Public interest — and the market in — contemporary Black American art have boomed over the past two decades. But it still comes as something of a surprise to learn that the first major museum survey of work by Black American artists took place 45 years ago. The honour goes to Two Centuries of Black American Art. Curated by the late David Driskell, a painter and then the head of the art department at Fisk University, the exhibition opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on September 30 1976, travelling to Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, and, finally, New York‘s Brooklyn Museum. While it was not the first museum show to explore the till-then relatively unexcavated field of Black American Art, it was the first to do so with such rigour — comprising over 200 works, it testified to an artistic tradition long omitted from the American art canon.

It was “an inflection point in the institutionalisation of African American art,” says Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the literary critic, Harvard professor and executive producer of Black Art: In the Absence of Light, a new HBO documentary that traces the legacy of both the exhibition and its curator, from the day of its opening to the present day.

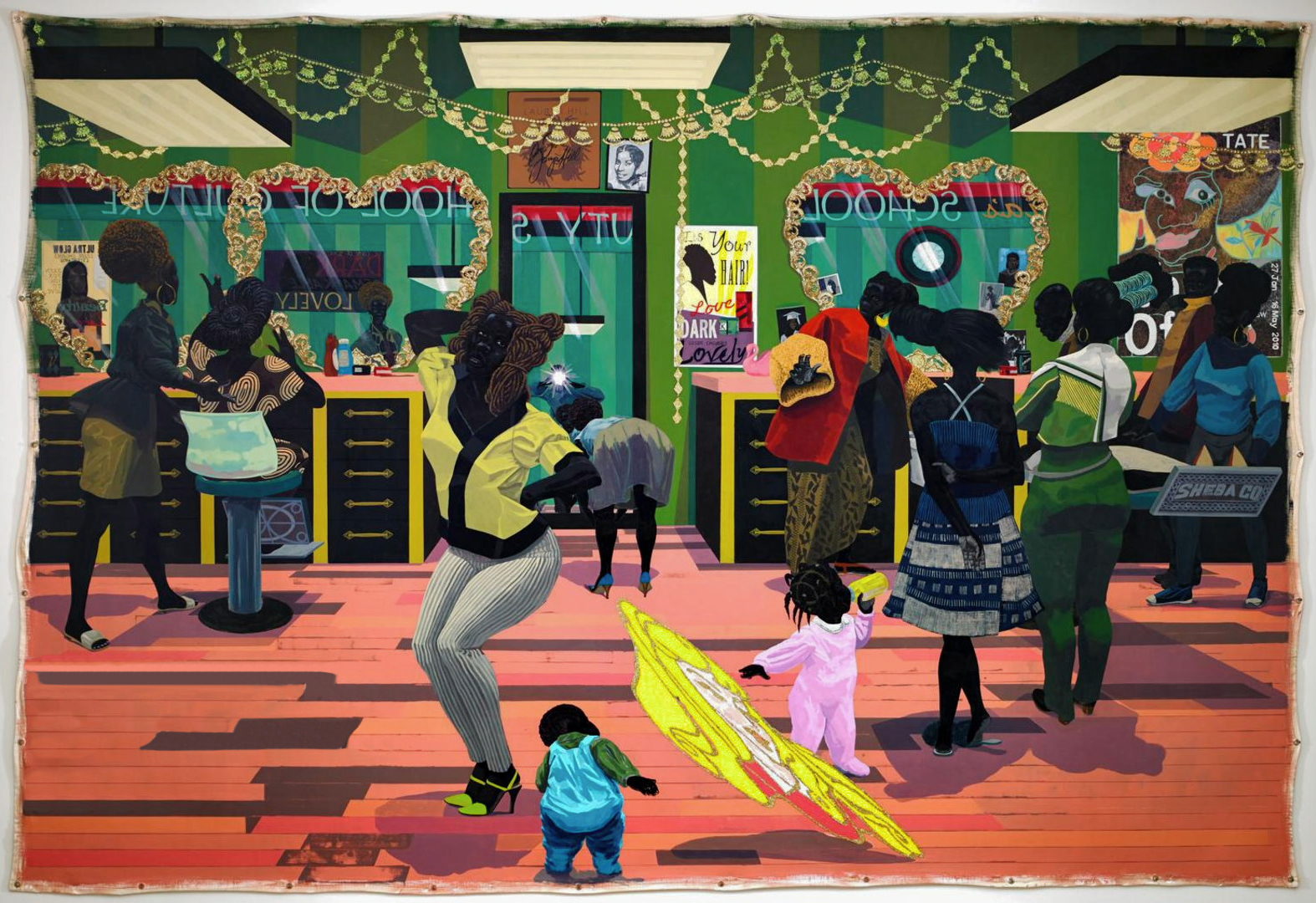

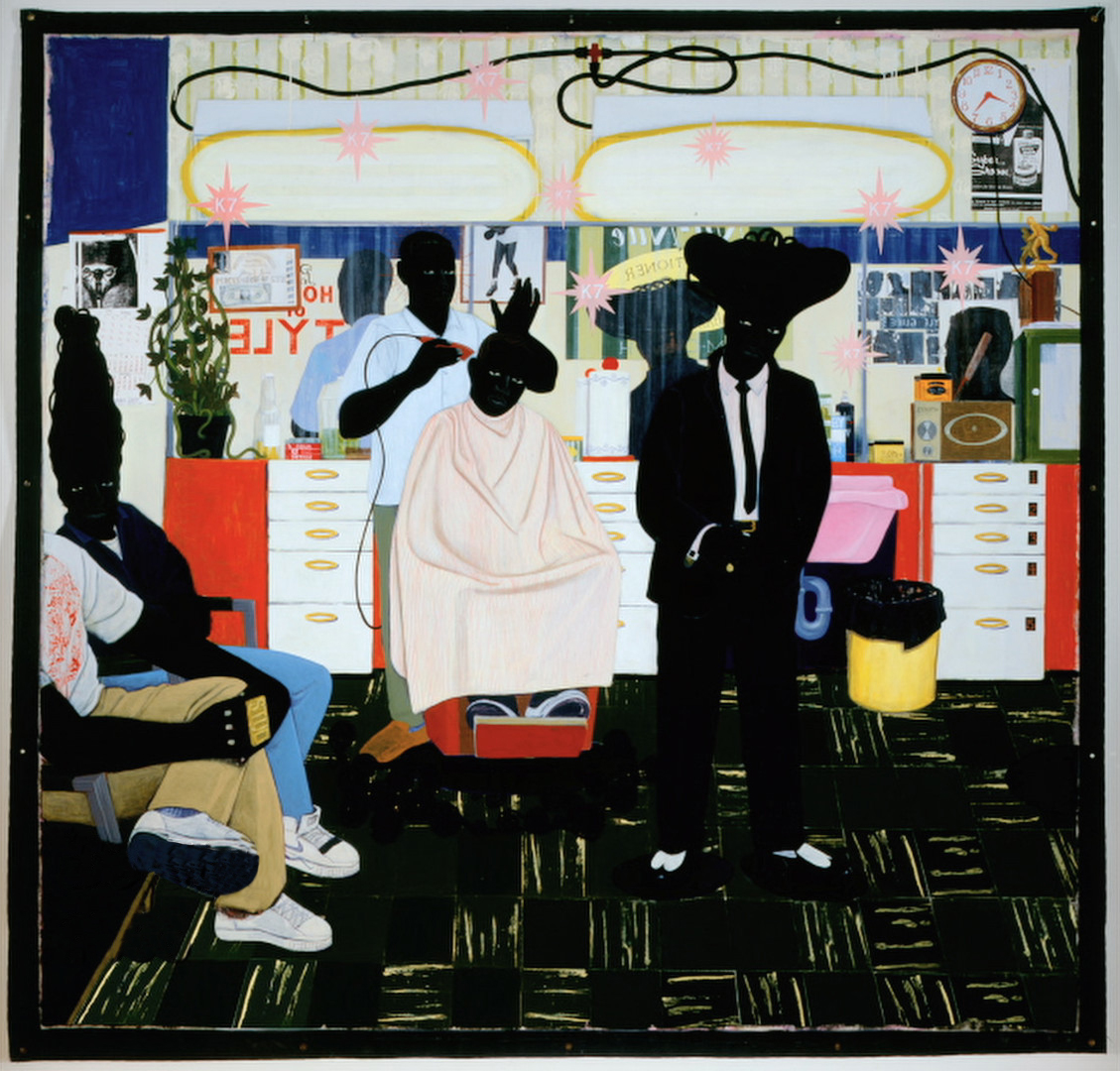

In many respects, the project at the heart of the feature-length film — directed by esteemed documentarian Sam Pollard — is similar to Two Centuries…’. It offers a genealogical sketch of Black American art since the exhibition, charting the intergenerational relationships and influences that pushed things along to where we are now. We learn, for example, of the impression left on a young Kerry James Marshall by the silhouetted figure in Betye Saar’s Black Girl’s Window (1969). Seeing the painting set him on the path to discovering the nuanced shade of black that colour the figures in his rich tableaux today. And while Jordan Casteel may not have even been born at the time of the exhibition’s run, she recalls how leafing through the pages of the exhibition’s accompanying book as a child offered her “a sense of belonging”, an understanding of the foundation that “my community of Black American artists that come before me have created […] for me to build on,” she says.

More than simply spotlight individual artists and how they’ve carried Driskell’s legacy forward, due focus is placed on the landmark moments and locations that speak to the development of Black American art as an institution in its own right. One such example is Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, the Whitney Museum‘s 1994 exhibition. Curated by Thelma Golden, it brought together the works that dealt with Black masculinity as their explicit subject, irrespective of the artists’ racial or gender identities. For the first time in a major American art museum, “you were seeing Black masculinity not as something on television that’s menacing or [to be kept] at arm’s length, but rather artists embracing it as the subject matter, and as the colour on their palette,” Kehinde Wiley says. “It was mind-blowing, an exhibition that really tore down the meaning of the Black body itself.”

Another pertinent example is, of course, the Studio Museum in Harlem, a proud protector of the legacy of African American Art, of which Golden is the current director.

That Black Art: In the Absence of Light venerates the history of Black American artistic expression is a given, but it adopts a welcome polemical stance regarding why art history should be considered in such, well, black and white terms. It’s a question made all the more interesting by Thelma Golden’s involvement in the film as a consulting producer. It was her, after all, who coined the term ‘post-Blackness’, which she used to describe the work of artists “adamant about not being labelled ‘black’ artists, though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of blackness” in an essay printed in the catalogue for Freestyle, a show she curated at the Studio Museum in 2001.

It’s a sentiment widely felt among Black creatives today and is the product of a dense combination of antagonising factors. A stand-out among them is the historical tendency of institutional agents — from critics to museum directors — to treat Blackness as a monolith, packaging an ineffably complex entanglement of experiences and histories into “neat boxes that feel tangible to the masses,” Jordan Casteel says.

“Teaching a critic or curator to perceive a work of art outside of this ghettoised category of just Blackness is the mandate for our generation, it seems to me,” Henry Louis Gates, Jr. concurs. His statement, however, does not weaken the case for the elaboration of an art history that investigates and celebrates the unplundered depths of Black contributions to American art. In fact, it reinforces it. At its heart, Black Art: In the Absence of Light is a testament to both the “expansive possibility in cultural specificity”, as Golden puts it, as well as to the need for a critical approach that views work by Black cultural producers as more than an expression of its makers’ race.

It would be crude to reduce the film, and by extension its dense subject matter, to a single point. Perhaps the most powerful achievement of Black Art: In the Absence of Light, though, is its unflinching presentation of an incontestable truth — that Black American art and art history are cornerstones of American culture, and keys to fully understanding the nation’s troubled history. “It is impossible to understand the history of the United States without understanding Black artistic expression. For some time and for all time, that arts have been the main avenue through which to declare, to imagine, to critique, to respond to the conditions of life and our hope for a better one,” says Sarah Lewis, Associate Professor of History of Art at Harvard University. “Whether you appreciate art or not, it doesn’t matter. If you want to know anything about the power of the human spirit to exist despite difficult circumstances, you have to start to learn about Black art.”

Watch Black Art: In the Absence of Light here, and follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more art.