The Prodigy gatecrashed the charts with the cheesy, chirpy rave anthem Charly. Then came a string of hit singles, a best-selling album and a Mercury Music Prize nomination. But, believe it or not, what these Essex lads really want to do is put hardcore’s adrenalin thrill into stadium rock.

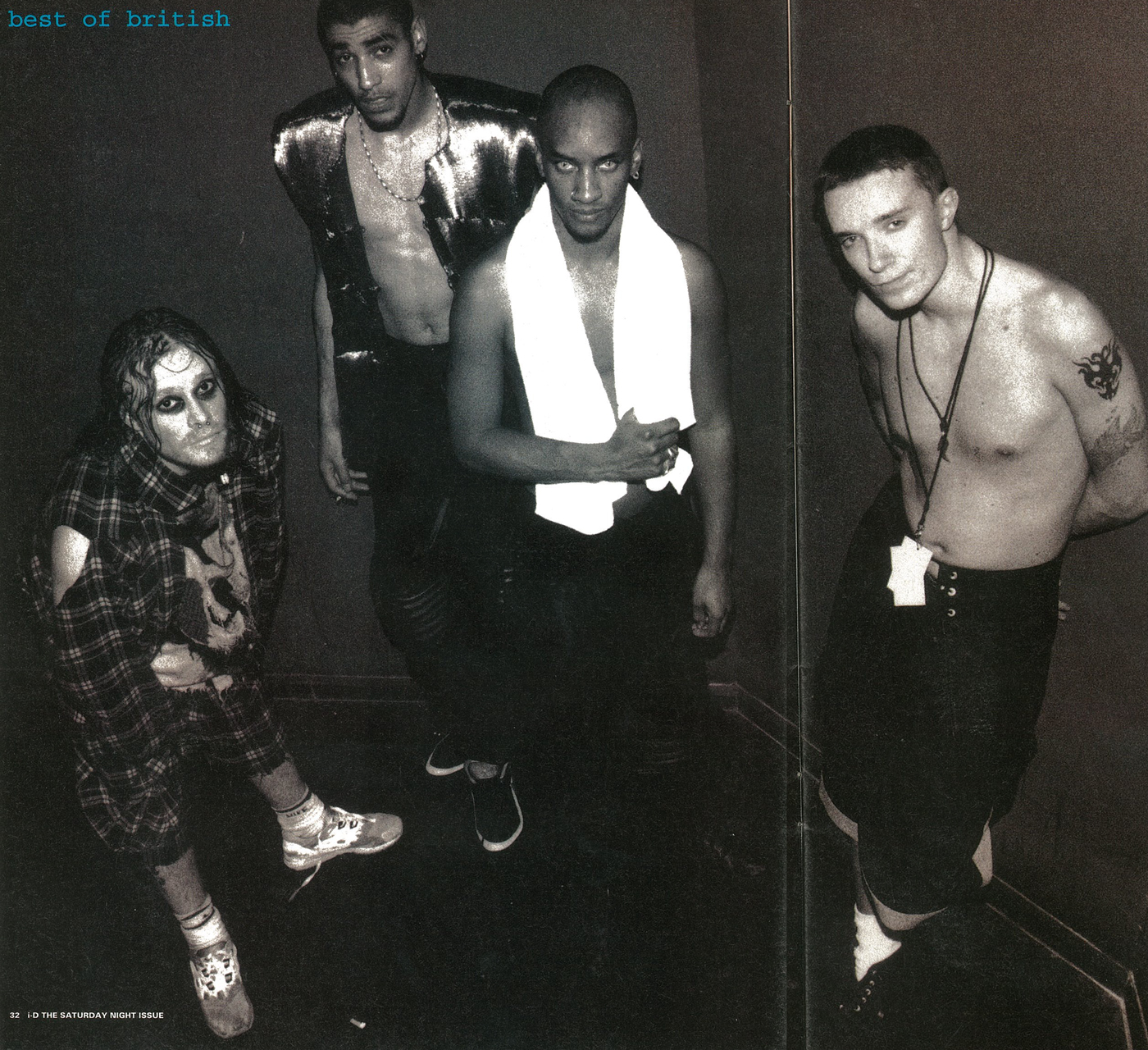

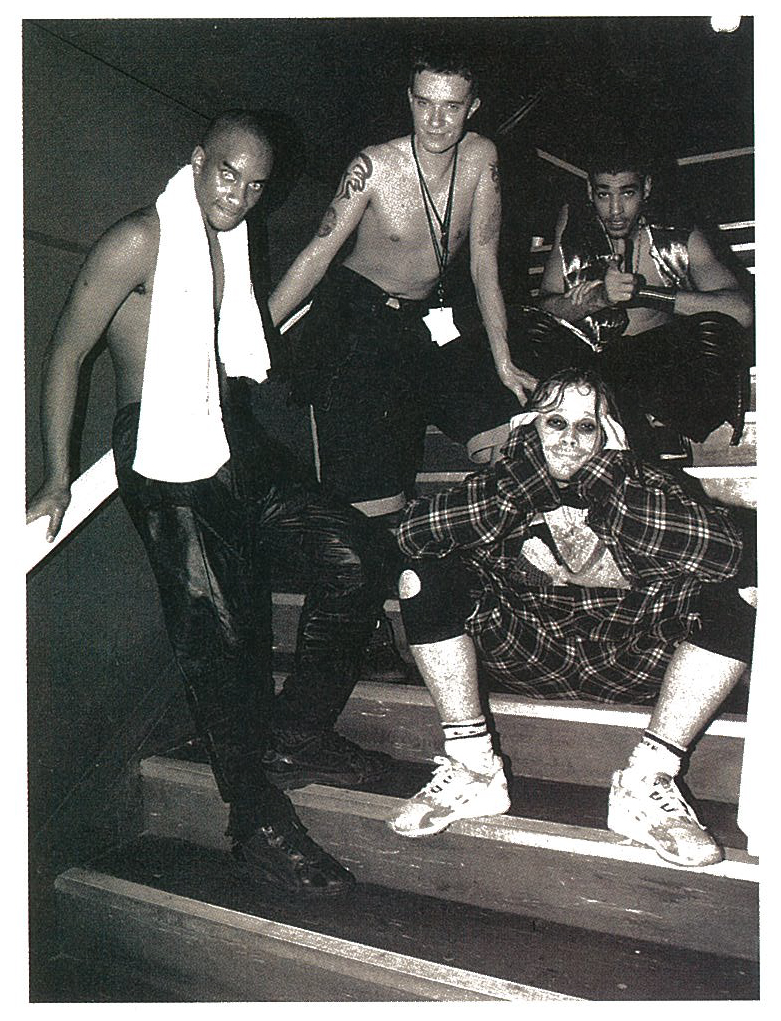

Keith Flint is limbering up. His heavy-lidded eyes roll in a huge head that strangely recalls Brian Jones reincarnated as a raver. He pulls on a tartan shirt, ripped, stitched and patched to hell. He rummages for a tartan jacket, baggy at the shoulders and tight at the waist. With his distressed knee-length shorts, he looks like a Dickensian nutter who’s stepped into Westwood circa ’84. He loops a heavy black belt three times around his neck. Fingers the three-day-old septum gleaming from his nose. Playfully jostles Maxim Reality aka Keety aka Keith Palmer away from the mirror. Applies black eyeliner. Keety’s piratical frock-coat skirls as he turns round. He’s got the tiger pupil contacts in, the ones that burn brightly in the night, make him feel evil, capable of anything. Avoiding Leeroy Thornhill, he starts to stretch. Leeroy jogs lightly on the spot. His baggy, black pants are weighted with monstrous corrugated bumpers at the knee. They flap around his thin legs as he starts in on some press-ups.

“If I came off stage and felt like a good hard shag then it wouldn’t have been a good show,” says Keith.

Dom, DJ Physics, sits, phlegmatic, giving nothing away. Richard, the guitarist drafted in, paces backwards and forwards. It is the first night of The Prodigy’s Jilted Generation Tour in Blackpool, and he’s not sure how his playing will mesh with Liam’s songs. Far from the cramped chaos of the dressing room sits Liam. He’s withdrawn, subdued. For someone who’s had a string of classic singles, an excellent 1991 debut album, Experience, a number one album earlier this year, Music For The Jilted Generation, and a Mercury Prize Nomination, he’s remarkably down to earth. His tattoos, two on each forearm, some Celtic-inspired, another derived from The Orb’s Pomme Fritz logo, have disappeared underneath a baggy brown top. He frowns and picks up his perspex box of discs. He counts them carefully. He counts them again. He counts them a third time. He shuts the lid. Gets up. Touches Keety on the arm, smiles at him, sweeps all the Prodigy dancers up with him as he negotiates the crowded silence of the room, the gear, the boxes, the beer cans, the strewn clothes. Security square their boxy shoulders. Someone opens the door and the refrigerator hum of the nightclub crowd leaps in like a caged animal. It sprays The Prodigy with electric spittle, visibly jolts them. They’re ready.

“My life could fall apart, but when I’m on stage it doesn’t matter.” Keith is slumped on a bench thick with bags and bottles. He drawls like Jools Holland. “If I came off stage and felt like a good hard shag then it wouldn’t have been a good show.” He grins. “I used to throw up every few shows just from the energy of the whole thing.” For the last hour-and-a-half, Liam’s sonic-heavy weather has been smacking him in his stomach, pushing him to his knees. Leeroy and Keety locked him in a fibreglass box large enough to hold a monkey. They laughed as he contorted into a painful rictus. No wonder the last track of their Experience album is called Death Of The Prodigy Dancers. “It’s a license to do anything really,” he muses. “If you keep falling over in a club people wouldn’t have it, but on a stage it’s alright for some reason. You know when you’re young, you’re experiencing things for the first time. You’ve bought The Jam or Gary Numan. You’re playing Going Underground. You’ve got it going flat out and you just wanna hit things.” He thumps the bench emphatically. “The floor’s shaking and your old man’s calling. It’s like that buzz. A tune comes on and I just want everybody to know that I love this. You just want everybody in on the buzz.”

The Prodigy dancers don’t dance so much as they stagger, ripped, torn apart by the ferocious kick-stabs, the evil coils of Belgian bass that snake and loop out of Liam’s synths. They keep on freezing and staring at each other in a daze as if the music is stunning them into stasis. Sometimes it sounds industrial, proto-gabber really, with stroboscopic slabs of noise juddering across the mix. Then Keith headbangs while Maxim prowls the stage. Poison is his lullaby. The refrain, “I’ve got the poison, I’ve got the remedy”, is the dare he offers the crowd, the choice he lures them with.

On stage, Liam whiplashes his friends. Off stage, they protect him. They’re older — Keith and Leeroy, 25, Maxim, 27, while Liam’s just 22. He changes back into his usual clothes, a Jilted Generation T-shirt, skate pants, Oakley shades snug against close-cropped hair. A silver armband and silver rings on each hand slice the air. The Prodigy downloads his thoughts, often doubling back, eager, even anxious to get them precise. “We’re a hard dance band doing hard dance music now. In a way I am a soloist because the music’s my thing, but without the others to back me up The Prodigy wouldn’t exist.” He reaches for a parallel. “If you go and see Pearl Jam, they just stand there but The Beastie Boys, they give you a show. They’ve got energy and that’s what we’ve got. I wouldn’t even say we’re a rave group anymore because there is no rave scene anymore, is there? It’s all fragmented, split up into different scenes.” It’s not a scenario that bothers him much. “I feel more at home in the indie scene, you know. Bands like Senser, Rage Against The Machine, that’s who we like.”

“Senser are wicked,” Keith, who’s wearing a Helmet T-shirt, emphasises. The others agree. “Street music, that’s what we’re about,” Liam insists and his determination sends me back, back to a South London warehouse in the summer of 1991. The Prodigy are laughing and joking on a darkened video set. They are rehearsing their first-ever video, and they are doubled up with the excitement of it all. From a balcony far above, we can see Liam, a tiny figure with a pageboy bob. His face is streaked with the orange whiskers of a projected cartoon cat called Charly. “Playback!” someone yells, and that yawning, yowling, feline squeak fast-forwards again. It hurls The Prodigy around the set like they’re back at school. Surrounded by a gaggle of friends from Braintree in Essex, they’re all dressed in one-piece suits like they’re at the circus or the fair.

That sample, “always tell your kids before they go outside”, takes hold and they all hold on as if it’s the very apex of the rollercoaster. We must have heard 2,027 times that day and when we stepped out, dizzy, giddy, the dance world as we knew it had changed forever. Charly instigated a generation gap like no other record. To an ’88 generation intent on building a ‘mature’ British house industry, Charly was an outrageous regression. The Americans must be laughing at us! For the rave youth of ’91, Charly was an anthem.

American pop culture was about to make the same move Liam had, turning back to The Brady Bunch and The Partridge Family, accessing a moment of shared TV culture just as Charly had. By tapping into a memory everyone could not but dimly, helplessly, recall, Liam had scrolled back to pre-adolescence, to the years before taste formation and peer pressure, when we were all plugged indiscriminately into the maternal TV screen. Dancing to Charly was like dissolving past hip, all the way back to the informational flux of pre-identity. The French psychoanalyst Lacan would say that Charly was an aural equivalent of the mirror stage and the aggression, embarrassment and shame the record unleashed suggests he wouldn’t be far wrong.

“I was as shocked as anyone else when Charly took off the way it did,” says Liam now. It’s part of his adolescence, and he’d rather talk about something else. “It was never meant to be a chart record. I remember when that Roobarb And Custard record came out,” he recalls disgustedly. “One of the guys who made it came up to me and said ‘We’re making money just like you did’. I thought, ‘what a wanker’. I didn’t make Charly to make money. I did it because I wanted to.” As if making money or having chart singles is so dreadful. Because he’s made so many successful records, Liam despises the charts. Scornful of Eurotrash pop, he yearns for ‘credibility’ and ‘seriousness’.

You could argue that the toytown virus Charly spawned is reactively responsible for the drive towards ‘intelligence’ and ‘progression’ that unites todays house, techno, jungle and ambient despite their differences. No one has escaped this fear of adolescence. Not Shaft, who made Roobarb And Custard and are now the serious Reload. And not Liam, who went straight from Charly to a trance remix of the Art Of Noise’s Instruments Of Darkness. And while hardcore reinvented itself as avant-garde jungle, Liam helplessly rolled out hit after brilliant hit. The split-second pop art of Everybody In The Place. The searing smash-and-grab of Fire. The classic astro-roots propulsion of Out Of Space. The manic groove lock of Wind It Up.

The singles haven’t stopped but Liam’s used the remixes to try out some hipster moves, calling on Jesus Jones, CJ Bolland and The Dust Brothers, all of which has pulled in music paper props. I suggest that The Prodigy needs neither the drone of CJ Bolland nor the music-for-students of The Dust Brothers. And as for Jesus Jones! Liam smiles but begs to differ. He’s remarkably unpretentious. He’d sink in an indie scene where boastful arrogance is the norm. “I wouldn’t say I’m shy, but I am reserved.” He takes a drink from the can of Coke an exhausted Keety has passed him. “When I meet new people, I really clock them. People are too trusting, I think. People who knew me at school think I’m a star, which is a load of bollocks really. None of us think we’re stars.” He eases back in an uncomfortable chair. “It took a good couple of weeks to sink in when I heard we were number one. Singles aren’t something I’m proud of. You just have to look at the charts and see what’s there. But albums…” He pauses, overwhelmed by the implications. “Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, big bands like that, they have albums. It means something.”

As for the Mercury Awards: “They’re a load of bollocks really. The actual award, I mean. What is it? It’s nothing. I never expected to win.” The Mercury Award wasn’t so much about dance fighting indie for the top pop stakes as it was about asserting the seriousness of albums over singles. In the Mercury universe, remixes and compilations don’t exist. Like books rather than magazines, it rewarded permanence and artistic expression. The Prodigy were there because rave is supposed to have grown up into ‘proper’ music you can listen to at home. A patronising attitude, yet it’s one Liam partly agrees with. “Experience sounds a bit dated now. Music For The Jilted Generation has a militant edge to it.” It is a real album, a concept double, with a gatefold sleeve and slow tracks with flutes (the excellent 3 Kilos) and guitars.

“I made Charly in my bedroom, but my dad was getting pissed off and I had to move out.”

“When I listen to a Nirvana album and hear a couple of slow tracks, it makes me feel better. You listen more closely, and that’s what I wanted. But people have gone over the top with this political thing. It’s not meant to be an album about the Criminal Justice Bill. I had the idea for the sleeve before all that happened. It’s just agreeing with the government really, saying you think we’ve all been corrupted by the dance scene and you’re right.” It’s Liam’s version of the college radio ‘alternative’ aesthetic he was exposed to while touring the States. “Over there, they’ll listen to Cypress Hill, The Prodigy and then a guitar group. It’s more open minded, like indie over here.” Certainly Jilted Generation is a heavier, more metallic record. Even though tracks have names like Speedway and Break And Enter, they’re actually less speedy than anything on Experience. This new ambition is signalled in The Narcotic Suite, a three-part exploration of altered states which ranges from hash fuelled ultraviolet breakbeats (3 Kilos) to stinging acid paranoia on Claustrophobic Skies.

Like Depeche Mode, another single-heavy synth pop band from Essex, The Prodigy are bound for stadium rock status. The group reject this analogy. Depeche Mode came from Basildon, “where they all act like they’re from London”. Braintree, conversely, is “more chill, more of a country town”. Maybe the ‘Jilted Generation’ refers more to growing up with a frustrated sense of marginality, of being compelled to invent a life because no-one else will hand you one. The edge cities and the satellite towns, the suburban bases of Hertford and Romford where everyone from Moving Shadow to Orbital seem to live: that’s where the action’s at these days. The four friends all met in The Barn in Braintree, raving to Renegade Soundwave and Meat Beat Manifesto, Genaside II and Silver Bullet. Keith had come back from Israel. Leeroy was counting time as an electrician. Liam was making tapes at home, doing layout for a free magazine called Metropolitan, designing rock T-shirts, trying to get on in hip-hop as Cut To Kill but getting nowhere.

Unlike Brit rap, hardcore had no rules, no inherited weight. “Me mum and dad split when I was 11 and I lived with both of them,” Liam recalls. “I’m closer to my sister really. When we got into rave I was living at my dad’s. I made Charly and the whole of Experience in my bedroom, but my dad was getting pissed off and I had to move out. He’s really proud of me, really follows the music and gets into the tracks. Me mum, she likes them but not so much…” The others are getting restless. The buzz is wearing down. Liam looks at his Storm watch with its metal case and two clocks. “Useful for snowboarding,” he grins, pulling down his Oakleys and looking around. After the rave comes rock, and with rock comes adrenalin sport — snowboarding, motorcross biking, skating; anything to keep the rush alive. And at the bottom of it, the biggest, most blazing rush of all: The Prodigy itself, the music, the energy, the devotion.