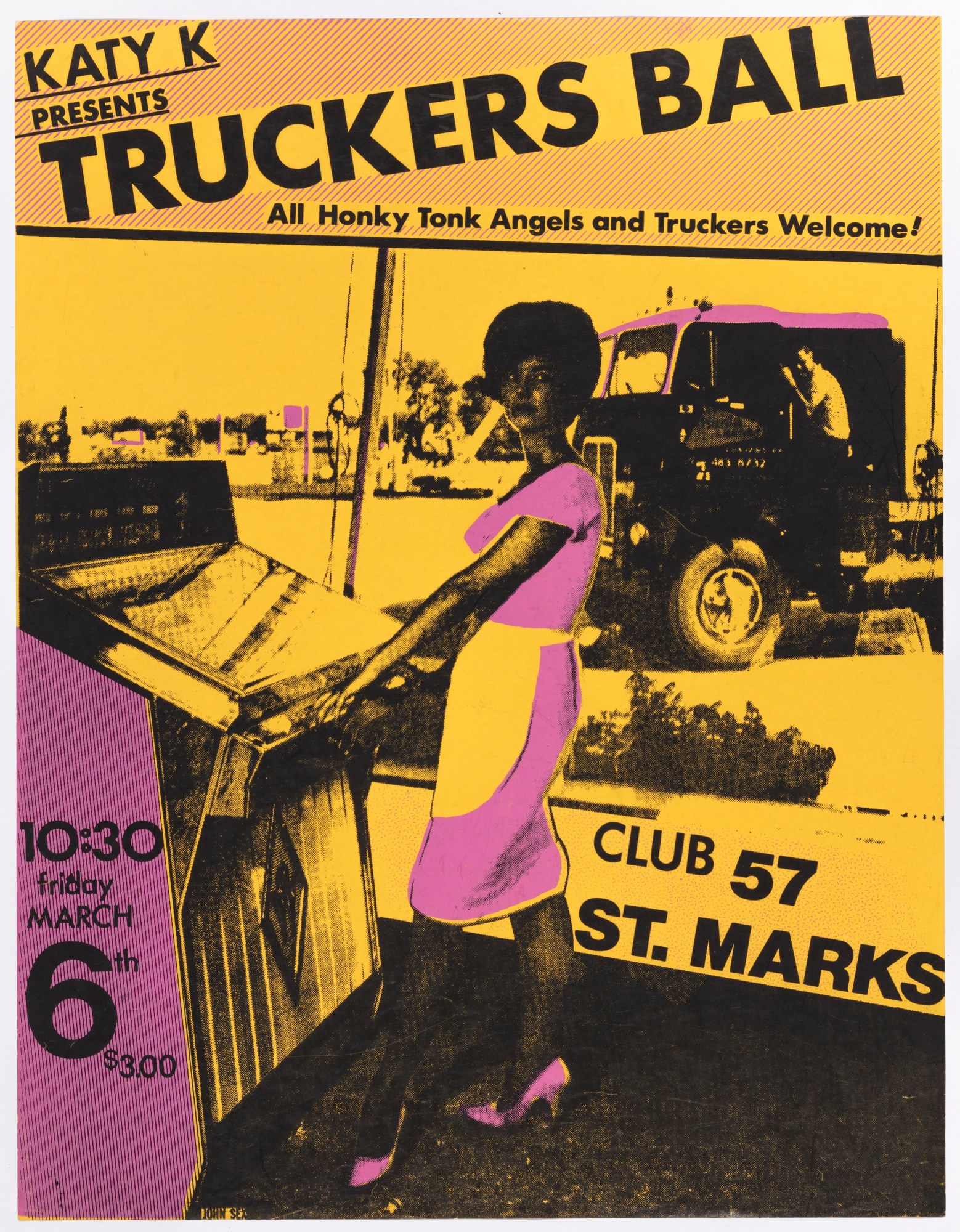

New York has, and will to continue to have, a revolving cast of “it” spots. Some standouts include Studio 54 (1977-1979), the four-floor Danceteria (1979-1986), and Pyramid Club (which is still open, but very different from its drag queen-beloved 80s incarnation). But only one space can take credit for nurturing Jean-Michel Basquiat, and for merging art and nightlife in the inclusive, unpretentious way that every Bushwick club today wished it could. That space was the legendary, but sadly no longer, Club 57 (1978-1983). Located at 57 St. Mark’s Place, the cramped, no-frills underground venue was guaranteed fun every night. On the events calendar during one week in 1980: a dance party, a screening of Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, a debutante ball, and an art show organized by Keith Haring. The founders and patrons of Club 57 blurred the lines between gay and straight, highbrow and lowbrow, art and partying in daring and unprecedented ways. This was thanks partly to the legendary “anything goes” culture of the East Village in the late 70s and early 80s. The art world was leaving typical enclaves like Chelsea and Midtown to open up galleries in the neighborhood, which was also incubating ground-breaking scenes like punk, no wave, and queer pop — producing stars like Madonna and Cyndi Lauper (who also visited Club 57). “It was a really interesting moment in time,” says acclaimed artist Frank Holliday. Now a professor at Parsons, Holliday created sets for the plays staged at Club 57. “All the art and music and writing and everything was done in the club. Because there weren’t that many clubs that had all the artists in it. For us, we would rent the club for $25 a night and charge people one dollar to get in. It was never a money-making thing. That’s what made it such a great thing. Anybody could do anything there.”

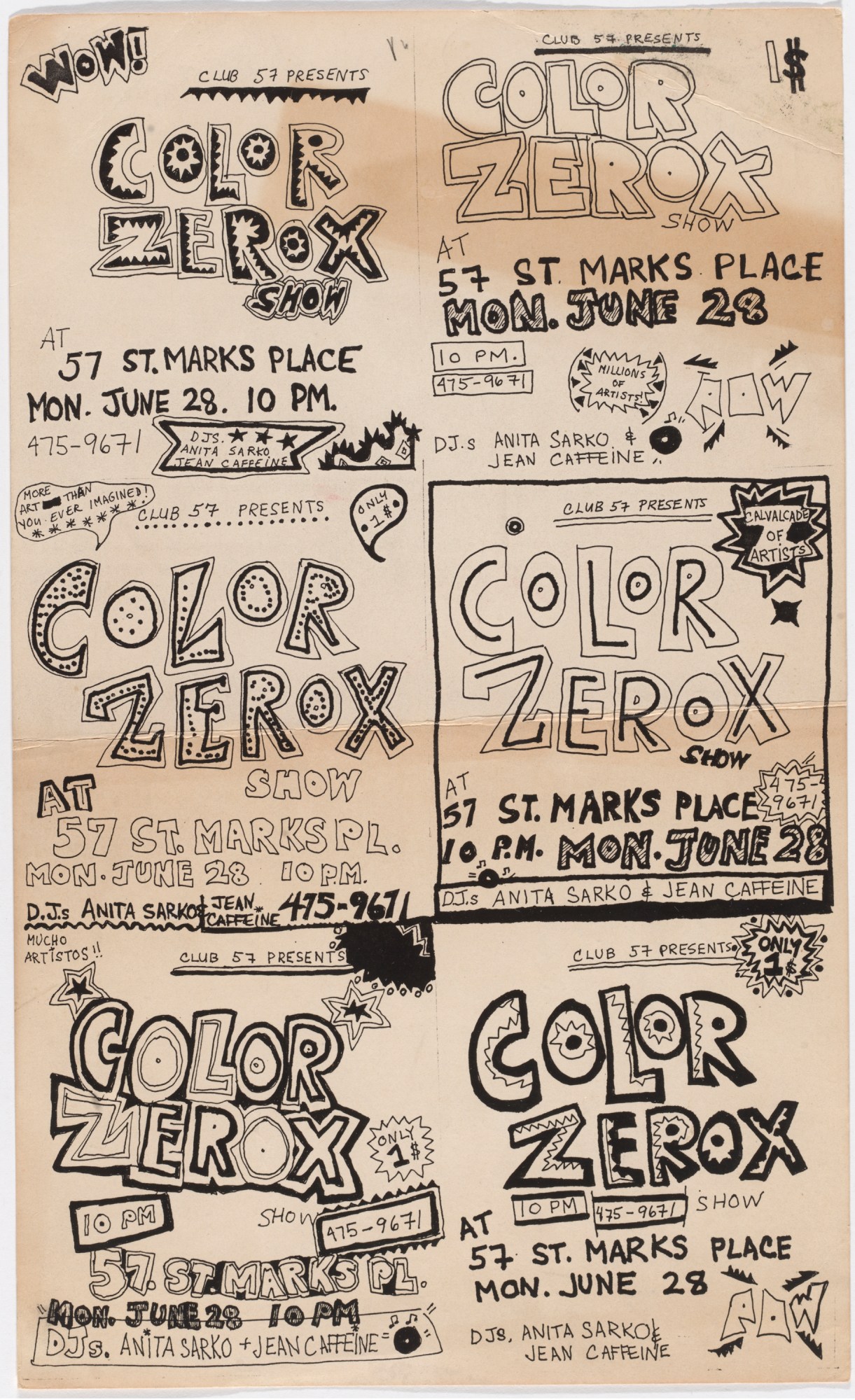

It was this openness that allowed Haring to host the art exhibition Xerox (primarily featuring works made using photocopiers) and that enabled Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman — who would go on to write the lyrics for Hairspray — to stage elaborate, unconventional musicals.

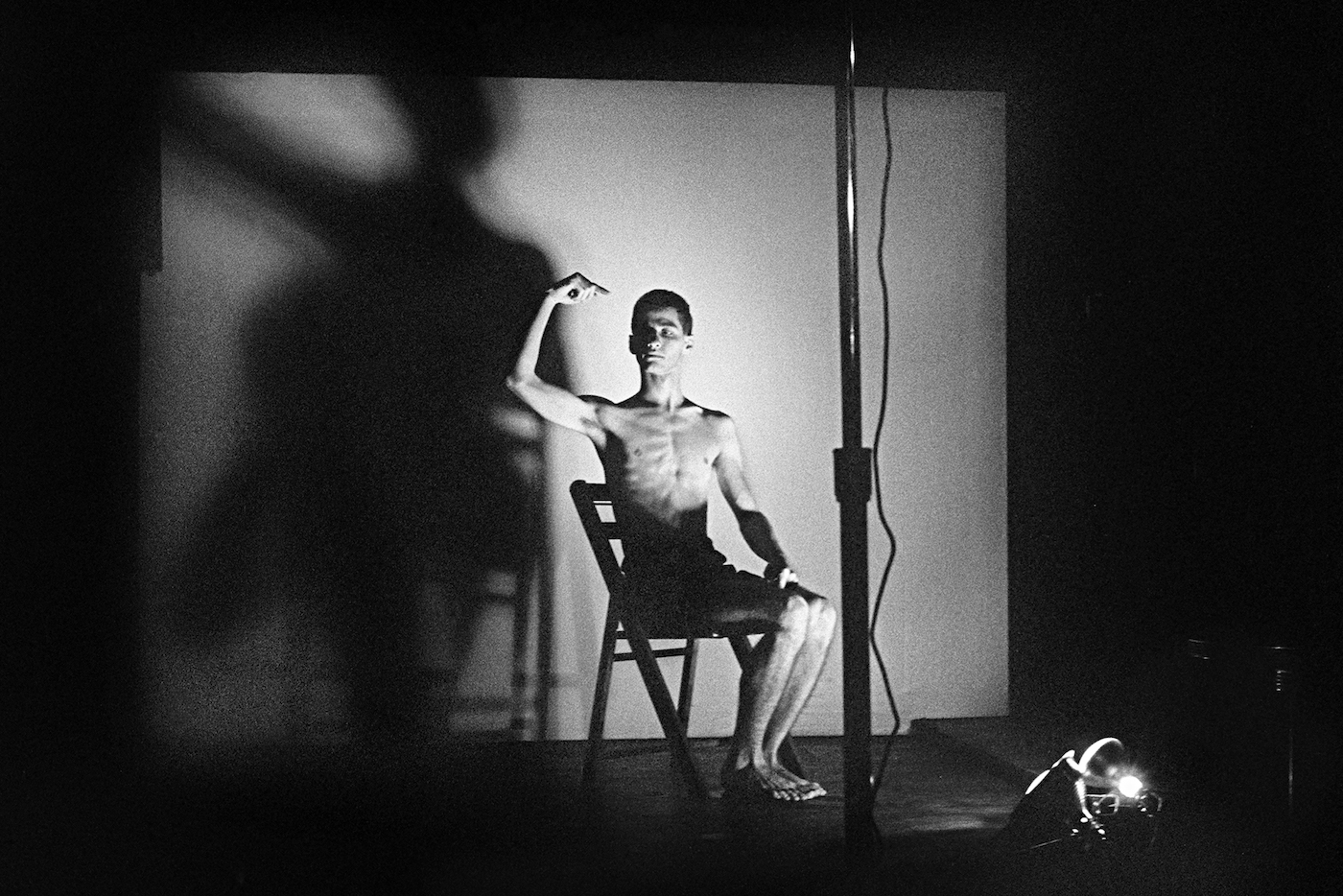

MoMA’s new exhibition about the history of Club 57, Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village 1978-1983, feels necessary and inspiring for today’s young artists. Especially when rapidly spreading gentrification, soaring education costs, and high rents have made New York a challenging place to be a young creative. You can feel the creative hunger of Club 57’s artists when you walk around the show’s two floors of xeroxed flyers, lo-fi art films, and nude portraits shot in threadbare apartments. The work points to a radical spirit shared by today’s youth and the artists and partygoers of Club 57. One of the most touching pieces on display is an unfinished short film about AIDS created by Tom Rubnitz. It shows a man in the process of undressing as an off-screen narrator screams about the public silence around the HIV/AIDS crisis. Rubnitz died from the disease in 1992 before he could finish the piece.

Club 57 was a celebration too, of course. One walk-in installation at the MoMA show — composed of neon Christmas lights, disparate found street objects, and a blaring Beach Boys soundtrack — provides a taste of the tongue-in-cheek humor almost every young New York artist, past and present, possesses. When I visited the exhibition, an older woman, presumably a former patron of Club 57, walked out of the installation, created by Kenny Scharf, overwhelmed and disoriented. “That’s not how I remembered it,” she told me with a laugh.

We called up a host of former Club 57 regulars, as well as the exhibition’s curators, to hear more about the healing, collaboration, and sweat-soaked dancing that took place at the legendary space.

Ron Magliozzi, curator of Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village 1978-1983: “Club 57 was not like Studio 54. It was only in existence for about five years. It was in the basement of a church, and it was started by Stanley Strychacki, a Polish immigrant who was an entrepreneur. He saw these people performing in the New Wave Vaudeville Show [1978] and basically said, ‘You guys should start a club in my basement.'”

Susan Hannaford, co-founder of Club 57: “Club 57 was just like a dump of a basement at first. Stanley came up to Tom [Scully, co-founder of Club 57] and I after New Wave Vaudeville, which was sort of like a punk music variety show, and asked if we would like to see his space on St. Mark’s. We sort of said yes just to be polite, we weren’t really interested. When we saw the space, we thought we could screen all of the horror movies we loved with a series called the “Monster Movie Club.” It sort of became a cult hit — we had to close down membership after 250 people.”

Sophie Cavouluacos, co-curator of Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village 1978-1983 : “New York was post-bankrupt, post-blackout, post-disco, and a new set of young people — especially art students — had congregated around the East Village.”

Susan: “Then, rent in the East Village might be $50-$150. John and I had a huge loft for $500, which everyone thought we were crazy for paying but we had jobs in film. But, honestly, you hardly had to work! You could bartend a couple times a week and be able to live.”

Ron: “The East Village looked like London after the blitz — empty lots, burning buildings, and a mix of a lot of Eastern European and Puerto Rican immigrants. It was a very scary place to go to. It kind of replaced Harlem as a place you were afraid to go to.”

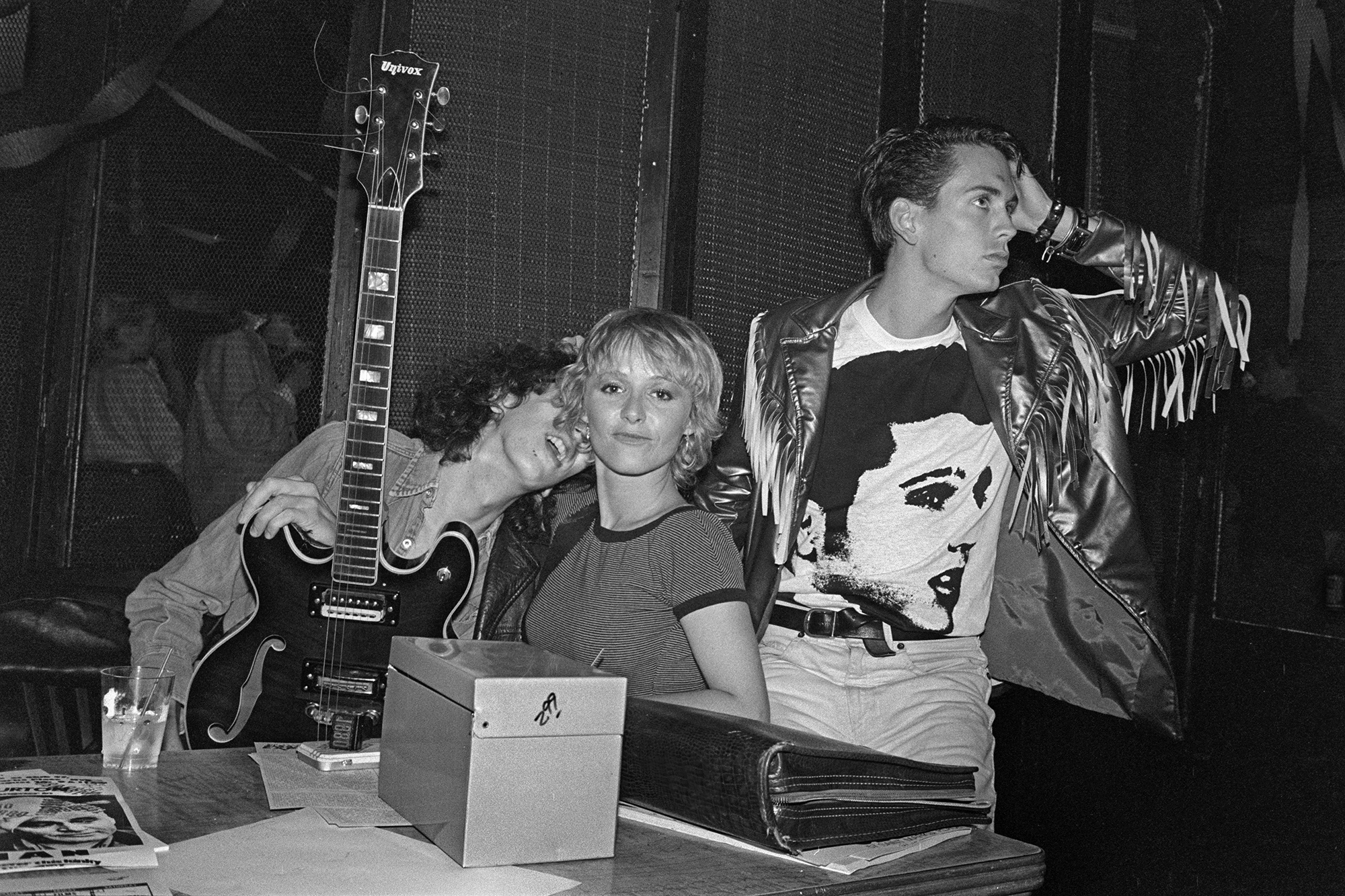

Frank Holliday, artist: “I was one of the first people in Club 57. It was dark and smelly. Susan [Hannaford], Tom [Scully], Anne [Magnuson], Andy [Rees], and Dave [Shapiro] went down to the club and there was a locked gate and it smelled and they were like, ‘Should we do a club here?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, but paint it black!’ So when it opened we would have themed nights. We had a ‘back to school’ night where everyone would dress in weird college shit and get shitfaced. Then we had a reggae night. We would do these big plays. Every night it was something different.”

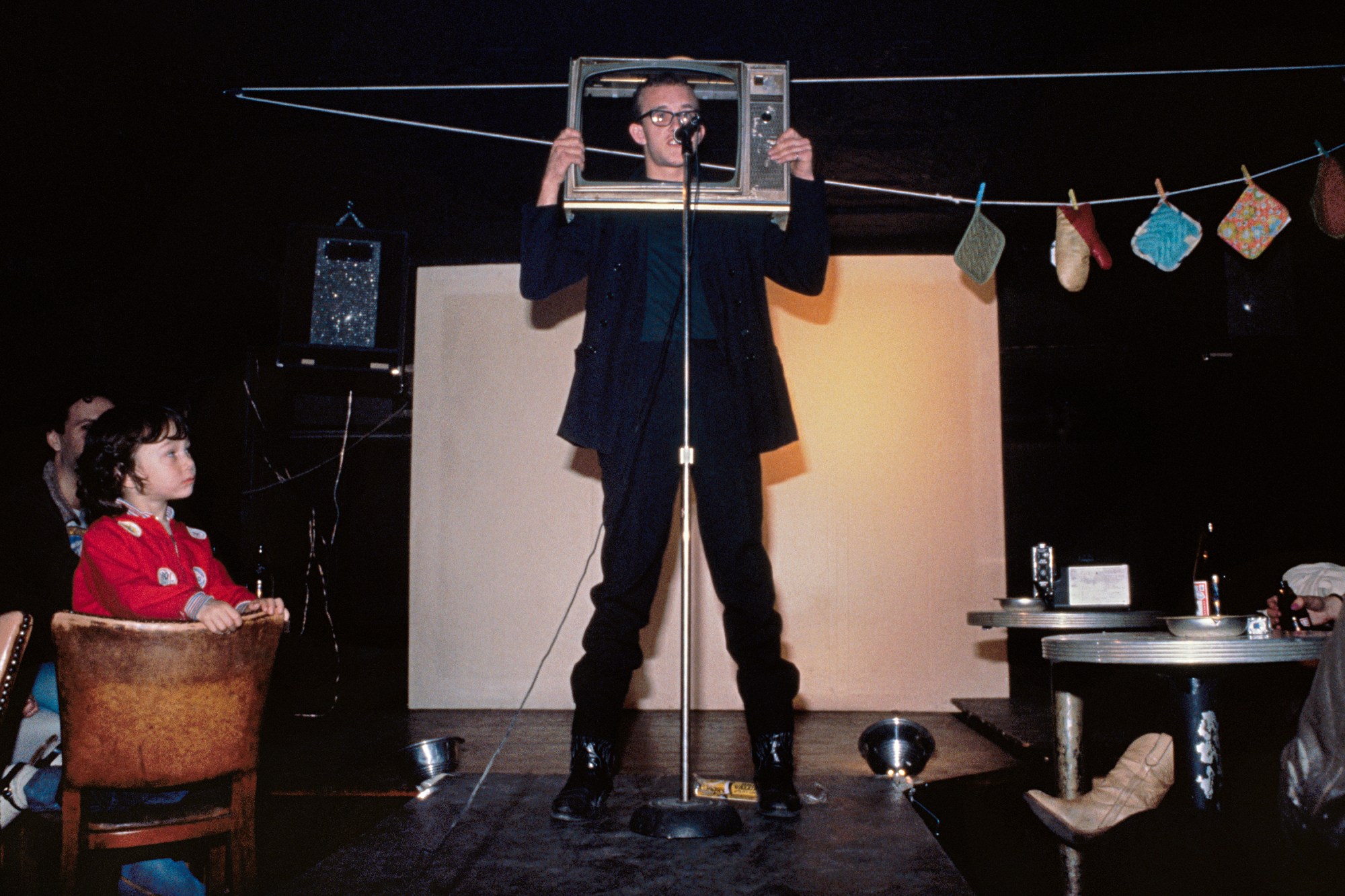

Scott Wittman, co-lyricist of Hairspray : “I remember, our friend called us saying, ‘I just went to this great place on St. Mark’s that you guys need to go to.’ So we went down there and met everyone and I said we could do something here and they said sure. We always used to say we were too rock and roll for theater and too theatery for rock and roll. Club 57 was the perfect marriage because we could basically do whatever we wanted. It was sort of this warped version of theater, plays with a sort of rock and roll spin. One or two times we did a show and then did another one and it would go on a few more nights and become very popular.”

Frank: “They would give me like $25 for the sets and that would be the budget! Andy had this car and we would go around the streets and we would find stuff for the props. I’d paint backdrops in my loft on big pieces of paper and we would stick them up with staple guns. The lights were all clamp lights. It was a very low ceiling. The backdoor of the stage was just a fire escape. I would paint beautiful backdrops and we would put them up with chewing gum and dental floss. I’m telling you, I would sit back and watch these things praying that something did not just fall off. I once made a house out of plastic so you could see what the actors were doing inside it.”

Marc Shaiman , co-lyricist of Hairspray : “Because the place was so small, if you had 25 people in it it felt crowded and if you had 100 it felt like a mob. When we did plays, the audience would be facing one way and — because the club is so small — Scott would yell, ‘Rotate!’ and the audience would have to turn around to see the next set.”

Katy Kattelmann, performer: “The only bad time I had there was when I was dating John Sex [one of Club 57’s co-founders] and he dumped me for Sean [McQuate]. We had a picnic at a park once, around my birthday, and I remember Keith Haring took pictures of me. They were very unflattering. But he made an art piece out of them, which is part of the exhibit. It’s not his usual style (it was when he was going through his Andy Warhol phase).”

Animal X, performer: “You didn’t have to feel uncomfortable. If you were sitting next to someone you didn’t know, it was very easy to talk to them because everyone was in a small enough loop.”

Susan: “The standout events to me are the failure events. When nobody came. “Put-put Reggae Night” was when we got a bunch of stuff off the street and set up a miniature golf course. It was fun because we just played and danced. The events that were jam-packed weren’t that much fun — to me. It was too small of a space.”

Katy: “I wasn’t there for the last days of the club, but when I got back into it, Pyramid [still located at 101 Avenue A] had kind of taken Club 57’s place. At Pyramid, it was more of a mix of drag and gay and straight…”

Susan: “Towards the end, crack was all over New York. Fifty percent of all my friends were dying from AIDS [including Club 57 co-founder John Sex]. It was just dismal and horrible. It was not a happy ending.”

Sophie: “In 1983, the scene was a lot different, a lot bigger. Real estate values were going up. But also it was a combination of the AIDS crisis and drugs — which decimated scenes across New York. And the last thing, which I always go back to, is scale. Essentially 100 people were co-existing and creating and partying together. It didn’t work when it got bigger and different artists, like Keith Haring, started having careers.”

Frank: “I made a lot of friends there. Unfortunately, a lot of them are dead. That’s the other thing about this scene… most of them are dead. Parsons does this lecture on the East Village and I go to speak and these kids are dressed as Keith Haring and others and everyone’s dead but a few people. It’s bittersweet because you made all these incredible relationships that you took to the edge and you have to have them in your heart because they’re no longer around. There’s Ann [Magnuson], Marc [Shaiman], Scott [Whitman], and me, but so many people of our dear friends have died. I feel like we have to represent the people that didn’t get represented then. Because a lot of the fame came after.”

Katy: “Today, the East Village is like another city. Tompkins Square is nothing like it used to be. The only place that was remotely the same in the East Village was Trash and Vaudeville, and it moved.”

Susan: “We’re about to launch the Club 57 Artist Fund. The point is not just to preserve the past, we’re interested in unknown artists that are broke. Someone who needs a costume or a rehearsal studio or even flyers. People say Club 57 was so unique and influenced so much. But there are always great people, there’s always great art. My kids live in Manhattan and it’s just not affordable. How can you make this kind of money starting out? If Club 57 did anything in the past, it was helping people and giving them a venue to show their work.”

“Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village 1978-1983” is on display at MoMA through April 1, 2018. More information here.

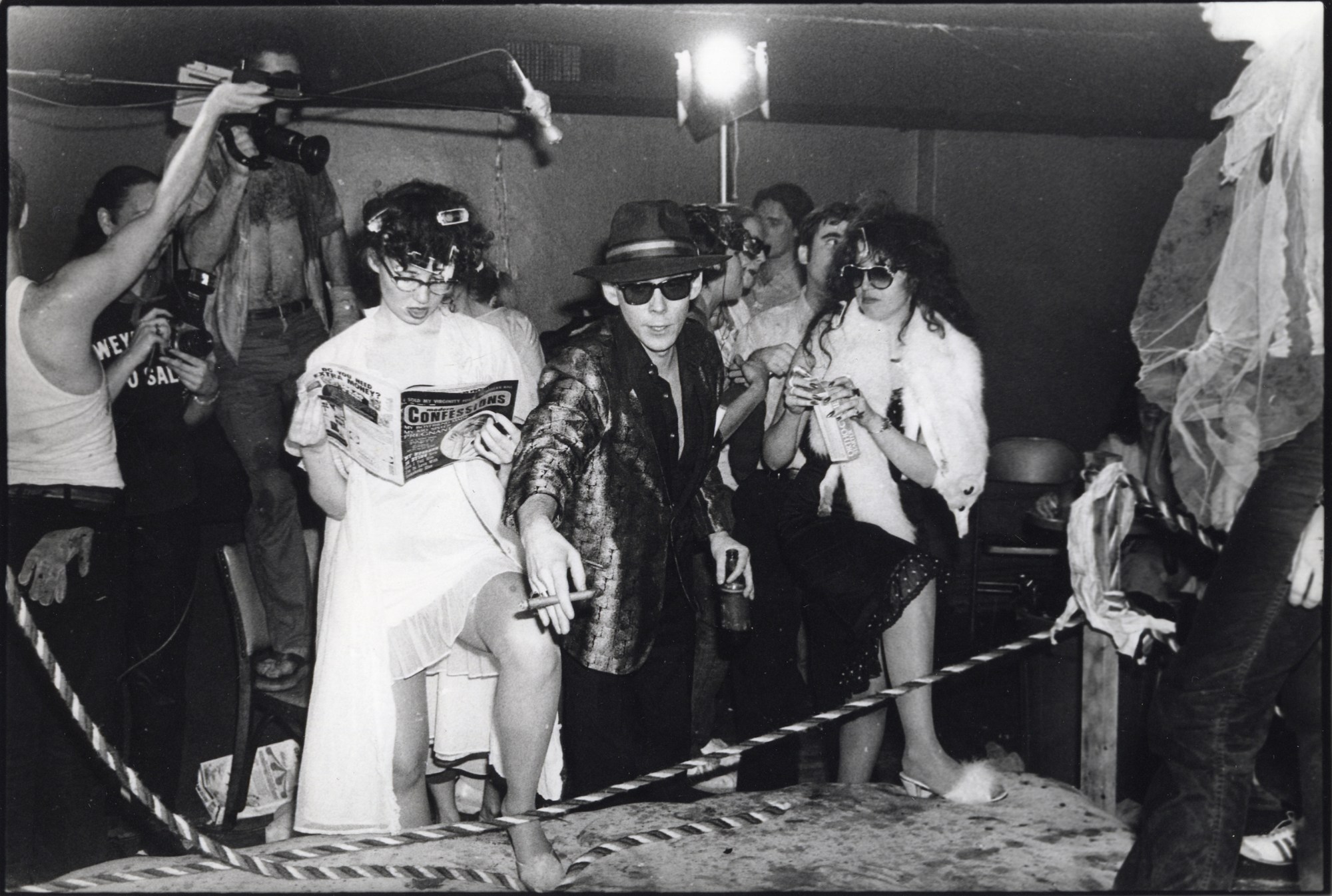

John Sex (1956–1990). Truckers Ball, 1981. Courtesy of MoMA.