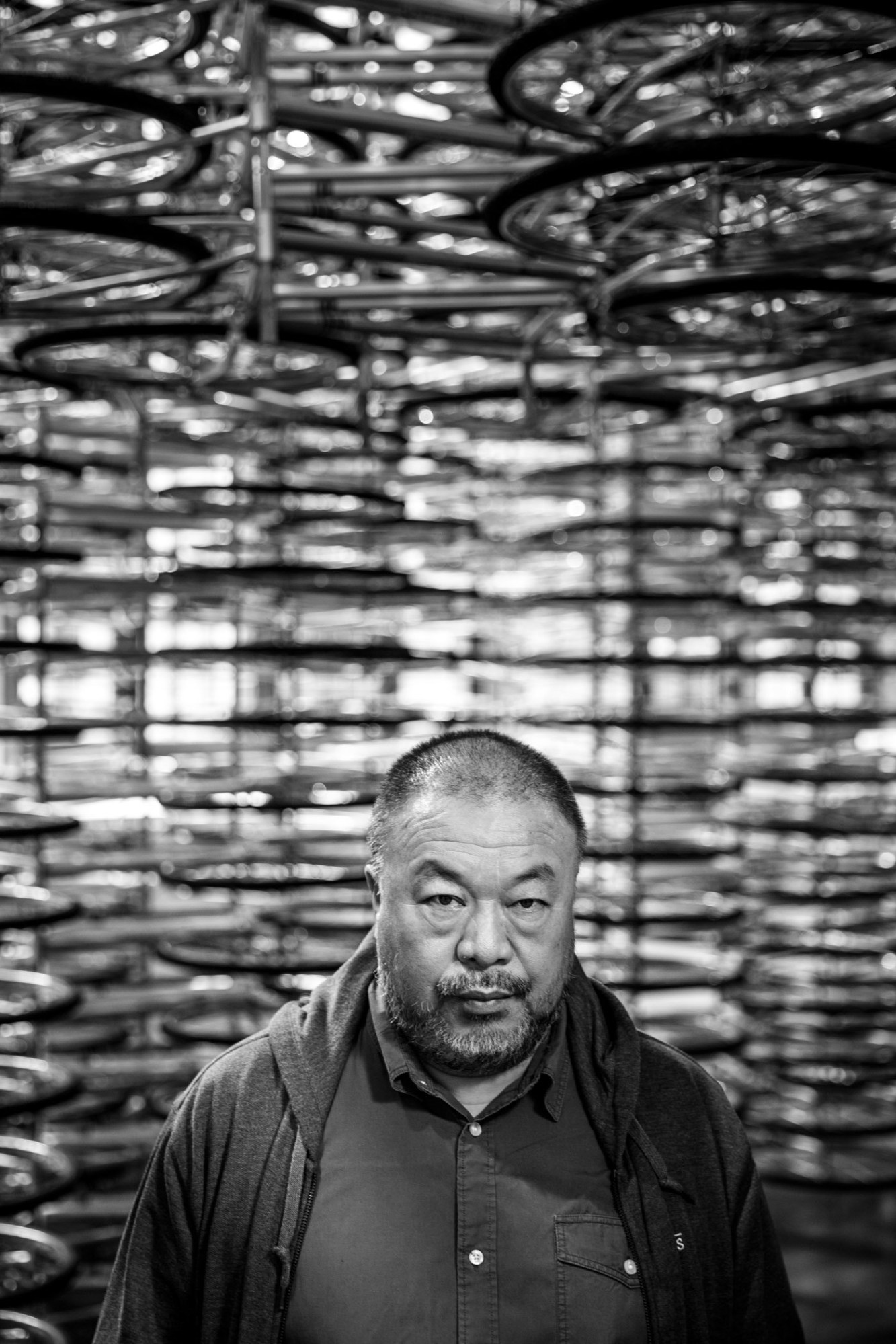

It seems very en vogue in the art world to express a distaste for a contemporary artist like Ai Weiwei. Is he feted for the context of his life, instead of his work? If the refugee crisis ever ends, will anyone remember the red PVC lifeboats hanging at the facade of Ai Weiwei’s new retrospective in Florence? What longevity does a portrait made of lego have? Or the artist photographing himself swearing at The White House? How does one go about exhibiting a massive stack of bicycles, and does anyone even care?

Because Ai Weiwei is as known for his political and social activism as he is for his contribution to contemporary art, his art often lies beyond the realm of art to satisfy the art critic. His practice places debate, conversation and the raising of public consciousness at its center; more often than not sacrificing subtlety and beauty for obviousness and protest.

The artist is not necessarily concerned with art itself, but is more focused on its possibility to transmit a message. “I don’t like any of them,” he told i-D, when asked about which of his works he was most pleased with. “It’s not about the work, it’s about saying something.” And that’s exactly what his new, and most in depth, retrospective to date is all about.

Titled Libero, it’s just opened at the historic Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. As part of the retrospective Ai unveiled a new work, Reframe. The latest in a series of works he’s devoted to the refugee crisis, Reframe consists of a series of over 20 red lifeboats hanging from the untouched facade of the Renaissance Palace in the center of Florence.

“I’m very keen to look at the ways in which humans have lost their lives because of different situations,” the artist explained. “I think to have a show in one of the most important art museums I needed to make a statement. I think that art, especially contemporary art, is about raising the consciousness of people. So I am very happy that in Italy the work has lead to discussion in relation to current issues, which is most important. I really do care about the situation also.”

Like much of Ai’s work on the refugee crisis, Reframe has sparked debate intense debate: there have been protests by the far right in the streets of Florence and the press have slammed the work as distasteful and sensationalist. One certainty is that these lifeboats are impossible to ignore, which is exactly the point.

“I have a strong respect for everyone who is fighting for freedom, willing to sacrifice everything, take a risk, take their children for a better future,” Ai Weiwei explained as part of the motivation for these series of works on the refugee crisis. “Those people are the heroes of our time. I have full respect for them. My work is about showing my clear respect for those people and their fight for freedom. They have been called many very bad names, but they are our brothers.”

It is also something deeply personal to Ai too, of course. As on April 3rd, 2011 he was arrested, held in a secret location for 81 days, and interrogated over 50 times because of his criticism of the Chinese state; an essential theme that punctuates the artist’s entire archive. His work Snake Bag was created after approximately 70,000 people lost their lives in 2008 during an earthquake in Sichuan. Snakebag criticizes the corruption of Chinese authorities for their negligence in providing stable structures which would be able to survive such a disaster. Thousands of children died in the earthquake when their schools collapsed. Ai turned typical school rucksacks into a memorial for them, as the Chinese government refused to acknowledge their deaths.

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn is another series of portraits that grapples with Chinese society, remade here in Lego from an earlier photographic work by Ai, that depicted the artist dropping and smashing a 2000 year-old urn. The work represents the artist’s personal feeling of discordance with at once belonging to and fighting against Chinese tradition and state. It sums up Ai’s unique position in the art world via his relationship to Chinese culture and history, and how that has turned into a radical political and artistic output, often using simple, powerful gestures to undermine state hegemony.

Were a British artist to produce the same works as Ai Weiwei, they would—and should—be received with much less clout. As someone who is fighting against censorship, a surveillance state, and is under constant threat of arrest and legal punishment, Ai Weiwei’s work is so much about the system against which he is fighting. Every gesture and act takes on a magnified importance.

Nearly every work shown, and produced by the artist, is in some way responding to changing socio-political climates at the time of their making. The artist often comes under criticism for lacking a thorough theme or a style which is markedly ‘Ai Weiwei’, but who really cares? The mission statement of the artist himself is to ask questions, be politically active, and challenge inequality on an individual, as well as global, scale: something which he undertakes with great skill and simplicity. He is taking art out of the hands of the art world, and providing accessible, expositive stimuli in order to open up debate, and open up people’s eyes and mouths.

“Even though there is so much uncertainty, it is a time of political change,” he continues. “There are strong conflicts: not only on the front line, and within governments, but in our hearts and in our minds. As a human we always have to question what we think today. And it’s something we can give to others too. We are still not at a time that we are so privileged we can forget about other people and their existence. For example, I still have not met anyone who was not a migrant at some time in their history. So in this time there is only one value we have to defend — and that’s humanity. Otherwise we are divided: religions, geographies — we are separated into many different things. But it’s humanity, as human, as individual, as every citizen, we have to defend.”

Ai Weiwei is an activist before he’s an artist. One of the lead images in his Study of Perspective series of works is a picture of him sticking his middle finger up at the Palazzo Strozzi, replicating the gesture in front of over 40 other institutions and tourists from the Tate to the White House to the Eiffel Tower. Again, it’s a simple, uncomplicated, hugely effective gesture. He is refreshingly un-art in this respect, in that his work demystifies both the world of the gallery and the political situations his artworks are discussing. His retrospective may not be filled with objects of timeless beauty, but it is packed with 30 years of political and personal struggle, which is something much more universal than beauty.

Credits

Text Tom Rasmussen

Exhibition photography Alessandro Moggi