Stef Mitchell’s story originally appeared in i-D’s The Icons and Idols Issue, no. 359, Spring 2020. Order your copy here.

Every time I go back home to Australia I get this uneasy feeling. Last year in Sydney I overheard a conversation. People were discussing the situation surrounding young adults in the country. They were talking about the rise of violence, especially with boys. That there’s this sense of loss and confusion around being Australian at the moment. National identity has always been a complex part of the Australian narrative. For a white Australian, national identity means you’re the offspring of either English convicts or people who came here to start a new life less than four generations ago. I’ve known for a while that a large portion of one side of my family were wiped out during the Holocaust, but the Australian side of my family history was always vague. A lot of the documentation was hidden by my family. But recently I found out that my great-great-great-grandfather was the product of convicts – he was conceived in a prison, while his parents were serving life sentences. My Australian heritage is a combination of people who survived chain gangs and arseholes who caused catastrophic damage to an entire Indigenous population. They charged into a place they didn’t belong, held mass executions and stole Indigenous children from their families. The government only officially apologised to the Indigenous population in 2008, far too late, especially as the destruction caused by this colonial mindset is still very much playing out in the country.

When this narrative is your national heritage, you arrive at a pretty confusing dead-end of an identity crisis. Inheriting such a dark history, combined with the isolation of being cut off geographically from the rest of the world, results in a difficult and particularly chaotic coming of age for many young Australians. It’s raw.

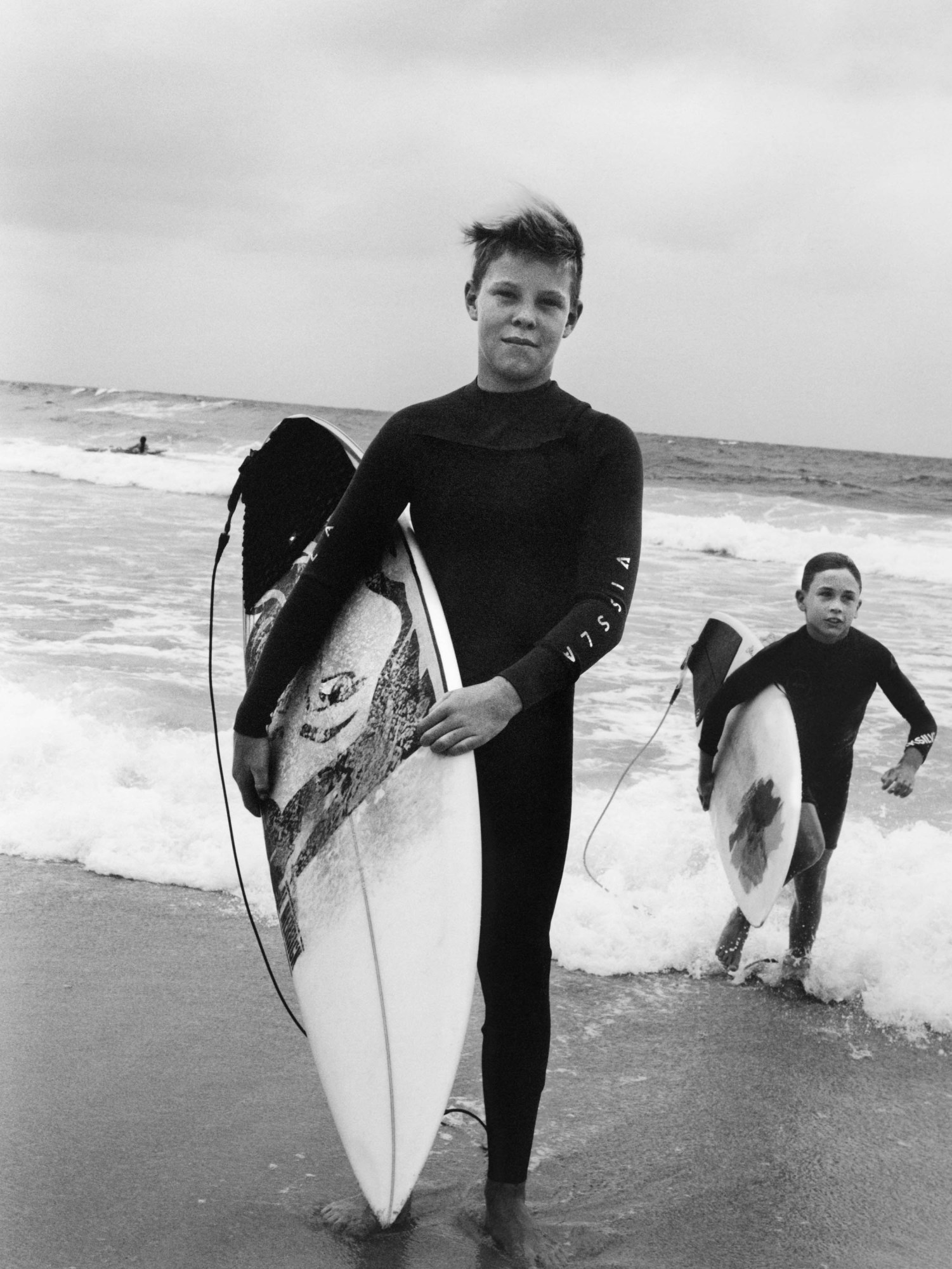

Indigenous or not, a huge part of your childhood is carved out by nature herself. The actual land is part of our identity. You’re taught that if something looks beautiful it will probably hurt you. You’re taught to respond immediately to changes in weather. You learn that places are alive and have memories that have nothing to do with you. And as you learn what your white ancestors have done, it’s hard not to feel vaguely rejected by the land. You wonder if maybe the harshness of the sun and the thrashing waves have always been messages, signalling that you don’t belong here.

I moved to New York 10 years ago and became accustomed to a different intensity, to the human buzz of the city. Every time I go back home to Australia I’m always reminded of a different power, of my small place as a human on the earth.

I woke up one morning in November 2019 to text messages from my family. Soaring temperatures and winds had joined multiple fires together into something called a “mega-fire”. Highways were closed, the sky had turned an apocalyptic dark red, the air wasn’t safe to breathe. After the initial panic, I couldn’t help but think, again, that the land was angry and wanted us out.

In December, I flew home and witnessed the reality of a continent on fire. Real danger feels like the stillness of the bush – once powerful and aloof and wildly alive – turned to charcoal, unmoving and staring straight at you. Real danger looks like endangered wildlife you were taught to be wary of crawling to you begging for water, their habitats destroyed.

Back in the safety of New York, it’s hard to see things the same way I did just a month ago. It’s hard to ignore the parallels between what I knew to be an Australian crisis and a global one. It’s hard to ignore that our enemy is no longer just our oppression, the struggle of being seen for who we truly are. Our greatest threat is human extinction, and any kind of divide no longer serves us. When your family is threatened by 200ft high flames caused by global warming, you stop thinking in terms of sexuality, religion, race, age, pronouns. All these labels we take refuge in suddenly feel like discussing your favourite pair of socks while someone holds a gun to your head.

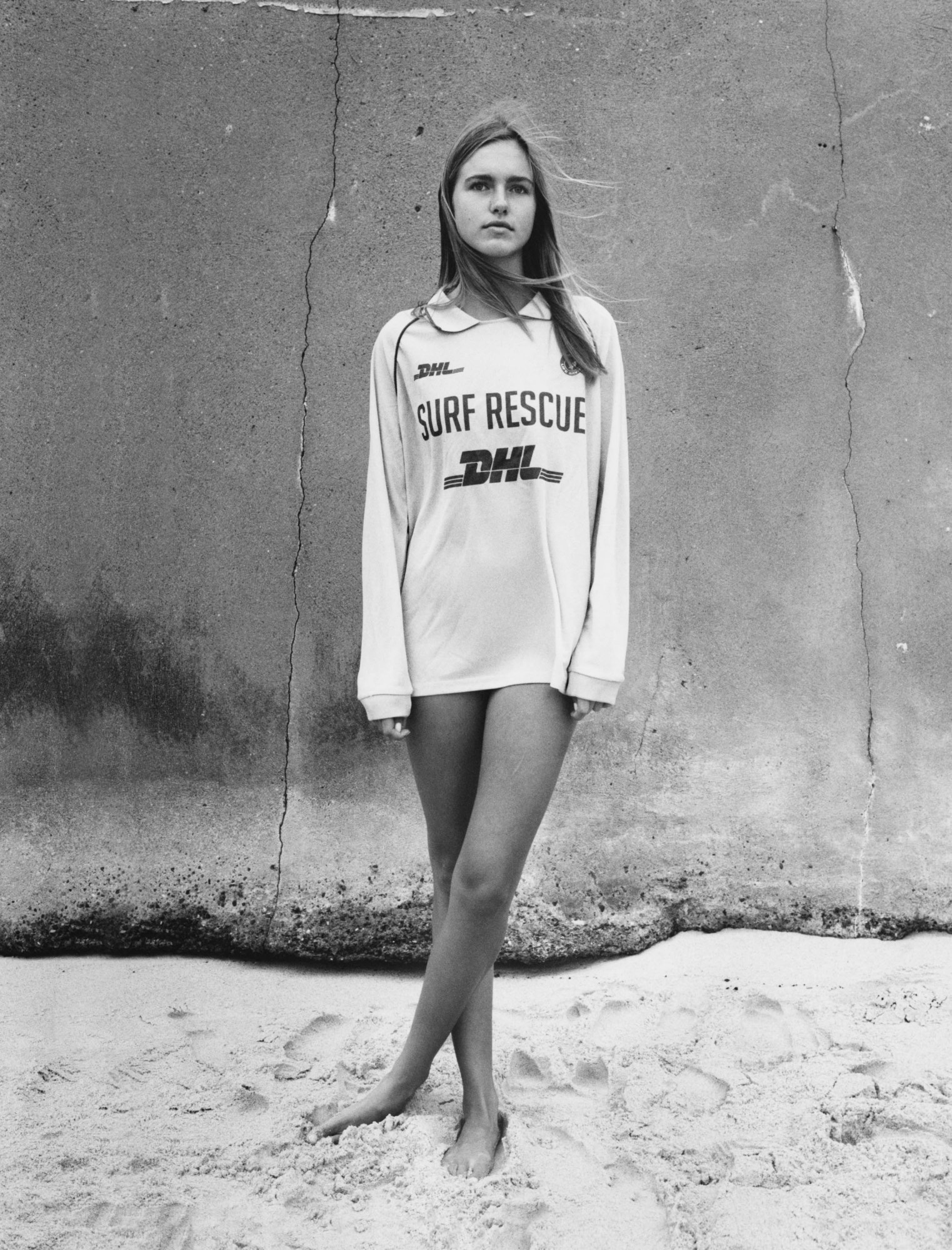

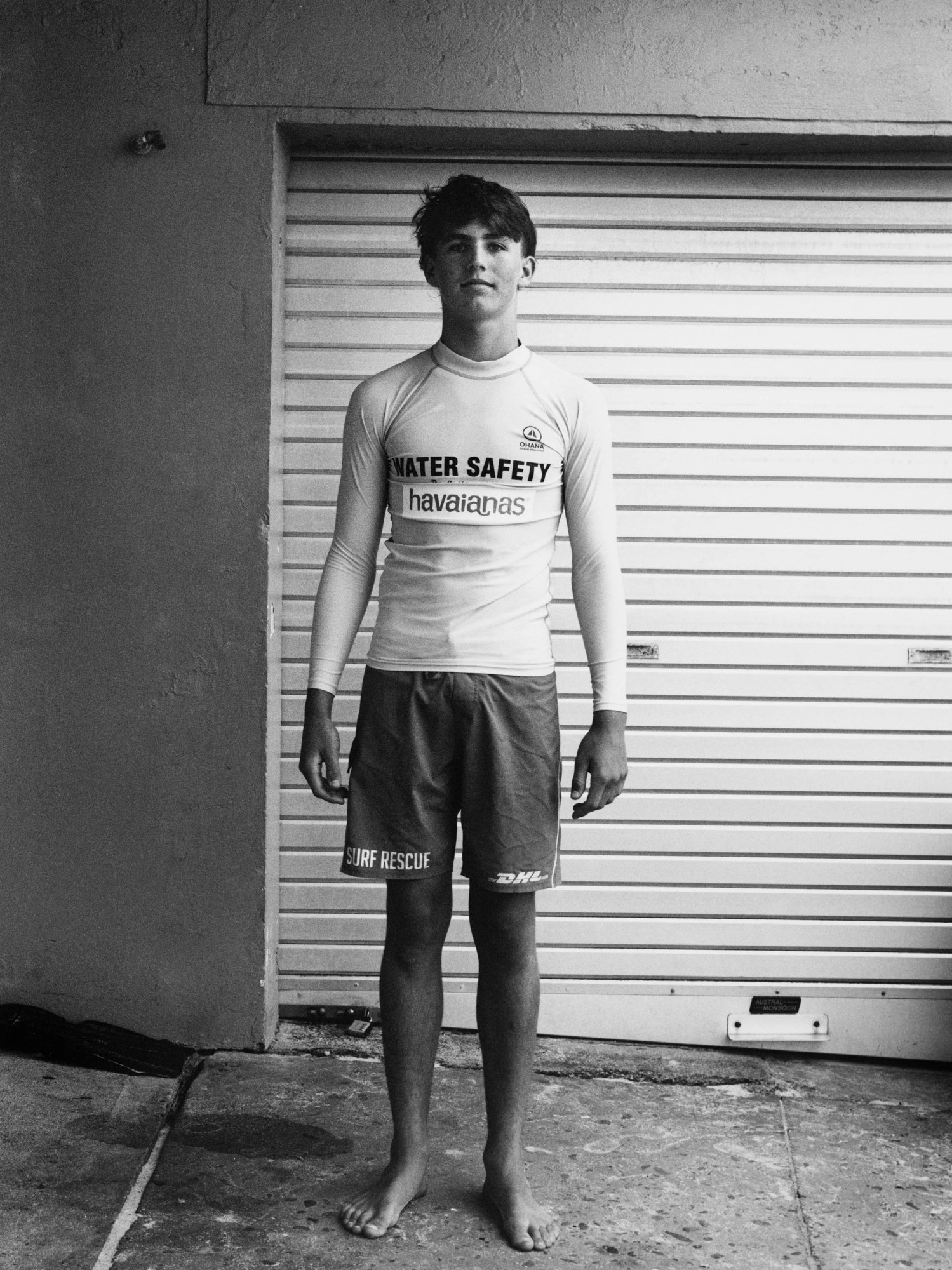

Real danger now feels like isolation, locking ourselves up in our boxes of gender, race, sexuality, nationality. Real danger feels like assuming we know someone’s story by looking at them; it feels like believing our pain is more important than anyone else’s. It feels like pretending human beings have borders, that we can win some game by flipping biased institutions. Because while we’re busy playing, we seem to forget these games were built by past generations, and they’re as old and destructive as the people who made them. We have a new challenge that doesn’t involve labels or boxes or ancient institutions, but is about global respect and a global consciousness. Being human alone binds us together, not lines we draw around ourselves. I think Australia’s youth is doing a wonderful job of horrifying their colonial ancestors. There’s a new recognition that the land is as much your family as the people who raised you. While I was taking pictures of one group of kids, mixed in with the usual teasing were shouts of encouragement, of genuine love that even a few years ago we were not taught to express so freely. There was talk of who was going to what protest, a sense of charged responsibility rather than inherited colonial shame.

It’s natural to want to cling to tradition in a vacuum of empty space, but an empty space is also openness. The new generation in Australia is free to fill that gap with Indigenous wisdom, a commitment to protect nature, and a charge of momentum against the old way. Of seeing and connecting on a human level.

This time going back home, I left feeling that being free from tradition might be something for us all to aspire to. That maybe it’s the perfect time to be a young Australian, to learn how to live with the land instead of buying into the illusion that nature exists separate from us, or that we exist separately from each other.

Credits

Photography Stef Mitchell

Production Reid Production.

Casting Gabrielle Lawrence at People File.

Special thanks Bronte SLSC and the National Centre of Indigenous Excellence.