Black history and queer history, and the histories that meet at their shared intersection, have long been obscured from public view. Our narratives and contributions to culture have, through malice and bigotry, been rendered marginalised; as a result, LGBT History Month and Black History Month are moments for recentering, recalibrating and reckoning with the past, both as it was told and as we wish to tell it.

Only a prized few stories about Black, queer history cut through into the mainstream, but those that do are largely focused on the palatable: the neat, soft and shiny — if apocryphal. Even in the UK, these history months are dominated by this singular and distinctly American story: pastel infographics and viral tweets rehash the largely false account of Marsha P. Johnson as the Stonewall Riots’ brick-thrower du jour. Marsha and the brick is a platitudinous parable, far more interested in framing her as a ‘magical negro’ and messiah of queer liberation, rather than — as her friend, artist Jimmy Camicia, says — the kind of person who had rose stems haphazardly and defiantly sticking out of her hair. The kind of woman who sauntered out of a diner for an hour of hooking so she could pay the drug debts of a young, put-upon hustler, who no one else in the diner would even look at. The stories publicly traded now are all shallow hagiographies, not only masking, but contributing to, a deeper communal failure to meaningfully appraise our queer histories.

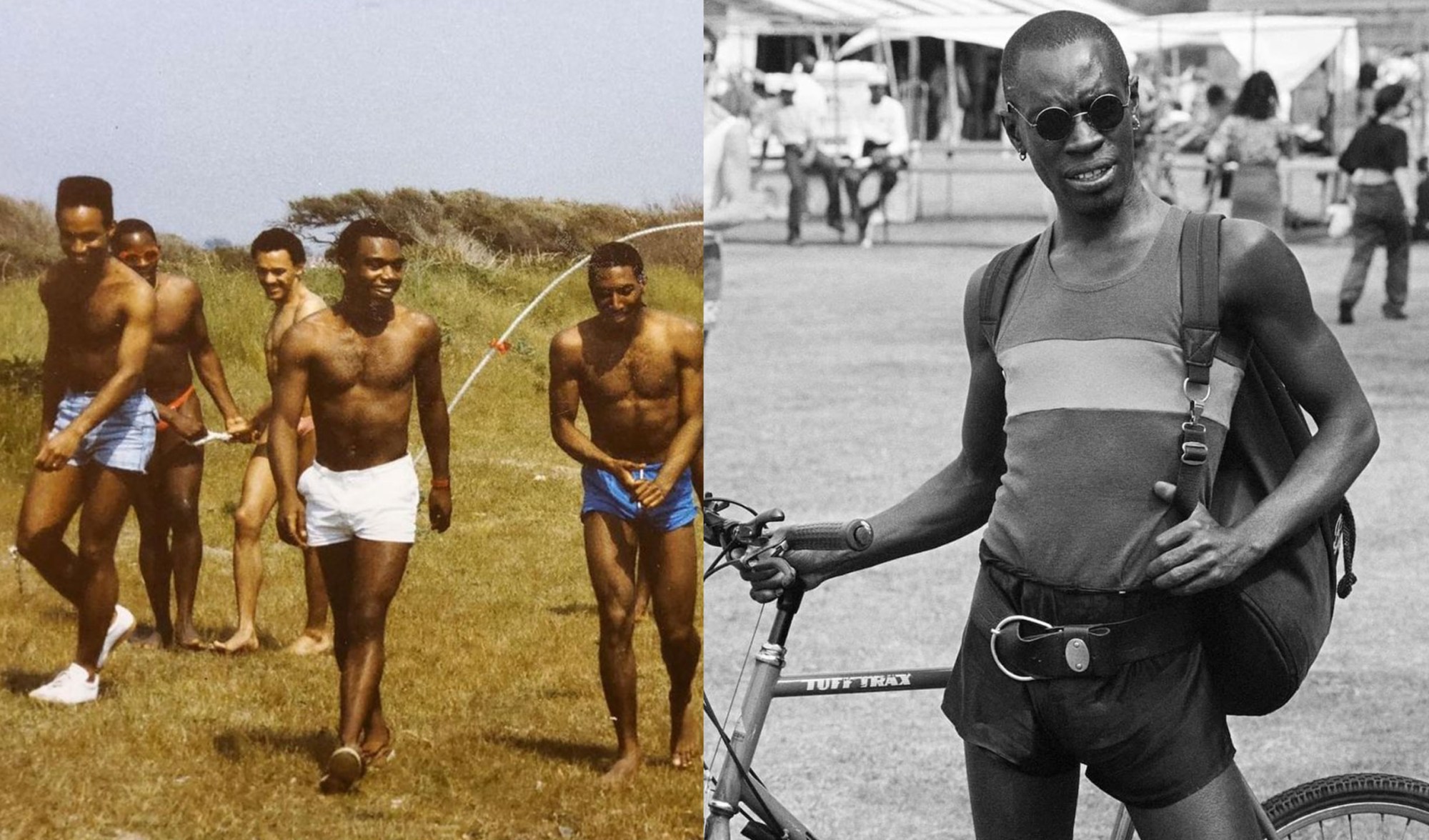

But standing out amongst the one dimensional and the played out, Black & Gay, Back in the Day is a new archive that uncovers more exciting, more edifying, and more realistic dimensions of our histories to explore. The Instagram project is on a mission to “honour and remember Black queer life in Britain, as it was.” It’s the curatorial brainchild of Marc Thompson, a decades-long activist and organiser, and Jason Okundaye, a writer, critic and devotee of Black gay memory work. The archive is an endeavour both driven by, and in celebration of, community. Marc recognises that conversations about our history are often dominated by so-called icons and iconography. With the archive, he hopes to change that.

“We need to remember the regular folk who built the foundation of our community,” Marc explains. “The archive is about demonstrating that we lived, and we live — the people featured might seem really ordinary, but they’re really special lives. So I wanted to show us partying, I wanted to show socialising, in union with each other as couples.” For Marc, it was important that the archive focused specifically on the stretch of time between the 1950s and the millennium, “to capture our experience, pre-internet and pre-digital,” he says. “Because after 2000, we got Web 2.0, camera phones, Black pride [started] in 2004 — the community is really different pre-2000.”

For him, the medium of Instagram, and partnering with Jason, were no-brainers. It was as much about the effectiveness of the project’s reach as it was about producing a meaningful intergenerational dialogue — one far from the nebulous bi-monthly Twitter proclamations about ‘lost gay elders’ that is so often substituted for the real and difficult work of bringing bubbled-off generations together.

“I’m always invested in the process as much as I am the output and the outcome,” Mark says, “so working with Jason, as a younger man half my age, is really important. The intergenerational process starts there. [The archive has experienced huge initial growth] not just because of his tech savviness, but his understanding of the way the platform works, and who to reach out to.”

Jason has always been drawn to this kind of cultural research and reappraisal, but memory work took on a primacy for him, after his father’s death, that it didn’t possess before. “The thing that comforted me the most was looking through old photographs of him, and hearing stories about when he first migrated to London, what he was getting up to, and hearing from his friends and his family and people who knew him,” Jason says. “Getting to understand that kind of lineage and ancestry and get a sense of what he was like, outside of being my father. That kind of made me realise that it is the photographs — it is the stories — that define life. My dad’s life wasn’t defined by his profession, it was defined by the friends he made, and the people he touched.”

Not long after his father passed, Jason watched Marlon Riggs’ seminal Black gay film, Tongues Untied. It got him thinking “about the amount of memory work that’s been done there, for the people who came after”.

“[Tongues Untied is an] archive of different behaviours that Black gay men exhibited,” he adds. “The gossip, and cattiness and snapping your fingers; but also the resistance, the dynamics and politics of relationships and love and rejection, and police brutality… all sorts of things.” His awe came with a realisation: why is no one doing this work for Black gay men in the UK? Later came the answer: to pursue this work publicly and with fervour.

Without this delicate and intentional work, preserving the dialogue between queer youth and elders, a wealth of knowledge — of joy and battles lost and won — is vanishing. A tendency for too-online cyberfags to speak of queer elders in noble and distancing terms, as an almost foundational sacrifice, erases their continued presence in our communities now. Ostracised, they have an eagerness to break bread and share stories with us.

“I hope it encourages us to reach out across these lines,’” Marc begins, “[so young] people who view this on Instagram dig deep, start to ask questions, reach out to elders and say: ‘Look, tell me some more. That’s an amazing thing that happened’. I also hope it reconnects some of our elders. I’ve seen some posts already on Instagram with somebody in the comments saying, ‘That’s my girlfriend!’

“Particularly in these COVID times, it’s a beautiful reminder of what we’re missing: that unity, that sense of connection and community. It’s a reminder that we don’t have that right now. But we will have that again.”

Remembrance is an act of love, and Black & Gay, Back In The Day is a labour of it in the truest sense. There is a blueprint to the trials we face now, solution to schisms and an irreplaceable oral memory to be handed down, if we act, quickly and with purpose, to preserve it. There is much to learn and love if we seek it out. We dust off, we make new.

Follow Black & Gay, Back In The Day on Instagram here, and follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more queer stories.