Shiotani is a small and remote Japanese village nestled 29 miles from Kyoto’s centre, in the mountains of the Northern prefecture. It has a population of roughly 47 people, most of whom lead a traditional farming lifestyle. It’s where the Swedish photographer and award-winning filmmaker Anders Edström’s wife grew up. In 1993, on a visit to his wife’s family home, Anders began to capture what he saw in the town, beginning a 23 year-long project documenting the life of the village that now takes the form of an expanded photo book, Shiotani.

“In the beginning, it was not an artistic project,” Anders says. “It was in 2006 that my wife’s grandmother asked if she could see some of the pictures — because I hadn’t shown any of the photos that I had taken up until then. So, in 2008, I made a quite thick photo album for her with all of the photos. Through making this photo album, I realised [it] could turn into a really interesting book.”

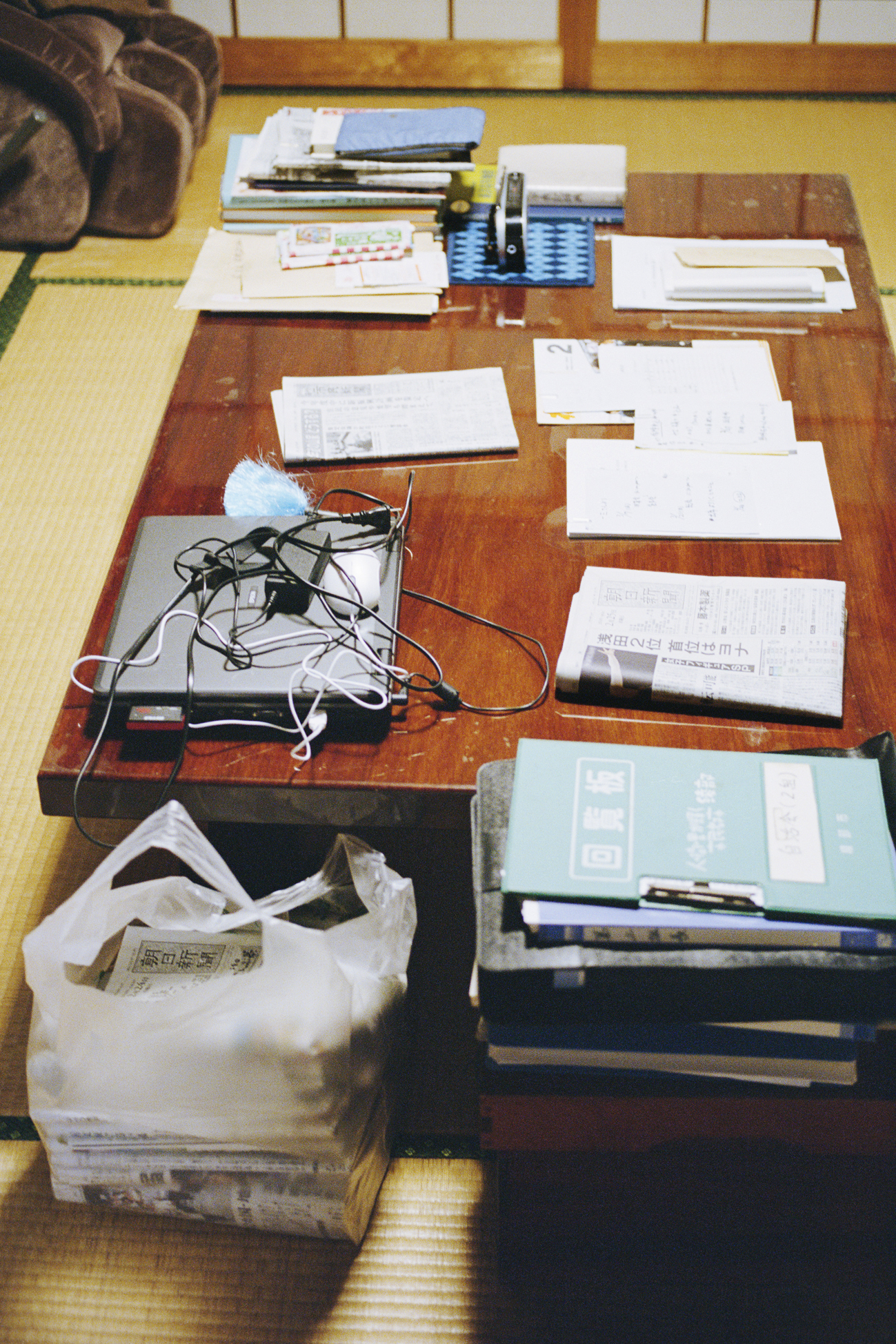

Compiled of over 600 photos spanning 1993 to 2015, Shiotani records the lives of the village’s residents in slow-moving detail. With a special interest in the more intimate pace of the Japanese countryside, Anders is drawn to the ubiquitous. Rice paddies, the movement of morning mist, summer firecrackers, snowy roads, a pour-over coffee contraption — he takes notice of scenes that are quiet and simple. It’s the daily rhythm of life, the gentle resonance of slow change, that enchants the photographer.

“When I wake up in Shiotani, everything will look the same as it did the day before,” he says. “But when you keep doing this for years, then you realise there are things changing in the world, even in the slight corner of a bookshelf. You can see that time has passed. The same goes for people. And I mean, it’s more obvious with people, but still, when you see someone every day, you can’t actually even see them age.”

Taking inspiration from the images in the book is Anders’ four-part, eight-hour feature film, The Works and Days (of Tayoko Shiojiri in the Shiotani Basin). Filmed over 14 months, the film gives a fictionalised account of what life is like as a farmer in the village.

“For me, making a photo book is very similar to making a film. There are a lot of moments where the viewer might think ‘this is not a great photo,’ but even the photographs that are not beautiful, classical photographs — when you repeat them, you arrive at something that is stronger. Having this difference in level of intensity gives you motivation to want to keep turning the pages. This is exactly my goal in making a film.”

Still, Anders threads a through-line between memories, both momentous and every day, proving that the two can constantly be in conversation with one another. In order to bring to life a “photo-roman, a novel in pictures,” as Jeff Rian writes in one of Shiotani‘s essays, Anders recasts and curates his collection of familial photos to portray the seasons of love and loss. In the book, the passing of Anders’ wife’s grandparents is conveyed through careful documentation of Japanese ritual and tradition. Dressed in black, family and friends gather for two funerals — and, for the first time, within these brief moments, frames are populated with more than a couple of close relatives. Elsewhere in the book, we witness the effects of industrialisation on a rural landscape, and the detrimental effects of government land management. Death punctuates this photographic passage of time.

In these photos, no one takes notice of the camera, or Anders, ostensibly. Creating this photographic intimacy and trust with such delicate levity took time. Not speaking Japanese initially, the photographer had to overcome the challenges of being a foreigner in another country. Becoming familiar with the residents of Shiotani was enabled by mutual respect for a quiet way of life. “Only after a while, when we started to get to know each other better, did they realise that I was just this Swedish guy who likes to take pictures.”

Credits

Photography Anders Edstrom