Before 21-year-old Adedamola Odetara started documenting the everyday lives of queer Nigerians, he had convinced himself that most of his subjects would be unwilling to show their faces. But, as he began shooting the project, to his surprise, this was often not the case. “I was willing to keep my subjects anonymous, but along the line, I realised that a lot more people were willing to show their faces, and that was interesting to me,” Adedamola tells me.

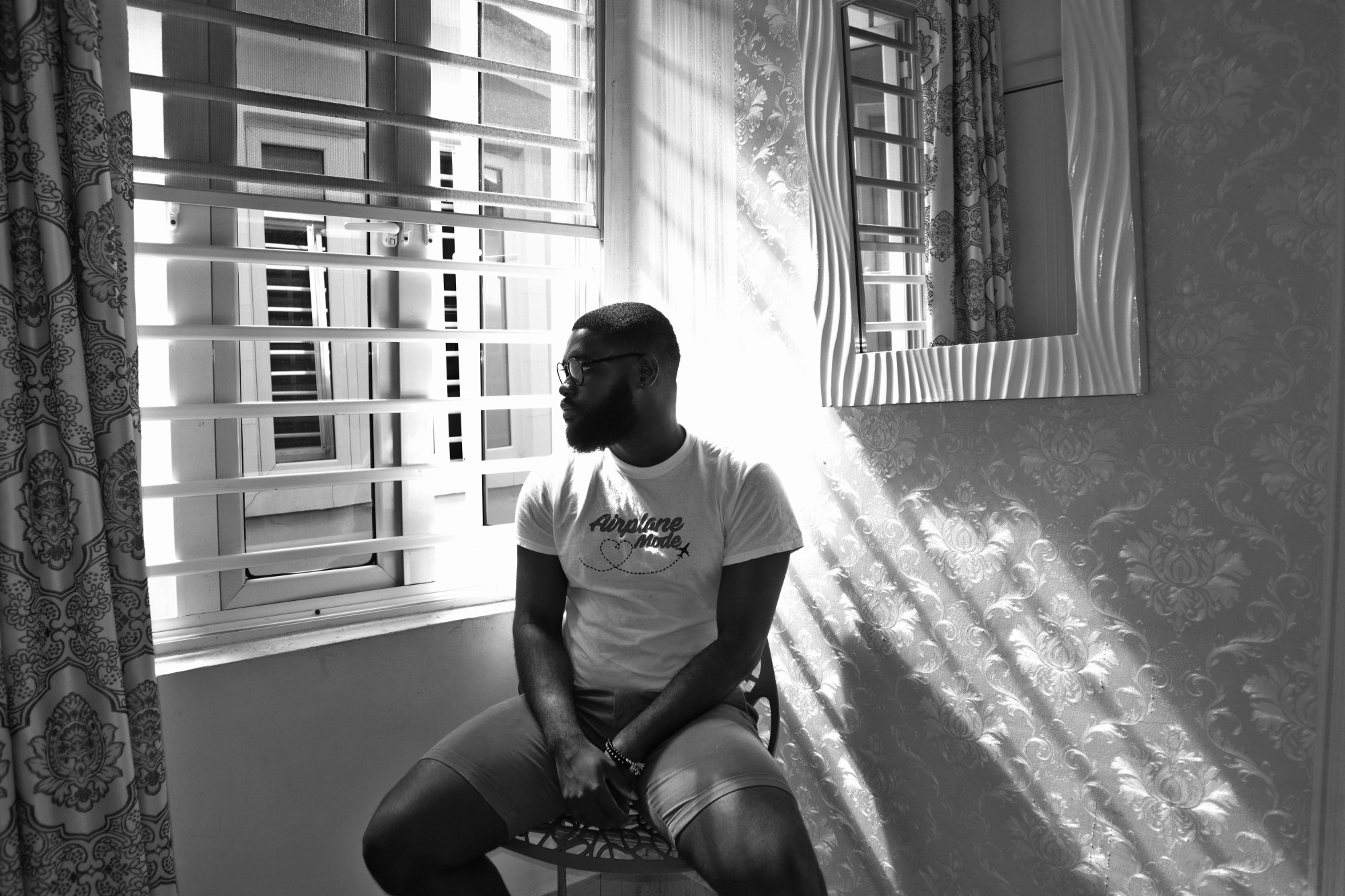

In Adedamola’s project, tentatively titled LGBTQI Lagos, queer Nigerians in the capital city are photographed through a refreshingly empowering lens. Mostly shot at home, in his subject’s most comfortable spaces — bedrooms, passageways and balconies — Adedamola doesn’t sensationalise any of their stories. Save for the odd party scene, these simple, domestic settings he finds his subjects in rebel against conventional notions of queer imagery.

Adedamola’s signature style is to shoot in black-and-white, which he explains gives a better focus to his subjects and takes away any distractions. Without context, this collection of images could easily pass for something beautiful and deceptively simple. But knowing their whole story — of these young queer Nigerians standing defiantly in the face of oppression and persecution — imbues the story with a far more affecting power.

In Nigeria, homophobia has been written into law since 2014 through the Same-Sex Prohibition Act. The act prescribes jail sentences of up to 14 years for anyone who participates in an open display of affection for someone of the same sex, sets up an association or gathering to foster a community of LGBTQ+ Nigerians, or attempts to marry someone of the same sex, among many other prohibitions. While no convictions have yet been made under the law (according to Reuters late last year), it has increased hostility towards communities and cohabiting partners. Before the bill passed, some were happy to look the other way.

This discrimination also trickles into the media and defines what type of content is produced, what kind of faces and stories are permitted on-screen, and what narratives are given credence. This is why queer folks in Nigeria benefit from having their stories told with nuance, objectivity, and a substantial dose of humanity.

“The importance of this project really hit me during the #Endsars protests, when queer Nigerians were asking for the same rights as everyone else,” Adedamola says. “Queer Nigerians were simply highlighting their struggle only to be met with violence, forceful erasure, and told to wait for another time to fight for their rights. But things are not done that way, there might never be a right time, and so I knew I had to take this project seriously and combat the increasing level of erasure.”

For Onyx Godwin, a subject in the LGBTQI+ Lagos project, dressed in drag and captured while sitting regally on a plush wide-armed chair in one picture and touching up his makeup in the bathroom in another, visibility is vital. Not just for combating the hateful narrative about queer Nigerians that non-queer Nigerians are fed by the press, religious bodies, and the government, but for young queer Nigerians to be equipped with empowering and positive stories about their own identity.

“The more we are seen, the more people understand what is happening with us, and if I can do something to make sure we are seen in a different light from what is the norm, I want to be a part of it,” Onyx says.

Ethan Regal, another subject of Adedamola’s project, photographed in his home, sitting on a couch with a quiet, thoughtful expression on his face, hopes that this project will be a helpful guide for queer folks. He wants Nigerians struggling with their sexuality, unable to find other people like themselves, to know a community is out there. “We need to get more stories out,” he says. “It is important that people see that, amidst all the chaos, queer Nigerians are still able to find ways to thrive and be there for each other.”

With the project still ongoing, Adedamola is hoping to photograph a few more queer faces of varying sexual identities and gender expressions, and continue to do his part in documenting these vital stories. “The fact that queer people are invisible makes it feel as though they don’t exist,” he adds, “and this is why this project exists.”

Credits

All images courtesy Adedamola Odetara