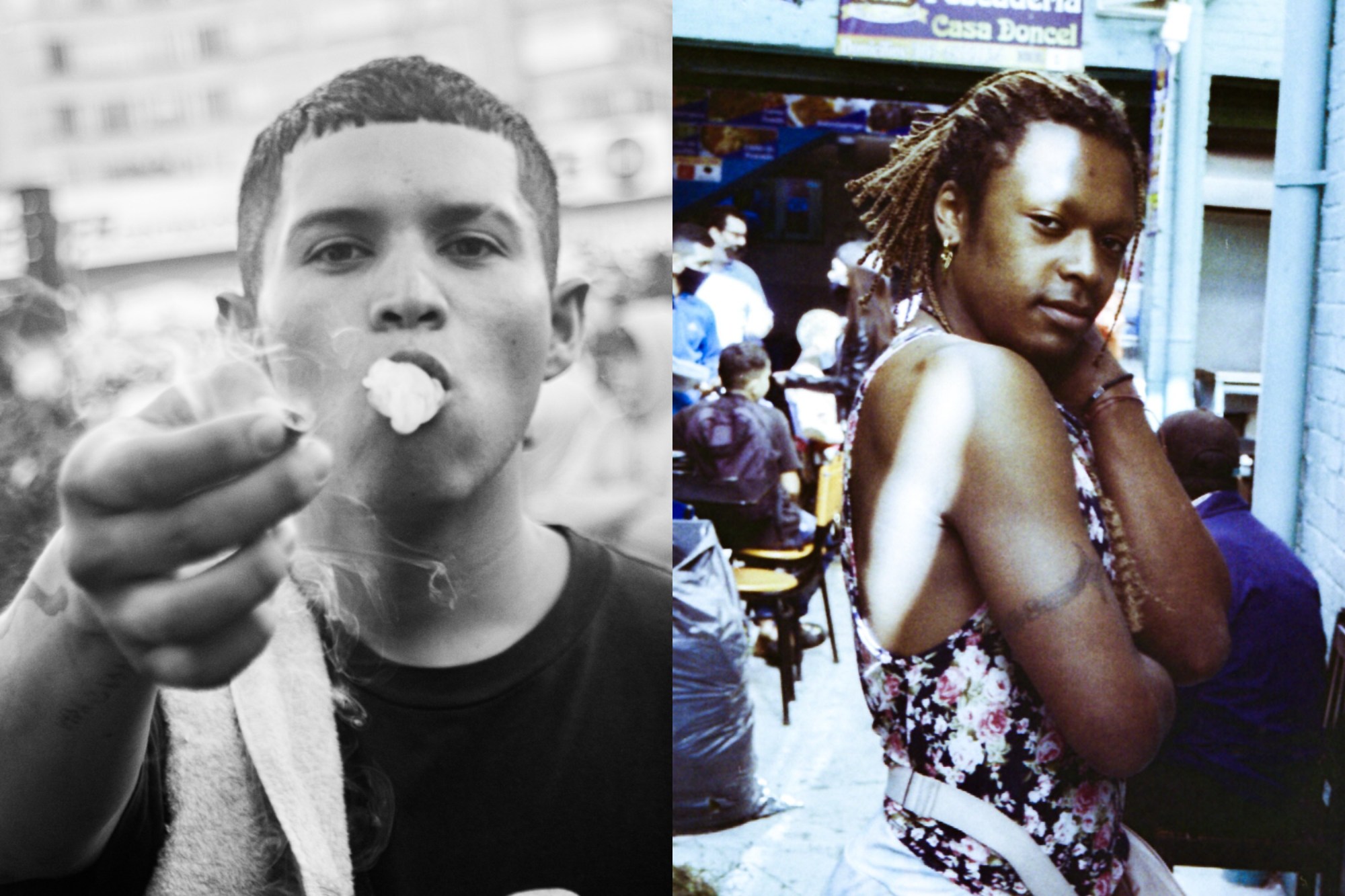

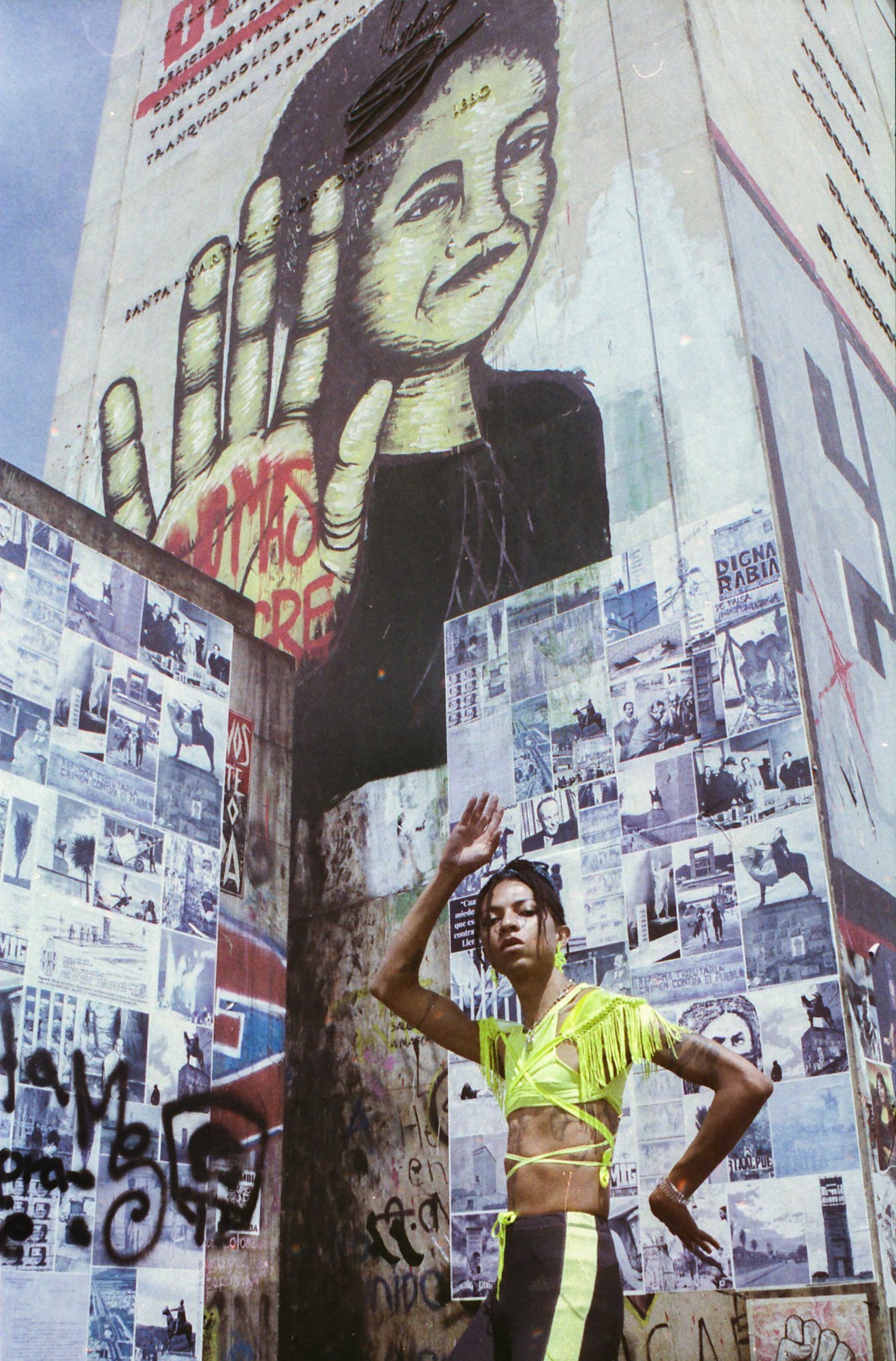

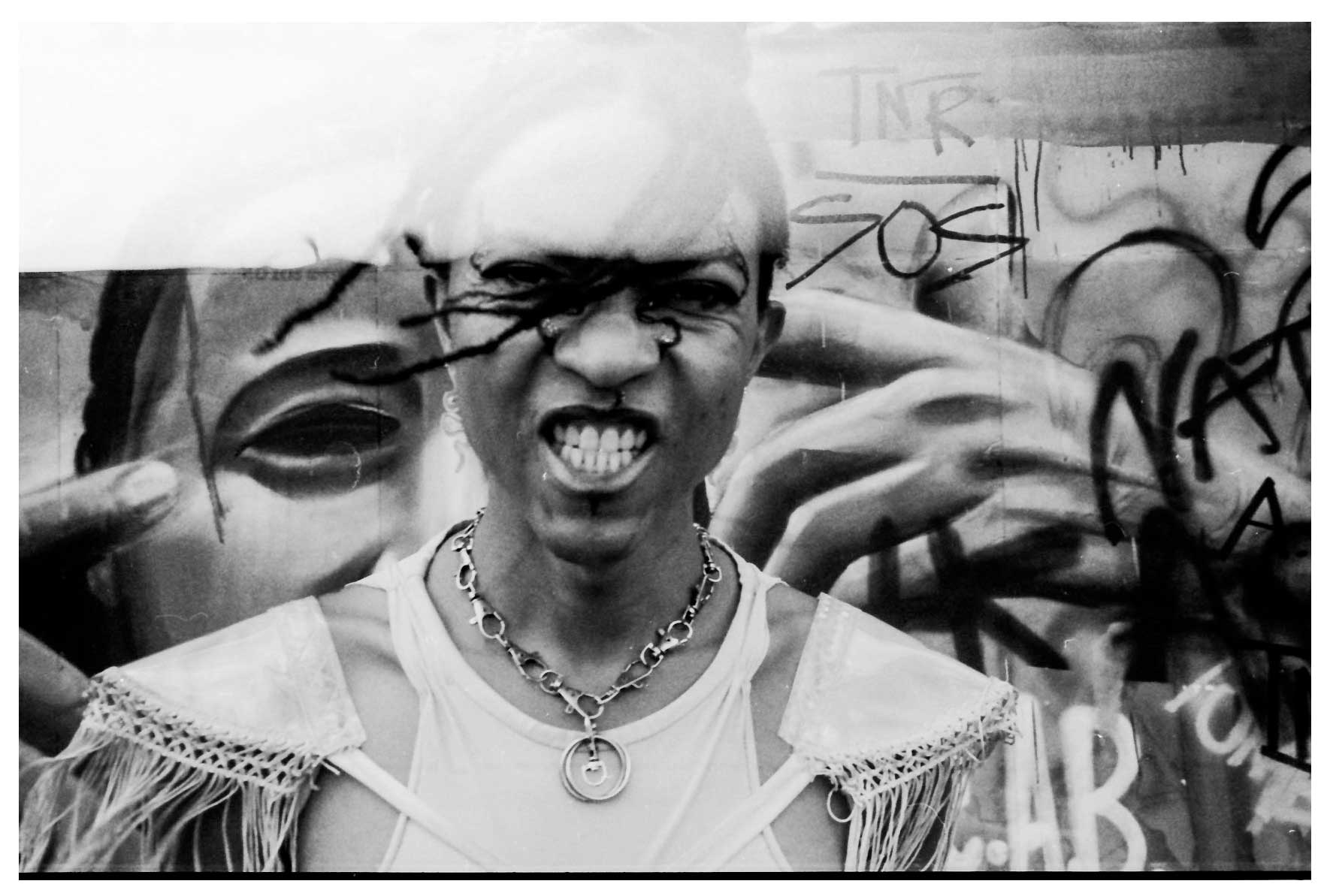

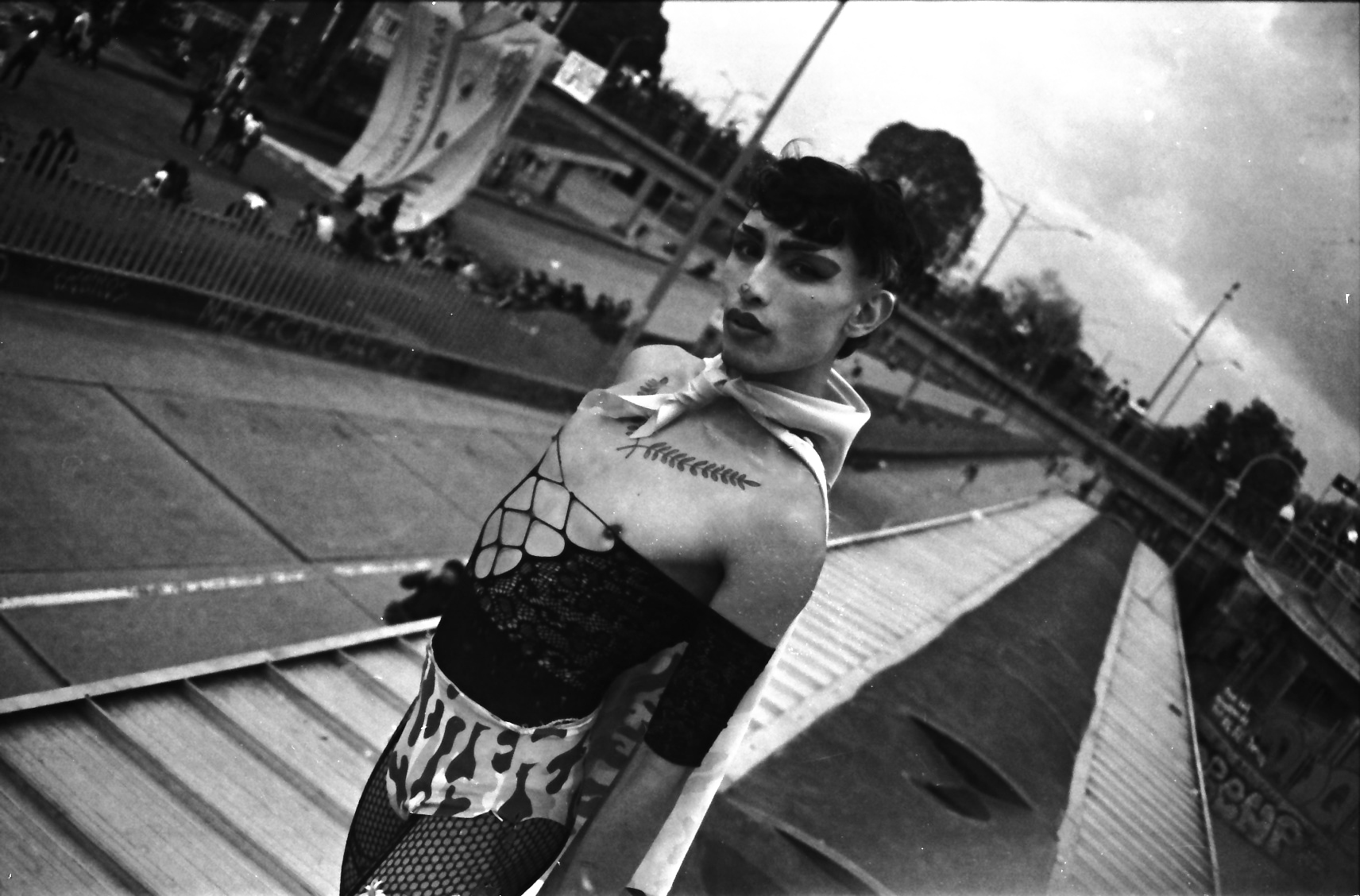

On April 28, TerCas collective member and Afro-Colombian trans organiser Pantera Godoy twerked on a police shield during a protest in Bogotá. The iconoclastic moment — as well as the widely-reported action on the same day in the city’s Plaza Bolivar by fellow vogue dancers-slash-protestors Piisciis, Nova and Axid — went viral on social media. A subsequent shot of Pantera voguing down at Los Hippies Park a few days after that landed on TIME, further bolstering their cause. “We finally have a lot of eyes on these issues abroad, not just as trans and queer issues but as Colombian issues,” Pantera says over WhatsApp. “The revolution and the internal uproar we’re causing has really become visible.”

The recent wave of civil unrest in Colombia is an amalgam of several collectives banding together and organising en masse against the government in a movement known as El Paro Nacional, or “The National Halt.” A massive decentralized movement including Comité Nacional del Paro — which brings together Colombia’s Central Union of Workers, Cruzada Camionera and Central General de Trabajadores — as well as Indigenous groups like La Minga, students, civilians and other activist groups — El Paro has been raging since April 2021. Years of dismay with the current government finally boiled over when President Iván Duque attempted to implement a tax on citizens to counteract economic loss from the pandemic, despite 37.5% of the population falling below the poverty line by the end of 2020. The tax plan was defeated, but El Paro continues.

The ongoing protests brought other longtime issues to the surface, including racist policies, poverty and migration. Amidst these protests — which have seen 75 civilian deaths, 89 disappearances and countless injured or arrested according to Colombian media group La Silla Vacía — queer collectives like TerCas (an acronym for “territorio cuir assumido”, or “reclaimed queer territory”) have risen up. Queer and trans-led activist groups — such as El Frente de Resistencia Trans-Feminista Marikón, Toloposungo and Contra-Marcha — have also been on the front lines of the protests advocating for the same issues integral to the larger movement, while highlighting those specific to the queer community in Colombia.

“In some ways, us hitting the streets has made waves among sexual and gender dissident communities,” says Citrina of Toloposungo (short for “All Police Are A Gonorrhoea”). “They feel empowered by who they are and feel they can fight and break homophobic and transphobic ideologies. Parts of Colombia outside the capital still reject us, and that large-scale rejection comes with large-scale violence.”

According to queer human rights organisation Colombia Diversa, over 60 queer and intersex individuals were killed in the first eight months of 2020 alone, and LGBTQ+ people have suffered from historic rates of police brutality, threats and violence. It’s an unfortunately all-too-common statistic worldwide, and a harrowing one in South America where Colombia is second only to Brazil as the most dangerous country on the continent for queer people.

In a climate of state-sanctioned violence against queer and trans bodies, workers and artists within the community started organising their own support networks. Amongst members of Bogotá’s flourishing underground ballroom scene — thanks to voguing collectives like House of Tupamaras and House of Yeguazas — conversations about mutual aid and community protection for and by the trans and queer community have been kickstarted. Groups like El Frente have been out on the streets since early May marching in support of the Paro Nacional and the queer community in Colombia at large, staging protests in smaller provinces outside of Bogotá to show solidarity for queer people outside the capital who may not have proper support networks.

“El Frente was born as a space of action, organising, and liberation for queer and dissident bodies,” says Demonia Yeguaza, a prominent member of the collective and house mother of The Yeguazas. “We want to have representation in the streets and in places of political influence where we can make decisions for our community and legitimise them through rule of law. El Frente has supported the Paro Nacional since its outset. I know that from all the different angles we’re coming from — all the different collectives and movements — we’ll be able to achieve something important that will give our community an opportunity in the future. I feel a collective rage, a desire to fight to re-dignify our lives, our rights, our spaces. We already know how to find resources, put on events, achieve big things… the future is not depending on an institution or a system and having autonomy within our own communities.”

Colombia has made strides of progress with LGBTQ+ rights when compared to the rest of South America. The country has passed a slew of progressive laws and reforms in recent years — becoming the fourth country in South America to legalise same-sex marriage — and has elected several queer-identifying officials into office, including Bogotá’s mayor Claudia López. All this said, there’s a glaring paradox as far as Colombia practicing what it preaches; although law suggests that there’s a safeguarding of vulnerable LGBTQ+ people in the country, it’s rarely enforced, leaving queer and trans people vulnerable. This is something on-the-ground organisers know too well.

“There’s always resistance and it’s weird,” says Pantera. “We’re out here marching for equal rights, health, education and everything, but when you hit the streets protesting as a queer or trans or dissident body, most people will still resist your presence. This doesn’t always happen; a lot of people end up joining our marches when we show up as a unit with groups like El Frente, Toloposungo, la Contramarcha and la Primera Línea Maricona. I love that there’s so many of us. What can escape one collective as far as struggle and highlighting specific issues, another collective can pick up the slack and amplify that issue. I’ve personally been calling on all of us to link our theoretical ties into public politics. Who knows if in the future we could see a queer political party in Colombia?”

The struggle for queer and trans rights and organisation in Colombia often intersects with the struggle for Black lives and the global call for police abolition. Afro-Colombians have been protesting racist policies and disproportionate killings of Black Colombians by police for years in largely Black cities outside Bogotá, such as Cali or the port city of Buenaventura. Calls to abolish the police were exacerbated with Black Lives Matter becoming a global movement and the killing of Javier Ordoñez by the police through excessive use of force last October.

“Bogotá is a largely white city, and even in anti-establishment and queer collectives we see recurring situations with white queers and cultural appropriation,” says LoMaasBello, a queer trap musician and member of Toloposungo from Buenaventura, who at the time of our interview was prepping for a protest on July 16 called Yo Marcho Trans (“I March Trans”). “Another Black girl and myself proposed that we examine what colonial practices are still present in our collective that have been normalised in Colombia, which is a super racist country. We need to have these discussions within activist spaces, because at the end of the day nothing can safeguard us from continuing to promulgate a colonial mentality through certain attitudes. It makes me wonder — as a person who is trans, Black and a migrant — where my place is in this struggle.”

Black trans women in Bogotá’s activist spaces fight double: against a conservative government that suppresses queer and trans bodies, and against the colonial roots of racism against Black and Indigenous individuals. It’s a struggle with a long way to go, one that comes with a demand not just to allow Black trans organisers to take up space and more actively shape the discussion, but to have their humanity and transness respected in a bigger context.

“I have a problem with the question of acceptance,” Pantera says. “Personally, and I’ve lived this and heard it from a lot of the other girls, we don’t want to be accepted — we want to be respected. I don’t make community aid groups to be ‘accepted’ and for others to try and coexist alongside me within their norms. I’m out here demanding respect, a respect that I have for any person regardless of sexual orientation, religion or any belief different from mine.”

Within Colombia’s struggle against inequality, rising poverty and police violence, progressive youth and people of all ages must turn to their queer comrades for guidance as they carve a better future for Colombia. Queer and trans organizers in Bogotá continue to put themselves on the frontlines not just for their country, but for visibility, liberation and autonomy within their communities. It’s essential these organizers and their work be amplified in the larger framework of El Paro, so the queer community is not left behind as the country continues to push for change.

“There’s a saying here in Colombia: ‘If care is what you care about, take care of it yourself,’” LoMaasBello says. “And who else knows the needs and dynamics of a community other than the people in it?”

Credits

Photography Frank Sanchez.

Quotes have been condensed and translated from Spanish. Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more activism and culture.