered the creative industry’s glass ceiling, making way for people of colour to imagine ourselves actively within the profession. As a young student in the 80s, there was simply no other person I could remember from that time that represented such bold innovation and Black radical creativity not only in the UK but abroad. When meeting him I was struck by his humbleness and the brightness of his soul. I have the utmost admiration for him. He is truly a public role model and forerunner in his dignity.”

Elgar Johnson, Deputy Editor and Fashion Director of British GQ Style: “As a young person working within the fashion industry, it is incredibly daunting. As a young person of colour working within the fashion industry, this is a whole different level of trauma. Joe Casely-Hayford was and still is a beacon of hope for any person of colour.

I first met Joe when I was a model and I went for a casting to his show and I, like my white model friends, was blown away sadly not by the clothes — which, incidentally, were extraordinary — but by the fact he was a Black man. The impact was instant. Joe was the first person of colour I had met in the fashion industry.

My friends instantly assumed I would book that show because ‘I was his type’. I didn’t book the show, because Joe was a man and designer that had a vision that didn’t include race, gender and background. His vision was much bigger and is something we can all learn from.”

Sir Paul Smith CBE RDI, Designer: “I always had the utmost respect for Joe and for his work. He was always discreet and low key, but he was a gentleman and always looked very smart and very stylish. His quiet way sometimes meant he went under the radar or unnoticed and when he was eventually recognised by Buckingham Palace with his OBE, I remember saying ‘about time!’ which was absolutely the case.

The point about Joe was that he was real. He was real and he really knew his job. Often people in the fashion industry are good at the front of house bit or good at doing extreme or attention-seeking clothing but not the hard work that goes on behind the scenes. Joe and I had in common an appreciation of construction, how good clothes are made and the importance of hard work.”

Johnnie Sapong, Hairdresser: “Medasse Pa!! Joe Casely Hayford. A gentleman, a scholar and a true artisan. The Don Dadda, Paramount chief, loving husband and proud father. I miss you JCH and give thanks and praise that I had the pleasure and joy to collaborate with you. i-D magazine in the 90s, it was either a straight-up or back page shoot for a t-shirt Joe had designed (might have said Love!?!). We shot at Joe’s studio on Endell St. and he did the styling and Donald Milne shot it. A total touch of class with a punky edge. Love, Light and Global Unity.”

Cynthia Lawrence John, Stylist, Costume Designer and Consultant: “I remember when I started styling my own shoots and I’d visit the studio, what I loved was that Joe always had time to just come and speak to you. I would learn so much from him — just telling me about some of the details that went into the collection and the ideas. I really appreciated that even if you were new, a bit wet behind the ears, he would afford you so much respect and simply speak to you. And as a young Black girl at the time, that was really important — especially when a lot of other designers and people working in fashion wouldn’t even look at you, wouldn’t even acknowledge the fact that you’re breathing in the same space as them. But he would always make time. Even up until when he was ill, when I last saw him, he would always make time to talk to me about something he’d liked or something of mine he’d seen. That’s what I think the main thing about him was — he was very human and he liked to engage with you, but on a real level.

He was honestly just an inspiration — obviously when I first started there were very few people of colour within the fashion industry, so he was very much somebody I looked up to. I always loved the fact that he was able to make something as simple as a pair of men’s trousers and add a detail in there that was never gimmicky, always very clever, always really interesting, and always a concept behind it — never done for the sake of it. He knew his craft, which is what I always loved about him, he had an absolute knowledge of tailoring.”

Nicholas Daley, Designer: “I remember attending Charlie and Joe’s first runway show during my studies at CSM over LFWM. It had a powerful effect on me to see a Black British father-son duo of designers showcasing their collection, which at the time, gave me hope that I too could reach that level.

Joe created a blueprint for future generations of designers like myself, selling our collections in Japan. My very first stockist, BEAMS in Japan, also stocked Joe’s collections a whole decade before which paved the way for other Black designers to sell their collections in such prestigious stores.

Joe was a true pioneer in every sense: in his approach to his designs, as a creative director of a Savile Row house, being awarded an OBE and launching a collaborative collection with his son Charlie. His legacy should be highlighted to future generations of British designers as he has been an inspiration for me and other Black designers from my generation.”

Karen Binns, Fashion Director and Publisher & Editor of WHAT Magazine: “Joe was the perfect example of how a person of colour should enter into the fashion world. When you looked at the work you didn’t say ‘this is the work of an African guy’, you said ‘this is the work of a world travelled guy interested in culture and good taste who happens to be Ghanaian’. For me, this is one of the most important things. What is a designer from a culture? He will always have that much more to give because he has culture and the richness of that culture affords him the category of good taste.

We, as people of colour, have got to challenge the way we are categorised and ‘othered’. Doing this to us gives some a sense of safety, as if we could never compete on the same playing field. Well, watch the fuck out; we’re always going to be more motivated because we have something extra. We have the richness of culture. And within that culture is also pain, as well as achievement out of pain. We have struggles that others will never ever understand; it’s not something you can buy. There is no luxury without culture and that explains the existence of Joe Casely-Hayford’s legacy.

He was an extreme trailblazer on trends. Today, regardless of what colour the designer is, we are still seeing the influence of what Joe Casely-Hayford offered to the fashion industry. All this sports luxe? He did it already — and did it better! Others cannot match him because they fail to dig as deeply into what culture really means. That’s how I feel about Joe. That, and the fact that me and a lot of other women had a very big crush on him!”

Ekow Eshun, Author, Broadcaster and Curator: “Joe was an inspiration to me even before I met him. If you were growing up as a Black person in Britain in the 1980s, your identity was presented to you as a binary choice. You were either Black or British, assimilated into the mainstream or an alienated outsider.

Seeing Joe’s work in The Face and i-D was thrilling. It changed how I saw the world. Joe’s designs were informed by a cosmopolitan sensibility that made clear you could be both Black and British at once without compromise. Identity, as he seemed to envisage it, was not a fixed position defined by colour, culture or class. It was a state of perpetual possibility, a condition, as the scholar Stuart Hall put it, of ‘becoming as well as ‘being’.

Context-wise we should situate Joe within a generation of extraordinary Black creative figures that first came to the fore in Britain during the 1980s: filmmakers like John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien; writers such as Ben Okri and Caryl Phillips; visual artists including Lubaina Himid and Sonia Boyce. Collectively they mapped out a new terrain of artistic complexity and sophistication that established Black Britain as a cultural space for the first time in this country’s history.

Even more than the work he did, Joe was inspiring to me as an individual. I felt a connection with him through a shared heritage — his family came from the same town in Ghana as mine. I admired the way he carried himself with such elegance and self-possession. And how he oriented himself by a personal vision that he never seemed to lose sight of. From the first time I met him I wanted to emulate his path. And to this day I still do.”

Jazzie B “Funki Dred”, founder of Soul II Soul: “Meeting Joe for the first time in the mid-eighties He seemed so shy, yet so sure.

Joe had the skills of a Savile Row tailor and the imagination of London’s street culture in the 1980s, putting the two together gave his clothes a classlessness that was key to those times, and showed the world that provided you understand the structure and the fine detail of what you’re doing you can make anything work. High fashion skirts out of army surplus tents? Why not?

Joe should be honoured because as a young Black man in London he succeeded in a world not known for its inclusivity and did so on his own terms; he presented an alternative narrative to the idea that Black people in the UK are downtrodden and waiting to be helped. Joe had a lot of swagger about him.”

Harriet Quick, Writer, Consultant and Contributor to British Vogue: “I have clear memories of visiting Joe Casely-Hayford in the mid-nineties when he was showing his collection as part of a small group of London brands and designers in Spitalfields Market, Shoreditch. Back then the East End was ramshackle and occupied by artists and creatives benefitting from the cheap warehousing space. There was not a barista in sight, but Casely-Hayford certainly delivered on style.

As the then-Fashion Editor of Fashion Weekly and contributor to i-D, my role was to report on fashion yet my knowledge of menswear was slim. Casely-Hayford, always impeccably turned out, took the time to educate me in the sartorial codes that defined his brand — a fusion of traditional Savile Row techniques, British–Ghanaian sensibility and a sharp-witted spirit. I learnt about worsted wools, heritage checks, tweeds and the semiotic secrets that he embedded in the pattern cutting, in the linings and pocket detailing. His insistence on elegance was in sharp relief to the sportswear and clubwear championed by his peers, including The Duffer of St George and John Richmond, yet you could sense a great deal of camaraderie between London menswear designers.

I had my own taste of Casely-Hayford tailoring in the shape of a sharp-shouldered grey frock coat that he kindly gifted to me. It became a uniform piece coupled with a slip dress on my trips to the Paris and Milan shows. Casely-Hayford’s methodology has impacted on future generations of designers who now nimbly mix codes of dressing and transmute their own stories and cultural references into collections. Casely-Hayford was always a pleasure to talk to: a man with immense integrity who appreciated how clothes can help one stand tall in this world. That lineage is being kept alive via his son, Charlie, at the eponymous Chiltern Street store.”

Bernice Brobbey, Men’s Model Agent at First Boutique Model Agency: “He didn’t have to go and discover himself later. Unlike other designers, Joe knew who he was and where he was from and how to navigate through this environment. Appreciating other cultures, being inclusive of other cultures and influences doesn’t mean you think any less of your own or your work is any less authentic — Joe demonstrated that personally and professionally and his creativity embodied that in such a deep, beautiful way.

Back in the 90s we, as Black people, were blocked; it may not have been named as such then, but we were having to deal with what’s now recognised as covert racism. As a real pioneer in British fashion, Joe had a quintessential style and an amazing design approach. He should have got a major fashion award (and so much more recognition) but he simply didn’t fit the criteria. I think Joe dealt with racism on a level where it didn’t matter how chic or talented you were, it just came down to the colour of your skin.”

Dean Ricketts, founder of The Watch-Men Agency: “This is so difficult for me but any words would have to be in celebration of the ‘house’ that Joe and Maria Casely-Hayford built. Inextricably linked in marriage and business, they created a ‘home’, in modern times a ‘safe space’ for us creative newbies. They are my fashion family who taught me — subtly, of course — professionalism, tips on styling and art direction, who gave me a ‘heads up’ on books and records that I should read/listen to. But more importantly, they showed me how to contextualise our African/Black cultural heritage. I call it the ‘House of Hayford’, the signature is so strong it’s passed on seamlessly to all their children.”

Terry Jones MBE, founder of i-D and Editor-in-Chief 1980-2012: “I first met Joe and his wife Maria during London Fashion Week, sometime in the mid-80s. The i-D stall was relegated to the upstairs gallery at Olympia Hall, the British Fashion Council’s venue for a couple of the years that British designers were emerging onto the international scene.

I had been introduced to the Casely-Hayford label by Stuart Malloy who owned the highly reputable fashion destination Jones, in the prime spot on the King’s Road London.

Tricia spotted a fabulous heavy cotton white shirt she loved and we were really happy when we met Joe and Maria in person. Both extremely smart, stylish and calmly cool. The i-D corner was loud with a crazy TV totem in papier mache by Georgette Franks, blasting out our raw videomash, much to the annoyance of BFC officials.”

Caroline Rush CBE, Chief Executive of the British Fashion Council: “Joe was a game-changer. I think I first saw his collections in Jones on Floral Street in Covent Garden, which in the late 80s/early 90s was one of London’s emporiums for those seeking out the best global designer collections. You could see the influence he was having on menswear, on the way men dressed and still do today. But now, reflecting back on his design journey, his great understanding of culture and love of creative industries it is essential that Joe’s own creative cultural legacy is recognised and he is remembered with great reverence as being one of the all-time greats of British fashion’.

Eddie Prendergast, co-founder of The Duffer Of St George & Present London: “There was a time when only a few people stocked him in London, but we always did. Like Peter at Jones, we got it, we recognised that it was art — he was an artist. Very few menswear designers can be put in that category without their work becoming quirky or too fashionable, but Joe was a designer who managed to totally elevate menswear by introducing imaginative, tasteful touches. One thing he always maintained, protected even, was his creative integrity. I think he had plenty of opportunities to sell-out, but he never did.”

Sarah Mower MBE, International Fashion Critic and Columnist: “When I was writing for Honey Magazine in the 80s I came upon Joe’s Brick Lane collection and was awestruck by his use of WWII tents to make clothes which utilised London East End cultural references to compliment his extremely skilled tailoring. All of that pioneered what is now called upcycling and representation.”

Charlie Allen, Designer and Bespoke Tailor: “Despite practically being neighbours, Joe and I would meet in the oddest of places! Once, meeting by coincidence in Japan, we sat catching up over drinks for hours. After leaving to catch a train, I looked out the carriage window and noticed a giant billboard with Joe advertising Japanese whisky in the middle of Tokyo! I had no clue that was the reason he was in Japan but that element of surprise, was him all over. Moving in silence was always his special trick!

As a young Black designer in the 80s, when no one took menswear seriously, it was always comforting and motivating to see Joe succeeding in new spaces. Everyone would look out for what Joe was doing. Years ahead of his time, he helped shape and develop menswear, taking it to the place it is now.”

Chris Amfo, Stylist & Designer: “I was a styling assistant to the Casely-Hayford brand for the Spring/Summer 2010 season collection. I would spend late nights with Joe and Charlie at their studio on Kingsland Road putting looks together. Joe would always return from the corner shop with cans of beer and Supermalt to keep us going as tiredness kicked in! Joe had an amazing archive of books and magazines at the studio, ready to enlighten us with original cultural references and imagery from older JCH collections.

If there was something that others might emulate or learn from Joe’s approach, it would be that a whisper can be louder than a shout. I think it’s important that his contribution to British fashion is remembered and honoured because his work as a designer and stylist has been influential to so many in British fashion as well as music, having worked with various iconic acts. When we discuss the trailblazers and pioneers in British fashion Joe Casely-Hayford’s name should always be mentioned.”

Dylan Jones OBE, Editor-In-Chief of British GQ: “The thing I always liked about Joe was his quiet energy, and the way in which he developed his style and his process without being in the least bit demonstrative. He added a huge amount to the culture without shouting about it and without being flashy, which is why I think so many people liked him, and one of the many reasons he was taken so seriously as a designer. He came of age at a time in London when bohemian values were celebrated above all else, and when culture was deemed to be more important than the intrusion of success or the complication of media. Lovely man, important man.”

Priya Ahluwalia, Designer: “I can’t put a finger on the first time I heard Joe Casely-Hayford’s name but I remember knowing of him and his work as a child. I knew he was so special within the Black community as there was really no one else with such a successful and large platform from the community working in fashion in London. My family used to talk of his work and I remember people around me owning his pieces. I consciously learnt about his work as soon as I knew I wanted to work in fashion.

His work was always wonderfully exquisite and so tasteful, but through his unique use of prints and graphics, it was always fun at the same time. Beyond his incredible talent, beautiful designs and business acumen, I really believe he paved the way for Black creatives in Fashion in London during some of the most racially-charged years. He was a class act, in the face of a society that was not built for people like him to succeed and his representation was key. I know that personally when I was a teenager, seeing Joe and his son Charlie being so successful as designers, made me think that against the odds, I could do it too.”

Fintan Fitzgerald, U2 Stylist 1989-1997: “It was the early 90s when I first met Joe. I was U2’s stylist and the band were in the studio working on their album Achtung Baby. I was looking for a designer to collaborate on creating a radical new image that would fit the direction the music and the band were heading in. This was for the album campaign and Zoo TV world tour. I met with a number of designers but none came close to Joe. It seemed to me his practice and aesthetic was informed by a great knowledge and deep understanding of such a vast range of cultures and movements. He had this ability to interwork all these strands together to create something new and fresh yet still be rooted in each respective history. In Joe’s designs you found so many elements threaded together: Savile Row tailoring, rock ‘n’ roll, punk, African textiles and weaving, jazz, soul, street style, you name it. He was an alchemist.

Because of the nature of the Zoo TV live shows, which were forever evolving, new ideas and stage characters were developed and so new costumes were created throughout the tour, including for the follow up album Zooropa. Joe was more than up to the challenge. His work ethic, his grace under pressure, his unerring eye for detail, the fact that everything that came out of his studio was constructed and finished to the very highest standard and built to last — along with his ability to conjure clothing that worked on multiple levels, for performance, visually, for the stage character, for the camera — was extraordinary.

So a job well done Joe. Thanks for the privilege of working with you, for the education, the kindness, the patience, the memories and not least the great clothes!”

Hassan Hajjaj, Contemporary Artist: “I think if Joe was in the US and working in that environment, he may have got much more recognition than he did here. But I don’t think Joe was ever looking for praise. I loved the way he kept himself to himself, with his family at the heart of everything. I loved how he was all about design and how he stuck to what he believed in. When I asked him if I could shoot him for a series of portraits and he said yes, it was such an honour for me — I couldn’t believe it, I was like a kid in a sweet shop.”

David Bradshaw, Stylist and Art Director: “Back in the day I’d strut about London, best togs, portfolio swinging, in pursuance of my trade as a jobbing stylist. To pull things for an editorial in analogue, you had to get out there, and hunt them down.

Fashion showrooms fascinated me, because of their promise to entice, seduce, stimulate. Purpose beyond mere function, 4-D in effect, almost like a second skin to those named above the door, an insight into a creative mind.

Joe’s showroom — always reached via some Dickensian alleyway, daylight momentarily lost, a slight temperature drop, ground beneath feet turning from pavement to cobbles — felt like a portal into an old London, the rest of the city, hurtling head-long and hedonistically toward the millennium, had forgotten. But here, a couple of clicks of a dandy’s cane off the main drag, was Joe’s London — peaceful, contemplative, cultured — an altered state, a gentleness of spirit, a quiet strength, a defiant optimism.

Gieves was a perfectly natural and elegant step for Joe and he went about his time there with the grace we all expected and without a doubt gave this very particular piece of old London a mystic modernism. His AW2006 advertising campaign sees a young dude, part Jagger, part Artful Dodger, louche against the ancient wall carved graffiti of Harrow School. An attitude personified, a smouldering rage beneath the exquisite veneer of a proper dandy.”

Tricia Jones, i-D Original Mum: “I absolutely loved the contribution that Joe made for the Family Future (later to become the Soul i-D) project.

Inside a red heart, he handwrote the names of all the people he regarded as ‘family’ and I will always remember how honoured I felt to find that Terry and my names were in it! It became a full page in the issue. Maria and the Casely-Hayford family are indeed a deeply respected and talented family within the fashion industry.”

Peter Sidell, Fellow at the Royal College of Art & owner of The Library 1994 clothing store in Brompton Cross, Kensington: “Joe was an alchemist, he knew everything about the history of British tailoring but more, specifically men’s tailoring globally. I worked with Joe from the beginning because I went to school with his brother Peter — we were and still are friends; the whole family are remarkable. I was a buyer for Jones on the King’s Road in the early 80s and so I bought Joe’s amazing designs. He attracted a huge amount of attention and people would travel to London to visit the store. They loved what he was doing.”

Tony Chambers, Creative Director, Design Consultant and Editor: “Aside from admiring the work of Joe Casely-Hayford, I appreciated the man himself. He was so gracious and thankful for support and made this known. I was at Wallpaper from 2003-2007, during which time he was at Gieves. It stands out when you get a really heartfelt thank you. Sure, brands will give you a professional thank you but in Joe’s case, it always came direct from him. There was an unforgettable grace and warmth about the way he conducted himself. In an industry that was super tough, where many did not give the best of themselves, Joe stood out as a decent human being, a genuine and truly lovely person. After a meeting with Joe, I was always more optimistic about the industry and indeed life.”

Simon Foxton, Stylist and Art Director: “It was Joe’s warmth, wit and intelligence that always shone through. As a man, he had such humanity, and this was apparent in everything he did. His designs were beautiful, with interesting and intimate details; trends were not high on his list. When someone has the poise and self-assurance to follow their own agenda, you notice.”

Mandi Lennard, Founder of Mandi’s Basement: “In the early 90s, I remember me and my sister sprinting to Topshop when his collaboration with them came out — super quality bondage shirts in black or white, they were perfection, we couldn’t wait to wear them to The Wag that Friday.

Years later, his daughter Alice interned for us when I was in Hoxton Square. It was only after a few weeks that someone mentioned she was Joe’s daughter — I literally couldn’t make eye contact with her after that, it was just such a big deal for me to have her in my world, when back in the 80s, we’d arrive into Victoria coach station from Leeds and head to Jones in Covent Garden in total awe of her dad and his clothing; he was The Godfather of it all.”

James Sleaford, Freelance Fashion Editor: “Styling a Joe Casely-Hayford outfit for a magazine was almost like a rite of passage — it was never a given! It was like joining a family, one of respect and of understanding of what Joe’s design aesthetic was about. And the rewards of earning one’s stripes was access to one of the most creative menswear labels in London. Joe’s combination of tailoring and art were so inspiring that he changed how I looked at menswear. Joe modernised the male wardrobe with funnelled neck coats and jumpers with added shirt material and raw hemmed tailored trousers — it was a cultural infusion of art, music, street and sartorial all in one hit! He was up there with the best of them. He was an amazingly talented, friendly and humble person and I felt very lucky and proud to meet him and to be a part of his creative family.”

Stephen Jones OBE, Milliner: “Joe and I were both at Saint Martin’s at the same time in the late 70s, but we really didn’t know each other. I think we first met on a dance floor in Soho, him all natural, flowing elegance, me feeling like a geek masquerading as a punk.

Wind the clock forward a few years and one day the phone rang — Joe told me of an exciting new project and invited me to create special hats for the clothes he was designing for U2 for their stage show and personal wardrobes. I was completely excited, U2 was one of my favourite bands and Joe made clothes that were cool beyond cool. We did fittings with the band but in fact rarely had the time to meet up and hang out, but regardless we spoke for hours over the phone, both masters at tucking a phone between shoulder and jaw, him cutting cloth and me blocking felt. It was a friendship born out of respect, we were never in each other’s pockets and I have to say when I made hats for his springs/summer 2015 fashion show, they were some of the most precise hats I have ever made, a level of thread by thread, reserved only for Azzedine and Joe.”

Walé Adeyemi MBE, Designer: “Joe was the master of his craft. My first memories of Joe and Maria are of being in their studio in Whitechapel, which is where I did my work experience. This prepared me for everything because it was really important for me at that stage to see a man of colour, an African, doing what Joe was doing. It was something I’d never seen before and it made me realise that this dream, this career path that I wanted to take could turn into a reality. What I saw Maria and Joe doing — the hard work, the dedication — everything they did was to a certain specific standard, which was amazing to watch.

Joe was so humble. He was a real designer and I don’t think he was recognised as much as he should have been. When I was there, he was doing stuff for U2 and all sorts of other bands and his work was flawless but it was never really celebrated like other designers of the time. It was his tailoring and his pattern cutting that really interested me — I mean, it was in another league to be fair. He didn’t have time to sit there and talk, but just watching him, seeing how he conducted himself, that was school right there.”

Cyprian De Coteau, Fashion Stylist and Designer: “Growing up in Trinidad, I read The Face and i-D religiously. When I saw Joe, this beautiful African man in one of the issues, it really inspired me and made me believe that it was all possible. When I came to London and started assisting Simon Foxton, I got to meet Joe and I had to tell him that he was one of the reasons I chose to come to London. Over the years we became associates and it was always just a joy to meet him. Unlike some designers, he was always wearing his own clothes and always looked so fly, so immaculate.

One thing that was a great inspiration for designers like myself was his independence. He never worked for one of those large fashion houses in Paris or Milan, for example, but don’t think for a second it was because he wasn’t asked or approached — and he certainly had the talent to head one of those houses. I think it was because he stood his ground in what he believed and produced the clothes he wanted to produce without any compromise of caveat. He knew what I think people are only learning now — that independence is the greatest luxury you can have.”

Chris Ofili CBE, Painter: “I would usually visit Joe in the afternoon around teatime and I would go directly from my painting studio. It was special going from my own creative space into Joe’s, to continue a train of thought or be given a shortcut to a creative conundrum or dead-end I had reached. He was very encouraging and made me feel that I was doing something that was important aesthetically and politically and that I was making a contribution to a much larger movement. I often felt that Joe had travelled on roads I hadn’t and could give guidance for what I was later to face as a Black man on a creative life path. I feel my perspective on the world was sharpened by having spent time with Joe.

I remember that the studio had a peaceful feel to it, like time standing still, punctuated by his latest musical discoveries and the fading light as the sun set into the evening. I was younger then, too young to embrace that nothing lasts forever, but I am older now and understand and believe that a spirit as pure as Joe’s is everlasting in its effect on the future.”

Nick Knight OBE, Image-maker: “My memories of Joe are that he was always such an elegant and charming man who had a big smile for everyone.

He was an extremely talented man who managed, against the odds, to maintain an independent business and occupy the world stage for 40 years. Throughout this time I have no doubt that Joe will have personally helped countless younger Black creatives navigate their own tricky and biased professional journeys within the industry.”

Terry Ellis, Director of BEAMS fennica: “I looked up to Joe. He was a gentle, thoughtful man who wore his accomplishments lightly. From a distance, he was the most elegant sight imaginable. Up close he was all kindness and humour. As a designer, his clothes were the closest to art I have seen. The things I have from him spend more time hung on walls than in a wardrobe.

His design influences were many and most were unknown to me, but the toughness, intensity and precision of the clothes spoke of Savile Row, Brick Lane, Kyoto and Africa’s diaspora. Joe is always close to me in memory because the Japanese girl I met who was modelling his clothes at a fashion fair in London became my wife.”

The writing fee is donated to FACE.