Growing up in New York City’s fabled Chinatown during the 1950s and 60s, Baldwin Lee remembers playing on the streets with his friends with no adult supervision for hours until his mother opened a window and called him home for supper. But life was not picture perfect for the first-born son of Chinese immigrants, as Baldwin remembers cruel expectations to achieve placed upon him at an early age.

“There was no consideration for any kind of self-discovery on an individual basis,” Baldwin says. “As a very young child, my father told me I was going to MIT to become an engineer. I had no idea of what that was, but for reasons of fate and circumstance, I turned out to be a very good student. I went to Brooklyn Tech high school, graduated in 68, and was valedictorian — so my father was ecstatic. I fulfilled his legacy and got into MIT, but it was the worst thing ever. I had never suffered as miserably.”

Although Baldwin had achieved his father’s dreams, it has come at a high cost. He remembers waking at four in the morning to study for exams, reading and rereading the textbook so that many times that he could quote it verbatim during the test. “I mistook praise for affection, and it took me a long time before I realised I had not been treated as well as I could have been,” he says. “I was just fortunate to have been able to succeed in the terms laid down to me.”

Like many first-generation children, Baldwin was determined to follow the path laid out for him — but fate had other plans. During his sophomore year at MIT, he randomly signed up for a photography class taught by Minor White, a highly influential artist and educator who adopted a personal approach to image-making. From the moment Baldwin entered the class, he was absolutely stunned.

“Here was this man with a shock of white hair, [who] would conduct classes barefoot unlike other professors at MIY who were stodgy, rigid, and intimidating,” Baldwin says. “I didn’t know what to make of Minor White, but when he would speak, it was a revelation. He was a really spiritual person who believed in Eastern religion and mysticism. This was the 60s, and he would talk about [anthropologist and author] Carlos Castaneda. I had never heard anything like this, and I fell in love with him and with photography.”

Baldwin took Minor’s course, “The Creative Audience”, a wildly theatrical experience held in a dimly lit studio room. Students removed their shoes in the foyer and sat on the floor while Minor played Gregorian chant records, then put in the slide projector. His abstract black-and-white photographs would fill the screen, and students would gaze at them silently with the sole purpose of incorporating the images into themselves — visually, intellectually, and physically. The students then paired up to communicate what they saw through the act of touch. “What wild time!” Baldwin remembers of the group massages that took place. “I was converted.”

Baldwin switched his major to pursue photography, going on to earn a Bachelor of Science in Art and Design. “My father thought I was getting a degree in architecture. The moment of truth came at graduation,” he says. “On the ride back, I was sitting in the front seat next to him, and he asked me, ‘Now that you’ve graduated, what are you going to do?’ I told him that I wanted to do photography. There was a big silence. I looked over at him, and there was a tear coming down his cheek. My father was a reserved man, and the only emotion he displayed was anger and sometimes frustration, so to see him reveal a side of himself that I never knew existed was devastating.”

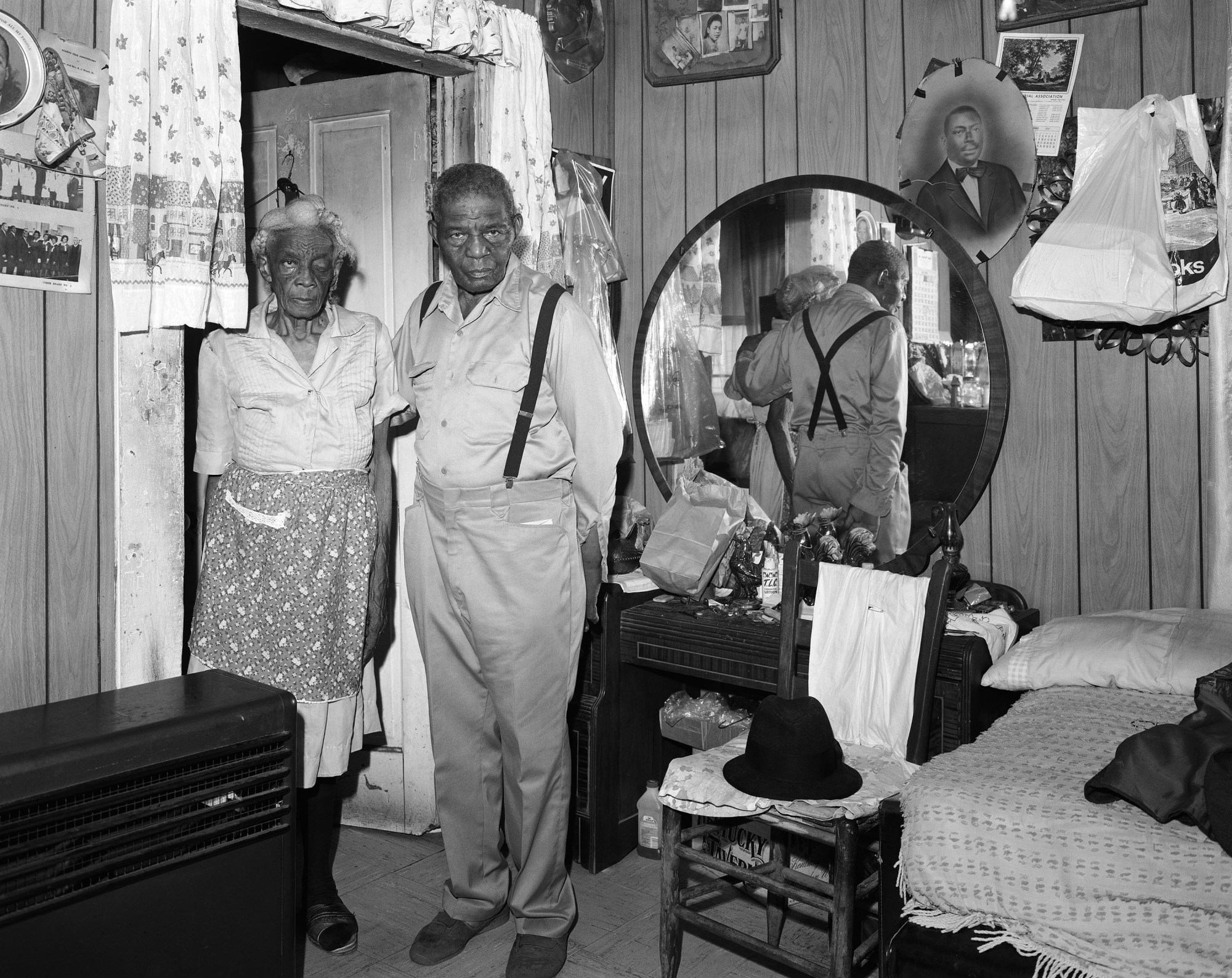

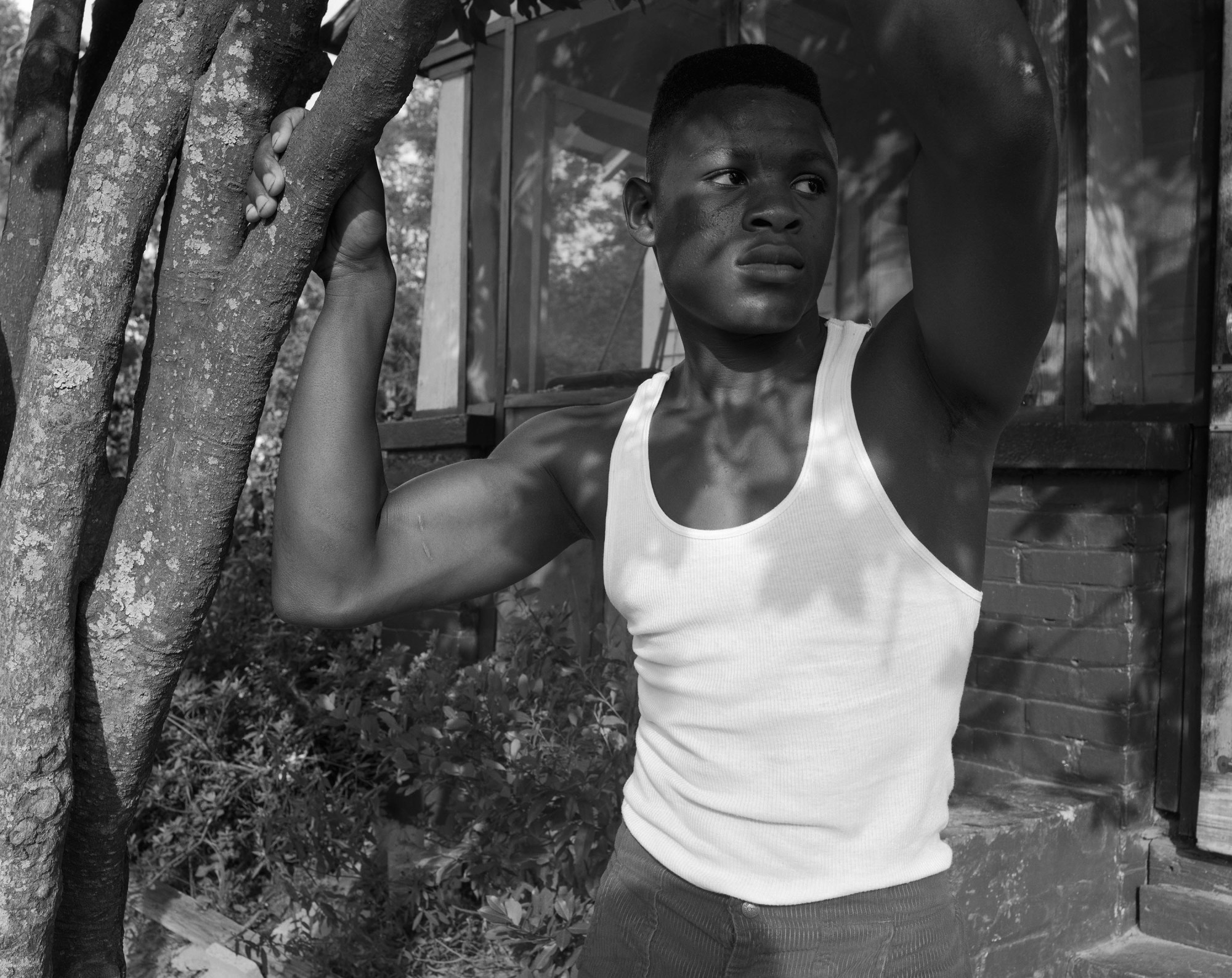

Tragically, Baldwin’s father passed six months later, and he never got to see his son achieve extraordinary success as a photographer. This month, Baldwin releases his magnum opus, Baldwin Lee (Hunters Point Press), a collection of portraits made while travelling through the American South during the 80s. Baldwin will also be exhibiting works from the series this fall at Howard Greenberg in New York and Joseph Bellows in La Jolla, California.

After his father passed, Baldwin took an integral step in his early career, enrolling in Yale to pursue his MFA with legendary photographer Walker Evans. As it so happened, Minor and Walker were virtual opposites in both character and work, providing Baldwin with the rational and mystical possibilities of photography itself. “Minor White was the embodiment of the counterculture, and Walker Evans was the opposite,” he says. “He was the first person I knew who was part of the American aristocracy. He was the most sophisticated, urbane man, and his writing was unparalleled. He was a dandy, dressed in tweed coats, English shoes, and he drank tea with milk. He was like somebody out of the Thin Man movies with William Powell and Myrna Loy.”

Baldwin regularly travelled between Cambridge and New Haven, sharing stories with his mentors about one another. “Minor considered [Walker] to be a pompous stuffed shirt and did not believe for a minute that he was the humanitarian the world thought because he didn’t buy any of the Let Us Now Praise Famous Men project [Walker] did with James Agee,” Baldwin says. “[Walker] thought Minor [was] the biggest BSer, although he didn’t use that term. He described him as you might describe a televangelist: that Minor White was just acting, portraying this person to develop a cult following. It was wonderful to go back and forth. And the thing is, neither one really taught photography.”

Looking back at his studies, Baldwin says, “I went to the best colleges in the country, and I emerged essentially uneducated. I didn’t know anything.” It wasn’t until 1982, when he took a position as a Professor of Art at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, that everything began to fall into place. To get the know the lay of the land, he set off on a ten-day, 2,000-mile road trip, visiting Louisiana, Florida, and Georgia, photographing everything he found interesting along the way. After processing the film, Baldwin realised what he loved most: his encounters with Black Americans he met along the way.

The following Spring, Baldwin embarked on what would become a seven-year journey crafting large-format collaborative portraits. He drove west through Nashville to Memphis, then south along the Mississippi River to Natchez with his camera and two books: August Sanders’ portraits and Walker Evans’ MoMA catalogue. Although Walker had photographed this same landscape half a century earlier, it looked very much the same despite the abolition of legal segregation. Baldwin stopped in front of a Greek Revival building in Natchez that Evans photographed in 1936, with a sharply cynical eye to chronicle the rise and fall of the Confederacy. Where Walker sought the classical symbols of Western culture, Baldwin looked to the people themselves — the people who became the human capital on which the United States was built.

As it so happened, Baldwin was very shy with strangers and remembers the stress of teaching his first class at Yale, his hands shaking and his voice stuttering before dismissing the class early and going to the department head’s office to resign. And though he wanted to quit, he did not give up. Instead, he pushed himself into the unknown.

“When I decided to photograph people [in the early 80s] I knew that I would be confronting a real devil in me, so I just forced myself,” he says. “I would go to places people congregated in the summer and walk up. It was agonising, and I was thrilled when somebody said yes. I didn’t care what the photograph looked like, and they were really terrible for a long time. It was discouraging to keep grinding out horribly unsuccessful things, but I was persistent to the point that I changed who I was. I made myself confident to the point where, when I arrived in the South, I was absolutely fearless.”

At 5’7″ and just 145 pounds, Baldwin’s lithe physique cast an unthreatening silhouette that matched his disposition. Open, approachable, and genuine, his sincerity and integrity earned him entrée into spaces where he was a stranger, oft-times the first Asian person many had met, carrying an old-fashioned view camera. With the camera on a tripod, Baldwin would set up the picture, asking the people he photographed to pose as he first saw them when they caught his eye. But no matter how much he directed the scene, the people would always improvise in a manner that came naturally to them, thereby taking the photograph to heights far beyond what Baldwin imagined.

“Since nobody I photographed was a trained actor, they would misinterpret or not be able to do what I wanted, and I loved that,” he says. “What I wanted would never be remotely as good as what they would do, and they didn’t even know they were doing it. I was just stunned, and that’s when I would push the cable release. It’s why people go to the theatre or look at figurative art. The piece is addressing something that you don’t know well but you hold dear.”

For seven years, Baldwin was possessed with a singular focus, one that he likens to Moby Dick. Ten thousand images later, he completed his work and knew the time had come to quit photography itself. Where many artists chase the dragon, seeking to reach the heights they once achieved, Baldwin knew when it was time to send his jersey up to the rafters rather than settle for less. In a culture that cannibalises itself, leaving at their peak confounds those who accept mediocrity in the hopes of achieving greatness again. But Baldwin stuck to his principles for reasons that go beyond the art itself.

One day in Augusta, Georgia, while walking down the street with his camera, a van circled the block and pulled over. A man asked if he was a photographer. Baldwin looked in the van and saw his wife, who looked distraught. He got in the van, and the drove him to a funeral home. Inside was a tiny coffin open, their baby lying inside. After taking photographs, the couple invited him back to their home for tea. “They pointed to their bed and told me this is where their baby died,” he says. “They didn’t have a crib. The baby was tossing and turning, got caught in the sheets, rolled to the edge of the mattress, and suffocated.”

Their loss hit Baldwin hard. He had just become a father and was wrapped up in a search for the perfect antique crib. Suddenly the distance between his life and the people he photographed was a bridge too far to cross. Emotionally and physically exhausted from the vision that had driven him to make this work, Baldwin knew the time had come to bow out.

“Rareness is intrinsic to greatness, and I think artists who continue to work past their period of peak creativity are lying to themselves,” he says, pointing to Walker Evans, who made his best work in 1935-6. “Between 1936 and 1975, when he died, Evans made a billion pictures, and none of them was any good. He died lonely, bitter, and disappointed,” Baldwin says. “I knew for myself I was not going to do that. Why would I want to make bad art?”

‘Baldwin Lee’ is on view from 22 September – 12 November 2022 at Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York and 22 October – 10 December 2022 at Joseph Bellows Gallery in La Jolla, CA. ‘Baldwin Lee‘ is published this month by Hunters Point Press.

Credits

Images courtesy of Baldwin Lee / Hunters Point Press