American drag and ballroom culture arrived with the liberation of Black people following the Civil War. Born into bondage in 1858, William Dorsey Swann — known to his friends as “the Queen” — began organising secret drag parties after moving to Washington D.C. in 1880 to create a space for young Black gay men to express their true selves. Inspired by the antebellum masquerade balls, popularly known as “grand rags”, William flipped the script and invented drag. Donning the most fly finery of the day, William and friends did themselves up in silk gowns, long trains, corsets, bustles, and delicate footwear for their very own drag balls.

In turn, the government persecuted William, initiating a series of raids and arrests that would lead to 10 months imprisonment under charges of “keeping a disorderly house”. Although the press and burgeoning psychiatry community viciously maligned William, he would not be cowed. He became the first recorded person to file a legal complaint against queer discrimination — a courageous move at a time when same-sex activity between men and cross-dressing were treated as criminal acts.

Although William was not an activist, his actions set the groundwork for movements to come a century later. After retiring in 1900, William’s younger brother took up the mantle, running the DC ball scene and creating costumes for notable Black drag queens like Allen Garrison and “Mother” Louis Diggs. Although the drag scene was underground, the forces of Christian theology and white supremacy could not stamp it out.

Up in Harlem, the Hamilton Lodge on 155th Street and 8th Avenue became the heart of New York’s drag scene. Founded in 1869 by the Grand United Order of Odd Fellow, Hamilton Lodge hosted political events, church sermons, beauty pageants, academic lectures, and, most famously, a drag ball that drew thousands during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 30s. People of all genders, sexualities, races, and ages freely mixed. “The era not only allowed African American artists to experiment with and reinvent their crafts,” writer Thad Morgan notes, “it also saw popular Black artists experience and explore gender, sex and sexuality like never before.”

Throughout the 20th century, the ballroom scene continued to evolve. Although rooted in the Black LGBTQ community, as drag grew into pageants, it became co-opted by white judges imposing European beauty standards. After a white contestant was crowned at the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant in Philadelphia, Crystal LaBeija clapped back, declaiming discrimination against Black and Latinx queens.

In 1972, Crystal and Lottie LaBeija founded the Royal House of LaBeija, the first of its kind, in response to the racist practices of the 1960s drag pageant scene. Creating a home for Black and Latinx LGBTQ youth who might not have any other system of support, the House of LaBeija introduced a new model that provided a “Mother” and a “Father” guiding their “children” to success in a cruel and hostile world.

The House of LaBeija held their first ball in Harlem, introducing house culture to the ballroom scene. It quickly took off with new houses named for founders like Willi Ninja, Paris Dupree, and Mother Juan Aviance, bringing forth their own styles of vogue. As a sanctuary for the exploration of gender, race, and culture, balls have become an incubator for self-actualisation, allowing participants to express their dreams, desires, and creativity in equal part.

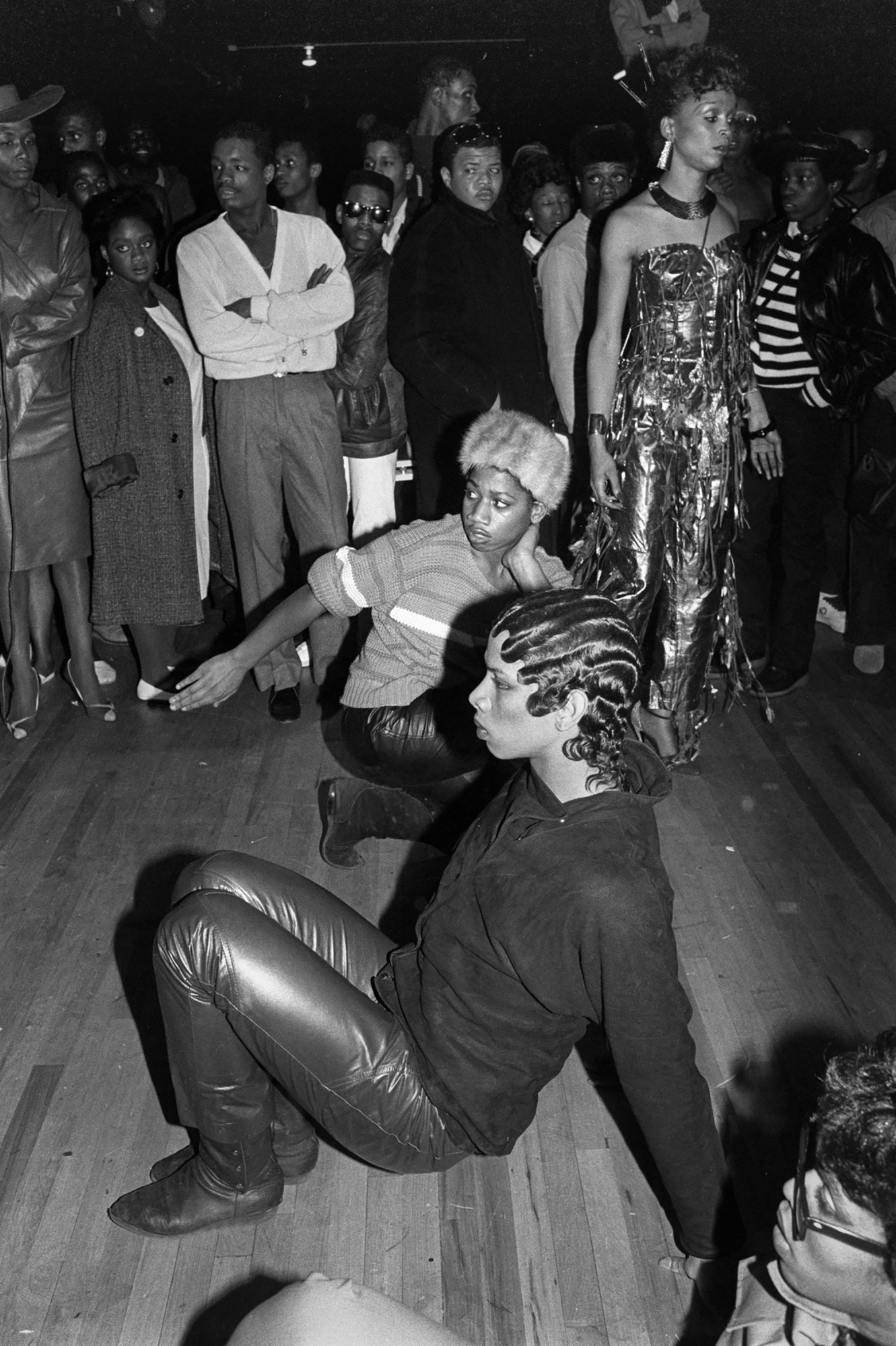

As fate would have it, American photographer Mariette Pathy Allen found her way to Harlem in 1984 to photograph one night at a house ball. Mariette first chanced upon the genderfluid community during New Orleans Mardi Gras in 1978 via a group of crossdressers at her hotel. Captivated by their energy, she began a journey that would take her around the globe, documenting the culture when it was still deeply underground. As a photographer, Mariette recognised the role she could play in people’s lives, creating portraits that uplifted and empowered them, celebrating their beauty and style when gender-bending was still very much taboo.

By 1984, Mariette was married with two children, doing small photography jobs for publications while also documenting the transgender community that would later become the centre of her groundbreaking first book, Transformations: Crossdressers and Those Who Love Them, published in 1989. While studying at Columbia University, her husband became friends with a man named Ivan, who was connected with people in the Harlem House Ballroom scene. Mariette received an invitation and decided to go, creating a collection of magical portraits from one night at the ball now on view in House Ball, Harlem, 1984 at ClampArt in New York.

“The ball officially began at midnight and ran until eight in the morning,” Mariette says. “I arrived around 10 to photograph people getting ready. It began around 12:30, and there was an announcer introducing the categories like Face, Body, and Femme Queen Realness. Everyone looked amazing, so beautiful and young. They worked to put their costumes together, and everything was so precise. Even though it was a competition, there wasn’t any kind of meanness or fighting. It was a supportive environment. This was a happy occasion, where people were proud and presenting themselves at their best.”

The sense of community can be seen in Mariette’s photos, which capture both competitors and audience members at a time when few were documenting the scene. Long before digital technology made camera ubiquitous and affordable, most people trotted out the camera for special occasions and only photographed those they knew. To have a stranger ask to take your photograph was an act of affirmation and admiration, akin to asking for your autograph. “Who me?” Yes, you, indeed.

“I have always been respectful to the people I photograph whether I speak to them or not,” Mariette says. “I’ve always been careful that people were aware that I was taking their picture and that they were comfortable with the idea. I was an outsider because I’m not trans, but I understand from a deeply personal level what it means to wonder who you are and to feel that you have to adopt certain roles as a man or a woman. Who made that up?”

Mariette first began to question gender roles as a high school student after reading Margaret Mead in an anthropology course. “I had this fabulous sense of relief when I learned that there really are no rules; every culture creates its own set of habits. I began thinking about what adults said and wondering if they were blind or just making it up to fool children. I thought, this can’t be right.”

Through photography, Mariette met the people who were living the questions she was asking herself and quickly discovered that she could use the camera to celebrate and uplift the people who refuse to conform to society’s oppressive views and have the courage to be true to themselves. In her portraits, gender is just one aspect of the many facets of identity, one that is part of a greater whole that reveals the extraordinary beauty and complexity of our shared humanity.

“I had something I could offer,” she says. “There’s nothing more exciting than knowing what you love to do also does good. That’s the top, isn’t it?”

‘Mariette Pathy Allen: House Ball, Harlem, 1984‘ is on view through 16 July, 2022, at ClampArt in New York.

Credits