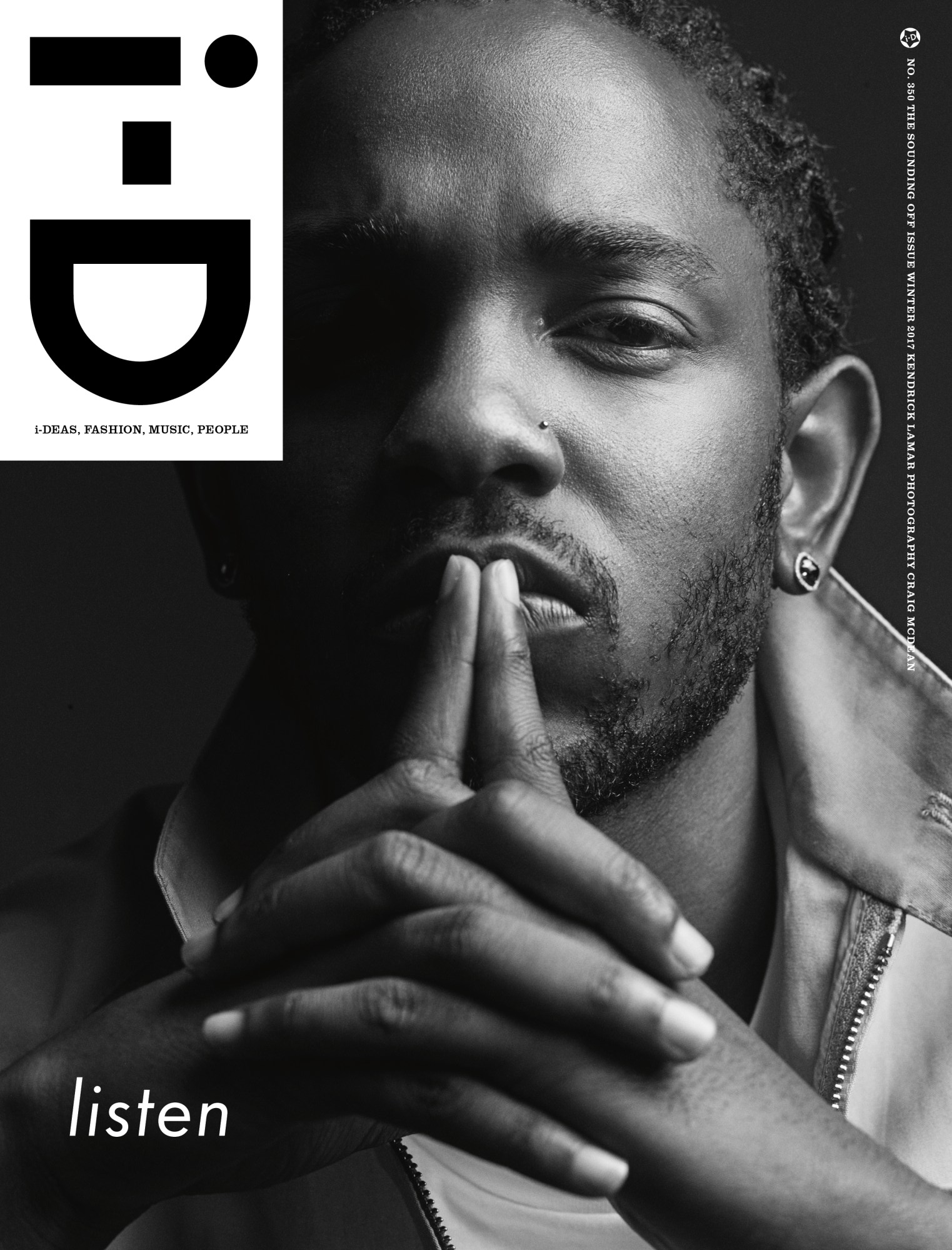

This article originally appeared in The Sounding Off Issue, no. 350, Winter 2017.

“I… don’t… know,” Kendrick Lamar says when asked to explain why Donald Trump became President of the United States. Few people understand America the way Kendrick does, so surely he must know something about how the billionaire reality TV star has happened to his country. He’s sitting in a little dark gray room backstage at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, New York, on a Sunday afternoon. It’s just a few hours before his show. He’s in silver Nike Air Max and a maroon sweatsuit, top and bottom, with the TDE logo. That’s Top Dawg Entertainment, Lamar’s label. He’s calm and softly spoken and radiates intensity because his words are well chosen and carry weight. Kendrick isn’t voluble but he is deep. He’s perceptive, wise and quite often brilliant, so like many Americans, when it comes to Trump he’s still in shock. “We all are baffled,” he says. “It is something that completely disregards our moral compass.” The shift is almost tangible for Kendrick because Obama is not just a President he respected and admired, he’s also a friend who loves his music and invited him to the White House.

“I was talking to Obama,” he says, “and the craziest thing he said was, ‘Wow, how did we both get here?’ Blew my mind away. I mean, it’s just a surreal moment when you have two black individuals, knowledgeable individuals, but who also come from these backgrounds where they say we’ll never touch ground inside these floors.” A pause. He briefly recalls his grandmother, who died when Kendrick was a teenager; how incredible might she have found this, a black man in office, talking to her grandson. “That’s what blows me up. Being in there and talking to him and seeing the type of intelligence that he has and the influence that he has, not only on me, but on my community. It just always takes me back to the idea of how far we have come along with this idea about how [much] further we can go. Just him being in office sparks the idea that us as a people, we can do anything that we want to do. And we have smarts and the brains and the intelligence to do it.”

Both Barack and Kendrick came from nothing and ascended to legendary status on the strength of their words and their gifts for oration. They sat and talked in the Oval Office about the improbability of their lives – how did we both get here? And now, as far as the White House is concerned, both are all but considered enemies of the state. “It’s a complete mindfuck,” Lamar says of going from visiting the White House to feeling hated by it.

“The key differences [between Obama and Trump] are morals, dignity, principles, common sense,” he says. Where Obama was an inspiration, it’s hard for him to even respect Trump. “How can you follow someone who doesn’t know how to approach someone or speak to them kindly and with compassion and sensitivity?” But ultimately the rise of Trump has brought out something new in Kendrick. “It’s just building up the fire in me. It builds the fire for me to keep pushing as hard as I want to push.”

The fire inside must be blazing right now because Kendrick’s newest release, Damn, his fourth studio album, is both a commercial and a critical smash. It’s sold over two million copies and has every review writer struggling to outdo the praise showered by all those who superpraised Kendrick before them. Pitchfork’s review calls Damn, “a widescreen masterpiece of rap, full of expensive beats, furious rhymes, and peerless storytelling about Kendrick’s destiny in America.” Lamar’s vision for Damn meant asking his producers, “‘What can we do to make it live in another space and be ourselves, but also challenge ourselves?’ As far as the sonics of the album, we wanted to make it where it was really back to the future, something you’ve never heard before, but something you’ve heard before. If that makes sense.” At this point the hip-hop universe seems to be unanimous in its belief that the greatest MC in the world right now is Kendrick Lamar. He could win a battle against most underground MCs and he could outsell most pop rappers. He is the undisputed current king of hip-hop.

Kendrick lives a life that befits the king of hip-hop, if you think what truly befits the king of hip-hop is to basically live in the studio looking for the perfect beat and the ultimate rhyme. “I can sometimes cut the whole world off to write a verse that is perfect to me,” he says. “I could be in the studio all day and turn the phone off and completely zone out, because I feel like this was what I was chosen to do. And I can’t let anyone get in between that.” Unlike many MCs, when Kendrick creates, he’s not high. “I want to make the music in the most sober mind as possible, that way I know it’s me making it, not just the liquor!” If hip-hop is a game, Kendrick wants to win. “Hip-hop plays two ways in my head. It plays as a contact sport, and also as something that you connect to – songwriting. Growing up and listening to battles between Nas and Jay-Z, that’s the sport for me. That’s where it can get funky, that’s where I can say whatever I want, however I want, whenever I want. Then there’s the other side, which is showing something that people can actually relate to, and connect with. I have that competitive nature, and I also have the compassion to talk about something that’s real.”

“Hip-hop plays two ways in my head. It plays as a contact sport, and also as something that you connect to – songwriting. Growing up and listening to battles between Nas and Jay-Z, that’s the sport for me.”

Asked if he’s written the perfect rhyme yet, Kendrick decides the album’s 12th song, Fear, contains the best verses he’s ever written. “It’s completely honest,” he says. “The first verse is everything that I feared from the time that I was seven years old. The second verse I was 17, in the third it’s everything I feared when I was 27. These verses are completely honest.” He got to that honesty through years of work with a studio family that helped keep the king humble. “Everything you write is not dope,” he says. “Even if you’re a great writer, a bunch of the stuff you write is wack. But most people don’t have somebody around to be like, ‘That’s wack.'” Kendrick has friends who are empowered to tell him what’s not working and he says that has made a huge difference. “I’ve been in that studio writing terrible verses, writing terrible hooks, with homeboys and friends and people that you trust telling you, ‘That’s garbage.’ I grew thick skin and got back in there and did it all over again. And then you eventually grow an ability to know when something is too far. I learnt how to challenge myself to take it to the next level.”

But for Kendrick to reach his throne he’s had to do much more than learn how to rhyme. He grew up in Compton, California, a rough place that has sucked up many souls, a place where gangs, killers and dead bodies littered Rosecrans Avenue, where he lived until relatively recently. Music wasn’t just an outlet, he needed it to save his spirit. He grew up obsessed with Snoop, Dre, Pac, Public Enemy, KRS-One, Rakim, Jay-Z and Kanye, as well as Michael Jackson, Quincy Jones, Prince, Marvin Gaye, the Isley Brothers, Luther Vandross and also Malcolm X. “His ideas rooted my approach to music,” he says. Reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X as a teenager contributed to shaping Kendrick as an artist. “That was the first idea that inspired how I was going to approach my music. From the simple idea of wanting to better myself by being in this mind-state, [the] same way Malcolm was.” Without music to give him purpose, he might have grown lost. “We used to have these successful people come around and tell us what’s good and what’s bad in the world, but from our perspective it didn’t mean shit to us, because you’re telling us all these positive things but when we walk outside and see somebody’s head get blown off, whatever you just said went out the window. And it just chips away at the confidence. It makes you feel belittled in the world. The more violence you’re exposed to as a kid, the more it chips away at you. For the most part, the kids that I was around, it broke them. It broke them to say, ‘Fuck everything, I’m gonna do what I’m gonna do to survive.'” How did he escape falling into that? “Before I let it chip away at me 100%, I was making my transition into music.”

Later that night, at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center, Lamar comes up from under the floor to a screaming, sold out crowd. He’s wearing a yellow tracksuit with black trim, recalling Bruce Lee in Game of Death, and he commands the stage, working alone for most of the show and dominating the arena. His small body exudes power as he moves about the stage. Like Rakim and Nas before him, he doesn’t dance and he’s as serious as a heart attack. The crowd can’t take their eyes off of him. In between songs, Lamar is on the big screen in clips from The Legend of Kung Fu Kenny, a little film he made, inspired by 70s kung fu flicks. In it Lamar gets to look like he’s in a kung fu movie, but this is not costume play, it gets at the core of who he is. In those movies there was often an obsession with acquiring skill and showing off mastery and an internal battle to excel. That’s who Kendrick is as an artist – he’s focused on polishing his skills and displaying his mastery and pushing himself to greatness. Asked about his favourite words, besides “perspective” Lamar says, “discipline.” “I love that word,” he says, “because it shows who you really are. There are so many vices in the world, especially being in the entertainment business. You’re exposed to so much at any given time. Whatever you need is right there in your face. But how much discipline do you have when the camera’s off, when the light’s off? That inspires me. How to restrain that. And that shows who you really are. To control yourself, that is the ultimate power.”

Kendrick is learning more and more about how to control himself, partly through daily meditation sessions each morning. “I need 30 minutes a day of just reflecting on the moment,” he says. “When you’re in this business, everything is,” he snaps his fingers. “Years go by so quick, because you’re working and you’re also planning for more work within the next six months to a year. So for me, I just have to sit down and reflect on what’s going on in these 30 minutes.” His meditation practice helps him gain perspective, which he says is his, “number one favourite word”.

“I’m a human being, I’m a person, I have family, I have my own personal problems. But I have to give to the world. That’s my responsibility. It’s not just a job or entertainment for me; this is what I have to offer to the world.”

But he still lives in Trump’s America, where racism is becoming more overt, more prevalent and more violent. Some in the resistance have adopted To Pimp A Butterfly’s Alright as an anthem and he knows the power that song has. “I’d say that’s one of my greatest records because it gave these kids an actual voice and an actual practice to go out there and make a difference. They’re going out and they’re walking the walk and talking the talk whether it’s inside their communities, whether it’s inside their juvenile systems. They wanna make change.” Is there a sense of accountability in some way; does Kendrick carry the weight of the community on his shoulders? “It’s definitely a responsibility,” he acknowledges. “I’m still a human being, I’m still a person, I still have family, I still have my own personal problems. But I have to give to the world. I think that’s my responsibility, [to learn] from my mistakes [and to spread] the knowledge that I have, the wisdom that I have. It’s not just a job or entertainment for me, this is what I have to offer to the world.”

As well as his impact on global pop culture, Kendrick’s local community is also benefitting from his success; he has helped dozens of his peers find jobs that aren’t just “making money” but “earning a living”. “You put YMCAs inside your community and you give a job to these cats that can’t be hired anywhere else. You make the opportunities, and that’s what I’m doing personally. Because once I put the power in their hands, they can put it in the next, and they can put it in the next. People can’t believe that it can change that way. But it has to start with one.” Dr. Dre and Venus and Serena Williams are also active in the city of Compton, while its female mayor, 35-year-old Aja Brown, is effecting real change. “This generation has opportunities that my generation didn’t have,” he notes, adding that to be present in these communities holds true power. It’s not enough to merely donate or write powerful songs or tweet messages of positivity; you must show and prove. “There’s a lot of people that are scared of their own people, the gang culture that is still there, but you can’t be scared. You gotta be there, because it shows confidence not only in yourself but in those in the neighbourhood. People want a reason to hate you. Don’t give them that reason. What’s going on now is that transformation of us not being scared of where we come from. And that idea is gonna get passed on.”

Lots of people want change but how does true structural revolution happen? Is Alright just a song or is there something more behind it? Lamar promises that we gonna be alright, but how? How do we get to actually being alright in such a crazy nation? “I always go back to the community,” Lamar says. “Simple as that. Because I see these kids growing up without a father and they don’t have this confidence of knowing that they’re better than the environment that they’re in. So getting to alright is just installing confidence in them. To let them know that I come from where you come from, and you can ultimately make a change.” Kendrick Lamar knows that he is an artist who has the power to change the world and he’s working on trying to do just that. “When I’m gone,” he says, “I can rest peacefully knowing that I contributed to the evolution of this right here, the mind.”

Credits

Text Touré

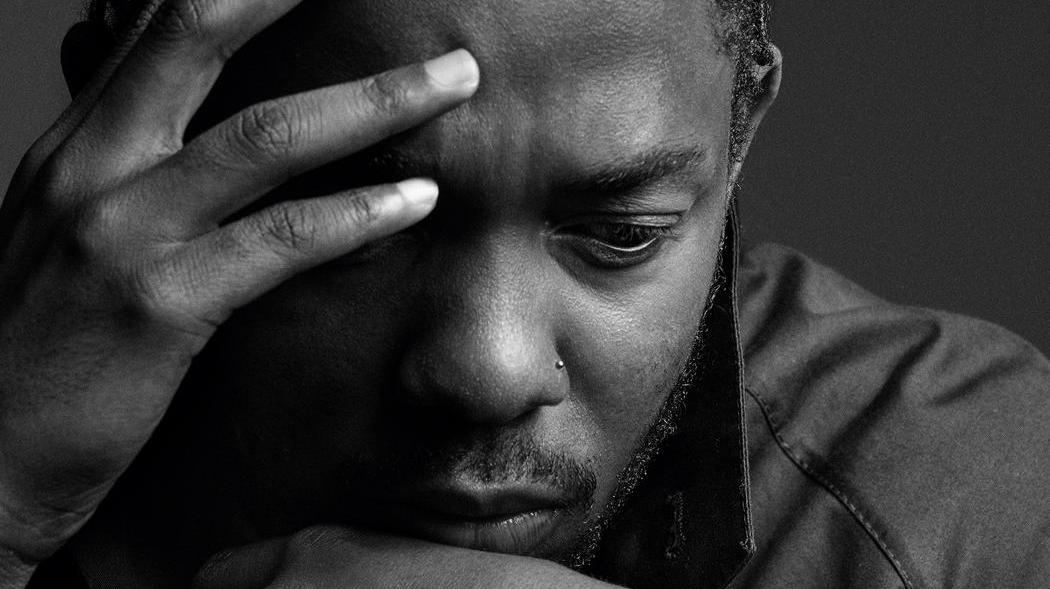

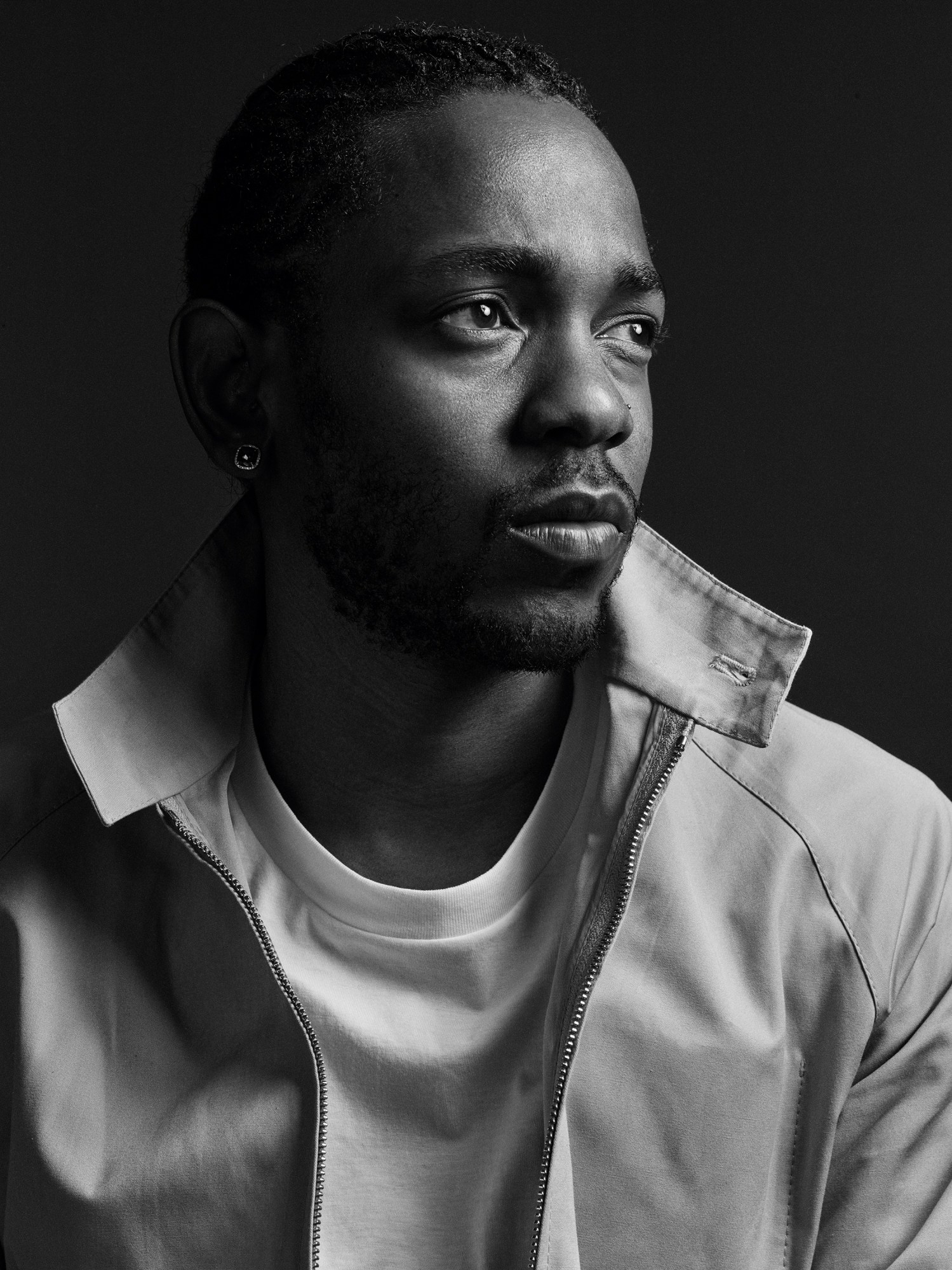

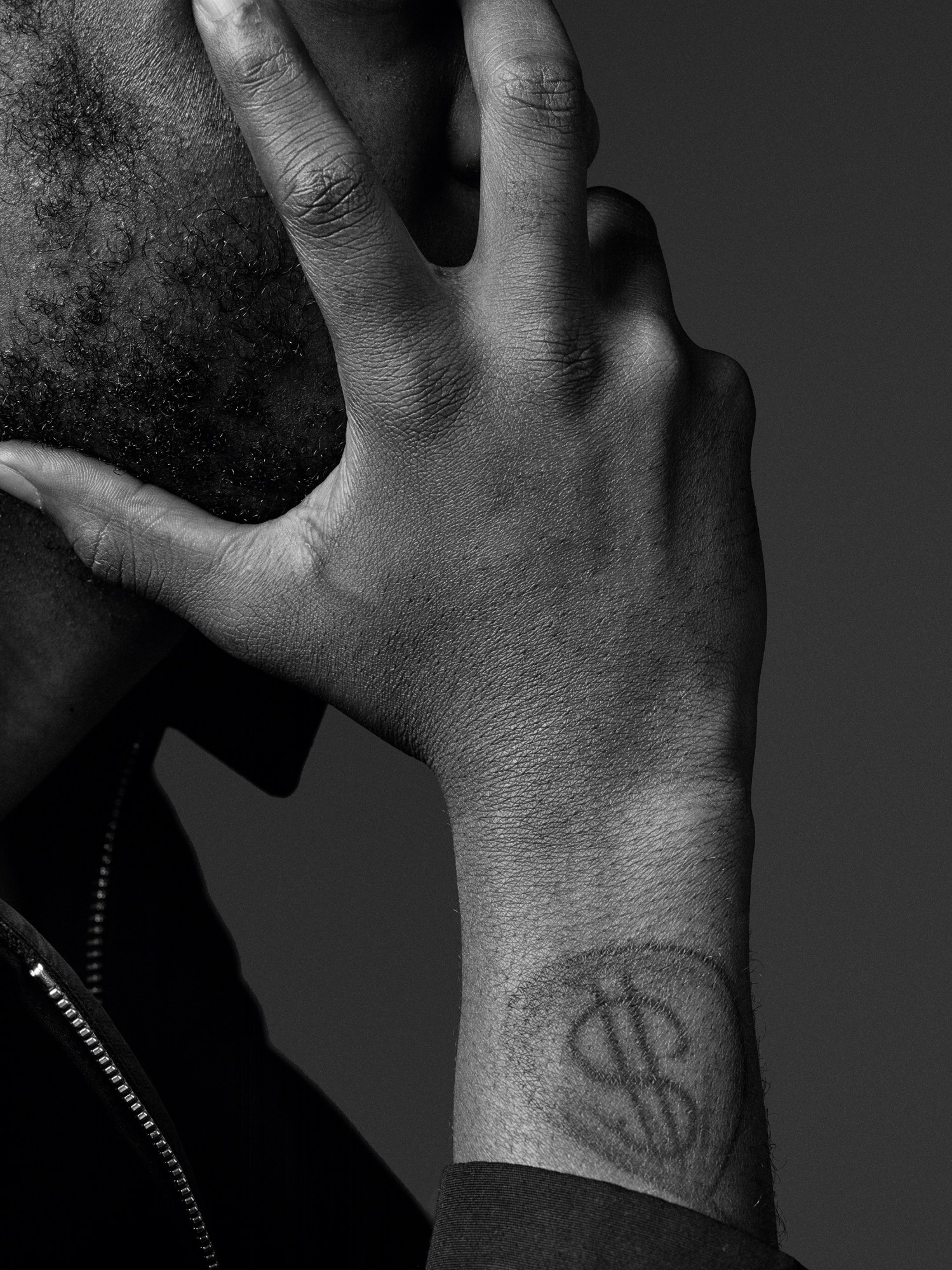

Photography Craig McDean

Fashion Director Alastair McKimm

Grooming Francelle Daly at Art and Commerce. Photography assistance Nick Brinley and Maru Teppei. Digital technician Nick Ong. Styling assistance Sydney Rose Thomas and Madeleine Jones. Grooming assistance Ryo Yamazaki. Production Gracey Connelly and Dyonne Wasserman.

Kendrick wears all clothing Prada.