The sight of millions of women, men and children protesting across the globe following the inauguration of President Donald Trump should serve as a stark reminder of how much scrutiny the new leader of the free world can expect on womens’ rights. The viral nature of the protests however, also pointed to the fact that the issue remains a very real one: it’s still hard to be a woman in 2017. It’s harder still to be a woman of colour. In this context, Tschabalala Self establishes herself as one of the most relevant and insightful black female artists working today.

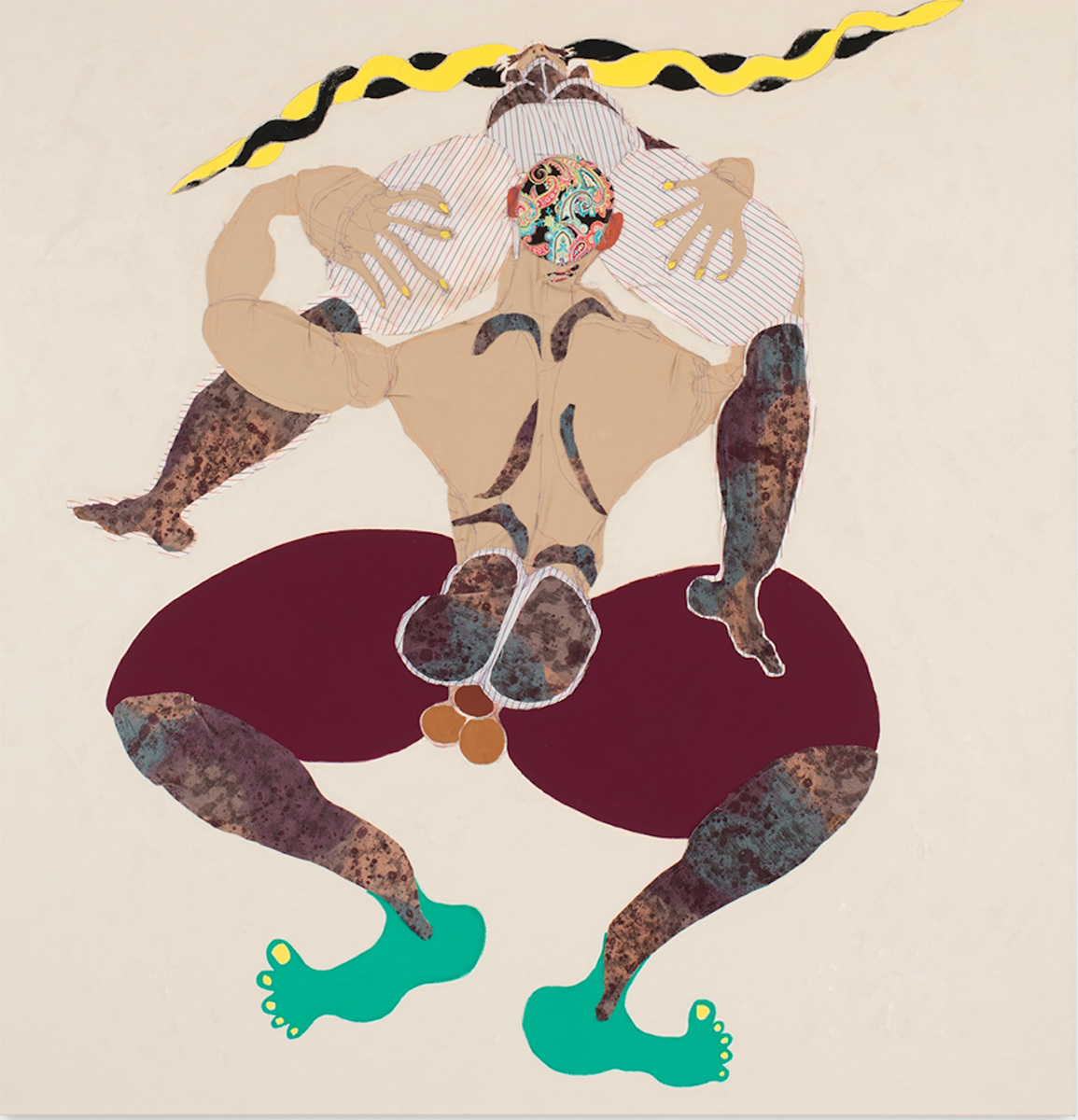

Utilising oils and mixed media, her pieces are invigoratingly colourful and vibrant, confronting and playing with racial and sexual stereotype: her protagonists – all black women – are depicted in confident, kinetic postures, with glorious emphasis resting on muscles, thighs, buttocks, and breasts in full flush of power. However her figures are by turn also coy and personal, human. Together they constitute a captivating, insightful marriage of the erotic and the psychological. Tschabalala is currently exhibiting at the Parasol Unit in Hackney – her first solo UK show. Hers is a rare collection of visceral and cerebral beauty, only empowered by being so highly politicised.

Read: A beginners guide to pioneering black-British artist Lubaina Himid.

What significant experiences did you have growing up with your own body and how did it affect your work?

I grew up in Harlem but went to elementary school on the Upper East Side, as public schools were better there. So maybe for the first time I was in a predominantly white environment, and experienced being perceived as ‘different’. I never felt different, I just felt perceived as such: a kind of double consciousness. Luckily, I was able to hold on to my personal identity but I had to start to acknowledge other peoples’ realities that implicated me in them.

As I got older, I had to perfect those skills for my own personal safety. Living in a female body, living in a black body has brought the understanding that those expectations you have for yourself don’t necessarily match the expectations of other people out in the world. Especially in regards to your body, how it should be treated and respected.

How do you feel the black female body is perceived?

I always figured that all the issues that contribute to sexism and racism would clarify as I got older, or would start to make sense, or situations would get better – but I have to say, the issues that promote or allow these things to be persistent in our culture, they’ve become more and more confusing. That’s also what my work has been about. I’m trying to name what the black body signifies; to understand why the black body seems to incite this kind of excitement, or kind of anger. I think if you can be sincere in your own mind about your aspirations and your fears and your anxieties, that kind of honesty will allow you to have empathy with others – and I think empathy is the only way to really understand other people’s circumstances: to see them outside of a stereotype or outside of being ‘lesser’ than you. The one thing I have learned, I think the root of all of these social issues is peoples’ desire, or need to feel superior.

“The personal is political.” – how do you view that statement in terms of your art?

I have the same desires as everyone else in terms of wanting to know themselves, to become who they imagined themselves to be. But this is an essential issue: for victims of sexism and racism, it’s very hard to grow up into yourself and to try and figure out who exactly you are, when you’re constantly being told what you are. It’s especially hard to do that when what you’re being told is not something necessarily aspirational, something against your development.

I try to make a huge variety of characters, to have them enacting different feelings at different moments, even positions. I want to give them a wide variety of possibilities and ways in which they can exist: just giving them the space to be, to exist.

The most recent show I did was basically about a relationship between two black lovers. Telling a story like that I can talk as much about politics as I would with a story about an individual fighting against prejudice. Whatever’s affecting you as a political body is also affecting your personal body, your personal space. You’re living within it.

Read: The womanhood project is the new photography platform urging women of the world to unite.

As a black female, what are your thoughts on the changing rhetoric and cultural allowances moving from the Obama to the Trump administrations? How are your friends and family feeling?

I think everyone was happy about Obama because he was clearly the best candidate for the job. But something like that, it meant a lot to a lot of people in regards to their relationship to whiteness. I met many people who said that it was important to have a black president because they’d only ever had white presidents – but it’s important to realise there remains a wider black history, one that exists outside of America. Black peoples’ history did not begin with the colonisation of Africa. There needs to be more diversity around stories and an understanding of black identity outside whiteness. If people focused on those stories it might be more beneficial to their self-esteem or world-view.

The imagery of the Obamas in the White House did do some of that – it was a separate narrative; it was almost a fantasy narrative that allowed the community to see black people in a different light. The imagery of him being there, the weight that that image held, especially within the black community, it opened up new channels in peoples’ minds about possibility. Their whole idea about what their life could be in this country changed. Especially children, you know?

The situation we find ourselves in now, for some communities that was uplifting and for others it was something that was almost apocalyptic in its devastation. Everyone wasn’t happy to see a black person in the White House. If anyone wasn’t sure about that before, they know now.

Do you feel your work and its lens is more important than ever?

Like I try to say to people, the images that are put out by society and culture in general, they really affect peoples’ self-esteem. A lot of racist peoples’ self-esteem is based on the fact that they feel secure and superior in their whiteness. If there’s any kind of threat to that, it’s a threat to their whole world-view. I wasn’t surprised and I don’t think that anyone else was surprised at the uptick in racist attacks after Obama won, people were angry and felt they were losing their whole position in society. Other peoples’ equality was a loss to them – other peoples’ equity was a loss to them. It’s hard to defend your white supremacist world-view if there’s a black president.

I have to say honestly that the people who’ve been most deeply affected in terms of fear and shock since Trump’s win are my friends in the white community. I think that most people of colour have already acknowledged that this is/ was how the country is like. I don’t know how shocking this is to the average person that has experienced racism on a near day to day basis throughout their lifetime. Only those who haven’t experienced it finally understand that this is a real issue, that it’s not an exaggeration. At least now more people are talking about it.

Harlem is seen as predominantly black community – is that the kind of space that acts as an incubator for black thought and consciousness?

Maybe less so now, but at different times in its history, I definitely believe so. The thing that I really love about Harlem – over some of the many other black communities in America – you have black people from all over the world here: you have a huge black American population, but you also have a huge black population from the islands, Dominicans, Jamaicans, a lot of people from West Africa are here. I think that affected me a lot growing up – my family was very Afro-centric, and we also had a lot of family friends who were black but were not black-American, so I always felt that I was never bound to this one ‘black American story’. My parents were always very serious about Africa and read lots about it, and in some sense drew a certain self-esteem that goes hand-in-hand with the consciousness of an African heritage and identity rather than an American one.

My painting ‘Bodega Run’ is special in the sense that it speaks to the diversity of the black community in Harlem. And the reason for the prevalence of that kind of business, of selling little cans of food and things is because there weren’t that many supermarkets here. Harlem was effectively a food desert. You go to other neighbourhoods and they actually have proper stores; the bodega sells just as much food as it does cigarettes and beer – so you see everyone from the community there, it’s an intersection of sorts.

Critics mention the inflections of Chris Ofili in your work… Did any artist particularly influence you in your artistic upbringing?

I feel like I spent a lot of time looking at all the black contemporary artists working now – Ofili, Wangechi Mutu, Mickalene Thomas, Kerry James Marshall, all of these people have been in my mind whilst I’m in the studio, Kiki Smith, Louise Bourgeois are constantly circling in my mind. I’ve always tried to educate myself as much as possible with art, to see it in person, to see those people as individuals and as makers. In one way I’ve looked a lot at craft art, from communities of colour at home and abroad, works that can exist in a black vacuum. Art that’s black for blackness’ sake; so when I have travelled to the Caribbean or to Africa, I saw black artists in a different environment that wasn’t so dictated by whiteness: not in reaction to, or in conflict with, or in competition with. Existing outside of it.

Read: How artist Polly Nor uses frustration, anxiety and sadness to fuel her creativity.

Tschabalala Self’s first UK exhibition is currently on show until 12th March at Parasol Unit, N1 7RW.

Credits

Text Karim Khan

Images courtesy of the artist