Anne Imhof’s new work at the Tate Modern is called Sex, although she’d originally considered calling it Death Wish. Sex and death is, as the truism goes, is what you can reduce all art to. But then Anne’s art is, in many ways, all about reduction; finding the essence of something and confronting her audience with it.

Her rise has been meteoric — she graduated from the Städelschule in Frankfurt, in 2012 and by 2017 she’d won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for Faust; a work that felt era-defining in the way that it tapped into an unease about contemporary life, and how we live right now. It was revelatory and revolutionary, shockingly new and raw and confrontational. In her choreographed performance pieces you can find a sense of the modern sublime — this mixture of fear and beauty, the horror and the majesty. We are lost in a maze of fluctuating tableaus, all these endless, empty, repeating images.

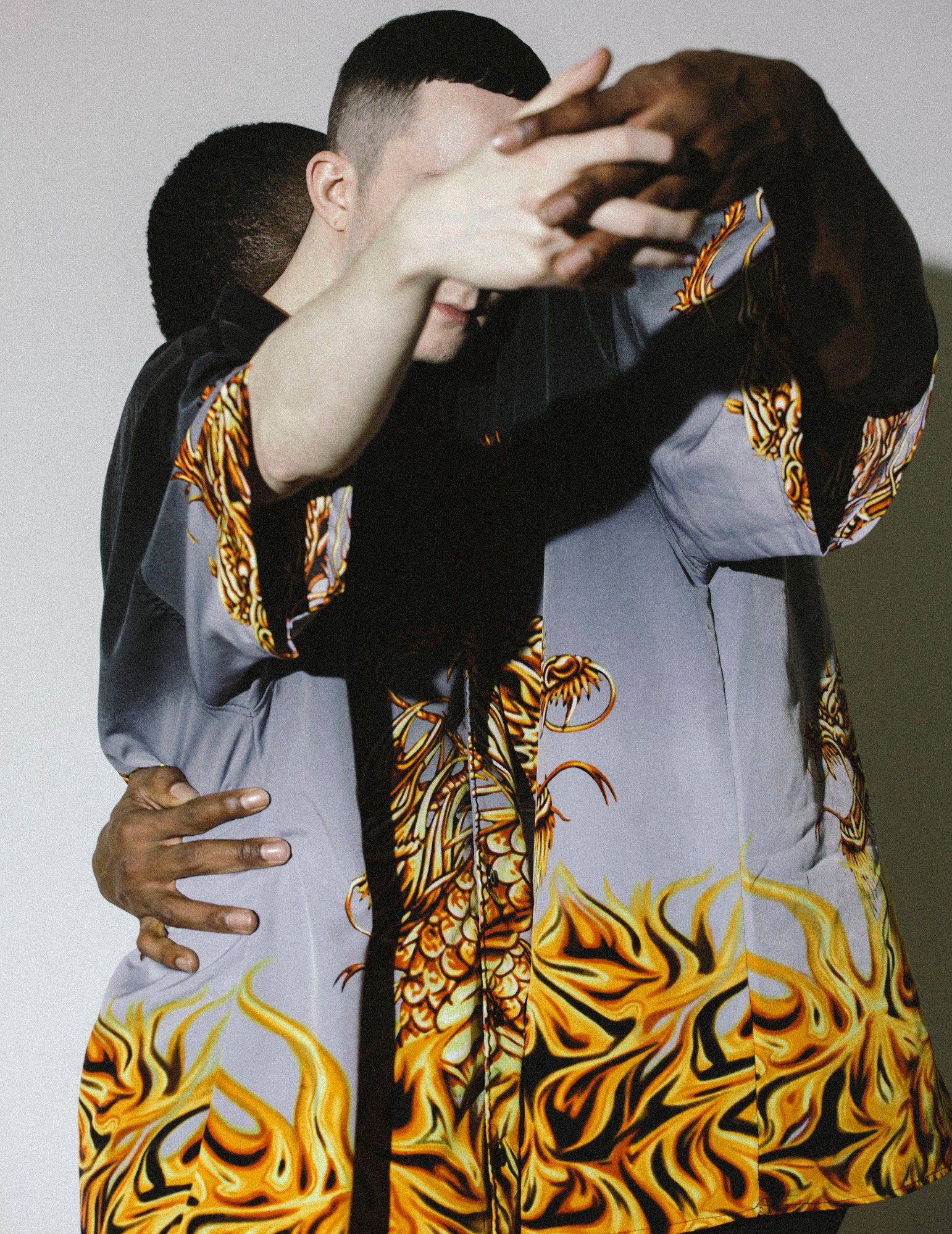

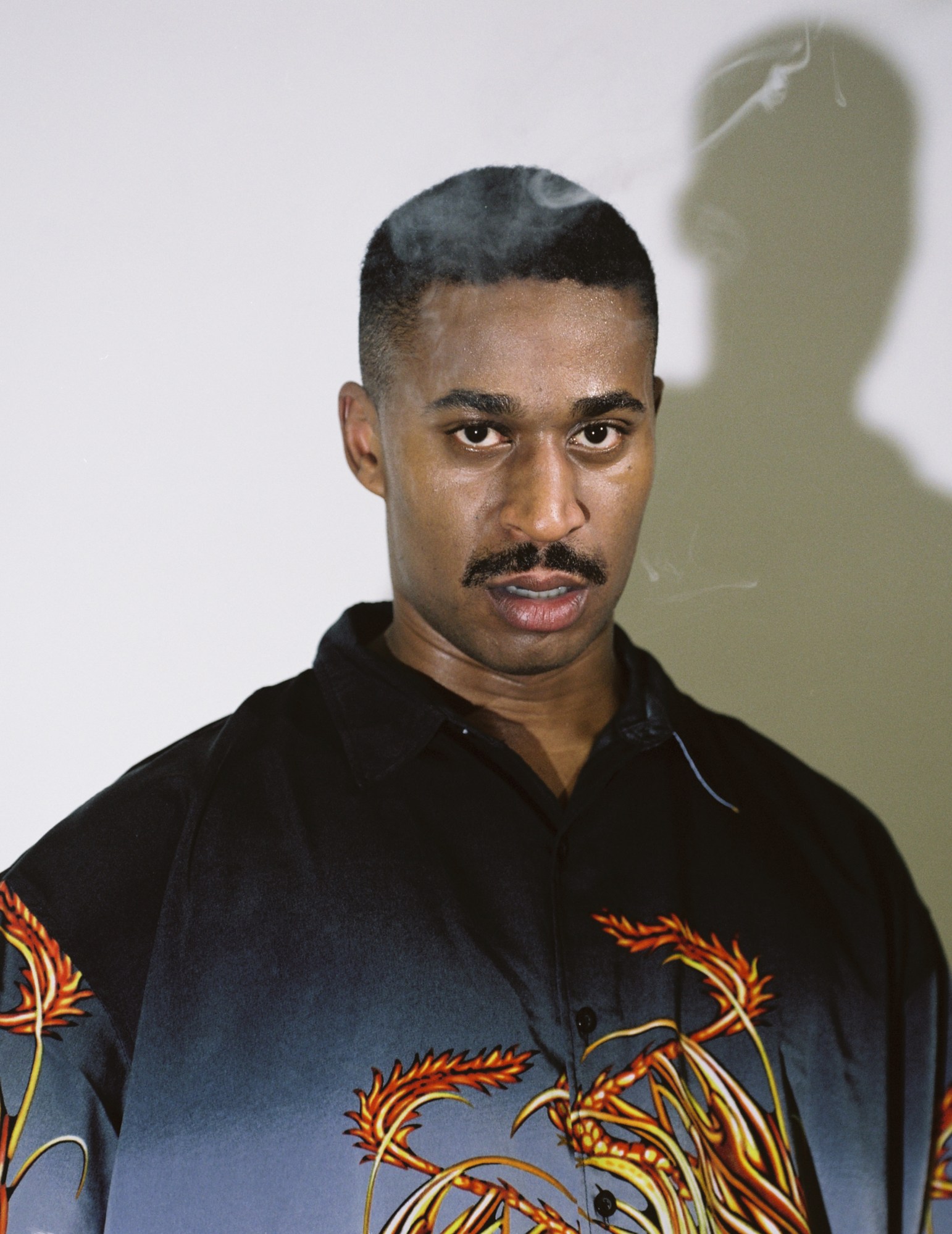

In Sex, this effect in heightened by the sheer scale of the performance. Unveiling over four hours across the Tate’s Tanks venue, Anne’s performers move across and between the two spaces in a loose sequence of actions. They have a listless intensity to them, an impatience and an angst (the title of another Anne’s works). Her performers — a core group formed of Eliza Douglas, Billy Bultheel, Lea Welsch, Frances Chiaverini, Mickey Mahar — vape, drink, paint, play guitar, sing, climb, use phones, lounge around, lie down, burn flowers. They undertake more “traditional” performance choreographies too; of interlocked bodies, marching, movement, rhythm, ritual and repetition.

Anne is a world builder and a scene setter — her works are about atmosphere and feeling rather than narrative. Anne’s sportswear clad performers seem to hold a mirror up to some contemporary anxiety — a vacuousness, a feeling of emptiness, trapped, performing strange Sisyphusan tasks. There’s something startling about the way it implicates the audience in the performances, turns the viewers in voyeurs, as the performers bleed into and out of the audience. They’re dressed the same. They look the same. They’re dressed in sportswear, for the club, for some freaky techno party on the outskirts of a city on the outskirts of Europe.

Sex happens across both of the Tanks — they are mirror images of each other. In fact, mirrors — doubling, symmetry, balance — are key to reading the work, which is more about feeling than anything explicit. In one room the audience juts out on a raised metal viewing platform, the performers below them. Around the circular room are a series of raised white platforms, that they sit on. The effect is quite coastal; heightened in the other room by a huge wooden pier that protrudes through the middle of the room, the audience on the floor, looking up.

A corporate style, glass barrier, runs around one edge of this tank, linking it back to the first. Across these rooms is strewn the debris of a party, a night club, or a domestic life. This feeling of something about to happen, or in stasis — unopened cans of Guinness and Stella, ketchup, phones on bed, bags of sugar, mattresses, speakers.

The spaces evokes, at times, the wild, half-seen, expanses of a landscape and, at others, the private sanctuary of the bedroom. The piers and platforms conjure this feeling of a sea, the curvature of the tanks a constantly receding horizon; this constant, uneasy, shifting of focus. The crowds swarm through these spaces too, following the performers, led on a chase. The crowds form like rumours across nothing — waiting, or anticipating, unsure where to look or be.

Sex, as an exhibition, in its specific themes, is all about the binary, doubling. From the word sex itself, which can mean gender or intercourse, both of which are kinds of performance anyway. The paintings that line the walls are divided down the middle into two blocks of colour, their surfaces scratched into. They evoke sunsets or sunrises, abstracted landscapes hung as portraits. The piece itself seems to explore further clashes between nature and technology, classical and techno, the land and the sea, portraits and landscapes, pain and pleasure, hedonism and despair, beauty and rage, presence and absence.

It is slightly unsettling, the feeling Anne’s landscape conjures in you, as you move through it. Like being lost in a club at five in the morning, strobes in the distance, half heard echoes of bass, muffled loudness, this feeling of something happening elsewhere, a slight sense of dislocation. And then, the performers rear into view — a group come marching through strobes to aggro techno, grappling with each in some violent, tense, sexual ballet. The performance rolls through a series of climaxes, unfulfilled and delaye. Intensity gives way to emptiness; a brief quiet moment after the action seems to be the strangest.

What is at the heart of Sex? A mirror to the emptiness of modern life, maybe. It is, not particularly ‘sexual’ more an exploration of all our vacuous rituals and strange repetitions. This nightmarishness of absence of action — you’re stuck wandering aimlessly around with your camera phone out, trying to capture something, bottle up some essence. This is what makes these works so effective and interesting. This unease, the way the performance seems to question the viewer, accuse them of something. What are you looking for? Why are you even looking?